The First CRISPR-Edited Babies Are (Probably) Here. Now What?

19:45 minutes

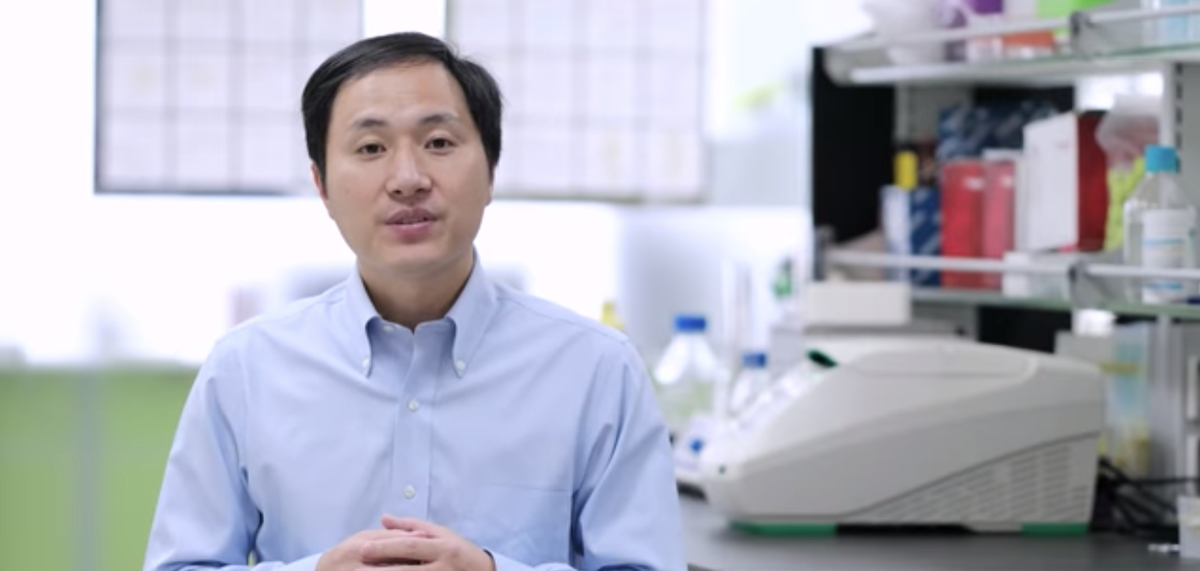

This week, Chinese scientist He Jiankui claimed to have created the first CRISPR-edited babies, disabling the CCR5 gene that plays a key role in HIV infection. The twin girls were born earlier this month.

Many scientists in the field say this oversteps the ethical bounds of gene editing technology. The Chinese government halted research in this area, and the Second International Summit on Human Genome Editing committee released a statement that said “it would be irresponsible to proceed with any clinical use of heritable ‘germline’ editing at that time.” Bioethicist Josephine Johnston and geneticist Paula Cannon, who researches using gene editing as a therapeutic for HIV, talk about what social, ethical and regulatory questions scientists and society discuss as gene editing technology progresses in the future.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Paula Cannon is a Distinguished Professor of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology in the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, California.

Josephine Johnston is a bioethicist and the Director of Research at The Hastings Center in Garrison, New York.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. This week, a Chinese scientist made a stunning announcement. He claimed to have used CRISPR to edit the genome of embryos to alter a gene that plays a role in HIV infection. And then twin girls were born earlier this month from these embryos, and there may be more babies.

The Chinese government halted research in this area. And the committee of the Second International Summit on Human Genome Editing, which happened this week in Hong Kong, released a statement that said, quote, “it would be very irresponsible to proceed with any clinical use of heritable germline.” Is this tagging CRISPR too far?

What are some of the ethical, social, and regulatory ideas that we should be thinking as gene editing technology moves forward? Where would you draw the line with gene editing? What questions do you have about CRISPR and what it can do?

We want to hear from you. Our number, (844)724-8255. That’s (844)724-8255. You can also tweet @SciFri.

That’s what we’re going to be talking about with my next guests. Josephine Johnston is a bioethicist and director of research at the Hastings Center in Garrison, New York. Welcome to Science Friday.

JOSEPHINE JOHNSTON: Thanks for having me back.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome.

JOSEPHINE JOHNSTON: Paula Cannon is a professor of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology at the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. Welcome to Science Friday.

PAULA CANNON: Hello, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: And as I say, our number (844)724-8255 if you would like to chime in. Paula, the scientist doctor, he did not publish a study or show the data. So right now it’s still a claim. But you think he actually did gene edit these kids?

