A Race To Save Florida’s Manatees

17:32 minutes

Florida’s waterways are home to a charismatic mammal: the manatee. These gentle giants are sometimes called “sea cows” for the way they graze on seagrass, the long, green plants that grow underwater in their habitat.

But in Florida’s Indian River Lagoon, the seagrass is disappearing fast due to algae, which is caused by pollution in the water. This loss of food has put the manatees in great peril. Last year, over 1,000 of them died—more than any year on record.

While threats to manatees are not new, this accelerated die-off concerns scientists, and is prompting a search for novel ways to help the Sunshine State’s sea cows. Joining guest host Miles O’Brien to talk about manatee conservation in Florida are Patrick Rose, executive director of Save the Manatees Club in Maitland, Florida, and Cynthia Stringfield, senior vice president of animal health, conservation and education at ZooTampa in Tampa, Florida.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Patrick Rose is the Executive Director of the Save the Manatees Club in Maitland, Florida.

Cynthia Stringfield is Senior Vice President of Animal Health, Conservation and Education at ZooTampa in Tampa, Florida.

MILES O’BRIEN: This is Science Friday. I’m Miles O’Brien. Florida’s waterways are home to a charismatic mammal, the manatee. These gentle giants are sometimes called sea cows for the way they graze on seagrass, long green plants that grow underwater.

But in Florida’s Indian River Lagoon, the seagrass is disappearing fast. Algae caused by pollution is to blame. And this loss of food has put the manatees in great peril. Last year more than 1,000 of them died, more than any other year on record.

Today, we talked to two people who are deep in the world of manatee conservation in Florida to find out why this is happening and what can be done to reverse this loss. Joining me today are my guests Patrick Rose, executive director of the Save the Manatee Club in Maitland, Florida, and Cynthia Stringfield, senior vice president of animal health, conservation, and education at Zoo Tampa in Tampa, Florida. Welcome both of you to Science Friday.

PATRICK ROSE: Great to be here.

CYNTHIA STRINGFIELD: Thank you for having me.

MILES O’BRIEN: All right, Pat. You go back to the beginning when it comes to the effort to save manatees, back really in the late ’70s. Give us a short history of your experience with these animals and the efforts to save them.

PATRICK ROSE: Well, I literally moved to Florida to work and save manatees in 1976. And I had been a diver, underwater photographer, for years before that. Finishing graduate school, we packed up everything– and I would like to relate the first part of a manatee I saw underwater was a scar. And it was a scar from a boat propeller. And that stuck with me my entire life in terms of what needed to happen.

These were defenseless marine mammals. They can reach more than 10 feet in length, over 3,000 pounds, although that’s large on average. But they really are defenseless. They’re not capable of aggression, and they’re a vegetarian.

And that’s the main problem we’re having at this moment in time, with hundreds of them dying, because man polluted the Indian River Lagoon so much with the nitrogen from our waste waters. And it’s produced algal blooms that shaded out the sea grass and killed it. And so we have them literally dying by the hundreds.

MILES O’BRIEN: So when you first got involved, there were on the order of 1,000 or less manatees. One of the big problems at the time was the boat strikes, the propeller strikes. And you literally put the manatees into public consciousness and on the license plates and helped turn things around in a very significant way. So the manatee population today is bigger, and you were actually, not too long ago, thinking about retiring, right? Because you had succeeded.

PATRICK ROSE: Well, I’ve had more than 45 years professional work in it. And we had over several decades actually helped improve the population through major recovery efforts. And we were gaining ground, you know, right and left, so to say.

But about a decade ago, we started seeing these problems increasing. But still, we were managing, and we had developed a good network of researchers. The Manatee Rescue and Rehabilitation Partnership was coming on strong. But we really did not believe that it could get so bad in the Indian River Lagoon that we would see starvation being a problem for manatees.

MILES O’BRIEN: No retirement for you yet. We’ll talk a little bit more about how we can fix this problem in a minute. But Cynthia, let’s put manatees in their ecosystem. What is the role they play in the environment?

CYNTHIA STRINGFIELD: Well, that’s a great question. So as Pat was saying, they’re unlike most other marine mammals in that they’re herbivores. So they eat plant material. I think most people are used to whales and dolphins and sea lions, and they eat fish, and so they’re carnivores out there keeping that population in check. These guys are keeping the greens in the environment in check. So as things are growing in the water, they’re coming along and munching on them.

MILES O’BRIEN: Well, Pat, you mentioned those algal blooms. And you know, I think we can guess what the causes might be. Why don’t you run through it, though? And that would potentially get us to some ideas on how this might get turned around? But frankly, it’s not as easy as telling people to slow down their boats, is it?

