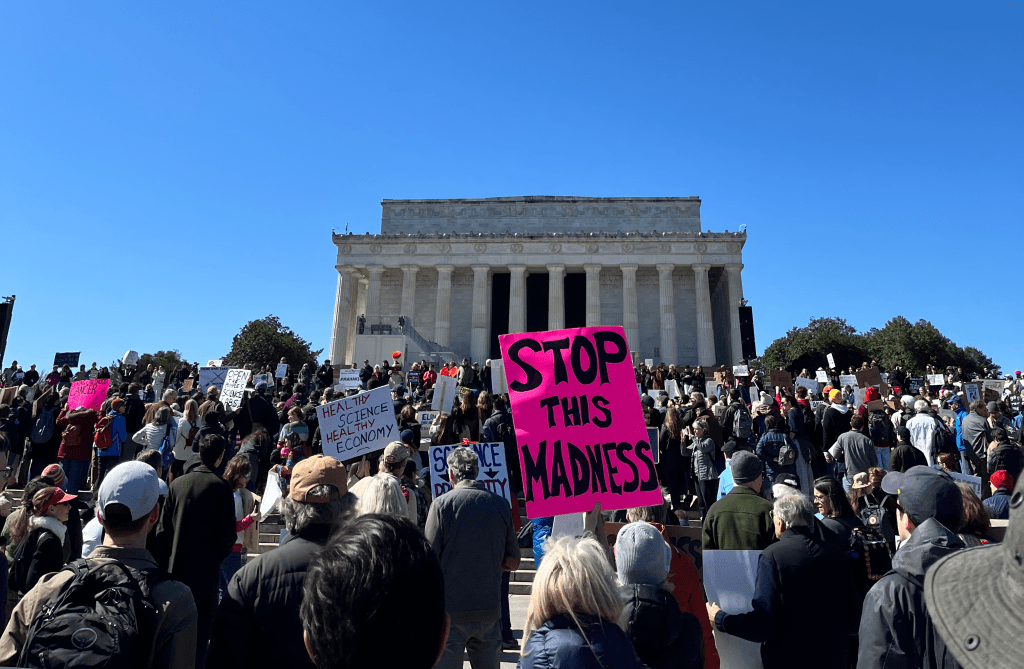

Protesters ‘Stand Up For Science’ At Rallies Across The Country

11:59 minutes

Scientists and defenders of science are gathering in cities across the U.S. today as part of Stand Up for Science rallies, events to protest recent political interference by the Trump administration in science funding. The main rally in Washington, D.C. features speakers including Bill Nye, Dr. Frances Collins and Dr. Atul Gawande, and will advocate for ending censorship, expanding scientific funding, and defending diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Host Flora Lichtman speaks to science reporter Anil Oza, a Sharon Begley Fellow at STAT and MIT, about the runup to Stand Up For Science, and what he’s heard from organizers and attendees. Then, Flora speaks with two listeners, D.C.-based planetary scientist Mike Wong and University of Louisville student Emily Reed, about why they’re fired up to attend local rallies.

Keep up with the week’s essential science news headlines, plus stories that offer extra joy and awe.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Anil Oza is a science reporter for STAT and MIT, based in Boston, Massachusetts.

FLORA LICHTMAN: This is Science Friday. I’m Flora Lichtman. Later in the hour, a trip back in time to look at prehistoric plants. But first, today, scientists and concerned citizens are taking to the streets in cities across the US to protest the Trump administration’s science policies. Joining me to fill us in on the Stand Up for Science rallies is Anil Oza, reporter for STAT at MIT based in Boston, Massachusetts. Welcome back, Anil.

ANIL OZA: Hey, Flora. Good to be back.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Tell us about Stand Up for Science. What is this rally all about?

ANIL OZA: Yeah, this is a rally put on by a handful of scientists to support science. It has a very vague goal, but it is to protest a lot of the movements that the Trump administration has made to attack the scientific process and the institutions of science.

FLORA LICHTMAN: And where are the events?

ANIL OZA: So these events are going to take place across the country and actually across the globe. But there are 32 official protests that are affiliated that are mostly in state capitals. And the biggest one is in Washington, DC. But there’ll be a lot of large ones in cities that are very popular, sort of university or research towns. So I’m in Boston. That is slated to be a pretty big one. New York City is also slated to be pretty large, as is Seattle and LA.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Are the big science orgs standing up for the Stand up for Science March?