PAULA CANNON: I think so, yes. Certainly from the data he’s presented, if one assumes he isn’t falsifying anything, it looks pretty compelling to me that he has done what he’s claimed to do. But of course, I’m going to wait to see the actual data when he submits it and indeed when it gets published. But I think most people would probably think that he has done what he’s claimed to do.

IRA FLATOW: Josephine, CRISPR hasn’t been around for that long. Were you surprised that this happened?

JOSEPHINE JOHNSTON: Not that it happened at all. But I wasn’t expecting it to happen this week or even really this year. So it does seem like the kind of thing that certain people are going to want to try to do. But I hadn’t been expecting it yet because the safety questions do seem rather large and that makes using it to create children seem quite risky.

IRA FLATOW: Well, let me ask you about that because what line was crossed here? I mean, because this type of research being done in embryos is done all the time. What was the line, the ethical line that was crossed?

JOSEPHINE JOHNSTON: So there has been some research using CRISPR in human embryos but not embryos that were then transferred to a woman’s body for gestation and birth. They were in a lab. They were laboratory research. And this is, as far as I know, the only time that anyone has actually taken the embryos that have been edited with CRISPR and actually tried to generate a pregnancy out of them. And there’s no other known cases of it in the public domain. And so they were really two lines crossed, at least.

One is that pretty much everybody that I’ve heard comment on this agrees that one of the lines is that he prematurely leaped into a clinical use to create babies. So that that’s like just going far too quickly. And you said how far should we go with CRISPR? But the other question is how fast? And he prematurely moved into clinical research. And most people I’ve heard comment agree about that.

The other line is a little different. And the other line is doing what’s called a germline change, so making a change that can be inherited, that can be passed on generation to generation. And that’s another line in the sand that a lot of people and a lot of countries actually think it should not be crossed. And so that’s the sort of second way in which this was big news.

IRA FLATOW: Well, let me ask Dr. Cannon, why would he cross that line? And if no one else was doing it, why would he do that?

PAULA CANNON: Oh, gosh, you’d have to ask him, wouldn’t you?

IRA FLATOW: Yeah.

PAULA CANNON: I think the line that he crossed, I think I want to stress that it wasn’t really that much of a technical line. This sort of embryo editing using CRISPR had already been demonstrated in multiple different animals, including producing edited monkeys, for example. And we’d already seen that people had developed the technology to edit embryos that had not been transplanted.

So the technical line that he crossed, if you like, was a relatively small step of then taking those edited human embryos and implanting it into a woman. Why he chose to do that, having listened to his explanation, he really seems to think that he’s doing something for the good of humankind, that he’s trailblazing, that this needs to be done. And he is demonstrating, in his mind, I think, that this can be done safely.

IRA FLATOW: But we won’t know if it’s safely done, do we?

PAULA CANNON: Absolutely not. No, absolutely not. There’s a number of things to consider when you think about safety, first of all, the technology. The goal is to change, in this case, one gene.

But we know that although CRISPR can be highly accurate, it’s not 100% accurate. And so there is always the risk that there will be other genes that are by accident changed at the same time. And we don’t know what the consequences of those could be. And in addition, he chose this gene CCR5 for what I think were very not convincing reasons. And I think one of the reasons he chose that is because certain people, about 1% of the population, mostly Europeans, naturally don’t have this gene.

So the idea that he could knock it out or destroy it in these embryos, he would argue that that was an innocuous change. But I really think that that has not been definitively shown at all. So on a number of levels, the safety really was not yet demonstrated.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Johnston, would you agree?

JOSEPHINE JOHNSTON: That is my understanding. I’m not a scientist or a clinician. So assessing the safety is not my forte. But everything I have heard says the same thing. And I actually had a question for Dr. Cannon because I also heard that people without CCF5 are more susceptible to the flu. Is it true? And if so, that makes the trade-off even more less convincing.

PAULA CANNON: Yeah. No. That’s definitely some consideration about what not having CCR5 might do to you. While it’s clearly associated with being profoundly, although not completely resistant to HIV, which was the positive attribute, if you like, that Dr. He was going after, this is a molecule that’s important for a lot of the way that our immune system responds to viruses. And for example, people who naturally don’t have CCR5 are much more likely to have a bad outcome if they’re infected with certain viruses.

The most significant one that I know of is West Nile virus, which most of the time causes an asymptomatic infection. But people who don’t have CCR5 are much more at risk of having very devastating neurological complications from this disease. And certainly I’ve also heard the flu story. Although I think that’s only been demonstrated really convincingly in mice that have been engineered not to have CCR5.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Cannon, what are the guidelines in place here in the United States right now about using CRISPR in embryos?