PATRICK ROSE: No, not at all. In fact, the three main factors that give that extra nutrient or pollution to the environment come from leaking septic tanks and drain fields that work their way into the groundwater and into the bay. You have runoff from the uplands that include the fertilizers, whether it’s from residential, from the lawns, or from the agricultural side of it. And then human waste. Even when you have the sewage treatment, it’s not being treated to advanced wastewater levels.

Those are combining, and it’s come over decades of time. So we built up too much nutrient in the environment, and then basically, the phytoplankton blooms in such billions and trillions, it gets so thick, that it cuts off the light to the seagrasses, and the seagrasses die. And then those nutrients became available, and it repeats that cycle, with one bloom after another over the years.

One thing I’ll add about the manatees– they’re kind of like nature’s gardener, as Cynthia has talked about. And they co-evolved with the seagrass communities over millions of years. And so for those people that might think, well, the manatees are eating it and that’s the problem, that’s not it at all. When the manatees graze and move around naturally, they actually stimulate the regrowth, and you have a higher productivity within those seagrass communities.

MILES O’BRIEN: Now, the Indian River Lagoon stretches from Cape Canaveral all the way down through Fort Pierce. It’s a big body of water, very shallow, doesn’t have a lot of flow back and forth. And there’s a lot of septic fields alongside it, golf courses, you name it. Is it something, with that many people living around it, that can be cleaned up in a reasonable way?

PATRICK ROSE: Well, the answer is yes. But it is going to take– it’s going to take foresight, it’s going to take money, and it’s going to take commitment. Florida has been growing unsustainably. We have not been treating our wastewater to a standard that really what it should be is like drinking water. And we’ve been mortgaging our future by development actions, and putting houses and septic systems where they didn’t belong, where they leach into the groundwater.

And in mortgaging that solution, I think right now Mother Nature is about ready to foreclose on Florida, along the east coast in particular, because we have so much excess waste going into that. And we’re going to have to invest the billions of dollars it’s going to take to turn that around. And we hope that that would be a part of even the efforts in Congress right now, because what’s more basic to infrastructure than how we deal with our own human waste?

MILES O’BRIEN: I don’t think you’re going to be retiring very soon, Pat, solving that one. Cynthia, tell me a little bit about why this comes to attention when it’s colder.

CYNTHIA STRINGFIELD: Yeah, manatees face multiple problems out there. And recently, the UME, or the mortality event that we’ve been talking about on the east coast has gotten a lot of attention, which it should. But there’s also a lot of other things that are still going on out there. We talked a little bit about them being hit by boats, and that’s something that we work really hard to educate the public about, because that’s something that can be prevented.

