Finding Solutions To Treat Valley Fever

25:52 minutes

When you think of fungal infections, you might think athlete’s foot or maybe ringworm—itchy, irritating reactions on the skin. But other fungal diseases can cause much more serious illness. One of them is valley fever, caused by the soil fungus Coccidioides. In 2018, over 15,000 people were diagnosed with coccidioidomycosis, commonly known as valley fever, in the United States, mainly in the American West, and in parts of Mexico, and Central and South America. But the numbers could be much higher: The disease is commonly misdiagnosed and the hot spots are difficult to pin down. Plus, the endemic region could grow with climate change.

When you think of fungal infections, you might think athlete’s foot or maybe ringworm—itchy, irritating reactions on the skin. But other fungal diseases can cause much more serious illness. One of them is valley fever, caused by the soil fungus Coccidioides. In 2018, over 15,000 people were diagnosed with coccidioidomycosis, commonly known as valley fever, in the United States, mainly in the American West, and in parts of Mexico, and Central and South America. But the numbers could be much higher: The disease is commonly misdiagnosed and the hot spots are difficult to pin down. Plus, the endemic region could grow with climate change.

Science Friday digital producer Lauren Young takes us into the Central Valley in California—a valley fever hot spot—to learn more about how the disease spreads and the people it harms. She tells the story in a new feature on Methods, from Science Friday, using video, sound, and pictures, gives you a flavor of the challenges faced by scientists working to solve big problems.

Ira brings on Valley Public Radio reporter Kerry Klein, who helped us report this story, to tell us more about the communities valley fever is impacting and new treatments. He also talks with UCSF microbiologist Anita Sil to dig deep into fungal pathogens and the latest research.

See the full special report on valley fever on Methods, from Science Friday: sciencefriday.com/valleyfever

See the full special report on valley fever on Methods, from Science Friday: sciencefriday.com/valleyfever

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Kerry Klein is a reporter at Valley Public Radio in Fresno, California.

Anita Sil is a microbiology and immunology professor at the University of California, San Francisco.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. When you think of fungal infections, you might think athlete’s foot, or maybe ringworm; itchy, irritating stuff on the skin. But other fungal diseases can cause much more serious illness. Consider Valley Fever, caused by fungi in the soil.

In 2018, over 15,000 people were diagnosed with Valley Fever in the US, mainly in the West. Cases in Latin America too. And the numbers could grow with climate change. The Central Valley in California is a Valley Fever hotspot.

Science Friday digital producer Lauren Young took her microphone, her camera and recorders, and went to California; to capture the stories of the scientists and victims, to learn more about how the disease spreads and the people it harms. She tells the story in our “Methods” project, which using video sound and pictures, gives you a flavor of the challenges faced by scientists working to solve big problems. And you can watch the videos and read about her trip at sciencefriday.com/valleyfever. And Lauren is here to tell us more. Hi, Lauren, welcome.

LAUREN YOUNG: Hey, Ira. Good to be here.

IRA FLATOW: Tell me about the interest. What got you interested in the first place, in this story?

LAUREN YOUNG: I grew up just outside of Fresno, which is pretty much smack dab in the middle of the San Joaquin Valley. It’s one of the major hot spots for Valley Fever, and where the disease actually got its common name. But when I moved out here to New York, I realized a lot of people didn’t know about Valley Fever.

I first found out about it from my mom. She had gotten it when she was just a teenager. Many of my relatives worked on farms and fields throughout the Central Valley.

And so one summer she had been working on her uncle’s farm in Madera. And she’d been packing dried red onions. And she was just breathing in this dust flying out, from unloading bin after bin of onions. And after a week of that, she started to feel not so well. And so here’s how she described it.

PAM YOUNG: At first I thought maybe I was catching a cold. But it was like, hard to breathe. And I, when I would take a breath. I could hear a wheezing part. And then, I was really, really, really tired. And I was going, this is not my norm. And I didn’t know what it was.

IRA FLATOW: That was your mom, Pam, out in California. How is she doing now?

