A Saltwater Wedge Is Moving Up The Mississippi River

7:41 minutes

This article is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story, by Halle Parker, was originally published by WWNO.

As the Mississippi River drops to one of its lowest levels in recent history, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers said salt water from the Gulf of Mexico could threaten drinking water as far north as New Orleans’ French Quarter if no action is taken.

On Friday, the Corps announced plans to avoid that scenario by building upon an existing underwater barrier that has been in place to block the progression of salt water from intruding farther upriver since July. At its current height, the Corps expects the salt water creeping up the bottom of the Mississippi River to overtop the barrier later this week, sometime around Sept. 22.

If that were to happen, the salt water would begin affecting drinking water in Belle Chasse by early October.

A pervasive drought throughout the Mississippi River Valley allowed seawater to encroach inland earlier this summer. By June, the residents living in lower Plaquemines Parish were forced to go without fresh drinking water and have been relying on water distributed by the parish.

Currently, Plaquemines Parish President W. Keith Hinkley said about 2,000 residents can’t drink their water due to salt contamination, and the parish has distributed more than 1.5 million gallons of water with little signs of reprieve. If the salt water reaches Belle Chasse, at least 20,000 more residents would be affected.

This phenomenon, known as a “saltwater wedge,” typically occurs once per decade. But 2023 marks the second year in a row where drought has left the Mississippi River’s flow far lower than normal.

Army Corps Col. Cullen Jones said forecasts suggest the river’s flow could drop to 130,000 cubic feet per second by mid-October, less than half of the amount of freshwater needed to push the salt water back down to the Gulf of Mexico.

The lowest recorded flow down the Mississippi River happened in 1988, dropping to just 120,000 cubic feet per second, allowing the wedge to intrude as far north as Kenner.

“So while the river level is not unprecedented, we are very close, and with no rain forecasted in the valley, we do not predict positive outcomes for the near future,” Jones said.

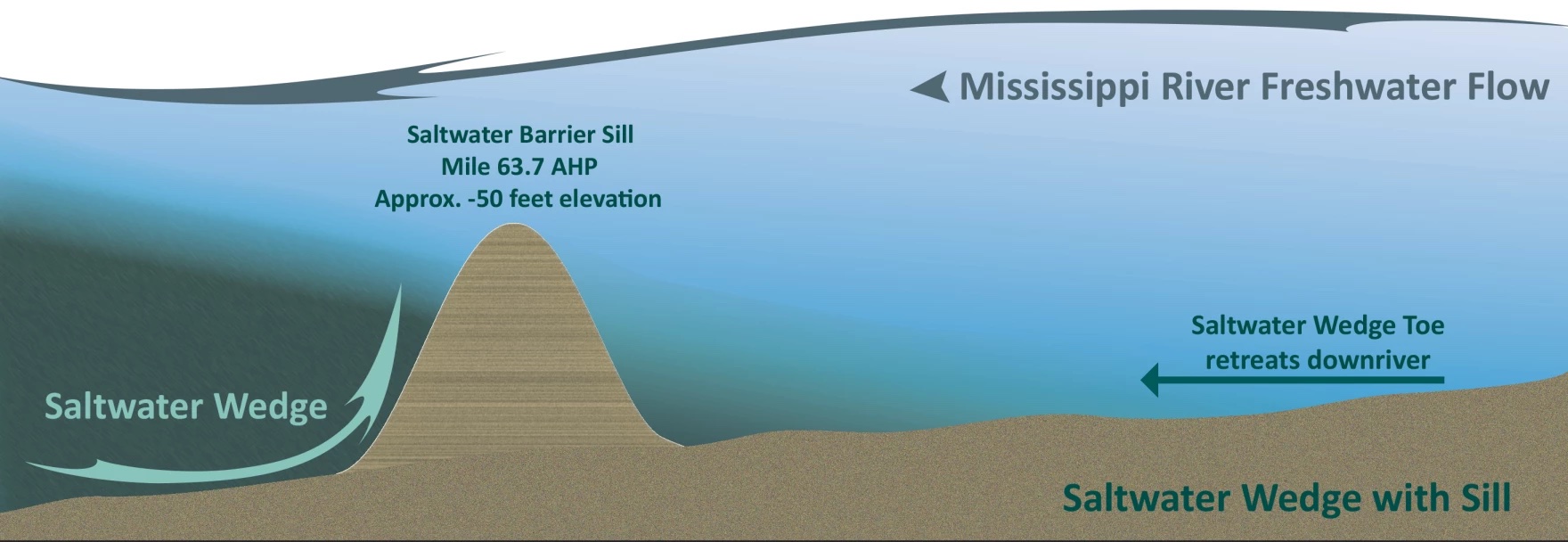

The wedge is made up of a dense strip of ocean water that sinks beneath the river’s freshwater during periods of low flow and slowly pushes north under the fresh layer. This happens because salt water is denser than fresh and because the bottom of the Mississippi River is below sea level throughout the entire length of Louisiana.

