A New Book Puts ‘Math in Drag’

17:18 minutes

Listen to this story and more on Science Friday’s podcast.

It’s a common refrain from elementary school to adulthood: “I’m bad at math.” It’s a hard subject for a lot of people, and it has a reputation for being—let’s face it—boring. Math isn’t taught in a flashy way in schools, and its emphasis on memorization for key concepts like multiplication tables and equations can discourage students.

It’s not hard to understand why: Math has long been seen as a boy’s club, and a straight, cis boy’s club at that. But Kyne Santos, a drag queen based in Kitchener, Ontario, wants to change that.

@onlinekyne Replying to @Socrates 😱 one of the most important intervals in music is the fifth, but why does the fifth sound so good? Let’s use math to explain harmonies! #math #music #harmony #starwars ♬ original sound – Kyne

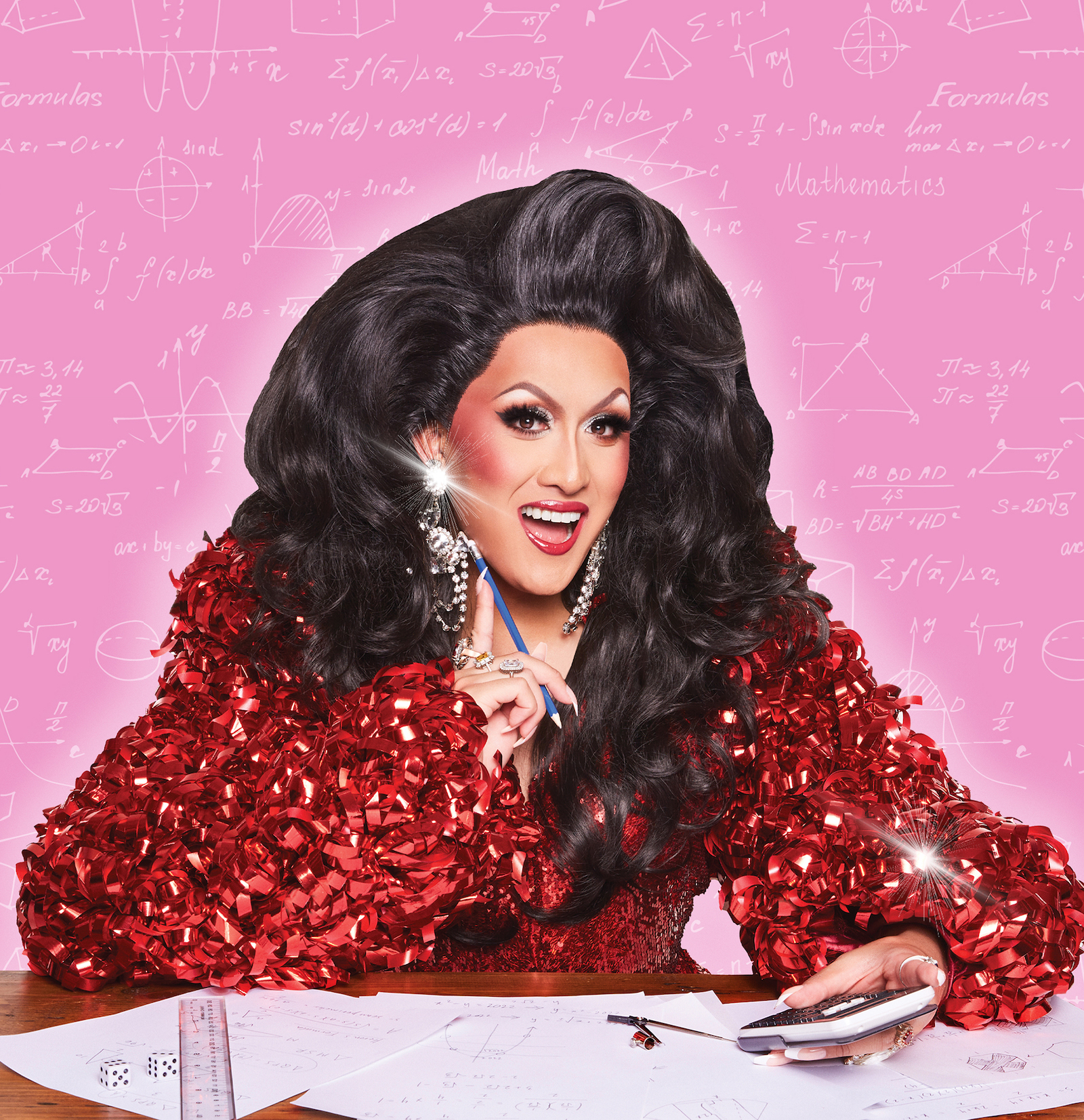

Kyne is on a mission to make math fun and accessible to people who have felt like math isn’t for them. Her new book, Math in Drag, is one part history lesson, one part math guidebook, and one part memoir. Kyne speaks with Ira about “celebrity numbers,” Möbius strips, and why math and drag are more similar than you may think.