LAUREN YOUNG: She’s doing well now. She’s totally healthy. She got treated in time and recovered. But we also got so many listeners who just called in our VoxPop app, to share their stories.

AUDIENCE: I was affected by Valley Fever when I was four and five years old, 1945 to 1950.

AUDIENCE: When I was living in Tucson, 20 years ago, I contracted coccidioidomycosis.

AUDIENCE: In 1982, when we lived in Bakersfield, they went ahead and ran a blood test. And yep, I had Valley Fever.

AUDIENCE: My husband, Dusty, has Valley Fever he was diagnosed in 2017.

AUDIENCE: Late last year, my 83-year-old mother showed some kind of shadow, some kind of scarring in her lungs.

AUDIENCE: I was really lucky. All I had was a severe chest cold. But it felt like there was an anvil on my chest.

AUDIENCE: After more tests, including a biopsy, they found that what she had was a scar that resulted from Valley Fever.

AUDIENCE: It disseminated to his brain. And he has had four or five strokes and we moved to North Carolina, so his dad can help me take care of him.

AUDIENCE: There was a lot of new construction and dust in my neighborhood. I think that made it easier for the agent to get into people’s lungs.

AUDIENCE: I was told to get out of the Valley, so my grandmother and I went up to a family cabin in Yosemite, and spent the summer-winter there.

AUDIENCE: She lives in a Northwest suburb of Phoenix. Many of her friends have been, in the past, diagnosed with Valley Fever. It seems to be endemic to that region.

AUDIENCE: It’s an illness not very many people know about. But it can really have lasting effects.

LAUREN YOUNG: That was David, Marilyn from Boulder, Sue in Missouri, Rebecca from North Carolina, and Guillermo, talking about his mom in Phoenix.

IRA FLATOW: Now, tell me, are those typical symptoms of Valley Fever?

LAUREN YOUNG: Yeah, so the symptoms and outcomes of this disease can vary drastically from case to case. Some people just get a cough or a Fever. Some never recover. And some die from this disease.

And scientists and doctors are really trying to figure out why this is happening. So I spoke to some of those researchers, and to Art Charles, a patient in Bakersfield, California, who’s had Valley Fever turn his life upside down.

ART CHARLES: I used to be pretty athletic. [LAUGHS] I played basketball for the high school, won a state championship, got a scholarship to Boise State.

LAUREN YOUNG: Growing up, Arthur Charles lived and breathed sports. But today, Arthur, who goes by Art, is winded after just 30 minutes of talking.

ART CHARLES: If I talk a long time it just like, it just kind of just takes it out of you.

LAUREN YOUNG: Art is a Major League Baseball Recruiter in the city of Bakersfield, in the Central Valley of California. When he first got sick, the doctors assumed it was pneumonia. This was two years ago, well before the coronavirus took over our lives. He had been on a morning walk with his wife, when he started to feel unwell, then over a few days, he became short of breath, dizzy, nauseous, and extremely exhausted.

ART CHARLES: I didn’t have a drop of energy at all. I’ve never felt so weak and so beat in my life.

LAUREN YOUNG: At first, doctors gave him antibiotics. But that didn’t work, because Art didn’t have a bacterial infection. Eventually, they figured out he had Valley Fever, a disease caused by a fungus called coccidioides, or cocci, for short.

Cocci grows in the soil of dusty, dry regions, in the Southwest United States, Mexico, and Central and South America. To become infected, all you have to do is breathe. There are thousands of new infections in the United States every year.

Art’s family has been hit three times. Most people get flu-like symptoms, and recover on their own. But for about 40% of people, Valley Fever can regress into a more serious pneumonia-like condition, often misdiagnosed. If you catch it in time, you can usually treat it with antifungals and recover. Like Art’s son, who was infected in 2008.

But then, there are the 5% to 10% of cases, like Art, who develop chronic Valley Fever. Where the fungus just keeps growing back. And in an even smaller percent, about 1% of cases, the fungus can be deadly. That’s what happened to Art’s older sister, Deborah, who got sick when Art was in the 6th grade.