PAULA CANNON: Sure. So there’s multiple levels where this is regulated. The United States, along with many nations, has just guidelines in general about how you could do any sort of experimentation, if you like, on humans at any stage of their life. And when we have even new drugs or new therapies, you, first of all, have to get approval at multiple levels.

First of all from the FDA and then secondly within your own institution, there will be a board referred to as the Institutional Review Board, which is typically a group of clinicians and scientists and members of the community that also evaluates whether what you’re doing is safe and appropriate. And with a special case of doing any sort of genetic manipulation, including gene editing, the United States also has a review body called the Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee that looks at this, so multiple, multiple levels.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Johnston, can you get international consensus on any of these guidelines?

JOSEPHINE JOHNSTON: Well, so it depends how many countries you want in your group in order to say you have it. But there’s been a good amount of international consensus on research ethics on how to do research in humans and what the appropriate safeguards need to be. I think that the summary statement from the summit that just happened in Hong Kong, which is the second, first summit being in DC In 2015, that’s a consensus statement essentially from those groups. And they’re representing three countries. And they, I’m sure, don’t agree on everything. And even in the document they note that different countries will ultimately probably want to have some of their own specific rule.

But they’re certainly pretty clear that they all agree that the work is not able– you shouldn’t be doing this kind of germline gene editing just yet. And I wanted to add that the US government and the Congress actually has actually passed a piece of– it’s a budget rider that was passed first in 2015 but has been passed since that prohibits the FDA from looking at any application to do clinical work that would result in inheritable change. So that would cover this kind of study. And so as Dr. Cannon said, you would have to go to the FDA if you wanted to do this kind of experiment in the United States.

But Congress has actually prohibited the FDA from looking at those or from entertaining. So you couldn’t get permission right now. It would actually be against the law.

IRA FLATOW: I have a quick tweet I want to get to before the break, about a minute. Adam writes, “as a type-I diabetic, if gene editing had been around when I was conceived, I wouldn’t be suffering today.” How do you answer that?

PAULA CANNON: Well, that’s not strictly correct, I would guess, because type-1 diabetes was still not sure what triggers that in many cases. So it would be really hard to sort of make a change into an embryo to make you resistant to that. However, there are lots of other potential new types of therapies that are being developed to treat type-1 diabetes that use gene therapies and cell therapies. So there’s some positive things, I think, coming down the line that can treat people who have type-1 diabetes. But the idea that we could predict this at the embryo level and make changes to protect us is not correct–

IRA FLATOW: All right.

PAULA CANNON: –sadly.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. We’re going to take a quick break and talk more about this when we come back with my guests, Josephine Johnston, bioethicist and director of research at the Hastings Center in Garrison New York; Paula Cannon, professor of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology at USC in Los Angeles. Our number, (844)724-8255. We’ll take your calls and more tweets. I don’t want to use the Christmas tree analogy, but the board is lit up. We’ll be right back after this break.

This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. We’re talking this hour about using CRISPR gene editing to alter embryos. My guests are Josephine Johnston and Paula Cannon. Our number, (844)724-8255. Let’s go to the phones. Let’s go to Denver. Alex in Denver, hi, welcome.

ALEX: Hi, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Hi there. Go ahead.

ALEX: So, yeah. So my question is regulatory issues aside, if we could imagine a future where this is assumed to be ethically OK, why is that future not here yet? Like, what are the ethical issues around the timing of this that need to be addressed before we could reach that future state, since there’s a lot of excitement about it?

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, good question. Dr. Johnston, you want to tackle that?

JOSEPHINE JOHNSTON: Well, the big issues are safety and efficacy. Does it work, and is it safe and how safe is it? Because nothing’s usually 100% safe. But the other big question, I think, is this question about whether or not it’s appropriate to make permanent changes to future persons’ genomes. And if it is appropriate, is it appropriate to make any kind of change whatsoever? Or are there only certain kinds of things that ought to be changed? And the kinds of things that people might argue is that we should just make changes related to lethal conditions or very serious genetic diseases.

Some people would like to see some disabilities but not others be subject to this kind of editing. Other people are really looking forward to being able to edit genes associated with tiny increases in IQ or height or athletic ability, controlling eye color, et cetera. So none of those– the scope of the appropriate targets, even if we could do those things, the scope how, appropriate it is, and how much social– how much leeway to give to prospective parents versus how much to control at a regulatory or legal with legislation, those are all questions that haven’t been worked out.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Cannon, any comment?