Kyne Santos is the author of Math in Drag, and is a mathematician and drag queen based in Kitchener, Ontario, Canada.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. You know, math has a reputation for being kind of dry and boring. Apologies to you math lovers, but it’s not the flashiest subject. But what happens when math is combined with one of the flashiest art forms– drag? Yes, the result is a book by my next guest Kyne Santos, author of Math In Drag. Kyne is based in Kitchener, Ontario. Welcome back to Science Friday.

KYNE SANTOS: Hi, Ira. Thanks so much for having me.

IRA FLATOW: You’re quite welcome. All right, you know, at first glance, I don’t see a lot of similarities between math and drag. But your book is an argument that they are similar. Tell us about that.

KYNE SANTOS: Yeah, people think that these are two such separate worlds. We have drag, which is art, and art has no rules. Whereas people think that math is just full of arbitrary rules. But what the book tries to argue is really that math is about thinking creatively and working collaboratively and thinking innovatively and questioning our pre-held stereotypes and beliefs.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, so tell me about your personal background with math. Did you always love it?

KYNE SANTOS: I remember always being pretty good at it. It was always my best subject, ever since I was a little boy.

IRA FLATOW: Really?

KYNE SANTOS: Yeah, my dad was an engineer. He would just do my math homework with me, and I just always wanted to impress him. I started liking math and thinking that it was beautiful when I was in high school. My math teachers encouraged me to start writing math contests, which were these extracurricular math tests– didn’t count for your grades. They were just an extra challenge.

I know everyone was listening thinking, where can I sign up? But you know I loved it. And I saw through it a different side of math where it wasn’t just about using an algorithm that your teacher taught you. It was about problem solving and thinking on the spot. Thinking outside the box.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. I had a great math teacher who used to describe geometry as elegant. He’d say the proof was elegant. So I really enjoyed that. And for a long time, math has been considered a boys’ club. Was it like that to be a math lover who didn’t fit that neat little box?

KYNE SANTOS: Yeah. And I mean, I guess, growing up as a boy, I sort of had the privilege of feeling like math was sort of open to me in that respect. I know that math is, as you say, a bit of a boys’ club. I, in particular, felt it was a bit of a straight boys’ club. I felt that if I came out as gay, that people wouldn’t really take me very seriously.

I always thought that the stereotype behind gay people were that they were just sort of flamboyant, very vapid. I didn’t really think that they could become mathematicians or scientists. So the book is really aimed at people who need to unravel this stereotype. I want to show people that anybody can be a math person no matter who you are or what you look like.

IRA FLATOW: That’s really good. I want to get into some examples then of how math can be flashy and fun. Tell me about the different levels of infinity. I know when I was back in school studying Georg Cantor’s aleph sets, right? There were different infinities, right?

KYNE SANTOS: Yeah, yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Is that what you’re talking about?

KYNE SANTOS: Yeah, the book talks about Georg Cantor and these different levels of infinity. I mean, first of all, we have– there are infinite numbers. You can start from 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and then they never stop. But that’s what we call countable infinity because you can put them on a list.

IRA FLATOW: Right.

KYNE SANTOS: There’s an uncountable infinity, which is all the numbers just between 1 and 2. All the decimal numbers, like 0.1, 0.15, 0.001. It turns out there’s an even greater infinity of numbers just between 1 and 2, and the book explains why that is.

IRA FLATOW: That is a mind blower to think that one infinity can be bigger than the other infinity.

KYNE SANTOS: Yeah. Yeah. Not only that, but there are greater infinities even than that. You can keep taking an infinite set and then using that to build an even larger infinite set. There are infinite infinities.

IRA FLATOW: I love it. OK, speaking of infinity, let’s talk about one number with infinite digits which we all love, pi. Pi day is coming up very soon, right? This is a concept that most people are probably familiar with, and you use the concept of pi to make drag outfits for yourself. Wow.

KYNE SANTOS: Yeah. Yeah, well pi is the relationship between a circle’s circumference and a circle’s diameter. So if you’re making a skirt that you want to fit nicely around your waist, you can take a measuring tape, measure around your waist, that’s the circumference. But when you go to the fabric to cut it out, you’re cutting out a radius to make the circle. So you have to use pi in that equation.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. I was reading the parts where you were talking about cutting out different kinds of circles that fit different body forms.

KYNE SANTOS: Yeah, yeah. Well, pi is the same. Whether it’s a large circle or a small circle, the circumference is always pi times the diameter of any circle.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. And you devote a chapter in your book to what you call celebrity numbers. The rebels and the punks over the number world. Give me an example of a celebrity number.