ART CHARLES: When they figured it out, it was too late. It had pretty much taken over her whole body.

LAUREN YOUNG: She lost her eyesight. And her weight dropped from 165 pounds to less than 80.

ART CHARLES: So to watch her go from being vibrant and beautiful and as strong as ever, to almost being an infant again, was tough.

LAUREN YOUNG: Deborah was only in her late 20s when she passed away from the disease. Researchers have found that some people are more at risk of this deadly version of Valley Fever; women in late stage pregnancy, immunocompromised people, and some racial minorities, including African-Americans, like Art, his son, and sister. Scientists are trying to figure out why this is happening.

KATRINA HOYER: Why do some people do just fine with this infection, they’re able to control it. They don’t even know they were infected.

LAUREN YOUNG: That’s Katrina Hoyer. She’s an immunologist and professor at the University of California, Merced.

KATRINA HOYER: What is different about the immune response in the people that get severe disease? And what is wrong with that immune response? Can we manipulate it?

[MACHINES WHIRRING]

OK.

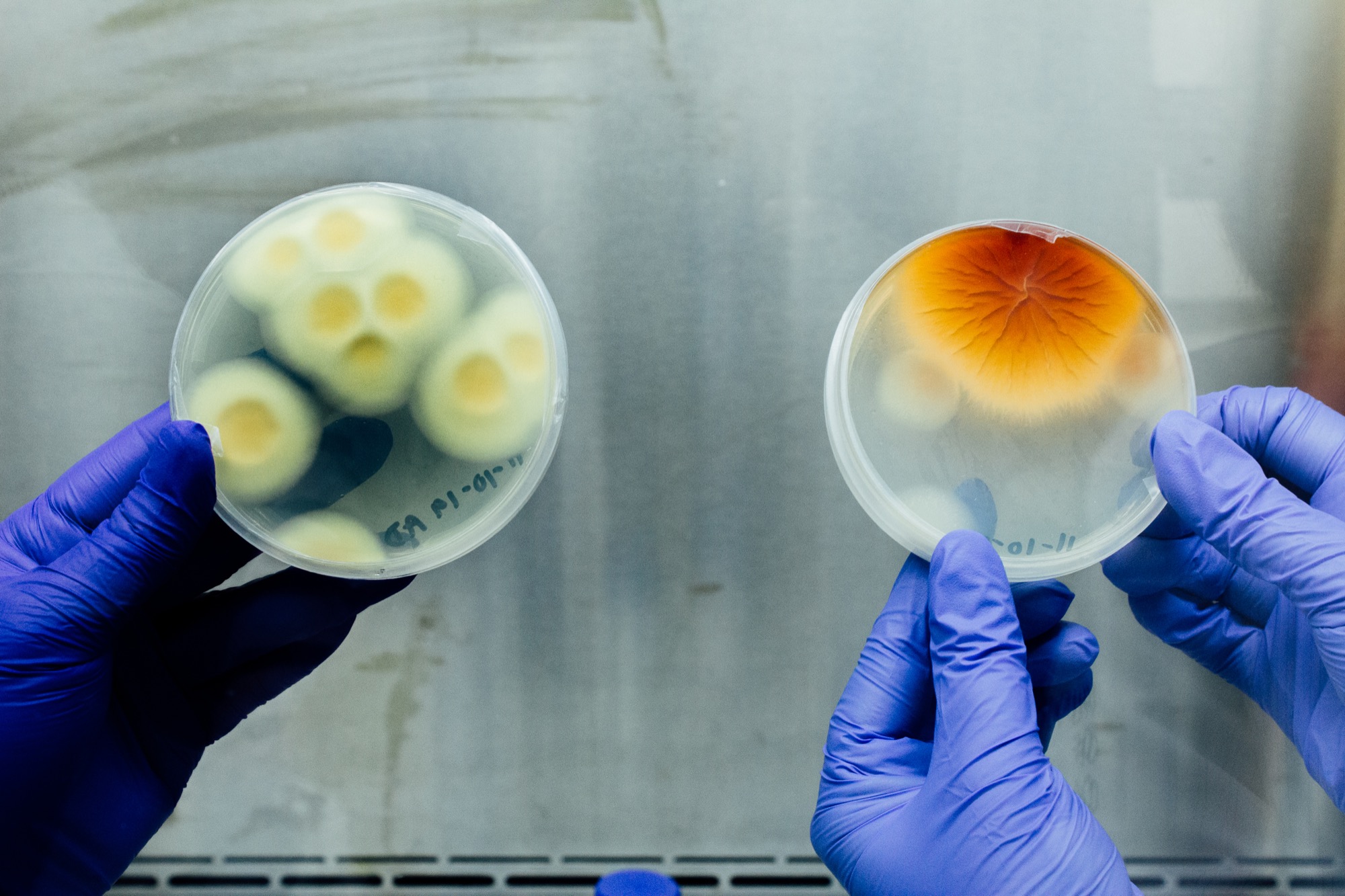

LAUREN YOUNG: In Katrina’s lab, there’s a mini-fridge-sized incubator, filled with Petri dishes of coccidioides fungus.

KATRINA HOYER: But yeah, this is the cocci.

LAUREN YOUNG: Katrina’s graduate student, Anh Diep, shows me a plate covered with white, puffy fungus.

ANH DIEP: When you grow cocci, the best sign of it is the fact that you get these like, fuzzy cottony strands, is what the field calls it.

KATRINA HOYER: So they grow in the soil in these long, string-like forms that then break apart into little spores. They get airborne. And when they enter the lung, they form these spheres that grow and then eventually rupture. So they provide this unique challenge to the immune system.

LAUREN YOUNG: It’s a war, the immune system versus the fungus. And Katrina’s watching out for misbehaving immune cells. She’s been narrowing in on one kind, the regulatory T-cells, cells that help put the brakes on the immune system.

KATRINA HOYER: And what it looks like is that patients that will go on to have chronic or more persistent infection, they have a higher frequency of these regulatory cells.