ANIL OZA: No, they are. And I think that’s one of the key differences between this march and the science march that happened during Trump’s first term, which is the March for Science. In 2017, almost every major scientific society that you could think of formally endorsed the March for Science. But we’re not seeing that this time.

And I think it speaks to the sort of weird moment we are in politically, where scientists are very upset and stressed about the future of the scientific enterprise here in the US. But there’s also a lot of fear, particularly at the top, to speak out against the Trump administration and to further target themselves.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Even at these big science orgs?

ANIL OZA: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, like a notable exception here is that the AAAS, which is the Association for the Advancement of Science, which was a major player in the March for Science in 2017, has not endorsed this march at all.

FLORA LICHTMAN: What came of that one? What’s different about this one?

ANIL OZA: Yeah, so I think, taking a step back, we’re in a very similar moment to 2017. There is a lot of pressure on scientists. They feel like they’re under attack. Trump is having this sort of same rhetorical attack on scientific institutions, on universities. There’s threats to funding. He’s putting appointees that eschew the scientific consensus.

And so, in 2017, scientists, right as Trump first took office, sort of said, enough is enough, we need to take to the streets. And so they planned this March for Earth Day in 2017. They had, by their own estimates, about a million people in 650 marches on every continent across the globe. It was this really watershed moment because scientists don’t really like to engage in political activities.

And after that march, which was huge, they formed this nonprofit, which was around for a couple of years. They were around into the next election cycle in 2020. But they definitely had diminished influence. They didn’t really know how to run a nonprofit. There was definitely clashing ideas of what they should be focused on. And so they kind of petered out.

FLORA LICHTMAN: I’m hearing drama.

ANIL OZA: Absolutely, which is very common in activist groups and in nonprofits. But I think it was disappointing to a lot of people that went out in 2017 and wanted to see this movement sustained. And while the organization March for Science did not last, I think its effects can be seen in the fact that it did seed a generation of scientists that are activists. And it did change this ethos of political engagement and science communication among scientists.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Wait, say more about that.

ANIL OZA: Yeah, so historically, scientists don’t love to engage in politics. There’s this image of a scientist in their lab completely separated from the rest of the world. And scientists would go back and forth about this all the time, about whether they should engage in politics directly. And 2017 kind of shut the door on that. It said that, yes, we need to be out in the streets.

We need to be engaged. Otherwise, there will be attacks on science. And so that really fundamentally changed this conversation. And obviously, scientific activists would argue for the better, that it enabled scientists to go out into the streets. And I think an event like the one that we are about to see today would not even be thinkable if it was not for the March for Science in 2017.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Anything you’ll be keeping your eye on as you cover this today?

ANIL OZA: Yeah, absolutely. I think the first thing is just crowd size. I think it’ll be really interesting to see how many people show up. Like I said, we are in a moment where the temperature is very high, where scientists are losing jobs or losing funding. They are very upset.

And I’ll be keeping an eye to see if that does translate to crowd size. We are obviously, today is a Friday, so we may not get as many sort of casual people that just support science out in the streets. But then going forward, I want to see if it does nudge these bigger players to step into the field. This is being put on by mostly early career researchers.

So I think the real thing is to keep an eye on is, going forward, do universities, scientific societies, university presidents, these big wig scientists, and eventually politicians step into the fray to also defend science to buy into some of the notions of this march and really step against the Trump administration in its funding cuts and all these other attacks on the scientific process that they’ve enacted over the past about a month and a half.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Thanks for joining us today, Anil.

ANIL OZA: Absolutely. A pleasure to be here.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Anil Oza, reporter for STAT at MIT, based in Boston, Massachusetts. We put out a call to listeners to find out whether you were going to the march, and we got a huge response. So we’ve got two young scientists on the line to tell us why their Bunsen burners are on 11 for this, and why they feel like they have to be there.

Mike Wong is a planetary scientist and astrobiologist marching in Washington, DC, and Emily Reed studies environmental sustainability at the University of Louisville. She is attending the rally in her hometown of Frankfort, Kentucky. Thank you for joining us.

EMILY REED: Happy to be here.

MIKE WONG: Yeah, this is a real honor.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Well, we are happy to have you. Why did you feel like you needed to be at this rally? Mike, let’s start with you.