KYNE SANTOS: That’s right. Pi is one of them. The others are zero and i, the imaginary number. And I call them celebrity numbers and I call them punks because these are numbers that challenge our ideas of what a number is. We used to think that numbers were just things you could count. You had one sheep, two sheep. The idea that nothingness could be a number was something that was a bit novel to the Romans. And so that’s why there is no Roman numeral for zero. There was no year zero.

IRA FLATOW: Zero had to be invented, right?

KYNE SANTOS: Yeah, it had to be invented. And so the fact that there are numbers that we don’t know exist but that do fit into the framework– once we do accept the idea of zero as a number, it also opens the door to negative numbers, which is a hard thing to wrap your head around. But once you do, it’s like, yeah, it works perfectly for describing debt, for describing below zero temperatures.

And it’s a great analogy to drag because just as there are new sorts of numbers that we may not understand, there are all sorts of people that, at first, when we meet them, we don’t always understand who they are or why they’re like that. But you want to have an open mind when it comes to math and when it comes to life.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, especially when you get into imaginary numbers, which I’ve always had a lot of trouble with.

KYNE SANTOS: Yeah. Yeah, students have a hard time wrapping their heads around that. I did as well. The idea that you can take the square root of a negative, it’s hard to imagine, no pun intended, because a negative times a negative is a positive. 0 times 0 is 0 and a positive times a positive is positive. So how do you multiply a number by itself and get a negative number?

Well, you just invent it. And it turns out that it works quite well in math. We can use it in computer science, in electrical engineering, in physics. And it has all of these applications and it actually works quite well. Just like how negative numbers fit into our framework quite well, you can say numbers are this and this is our framework and that doesn’t work or you can expand your framework and make it all the more fabulous and wonderful.

IRA FLATOW: We’re taught that math has very rigid rules, but you say it doesn’t have to be that way.

KYNE SANTOS: No, no. This is, I think, the problem of how math is taught. We teach math as if we were teaching kids to paint by having them paint a fence. It’s just all about following these rote rules where really math is about thinking creatively. And the idea of accepting new sorts of numbers is one example, but a lot of modern mathematicians are thinking creatively and working on original ideas. And they’re questioning axioms and tinkering with well, if we tweak this, then what happens here?

IRA FLATOW: Right.

KYNE SANTOS: And finding these connections.

IRA FLATOW: Right. Because you always have these things where if you’re doing multiplication, a long string of numbers or addition, you do this stuff inside the parentheses first, right? Then that stuff on the outside. So you have those rules, but they’re not always agreed upon.

KYNE SANTOS: No. And listen, drag has rules too. If you watch Rupaul’s Drag Race or if you go to a drag pageant, there are rules that drag queens have to abide by as well. So there are these constraints that we put on to help us understand what drag is about and how drag is different from other art forms. Constraints oftentimes can help you be even more creative.

IRA FLATOW: And speaking of that, this concept of illegal numbers makes me think of drag and the way it’s been made into a bad guy in the eyes of some people.

KYNE SANTOS: Oh, yeah. I mean, I go on and on talking about my experience with the trolls online, people coming after drag queens. I talk about in the book how math has been controversial and how numbers have been illegal. When zero was first invented, people had a hard time grappling with that, that zero and the rest of the Hindu-Arabic numerals were also illegal at one point.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, and so how do you keep your head up against the people who say drag queens should not be teaching kids about math or even existing at all?

KYNE SANTOS: I just have to keep my head up, and I just have to lead with positivity and light. I know that what I do is not for everyone, and I’m not going to change everybody’s mind. But I just want to lead with love and positivity and be a good role model. And show people that we’re more than just a stereotype. Really, my goal is to change people’s opinions about math and also change people’s opinions about drag.

IRA FLATOW: Speaking of which, let’s talk about your very popular TikTok page.

KYNE SANTOS: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: Where you teach math concepts in a really fun and visually engaging way. I want to ask you about the Mobius strips, which is something that you talk about on your channel a lot. Tell us what a Mobius strip is.

KYNE SANTOS: Yeah, well, the Mobius strips are great because they’re a great visual example. You can make one with a piece of paper. You just cut out a long rectangle, you flip it 180 degrees, and then tape it back together. And then you get this thing that you can play with that is one sided. If you trace your finger all the way around, you end up back where you started having touched both sides because it’s all one side.

And I think that people like it because it’s this visual thing that they can really connect to. And TikTok has just been so magical because it’s allowed me to reach millions and millions of people. People who wouldn’t have otherwise looked up a math video. People who have graduated from school and probably thought they would never want to take a math class again are suddenly now interested in math and wanting to talk about it in the comment section, talk about it at the dinner table.

IRA FLATOW: And what’s your strategy for teaching a really complicated math concept to people who maybe have no background in the subject? How do you break things down in a way that’s, so to speak, digestible for people?