LAUREN YOUNG: More regulatory T-cells could be dampening the immune response, allowing the fungus to run amok. Other labs have looked at different types of T-cells that attack invaders. , Like in 2018 doctors at UCLA were treating a four-year-old boy with severe Valley Fever, that was causing painful skin lesions. And they noticed his T-cells were acting strangely.

Instead of gearing up to fight a fungal invader like cocci, they were targeting another kind of invader, a worm or a tick. By using a new combination of drugs and proteins, the doctors actually managed to redirect to the boy’s cells to fight the fungus. And over the course of six weeks, his condition greatly improved. His lesions vanished.

For now, this treatment has only been tried in one patient. There are more clinical trials expected in the future. But Valley Fever patients, like Art, still have to wait for a proven cure. And in the meantime, clinicians may want to be prepared. Katrina and fellow scientists say the fungus is spreading.

KATRINA HOYER: The past three years we’ve had kind of record years for infections. Part of it is with climate change, the endemic region is expected to grow.

LAUREN YOUNG: If arid-type environments spread with climate change, Valley Fever territory could too. According to researchers at UC Irvine, it could spread well into the Midwest by the end of the century. So while Valley Fever is well known in hot spots like the Central Valley, where Katrina works, it might soon be affecting many more of us.

KATRINA HOYER: Until I moved here and interacted with this community, I hadn’t talked to anybody who had ever been infected with Valley Fever or was aware of the infection. So it is definitely a regional issue. But it is a growing problem.

LAUREN YOUNG: For now, Art keeps taking his medication, an antifungal called Fluconazole. It can be brutal on the body. Dry skin, exhaustion. He might be taking it for the rest of his life. But he isn’t giving up. He’s still running around Bakersfield as a baseball recruiter and organizing activities at the local rec center. In January, he had his first grandchild. And earlier this week, he celebrated his 50th birthday. So when it comes to Valley Fever, he’s optimistic.

ART CHARLES: I’m a fighter. So it’s not going to get me. It’s going to be a battle. So if I go out, I’mma go out swinging, that’s for sure.