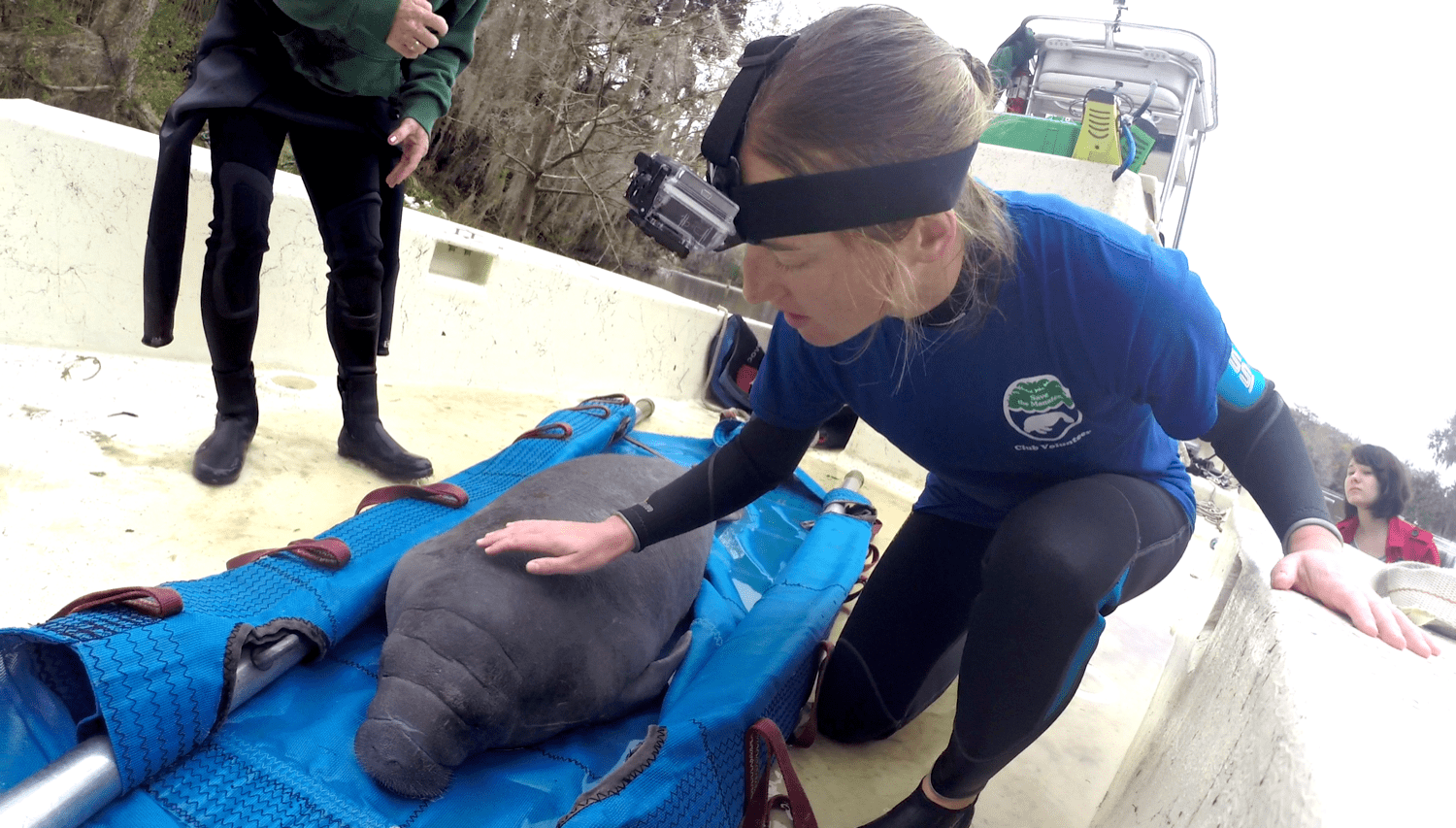

The thing that we deal with normally, in a normal winter, is cold stress. So these animals are not adapted to be in cold water. So as our climates change and the environment changes, sometimes we can see animals having a hard time with that. So we just released three animals the last couple of days. And all three of those animals came to our critical care facility because of this syndrome called cold stress.

So they’re in water that’s too cold for them. For whatever reason, they didn’t make it into warm water. They didn’t know how to go into warm water, or the area that they normally would have been in became colder that year because the climate is changing. And they become very, very ill from that.

MILES O’BRIEN: And how is that related to the lack of seagrass?

PATRICK ROSE: Yeah, it really has come together in the Indian River Lagoon in a way that the manatees are having to make that terrible choice between staying warm and not dying of cold stress, or literally starving to death over a longer period of time. So they’re coming into the winter less fit. They’re already malnourished quite a lot. And so as they have to stay there and forego feeding, it leads further to starvation.

That’s one of the things that’s being looked at this year. We thought it would never happen, but there’s an actual supplemental feeding program that’s being established for that area along the east coast. It’s having some limited success so far. But it has a long way to go before it’s going to be able to forestall continued starvation this winter.

MILES O’BRIEN: And that supplemental feeding program, just to help people understand– they’re actually around power plants, where the manatees gather in the winter because the water, the discharge water, is warm. They’re actually throwing in romaine lettuce to try to feed the manatees, which gives you an idea of how desperate the situation is.

CYNTHIA STRINGFIELD: One really important thing related to that, and to speak to the prior thing, too, is my understanding is that the manatees have learned over many, many, many years that they actually migrate to certain areas during the winter. And so they migrate to this Indian River Lagoon area because historically that has been a really good place to be. So that makes it really awful, too, that they’re going to this place that has normally been a good place in the wintertime, and there’s just no food there.

As far as the feeding program, something we really want to get out to the public, because this is the question we get all the time, is, if we see a manatee, can we just chuck them some lettuce and feel like we’re helping the situation? And it’s been a really difficult nut to crack, because you don’t want these wild animals becoming dependent on people feeding them. And you also don’t want them making that connection behaviorally that, oh, this is a good place to go because somebody’s going to throw me some lettuce, and then that person stops doing it, or it’s just a random thing.

So it took a lot of time for them to figure out how to do this feeding program in a real scientific, appropriate way so that it’s targeted in the right location and it’s not associated with people. It’s feeders out there that are not actual people giving them food and that sort of thing. So we really plead with everybody that if you see any manatees that you’re concerned about– in bad body condition, or they look like they’re sick, or they’ve been hit by a boat, or anything like that– to call them in, because there are rescue crews that will go out and assess the situation and help take care of them the appropriate way and instead of throwing food or doing what you think might be helpful.

MILES O’BRIEN: Yeah. Pat, it seems like Florida lawmakers may be headed in the wrong direction on this. I know they’re considering a bill that would actually make it easier for people to plow over or dump landfill on seagrass, which of course is the source of food for the manatees. And the bill would create ways to mitigate it by planting it elsewhere. Is this a good idea?

