The Exotic Life Above The Forest Floor

17:44 minutes

Forest ecologist Nalini Nadkarni pioneered the exploration of tree canopies—the “new frontiers” of the forest, using hot air balloons, rock climbing gear, and cranes. There, high in the trees, she found soil coating the branches, much like the soil on the forest floor—and unique adaptations, like the water-gathering abilities of spiky bromeliads.

[The first major underwater film starred—you guessed it—a giant mechanical octopus.]

In this segment, recorded live at the Eccles Theater in Salt Lake City, Nadkarni takes Ira on a tour of the forest canopy, talks about how fashion can be a tool for science communication, and describes her work communicating science to underserved populations, like inmates in prisons around the nation—from minimum security to Supermax.

Nalini Nadkarni is a professor of biology at the University of Utah.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow, coming to you from the Eccles Theater in Salt Lake City.

[APPLAUSE]

If you’ve ever hiked through a rainforest, you’ll notice there’s a lot of stuff that looks like it’s just sprouting from the trees, a hanging garden of orchids. Or you got spiky pineapple-looking things. And of course, there are always ferns. What’s it all doing up there when the soil is down here underfoot? What about nutrients and water? How does a plant get food up on a tree limb?

My next guest has spent her life exploring these exotic worlds overhead, pioneering new ways to get up there, too, wish is slingshots, rock climbing gear, cranes, and hot air balloons. And she’s come back down here to earth to talk to us and tell us about that last frontier, the forest. Nalini Nadkarni is a professor of biology at the University of Utah here in Salt Lake City. Welcome to Science Friday.

NALINI NADKARNI: Thanks. University of Utah!

[APPLAUSE]

Go Utes! Is that right? Yes. Go Utes!

IRA FLATOW: Tell us what it is that fascinates you so much about the canopies of the trees.

NALINI NADKARNI: Well, you know, in keeping with the theme of tonight, this new frontiers idea, I guess I have to say there are really three reasons why I find the canopy so fascinating and why I’ve spent the last 35 years climbing up there and trying to understand what’s going on up there. One of them is just– it’s about trees. And just as some people are attracted to the sky or to the stars, I’ve always been attracted to trees.

They’re like us. We have crowns. They have crowns. We have limbs. They have limbs. We have trunks. They have trunks. So it’s really the trees. But it’s also the climbing of trees, which I’ve loved to do ever since I was a little kid, just getting up there with my grasping hands and my binocular vision, which evolved to really make us comfortable, which made us feel at home in the canopy.

And I guess the third reason is really because it has been the last biotic frontier. And I think it’s the job of everyone in science, whether you’re doing research or learning about it or teaching eighth graders about science, to find and discover new things. And the canopy really has not been much explored. So those three things attract me to the canopy.

IRA FLATOW: And you’ve had to invent a lot of new ways to get up there, right? Tell us about some of these things that you’ve been inventing.

NALINI NADKARNI: Well, there’s the old-fashioned way of climbing, of course. But when you climb into rainforest trees, which are very tall, very often they don’t have lower branches, very often they have stinging insects or thorns, it’s important to avoid those things by getting ropes into the canopy.

I learned from a biologist named Don Perry who used a crossbow to first shoot a line into that. But I was working in Costa Rica. And so when I would carry my crossbow in the luggage across international borders and said that this was a scientific instrument, I met with some skepticism. So I actually invented an instrument to get that first line into the canopy called a Master-Caster.

IRA FLATOW: You have one with you.

NALINI NADKARNI: I did bring it tonight, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s look at it. From the Master-Caster, ladies and gentlemen. Look at that.

[APPLAUSE]

For our players at home, let me describe it. It’s got a fishing casting reel on it, right?

NALINI NADKARNI: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: It looks very much like one. How is it different?

NALINI NADKARNI: Well, it is a fishing reel. It’s actually just a rod. It’s about a half a meter long with a fishing reel underneath it so you can retrieve the line. And then the feature that’s most important, of course, is the strong slingshot that actually you can buy at any Army-Navy store.

And so what I do is there’s a two-ounce fishing weight here at the end of the line. The idea is to simply hold the fishing weight. You take off the bail right here. You load up the slingshot. So this really gives you the power to move the weight and the line up and over a first branch.

You then tie a parachute cord, a quarter-inch nylon, pull that up and over. And then you can tie a regular climbing rope and pull that up and over, tie one end of the rope off of that. And after that, you just put on climbing gear you would get at REI. You jumar up the rope.

It’s safe. It’s nondestructive to the tree. When you’re done doing your studies up in the tree, you just pull the rope down. And there you are.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. It’s great.

[APPLAUSE]

Now, as someone who raises orchids, I’m always looking at them growing wild in trees. I go to Costa Rica, where you’ve–

NALINI NADKARNI: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, you see them all over the place. How do these plants that live up in the canopy– how do they get the nutrients that we would normally do fertilizing them if they lived in the ground? How do they live up there?