LAUREN YOUNG: For Science Friday, I’m Lauren Young.

IRA FLATOW: That’s a report by Science Friday digital producer, Lauren Young, for our “Methods” series. Lauren, what else can we find in your “Methods” story?

LAUREN YOUNG: Yeah, so you can listen to more of Art’s story with Valley Fever and see snapshots of his life in Bakersfield. You can also go into UC Merced’s fungal room, and see what that fuzzy fungus looks like up close. There are so many more stories from patients and scientists that you can read, watch, and listen to on our website, at sciencefriday.com/valleyfever.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you, Lauren. Terrific.

LAUREN YOUNG: Thanks for having me, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Now we’re going to dig deeper into the current treatments for Valley Fever, and talk about how different communities are being affected by the disease. Let me introduce my guests, Kerry Klein, a reporter at Valley Public Radio in Fresno, California. She covers Valley Fever, and teamed up with us on this “Methods” piece. And Dr. Anita Sil, Professor of Microbiology and Immunology at the University of California, San Francisco. Welcome to Science Friday.

KERRY KLEIN: Hi there, thank you.

ANITA SIL: Great to be here.

IRA FLATOW: Nice to have you. Dr. Sil, let’s start with you. Patients with Valley Fever can have a wide range of symptoms. Can you give us a sort of thumbnail sketch of what the fungus does to our bodies once you inhale it? How does it make you sick?

ANITA SIL: Yeah, that’s an interesting question. So spores from the fungus can enter into the lungs, just if we’re breathing in the air, especially around region where the soil can be disturbed. Then once that spore gets into the lungs, it starts to grow and senses the environment of the host.

We think the fungus has a specific developmental program that it undergoes in response to the temperature of the host environment and other cues. And that spore will enlarge. And it will generate a quite large structure called a spherule, that’s made up of individual fungal cells.

That spherule is really recalcitrant to being engulfed by some of the cells of the immune system that would normally take up foreign invaders. Instead, the fungus is able to grow in this form. And then that large spherule structure can lyse and release small fungal cells that can then move out from that original location and cause disease. So there’s a complex interplay between the fungus and the immune system that, as you say, can result in a very wide and differing range of symptoms for different individuals.

IRA FLATOW: Very interesting. Because we have a lot of people who called in to say they had a misdiagnosis of lung cancer.

ANITA SIL: Yeah, that definitely happens. Because one of the things that our bodies do when some of these foreign invaders come in, is there’s a constellation of immune cells that make a structure called a nodule that can surround, let’s say, an invading microbe. And if you can see evidence of those nodules on chest X-ray. And they look very similar to what a lesion can look like that’s cancerous. So not until you go in and biopsy that area can you see, oh, this is actually a fungal infection, as opposed to a malignancy.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. You’re listening to Science Friday, from WNYC Studios. Now, is this fungus unique to the West? I mean, do other parts of the country not have the right soil conditions? Or why do we only find it out there?

ANITA SIL: There is certainly something conducive about the climate in the Southwestern United States that facilitates growth of the fungus that causes Valley Fever, coccidioides, in the soil. But it’s not just confined to California and Arizona. There was a recent outbreak in Washington State.

You can find coccidioides in the soil causing disease in Mexico, Central America, South America. So it seems like there’s some slow spread of the organism. But the highest regions where the fungus is really found in the soil at a higher incidence, we see that in the Central Valley of California, and in Arizona as well.

IRA FLATOW: Kerry Klein, there are certain communities and demographics who have a higher risk for contracting Valley Fever. Do we know why these groups have high risks of infection?

KERRY KLEIN: I don’t think that researchers really do know why yet. It’s actually interesting. There’s a lot of parallels with COVID-19 right now. But it’s African-Americans and Filipinos seem to be more vulnerable. Those who are immunocompromised are more vulnerable. Also, folks over 60.

Researchers suspect that there are maybe some underlying immune reasons, or something that’s working or not working properly within the body. But they’re really not sure why. That’s one area of research that folks are really trying to work on.