The Corps’ current underwater barrier, or sill, will block the wedge’s migration near Alliance, about 13 miles south of Belle Chasse and nearly 64 miles upriver from the Mississippi’s mouth. As of Sept. 13, the tip of the wedge extended about 56 miles upriver from the mouth, according to the Corps’ website.

Jones said they want to raise the sill, while still allowing ships to pass by creating a notch in its center. That notch will be a 625-foot stretch that sits about 55 feet beneath the water’s surface, while the wings would sit about 25 feet higher. In that location, the whole river is about 2,700 feet wide.

But without more rainfall in the drought-stricken Mississippi River Valley, Jones said this plan will likely only be enough to buy the Corps additional time to provide Plaquemines and St. Bernard parishes with more resources.

Jones said the Corps will also look into the possibility of shipping enough freshwater from higher up the river in barges down to affected water-treatment plants in order to dilute the saltiness to safe drinking levels. The agency will also give smaller treatment plants technology to remove the salt and purify the water. The units use reverse osmosis to desalinate water by pushing it with extremely high pressure through a thick filter.

Officials said that if your water supply becomes tainted with seawater, do not drink it unless otherwise advised. Ingesting salt water can lead to health problems like high blood pressure. Residents should also be on the lookout for damage to appliances like dishwashers or coffee machines because salt water can be corrosive.

As the planet continues to warm due to human-caused climate change, extreme weather like droughts is expected to happen more frequently than in the past.

“What we can see is just the facts of extreme weather events occurring in more frequent periods. We’ve seen the implementation of the saltwater wedge in the period of less than a year, and we’re also undergoing a significant drought that’s pretty much becoming comparable to the 1988 drought,” Jones said.

When asked if long-term adaptation is needed, Jones said the Corps is undergoing a 5-year study of the lower Mississippi River that will examine the effects of more saltwater intrusion and ways to reduce its impact in the future.

Climate scientists agree that the main way to reduce the potential impact of climate change is to steeply, and quickly, cut new greenhouse gas emissions, driven mainly by burning fossil fuels like oil and gas.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Halle Parker is a Coastal Desk Reporter for WWNO in New Orleans, Louisiana.

FLORA LICHTMAN: This is Science Friday, and I’m Flora Lichtman. And now it’s time to check in on the state of science.

[AUDIO PLAYBACK]

– This is KERN.

– For WWNO.

– Saint Louis Public Radio.

– Iowa Public Radio news.

[PLAYBACK ENDS]

FLORA LICHTMAN: Local science stories of national significance– today, we’re talking about a saltwater wedge. I know it sounds like a menu item at Sweetgreen, but it’s actually a natural phenomenon. Seawater from the Gulf of Mexico is slowly creeping up the Mississippi River. And this is making waves for some Louisiana residents. This salty slurry can contaminate drinking water.

So how are cities preparing? And what does this mean for people living on the river? Here to tell us more is my guest Halle Parker, coastal desk reporter for WWNO Public Radio in New Orleans, Louisiana. Welcome back to Science Friday.

HALLE PARKER: Hi, Flora.

FLORA LICHTMAN: What is the science behind a saltwater wedge? Why does it happen?

HALLE PARKER: Yeah, OK. So there’s a couple things going on here. You might actually be surprised to learn that the bottom of the Mississippi River sits below sea level throughout its entire path in Louisiana. So that means that the Gulf of Mexico can actually creep up if given the chance. And usually we don’t have a wedge because the force of the freshwater flowing down the Mississippi River actively pushes against the Gulf of Mexico to keep it back at the mouth of the river. It acts kind of like a barrier, for the most part.

But we’re in the middle of a drought, so not a lot of rain has been falling. And that means there’s less water flowing down the Mississippi, River. So we lose that barrier. And it leaves an opening for the denser saltwater of the Gulf of Mexico to encroach up the river underneath the freshwater that’s still flowing downstream and increase the salinity as it moves up river.

FLORA LICHTMAN: How often do these saltwater wedges happen? Is it unusual?

HALLE PARKER: Not necessarily. In general, this saltwater wedge is, like you mentioned, this natural phenomenon. And historically, it’s happened on a cycle, like once in a decade. But this year is different.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Why? In what way?