NALINI NADKARNI: So these plants, they’re called “epiphytes,” “epi” meaning “upon,” “fight” meaning “plant.” They don’t have roots that grow into the host tree tissue, the vascular tissue, nor do they go all the way down to the forest floor.

But instead, these plants– and they are enormously diverse. Just orchids alone, 28,000 species of these have evolved ways to capture nutrients from rainfall and mist and just dry deposition, dry particulates falling down. Some of them have tanks that allow them to absorb water from their little ponds. Others have foliage that allow them to take up nutrients through the leaves rather than roots.

And these plants then intercept, retain, hold onto those atmospherically borne nutrients. When they die and decompose, they stay right there on the branch. And they create actually this just fascinating stuff, this canopy soil, that can be 20, 30 centimeters deep. And you want to know something really cool, Ira?

IRA FLATOW: Always, always.

NALINI NADKARNI: OK. I know you do. I know you do. When I was a graduate student working in the temperate and tropical rain forests of Washington State and Costa Rica, I was peeling back these mats of living epiphytes and that dead organic canopy soil that was on the limbs. And I found these root systems up high in the canopy. I thought, where the heck are these coming from?

So I traced them back. And it turned out these root systems originated in the trunks and the branches of the host trees themselves. So these canopy plants were generating a soil. The trees are putting out roots into these massive, dead organic matter, absorbing water and nutrients. So it was kind of a shortcut in nutrient rainforest cycles. And that was really cool.

IRA FLATOW: Mind blown.

NALINI NADKARNI: Yeah.

[APPLAUSE]

IRA FLATOW: As someone who raises plants and likes to look at plants and the different ways that they grow, I notice that some plants are able to collect water. And they can collect water, and they use that as their source of water.

NALINI NADKARNI: That’s right. So one big plant family that is epiphytic, the Bromeliaceae– actually, as you mentioned, the pineapple family have these tight rosettes of leaves. Water falls onto them from rain. Leaves fall into them, decompose.

They create really their own little microcosm, their own little ecosystem. And there are trichomes, or hairs, that go into that little pond. And the leaves can then absorb water and nutrients from their own little ponds.

IRA FLATOW: And so what happens– unfortunately, some of those plants up in the canopy die.

NALINI NADKARNI: Yes, they do. They do die.

IRA FLATOW: Well, that’s the cycle of life, right?

NALINI NADKARNI: Yes, that is the cycle of life.

IRA FLATOW: What happens to them? Do they fall down? Do they contribute to the nutrients for the other plants?

NALINI NADKARNI: That is also a great question. And that’s some work that we did sort of mid-career, where we noted that these epiphytes sometimes would fall down individually. Little bits of them might fall down.

Sometimes they– what I call “epislides.” They’re like little avalanches of whole mats of epiphytes that fall to the forest floor. And we would monitor these over the months and found that they experienced something that we called “moss meltdown,” where they would just decompose and disappear very rapidly. So there’s something about the canopy environment that allows these massive organic matter to persist.

But when they fall to the forest floor– which is, of course, wetter, damper, might have other microbial communities– they decompose. And their nutrients then are available to the terrestrially rooted materials. So epiphytes are really– although it looks and it seems like there’s this own little world up there, they’re actually deeply connected to the forest as a whole. And that to me is really wonderful, too,

IRA FLATOW: That’s very interesting. If you want to ask a question, you can step up to the mic. Question over here? Yes.

AUDIENCE: How do the trees or the new plants underneath the trees get enough sunlight to grow? Or do they just all die off until another tree falls or breaks down to get sunlight?

NALINI NADKARNI: Yes, that’s a very interesting dynamic in tropical rainforests. Because trees are so big, the canopy levels are so layered, there’s very little sunlight. Sometimes only as little as 2% of the sunlight that comes into the top of the canopy reaches the bottom of the forest floor. And so very often, there’s a dynamic where it’s important and necessary for trees to fall down to create a light gap that allows the next generation of rainforest plants to germinate, to grow, and to survive.

IRA FLATOW: I want to ask you something not about what you study, but what you’re wearing. That’s a terrific jacket.

NALINI NADKARNI: It’s a terrific jacket. Actually, I was in the lobby, and several people came up to me. And they said, wow. I like your jacket. And that is exactly the point of this jacket. This is a new item called “nature wear.”

IRA FLATOW: Describe it for us.

NALINI NADKARNI: Yes, I will. First, it’s a smart-looking little jacket. It has patterns of leaves on it, leaves and light. And it’s green.

IRA FLATOW: It’s green green. It’s very green.