IRA FLATOW: We’ve been seeing, with COVID-19, how the populations in prisons, they’re getting astronomical numbers of cases in prisons. Is that the same sort of thing that might be going on with Valley Fever?

KERRY KLEIN: The prisons that are in endemic areas, either in Central California or in Arizona, there have been, historically, high cases there. Because people are confined there and aren’t able to leave, aren’t able to go somewhere else. They’re not able to protect themselves. Say if they’re outside and if there’s a dust storm, or even just a little bit of dust in the air.

I think in the last couple of years case rates have actually been relatively low. But between 2005 and 2013 or so, there was a huge spike. At least, in California state prisons. And even to the point where actually, a lot of inmates themselves and their lawyers were arguing that it was a human rights issue. That the state wasn’t moving vulnerable prisoners out of those areas.

So they finally did. And that’s actually what brought the case– or one of the things that brought those case rates down really, really tremendously. So that’s an interesting story within the story of Valley Fever right there.

IRA FLATOW: After the break, we’ll be talking more about Valley Fever and the research behind treatments for the disease. We’ll be right back. Stay with us.

This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. We’re talking about Valley Fever, a fungal disease, and some of the research and treatments for the illness.

We’re talking with Kerry Klein, a reporter at Valley Public Radio in Fresno, California. She covers Valley Fever. She teamed up with this on this “Methods” story. And Dr. Anita Sil, Professor of Microbiology and Immunology at the University of California San Francisco.

Kerry, recently in California, there have been laws and budgets aimed at tackling the disease in California. What is this state focusing on, in terms of combating Valley Fever?

KERRY KLEIN: Right, so that’s absolutely true. There have been efforts and researchers and scientists working on Valley Fever for decades. But in 2018, outgoing governor Jerry Brown, in his final budget, his 2018-2019 budget, he pumped $8 million into Valley Fever research. Of course, that’s kind of a drop in the bucket for a lot of major diseases getting research funding.

But that was a lot more than had ever been put in from the state budget. And that’s a lot more than a lot of researchers are seeing. But the majority of that money went to the UC system, the University of California system. Also, the Valley Fever Institute, which is at a hospital in Bakersfield.

There, that’s upping the amount of clinical work and the amount that doctors are able to see Valley Fever patients. But then within the UC system, they’re really trying to tackle a lot of unanswered questions. So one of the projects is to investigate fundamental gaps.

So the very question that you asked, Ira, to understand why some demographics are more vulnerable than others, why the disease can be so much more severe in some people than others, one of the projects is really investigating immune disregulation. So what kinds of problems can there be in immune systems? Then, how can that manifest in how the disease occurs in certain populations as well?

IRA FLATOW: And if I understand it correctly, that’s where the research is heading at, looking at some of the more severe cases tackling the immune system. Because right now, the antifungal’s trying to kill the fungi. That’s the main thrust of treatment, is it not?

KERRY KLEIN: Yeah, that’s correct. Yeah, these antifungal drugs, yeah, are really the first and the main line of defense that doctors have. In most cases, they’re effective. Dr. Sil, correct me if I’m wrong. But in most cases they’re effective, at least in managing the disease, if not completely wiping it out.

But there are some of these really severe cases, where it’s apparent that more treatment is needed to at least bring quality of life back up for some of these patients. There just isn’t a huge arsenal of treatments out there that can really do that. So yes, clinicians really want to figure out are there different pathways? Are there different parts of the body or the immune system that we should be tackling first in order to make these antifungals more effective?

ANITA SIL: I absolutely agree. You know, there are many cases where the antifungals are sufficient. But even there, sometimes treatment can be incredibly long time period, weeks or months. And these medications have some toxicity. And then additionally, I think to complement that, our understanding of the immune system has grown by leaps and bounds in the past decade. So it will be amazing to use some of this knowledge to help augment the immune response to fungal infections, to have a much better outcome in patients down the road.

IRA FLATOW: And that’s an interesting point I wanted to talk to you about. Can the immune response tell us about how to treat the less-severe cases of this?