MIKE WONG: Yeah. I’m an early career scientist whose salary comes completely from federal funding. And with the sudden cuts to federal funding for science and the fact that it seems like the entire scientific infrastructure in the United States is crumbling all around us, I felt that it was really necessary as a practicing scientist and as somebody who helps mentor up and coming scientists that we need to speak out.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Emily, are the changes that are happening in science right now, the changes to funding, making you rethink going into science?

EMILY REED: A lot of people in my school and in my generation are very worried about what their futures are going to look like. That doesn’t mean that they are shaken in trying to strive for that world. But it does mean that we are anxious and are just kind of– yeah, we’re worried and stressed out.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Wait, tell me more about that stress. Unpack it for me.

EMILY REED: We’re worried about the industries we’re going to go into. We are worried about the budget cuts that are currently happening and how that is going to affect not just us personally, but also the world at large. With the NIH funding that is getting halted or delayed, with the delays in grants that are being given out across college sectors, that is going to slow down research or even stop research in certain areas with the certain censoring that’s happening.

People aren’t going to be able to ask the questions and do the research that they want to do to make the world a better place. So not only are my generation very worried about their jobs on the personal level in the future, but also just what the world in the future is going to be like versus the world that we grew up in or that we thought we were going to get.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Mike, what about you? Do you feel the stress?

MIKE WONG: Absolutely. And it’s honestly so heartbreaking to hear that stress pervade all the way down to Emily’s generation as well. It just feels like doors are shutting right in our faces and the opportunities are dissipating, evaporating right in front of our eyes.

And Emily’s absolutely right. Science is both a personal endeavor in terms of trying to get a career in science as an individual. But the ramifications extend all the way up to the planetary scale.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Does it make you rethink your path in science?

MIKE WONG: I love coming to work every single day. And I can’t imagine doing anything else. But it makes me hesitate about what’s going to come down the road in a year, in two years.

As a postdoc, I’m still seeking a permanent position, a job like a tenure track faculty position or as a civil servant working for NASA, for instance. And it just seems like those avenues are dwindling. And I’m not sure what the future holds. And I’m very anxious about it.

FLORA LICHTMAN: One thing that really strikes me about this is that I don’t know that taking to the streets is the natural state for many scientists. And in covering science for decades, I’ve heard from many scientists that you can actually be penalized for speaking out, for being a public figure. Does it feel significant to you that you’re seeing this swell of interest from scientists to get out there and raise their voice?

MIKE WONG: I think you’re absolutely right, Flora. We scientists, we like to stay in our labs, do as much research as possible, uncover the mysteries of the universe. And so this feeling that we need to be galvanized as a community to go and march in state capitals around the country and in Washington, DC really does speak to, I think, the dire nature of the situation.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Before we let you go, what’s on your poster boards?

MIKE WONG: [LAUGHS] Great question. I made a poster today with one of my favorite quotes from Mr. Spock. It says, “insufficient facts always invite danger,” from the Star Trek original series episode “Space Seed.” The reason why I chose that quote is because I want to stand up for evidence-based policymaking.

We need facts to guide the way that we act in the world, both for human health, for environmental justice, for everything. Because without facts, we’re really just in the dark with regard to what the consequences of our actions are. And so I think science really gives us a way to move forward and build that prosperous future that I think we all want to see. And if we cut off science funding, it will be very hard to accomplish that.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Emily?

EMILY REED: First off, you are so cool.

[LAUGHTER]

MIKE WONG: Oh, thanks.

EMILY REED: My poster board says, “research equals investment.” With the whole idea that a lot of this stuff is happening because it’s not efficient somehow, I wanted to do something against that and say that it is an investment for the future. You need to put aside some amount of resources for investing, for research, for science, so that, in the future, things can be even better or more efficient.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Thank you, both.

MIKE WONG: Thanks, Laura.

EMILY REED: Thank you.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Mike Wong, planetary scientist based in Washington, DC, and Emily Reed, student at the University of Louisville based in Kentucky. And thank you to everyone who called and texted us. We read and listen to every single message, and we so appreciate you sharing your stories with us.

Copyright © 2025 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

Flora Lichtman is a host of Science Friday. In a previous life, she lived on a research ship where apertivi were served on the top deck, hoisted there via pulley by the ship’s chef.