KYNE SANTOS: I think the key is really I don’t try to get them to memorize it, like we do in school. What I explain is why these concepts are the way they are. I try to really explain the logic behind things and also how they’re used in the real world. I think that’s what’s maybe missing from our education system.

IRA FLATOW: Not only are you a mathematician and a drag queen, but you’re also a musician. Let’s talk about music theory because don’t we know that musicians and mathematicians really have an intersection there?

KYNE SANTOS: Yeah. OK, well, I wouldn’t call myself a musician. I suppose I’m a music lover.

IRA FLATOW: I’ll take that. I’ll take that. Close enough.

KYNE SANTOS: Yeah, well, I mean, over the holidays I was just learning about math and music. And what’s amazing is that music, something else that we think is so artistic, actually has a lot of math behind it. Behind the way a piano is tuned, even a sound wave. Whoever is listening to this right now, so much math has to happen for the sound waves to be fed into the microphone and then through the speakers and then fed through the wires as encoded in zeros and ones. It’s really brilliant, if you think about it.

IRA FLATOW: So then music could be possibly a good way in, a door for people.

KYNE SANTOS: Yeah, I mean, I think what’s great about music is that everybody can connect to it. People realize that you don’t have to be a music expert in order to listen to music on the radio and really appreciate it. And I want to say that you don’t have to be a mathematician to appreciate math and to enjoy the masterpieces of math.

IRA FLATOW: And who would you say, because people always ask authors, who did you write this book for? Do you have a specific audience in mind here?

KYNE SANTOS: I wrote this book for college students, high school students, adults, people who maybe don’t have a great relationship with math. I want to help repair that relationship, and show them that math doesn’t have to be this challenging, cold, hard, calculating subject that you remembered in school. It can be something that’s fun and inspiring and is actually present in everywhere we look around the world around us. I just want to show people that you can just love this universe. And math is the language of our universe.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, that’s another way of saying, and you say this in your book, that math is magical.

KYNE SANTOS: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Right.

KYNE SANTOS: It is magical.

IRA FLATOW: And you rarely hear people who are not mathematicians who are not involved with math talking about it being magical. Make an argument for me about math being magical.

KYNE SANTOS: I mean, I’ll talk about pi since we talked about that. Pi is everywhere. You can use it to make a dress, but it’s also got infinitely many digits and yet we only need a few of them to make a dress. And we only need even 15 of them to land rockets on the moon.

With the first 40 digits of pi, you can estimate the circumference of the entire observable universe within atoms with margin of error. And yet, it has infinitely many digits. And it may or may not have your phone number, your credit card number encoded within it. Could be the entire works of Shakespeare and the bible. I think infinity is just this magical concept, and yet, it exists in our own heads.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. And speaking of pi, you talk in the book about how many different cultures discovered it independently. That it was something that had to be discovered.

KYNE SANTOS: Yeah. I think the other magical thing about it is if it is in our heads, then why did so many people discover it independently around the world? You had the ancient Egyptians, the ancient Greeks, ancient China, India, Mesoamerica all coming up with number systems, all coming up with their own expressions of pi and algebra and sort of landing on these similar math concepts.

There’s two schools of thought. You can say that math is sort of invented by us and exists in our heads or it’s out there in the real world.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah.

KYNE SANTOS: If it’s invented in our heads, well, it works really well.

IRA FLATOW: Right.

KYNE SANTOS: And it is so good at describing the universe. And if it’s out there, then where is it? Is it in the sky? Is it in the– where is it out there if it’s a physical thing? I don’t know.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. It’s kind of spooky. I mean, in a good way. So what do you say to people who aren’t good at math but would like to be good at math, would like to discover what you have discovered?

KYNE SANTOS: I would say that learning never stops at any age, even when you graduate school and you get your diploma. For me, I’m a lifelong learner. And I’ve always just wanted to learn more about this universe and the people we share it with. And you should never put any limiting belief on yourself and say I’ll never learn math. It’s like saying I’ll never learn another language or I’ll never read another book. Why say that to yourself? I think we should all embrace an enthusiasm for learning because what else are we here on this planet for?

IRA FLATOW: And it also takes a good teacher, like yourself, to be able to explain it to people who really want to know about it.

KYNE SANTOS: Oh, I appreciate that. Thank you. And I, you know what? I want to give a shout out to all the other teachers out there in the world working in the classrooms because they’re molding the minds of this next generation of humans.

IRA FLATOW: And there you have it. Kyne, thank you for what you do and for taking time to be with us.

KYNE SANTOS: Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. Kyne Santos, author of Math In Drag, a really cool new book out this week. Kyne is based in Kitchener, Ontario. And we have an excerpt of the book on our website. Yes, sciencefriday.com/mathindrag. Check it out.

Copyright © 2023 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.