ANITA SIL: I think that’s certainly something on the horizon. And there’s being some very interesting work done, some of it funded through this University of California mechanism, to look at whether particular ways of modulating the immune response can help in severe disease. And certainly that will translate, I think, too. We want to have a better outcome for all individuals who are infected with Valley Fever. And I think there’s a lot of hope there.

IRA FLATOW: Your work looks at studying how the fungus knows it’s no longer in the soil, what changes the fungus undergoes once it’s in a host or a human. Right? You mentioned that something changes. What do we know about that?

ANITA SIL: Well, we know that there are major changes in the molecules that the fungus is expressing in the soil versus the host. So there are some really interesting molecular changes, as well as some very fundamental changes in what we call morphology, . Or the shape of the cells. So I like to think about in the soil, the fungus grows in this very elaborate multicellular form, where it’s got interconnected chains of cells.

It’s sort of as though the organism could forage in different directions in the soil. But that’s not necessarily the best. There are fungi who grow in that type of format inside the human body. The Valley Fever fungus is not one of them.

But instead, when coccidioides is inside a person, it changes its shape in that way that I described that must be beneficial, in a number of ways, for causing disease. As Carrie said, people have been studying this fungus for decades. There are some known fundamental changes when you compare the soil form to the host form. But really, integrating our understanding of those changes with the key elements that drive disease is something that we hope to shed some light on.

IRA FLATOW: Is the fungus dormant as it’s in the soil and waiting for a host to latch onto? And then, here come the workers and we’re going to infect them?

ANITA SIL: It’s definitely not completely dormant. I think we all hear about fungal spores. Maybe we think about you can see it when you have fruit that has gone bad, like oranges, with all this fuzzy white stuff. And you can see it. At least, in my bathroom there’s some mold spores that I need to clean up, for sure.

Fungi use spores as a way of disseminating or spreading. So it’s a natural part of the lifecycle. But in the soil, the fungus is actively growing and then just generating these spores. So that if there’s nutrient limitation in the soil, there is a dormant form that can survive until the conditions improve.

Or this is also a form that can be specialized for dispersal in the wind, or in other elements that might agitate or disrupt the soil in some way. And then there are some researchers who feel like that there could be a source of coccidioides that’s not just the soil. But because these fungi are very good at infecting all mammals, including humans, it’s possible that rodent burrows or other small mammals could also be a reservoir of the fungus, in addition to the fungal burden that’s present in the soil.

IRA FLATOW: There’s a category called orphan diseases. Is it an orphan disease and gets special treatment? Or is it not?

KERRY KLEIN: I think it is considered an orphan disease. And I think that categorization has been invoked in the past, to boost its funding. But I don’t know that that really has borne out into any sort of long-term improvements. And I don’t know that it was a tremendous amount of funding either.

IRA FLATOW: Kerry, we talked about and you mentioned California and Arizona, as both hotspots for Valley Fever. Do we expect it to be spreading more, possibly due to climate change? Is climate change a factor here?

KERRY KLEIN: Yeah that’s a really excellent question. There was just a study that came out last year, that examined that very question. The fungus coccidioides is found in 12 states right now. And that under a high-climate-warming scenario, by the year 2100, that could jump from 12 to 17 states by the year 2100. Which would double the amount of geographic area where the fungus could grow. And that could raise the case rate by as much as 50% over what it is now.

Of course, we may not follow that exact scenario of high climate warming. But the reason for that would be because so much more of the US could become a little more arid, a little bit less humid, and a little bit hotter. And those might just be the right conditions to grow coccidioides.

IRA FLATOW: We’ve run out of time. I’d like to thank my guests, Kerry Klein, a reporter at Valley Public Radio in Fresno. She covers Valley Fever, and teamed up with us on this “Methods” piece. And Dr. Anita Sil, Professor of Microbiology and Immunology at the University of California, San Francisco. And you can read, listen, and learn more about Valley Fever by our digital producer, Lauren Young. You can see all of her reporting as part of our “Methods” project. It’s up on our website, at sciencefriday.com/valleyfever.

Copyright © 2020 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.