PATRICK ROSE: It’s a terrible idea. In fact, what you would be doing is setting up some of the best seagrass areas in Florida, those that have made it through a lot of tough times and situations, and then allow those to be taken away or smothered in the promise that you might be able to restore seagrass in other places. And we know with wetlands, banks and things like that, they don’t work well. They’re really a way to sort of bait and switch, get more development, more of that non-sustainable growth and development, and not paying the proper price for that. And so it’s just a further way to cause more losses in seagrass and losses of some of the best remaining seagrass areas.

MILES O’BRIEN: So tell us what laws are on the books right now, either at the state or federal level, to protect manatees? And are they good enough?

PATRICK ROSE: So the basic federal law would be the Endangered Species Act. Manatees were, we feel, unceremoniously down-listed, without the right biological force behind that, to a threatened species in 2017. We warned them about these kind of problems manatees are facing. And there is a very good state law. It’s the Manatee Sanctuary Act that we helped establish, really going back to the early 1970s as well. It has the right force of law, but it needs to be better supported.

And the funding for the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission needs to be increased, their staffing. Both at the federal level and the state level, the staffing and funding for those programs had been going down over these years, and they were getting behind, after it being one of the most stellar recovery programs we’ve had historically. We had decades of wonderful progress. But this last decade when things were really starting to get worse, the politics began to override the science. And we’ve got to return to that, or we’ll be seeing more of these kinds of problems.

If you look at Tampa Bay, they went through major seagrass loss in the 1950s and ’60s. They woke up to that in the ’70s. They restored most of that habitat, and they controlled the sewage discharges, the dredging, the filling. But now it even is starting to decline again. Same for Sarasota Bay, Biscayne Bay.

So we’re seeing early signs of problems in all of our major aquatic ecosystems in Florida. There’s time to do something about it. We’re getting lip service now from the legislators and those that are in charge, but we need to see more done, and soon enough that we can really turn this around.

MILES O’BRIEN: I’m Miles O’Brien. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. We’re talking about turning around the crisis hitting Florida’s manatees. But turning something like this around, when you consider the causes here, it’s like turning an aircraft carrier around. It’s going to take time. And the manatees don’t have the kind of time that this process might take. How concerned are you for their future, collectively?

PATRICK ROSE: Well, for the east coast of Florida, I am very concerned. We lost about 20% of the east coast population last year. We’re on a track to lose another 10 or more percent, depending on how successfully we can– the supplemental feeding can go, whether we have space.

Cynthia, the folks at Zoo Tampa, are doing a remarkable job, but they can only do so much. And so we have a team that includes the federal and state government as well as the zoos and aquariums, but we don’t have enough space to really deal with all the manatees that need to be rescued. We’re still working on increasing that, but we’ve got to do more.

And so while there’s some restoration work already started, we’re talking about a decade or more to really restore that ecosystem. And in the meantime, these manatees are again facing not just the cold, not just the starvation issue on the east coast, but nearly every manatee alive today has been hit by a boat and scarred. And we’re losing 100 or more manatees every year to watercraft.

MILES O’BRIEN: Cynthia, final thought here on manatees? You work with them so closely. Are they resilient?

CYNTHIA STRINGFIELD: They’re incredibly tough patients. I can tell you as a manatee doctor that they aren’t fragile. They come back from things that you cannot believe they can come back from. So that’s always especially scary to me, I think, when you link that to what’s going on in our ecosystem, because these are all things that affect humans as well.

I’ve been part of some interesting conversations with fishermen and people that make their livelihood on the water, and they’re suffering as well. We have red tide problems because of other issues. And they kill off a lot of other wildlife in addition to manatees. So the manatees are trying to hang in there, and they’re– I look at them as kind of the canary in the coal mine for all of us, that when you have an animal that’s been around for this long and has hung in there through so many things and, like Pat was saying, has been able to rebound when we do the right thing, and when you look at what’s going on with them right now, it should be a huge wake-up call to everybody.

The good thing is that Florida loves its manatees. You won’t find a person that doesn’t like a manatee and isn’t so proud to have them as the animal here for Florida. And so I’m just really hopeful that people care. They really do care, and they’re listening, and they want to do what’s right for the manatee. And in turn, they’ll be doing what’s right for the state and what’s right for themselves and their families in living here.

MILES O’BRIEN: Well, hopefully, once again, people will rally to save the manatees and ultimately save the waters in which they live. That’s all the time we have for now. I’d like to thank my guests, Patrick Rose, executive director of the Save the Manatee Club in Maitland, Florida, and Cynthia Stringfield, senior vice president of animal health, conservation, and education at Zoo Tampa in Tampa, Florida. Thank you both.

CYNTHIA STRINGFIELD: Thank you

PATRICK ROSE: Thank you.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

Miles O’Brien is a science correspondent for PBS NewsHour, a producer and director for the PBS science documentary series NOVA, and a correspondent for the PBS documentary series FRONTLINE and the National Science Foundation Science Nation series.