PAULA CANNON: Yeah. And I actually think that the gene that was chosen in this case, the CCR5 gene, is really a perfect example of how the choice of the gene and the appropriateness of it is really in the eye of the beholder. Dr. He claims that he disrupted the CCR5 gene because this would give these little girls the ability to be resistant to HIV. And he seems to think that that’s an appropriate thing to do.

Whereas, I think a lot of people would argue that there are much easier ways to prevent yourself getting infected with HIV. We have safe sex. We have drugs people can take. That really this was like a sledgehammer approach to do something. So I think he’s maybe inadvertently created almost like a perfect textbook example of the complexities around discussing what would be appropriate uses of this technology.

IRA FLATOW: And how do those discussions happen?

PAULA CANNON: [CHUCKLES] Gosh. So again, the main people, sort of, discussing this right now and, I think, up to this point have largely been people in the community who are the gene editors. I’m not entirely convinced we’re the right people to be having these discussions. But certainly we understand the technology behind it.

Even the, sort of, international summit that’s going on this week and the prior statements from the national academies tend to come from people who are experts in the technology. And you could argue that we’re a slightly biased group, maybe one way or the other. I think the public needs to have a greater say in what should go forward. And one of the challenges there is how to help the public to understand the reality and the potential, including things that are not realities for this technology.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Johnston, you agree?

JOSEPHINE JOHNSTON: Yeah. Although, I do know that both at the summit and the national academies here, those panels had non-scientists on them as well–

PAULA CANNON: Sure.

JOSEPHINE JOHNSTON: –so people from, sort of, the bioethicists, actually, I wasn’t on the panels, but bioethicists and people from religious traditions or people who work in sociology or patient advocate. So it’s not just the science community. And in fact, one of the inventors of CRISPR, Jennifer Doudna, very early on, right after the initial papers were published, came out with a paper saying we can’t just have this conversation in the scientific community. This has got to be a more open conversation.

I think having that conversation at a granular level is difficult. But here we are right now having this conversation on the radio, so beginning some people talking about it and reading about it, people talking with students. So the Hastings– I ran a workshop this summer for high school science teachers to equip them to actually teach the stuff in their classes and to encourage their students to reflect. So there’s a lot of work to be done at multiple levels.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, because I have a tweet from– Carrie says, “I think CRISPR’s incredible. Someone had to take the risk. If both parents are well-informed and not being coerced, then I see no moral issue. I only have my own two incredible children thanks to the, quote, ‘miracle’ of science.”

JOSEPHINE JOHNSTON: So the one thing I wanted to say about that kind of– I really understand why people would like to leave these decisions with parents. And at the end of the day, I actually agree with that. But I want to note that we all know that there are many social pressures bearing down on people as they make decisions about this kind of thing.

So if you started to see a pattern, for instance, of American parents choosing genes associated with lighter skin color, you might think, oh, that’s just parents making their own free choices. Or you could understand that that’s a result of persistent racism in the country. So there really are social issues and cultural contexts that shape the kinds of decisions people make. And it’s important to also be addressing those in so far as they represent unjust situations. So I really value autonomy and individual decision making, but I want us to not forget that there are injustices and inequalities that can put a lot of pressure on people to make choices they might not otherwise make.

IRA FLATOW: Do you think that this news about this will open, begin a conversation like we’re having and make one a lasting conversation? Do you that’s going to happen?

PAULA CANNON: What I think–

JOSEPHINE JOHNSTON: I hope so.

PAULA CANNON: Yeah. And actually I think what’s interesting is to my mind it’s sort of shifted the conversation a little. Because up until this point, I think there was possibly a naive view that we could draw a line, that there would be a very bright line between applications of gene editing that might be appropriate– treating embryos from parents who are carrying an inherited genetic mutation, for example. But that other applications which are broadly considered personal preference or enhancement should not be crossed. And I think if anything, I’ve been thinking this week that now that the genie is out of the bottle, so to speak, it’s just completely ridiculous, I think, to talk about only having, sort of, therapeutic applications.

If this goes forward, even with the, sort of, best of intentions to treat truly terrible genetic diseases, then this is going to further develop the technology, make it safer, make it easier. And then I don’t see how you can draw the line at all.

IRA FLATOW: All right, we’re going to leave it there and come back to this very important topic. Josephine Johnston is a bioethicist, director of research at the Hastings Center in Garrison, New York; Paula Cannon, professor of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology at the Keck School of Medicine at the USC in Los Angeles. Thank you both for taking time to discuss this with us.

JOSEPHINE JOHNSTON: Thanks for having me.

PAULA CANNON: Yeah, thank you.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.