NALINI NADKARNI: It’s a bright green color, not something a lot of people wear to a formal occasion. But in my case, what I’m using this jacket for– and more generally fashion. I’m exploring this– is the possibility of using fashion to enhance conservation, to raise awareness of tropical rainforests. So the pattern that you see here is–

[APPLAUSE]

It’s actually a photograph I took of a plant called “Piper auritum.” It’s related to Piper nigrum, which is the plant that makes black pepper. It lives in the tropical Montaigne forest of Costa Rica, one of the most threatened ecosystems by climate change because of the loss of mist and fog as temperatures go up.

So I took this photograph. We had it printed on fabric. I worked with the costume designer at the University of Utah. We brought in a tailor, and we created this.

But what’s most important is when someone like you, Ira, says, I really like your jacket. There’s also a hang tag here, which has information about Piper auritum, the fact that it is, in fact, related to Piper nigrum, the black pepper that you put on your scrambled eggs.

[APPLAUSE]

IRA FLATOW: You know, this is fantastic because one of the things we always talk about is scientists as communicators.

NALINI NADKARNI: Yes, that’s right.

IRA FLATOW: This is an absolute great demonstration of great science communication.

NALINI NADKARNI: And I think, too, what is also important is that we have information here about joining the Rainforest Alliance and other conservation groups. So this is something that anybody who wears this nature wear becomes a walking vector not only for education, but conservation.

And I think it’s sort of hilarious that ecologists, who are probably the worst-dressed people in the nation, might intersect with an industry– the fashion industry– that we view as being the most consumeristic, the most wasteful, the most polluting. But in fact, I think we as scientists have to look everywhere for ways that we can create opportunities to spread our scientific knowledge and the deep importance of conservation.

[APPLAUSE]

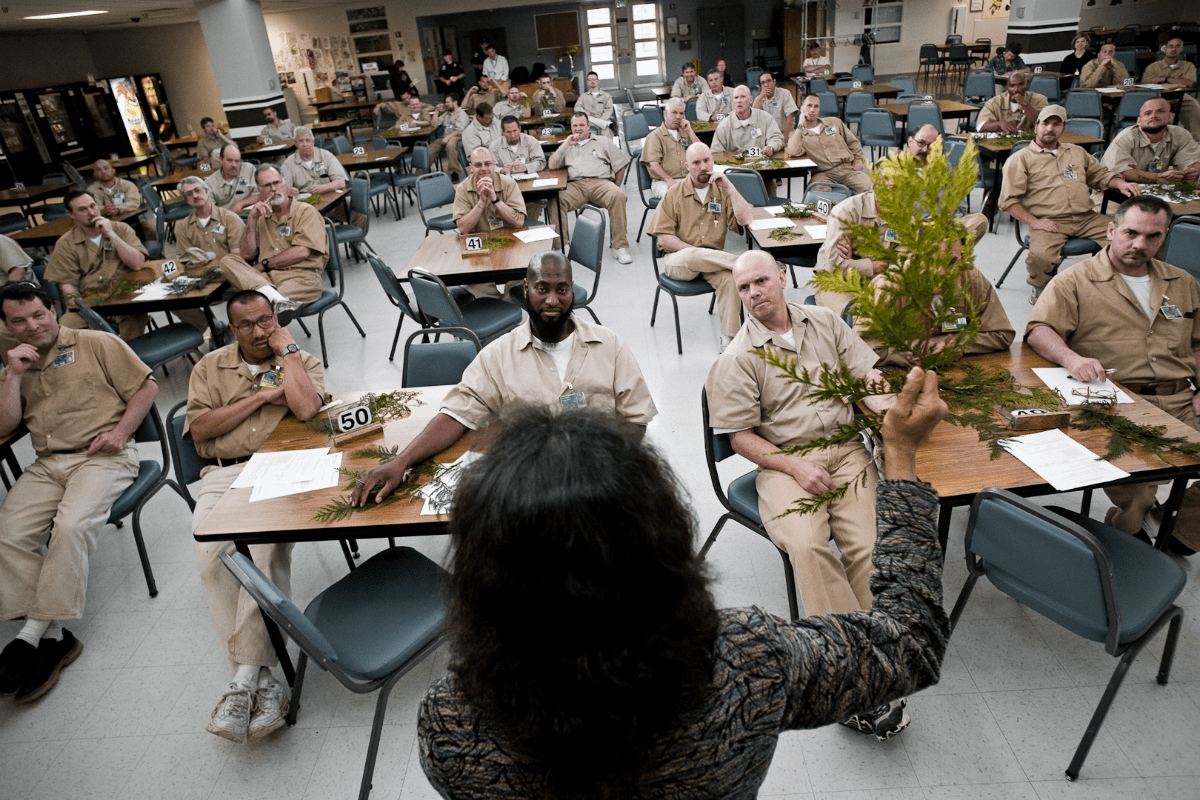

IRA FLATOW: And in spreading that and in creating that deep conversation, you take that conversation I understand into prisons, too, correct?