HALLE PARKER: So there’s a few things. This is the second straight year that this saltwater wedge has formed, breaking from past trends. Last year it didn’t stick around that long, and it stayed closer to the mouth of the river, isolated to the lower end of this parish that’s south of New Orleans called Plaquemines Parish. And so last year’s wedge was normal, so to speak.

But two back to back years with historic droughts and little rainfall forecasted in the coming months means that this year’s saltwater wedge might extend farther upriver and threaten drinking water of almost a million people in the greater New Orleans area. That happened one time back in 1988, just for historical context. But the wedge only made it this far for a few days before retreating. But this has the possibility of sticking around for a lot longer.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Wow, a million people. So how does the wedge affect drinking water?

HALLE PARKER: So this is an issue because the Mississippi River is literally the source for drinking water for this region. So that’s where the water treatment plants are literally sucking in the water that’s been pumping to people’s taps after treatment. So if the Mississippi River gets saltier, then our tap water gets saltier, too.

FLORA LICHTMAN: How are people preparing? How are cities preparing?

HALLE PARKER: Yeah. So preparation really depends on population size and how much water each parish needs. For some of the smaller plants, their plan is to get fresh water from farther up river shipped down in barges to blend with the water they’re pulling from the river if the saltwater wedge happens to reach them. Those smaller plants are also renting this equipment called reverse osmosis purification units, which is a mouthful. And that can remove the salt from the water with the process called desalination.

But the bigger plans for areas, like New Orleans and surrounding suburbs, really need more water than those options can provide. So local officials are looking to rapidly build pipelines that will draw millions of gallons of fresh water from a point farther up river, similar to how those barges are working. Their focus has really been on making sure that the amount of salt in the water stays low, both for people’s health and other reasons.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Wow. Have you heard from residents? Are people concerned about this?

HALLE PARKER: Yeah. So really, I’ve been getting a lot of questions. There’s just a lot of fear and anxiety about what could happen, especially since there’s still so much uncertainty about just how bad this water emergency could be. And we won’t have a lot of answers until the salt water actually gets up here, if it does. And that unknown can be scary. People want to know how to prepare.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Does it impact residents in any other way besides their drinking water?

HALLE PARKER: Yeah. So salt water actually speeds up the corrosion to metal. And that can affect pipelines throughout cities, so that’s a huge concern. But another concern is also people’s appliances, like washing machines, air conditioning, dishwashers. All of that can be damaged.

And in Plaquemines Parish, they already have been. I went down there last week and talked to a fishing guide named Jamie Taylor. He works out of a community called Venice. And he said it’s been really bad.

JAMIE TAYLOR: If you drive up and down the road, you’re going to see hot water heaters sitting by the road because people have had to replace them.

HALLE PARKER: And this stuff can be expensive to fix. So those residents that have been affected are looking for help with money to replace them. And residents who haven’t been affected want to know how they can avoid the problem in the first place. But that’s another thing that we don’t have all the answers to yet.

FLORA LICHTMAN: How do these wedges go away?

HALLE PARKER: Yeah, so it all comes down to rain, pretty much. We’re not expecting much down here in the next few months. So we’re really waiting on rain to fall up in the upper Mississippi River Valley, the Ohio River Valley, and then make its way downstream and increase the flow of the Mississippi River so it’s able to push that salt water back to where it came from in the Gulf of Mexico.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Right now, the projections for the wedge’s whereabouts last until the end of October. Could it actually last longer than that?

HALLE PARKER: Yeah. Actually, the Army Corps of Engineers has warned local officials to just be prepared for this saltwater to actually stick around for up to 90 days. That’s like three months, so almost in January. So we could be dealing with this for a pretty long time.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Oh wow. Are these saltwater wedges linked to climate change? If it’s about drought, are people worried we’re going to see more of them in the future?

HALLE PARKER: Yeah, that’s a really important question. The researchers that I’ve spoke to have said that climate change is one of the factors leading to this saltwater wedge being so bad this year. Because climate change is known to make extreme weather, like droughts, worse, we could potentially expect this to happen more often than it has in the past. Now, the researchers I’ve talked to have cautioned against thinking about this incident as like a new normal. It’s not something we would necessarily see every year. But it is something that we could see happen more often than in the past than on that decadal cycle. So that means that local officials need to start thinking about long-term adaptation, especially since this will probably happen again.

FLORA LICHTMAN: That’s all we have time for. I’d like to thank my guest, Halle Parker, coastal desk reporter for WWNO Public Radio in New Orleans, Louisiana. Thank you for joining me.

HALLE PARKER: Thanks, Flora.

Copyright © 2023 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

Flora Lichtman is a host of Science Friday. In a previous life, she lived on a research ship where apertivi were served on the top deck, hoisted there via pulley by the ship’s chef.