NALINI NADKARNI: Yes, I do. This actually was an idea that grew out of an ecological problem that concerned epiphytic moss. I was living in the Pacific Northwest.

I learned that there is an industry on secondary plant materials, where people go out to the old growth forests of the Pacific Northwest and just grab mosses from branches and trunks of trees in the old growth forests, which they then sell to people in the horticulture trade, the florist trade, and so forth. And as our research has shown, this moss takes a very long time to grow back– two, three, four decades. So it’s not a sustainable industry.

So I thought, well, if I could learn how to farm mosses, maybe that would take some of the pressure off of this wild collecting. So I wanted to learn how to grow mosses. I didn’t have any students or a greenhouse at the time. And I began thinking, who would be great partners in this, people who would really enjoy and benefit from contact with nature, maybe people who don’t have access to nature, people who have a lot of time and a lot of space?

And it occurred to me that probably the incarcerated men and women and youth of our country, of which we have 2.2 million and 100,000 youth who are incarcerated– they might be exactly the right partners. And it turned out that that was the case.

My students and I brought mosses to a small minimum security prison in Washington State. We taught the men how to tell the species apart. And they helped us learn which species of mosses grew the fastest. And that led to other conservation projects, other educational projects.

[APPLAUSE]

It was pretty cool. We started programs five years ago here in Utah. So we have a science lecture series and conservation project at the Draper State Prison just 30 miles south with the Salt Lake County Jail. And now recently, we just got some funding from the Juvenile Justice Service. So we have five juvenile detention centers where we’re bringing science lectures and conservation projects. That’s been really fabulous.

[APPLAUSE]

IRA FLATOW: Amazing. I’m Ira Flatow, and this is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. Do you follow up with the prisoners to see if it affects their lives at all?

NALINI NADKARNI: We get a lot of information from the men and women and youth who are inside. It’s very difficult to follow up over the long term. Basically, once they’re off parole, they’re really on their own. And even the Department of Corrections can’t contact them.

But we do get information every now and then, a letter or a visit from one of these inmates who has been released and has since found work with landscaping. One of them actually has gotten his PhD and has done a post-doc at the University of Nevada inspired by the work that he encountered with us. So I think that’s–

[APPLAUSE]

But you know, Ira, I think even though that’s a big impact, and even though that sounds really wonderful, I think really the biggest impacts are on the scientists who go into the prisons and into the jail, who have the opportunity to interact with inmates, to hear their good questions, to recognize that this is a group of people who are as interested in science as you are and who may not have the opportunity to go to a library, go to a museum to learn.

But when you present them with science as well as you can with a single lecture from a graduate student or a faculty member in the Department of Biology, for example, at the University of Utah, that spark of science, that feeling of curiosity, that desire to penetrate a new frontier is present in those men and women and youth just as it is in people who aren’t incarcerated.

IRA FLATOW: Very, very interesting.

[APPLAUSE]

I see our audience is interested, also. They’ve lined up at the mic. Yes, sir?

AUDIENCE: How do these seeds or spores or whatever– how do they take root in the canopy in the leaves or the trees or whatever?

NALINI NADKARNI: How do they take root?

AUDIENCE: Yeah.

NALINI NADKARNI: Yes. There are a couple of ways. In many, many canopy plants, such as orchids, which Ira is very, very interested in– these orchids produce millions and millions of what we call “dust seeds.” They’re just tiny, tiny, tiny, tiny seeds.

They flow through the air almost like pollen. And they can settle on branch surfaces or trunk surfaces. If the conditions are right, if there’s enough moisture, if the proper fungus is there– usually they require a fungus, especially orchids– then those plants can germinate and take place.

Mosses, for example, use a different kind of strategy. Very often, they break off little pieces of them. And those can sort of flow through the air or fall around. And those little bits of mosses can get stuck in a crevice of the bark. And then they can take off as well. So the germination and the survival of these plants is very similar to what we see with plants on the forest floor.

But if you think of where is a safe spot for a new plant to take place, you don’t have the forest floor, which is a two-dimensional plane where a seed can land anywhere. You have these tubes, these cylinders of branches in three-dimensional space. And in between that space is not a safe spot. So actually finding the right safe spot and germinating there is really much more of a challenge for these canopy-dwelling plans than those not quite as interesting plants on the forest floor.

IRA FLATOW: Nalini, this has just been fascinating. Thank you so much for coming out.

[APPLAUSE]

Nalini Nadkarni, professor of biology at the University of Utah here in Salt Lake. Thank you again for taking time to be with us today.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Taking us to the break, our musical guests for the evening, Salt Lake City’s own The Boys Ranch. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christopher Intagliata was Science Friday’s senior producer. He once served as a prop in an optical illusion and speaks passable Ira Flatowese.