Uncovering Metal Crafts Of The Viking Age

11:50 minutes

Vikings are often associated with scenes of boats and fiercely-pitched battles. But new research, published in the journal Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, shows they also had other, calmer skills. The paper details advances in the cast metalwork of objects, such as keys and ornamental brooches, that occurred in the trading city of Ribe, Denmark in the 8th and 9th century.

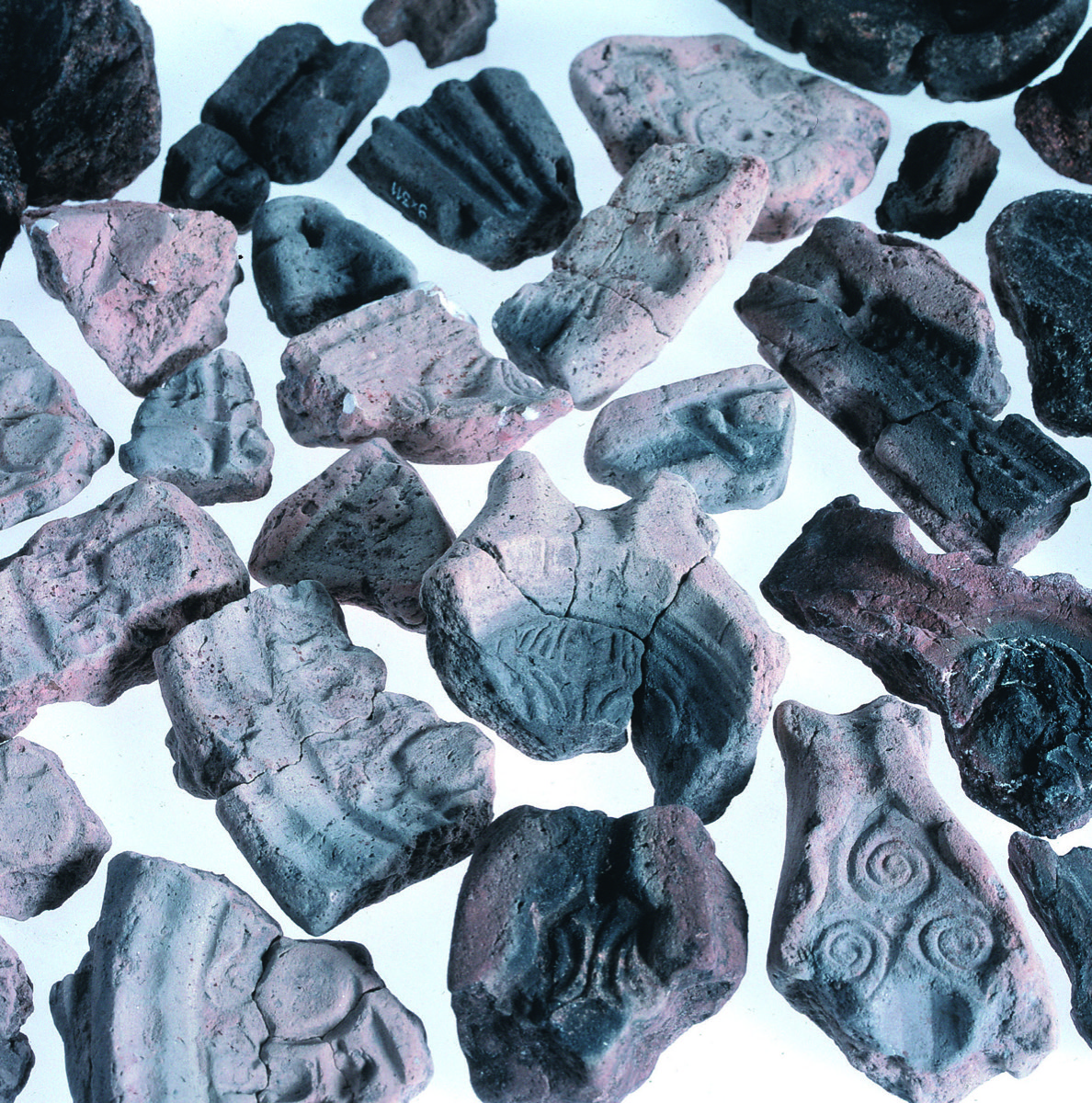

Researchers analyzed samples of metal taken from a variety of metal objects found in Ribe, along with metalworking tools, crucibles, molds, and samples of metal slag. They found that while the Vikings began working in brass with a very experimental approach, they quickly standardized their production to use specific blends and alloys of metals. They also adopted more heat-resistant clays for crucibles, and made extensive use of recycling throughout their work processes.

Vana Orfanou, an European Research Commission (ERC) postdoctoral research scientist In the School of Archaeology at University College, Dublin, and lead author on the paper, joins SciFri’s Charles Bergquist to discuss the state of the art in early Scandinavian brass making. See more photos of Viking metalwork artifacts below.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Vana Orfanou is an ERC postdoctoral research scientist in the School of Archaeology at University College, Dublin in Dublin, Ireland.

JOHN DANKOSKY: This is Science Friday. I’m John Dankosky. Ira Flatow is on vacation. Later this hour– that imported coffee you’re drinking wasn’t just grown in Brazil. It was pollinated there. A conversation about global food systems and protecting pollinators around the world. Plus, we imagine some possible and not so possible futures.

But first, new archeological research on the Vikings. SciFri’s Charles Bergquist is here to tell us more. Hi, Charles.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Hey, John. When I say Viking, what do you think of? And don’t say hats with horns.

JOHN DANKOSKY: OK, no hats with horns. Maybe warships, battles, pillaging?

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Right, right. Those are all common reactions, which is why I was interested to read this article in the journal Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences about the Vikings as really skilled metalworkers.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Oh, yeah, metalworkers. You mean making swords and armor and horned helmets all for that pillaging that they do?

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Yeah, no, they’re talking about developing the blends and alloys used in finer, molded cast metalwork like brass brooches and keys, and how over the course of just a few generations they’ve really advanced their metallurgical skills.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Oh, really? Interesting. So how did they find this out?

CHARLES BERGQUIST: So these researchers analyzed samples of metalworking tools and ingots and metal products, all from the coastal town of Ribe. Today, it calls itself the oldest town in Denmark. It dates back to around the 8th century, and it eventually became an important site for the Vikings, an urban location of maybe a few thousand people with workshop areas, and it was a trading center. It’s what archaeologists call an emporium.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Oh, so like a big arts and crafts fair where you could see some of the state of the art in Viking material science.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Yeah, and sell them to places in your neighborhood. Dr. Vana Orfanou is an ERC postdoctoral research scientist in the School of Archaeology at University College Dublin, and she’s lead author on this paper. I asked her to give me a picture of what metalwork was like in the rest of the world at the time.

VANA ORFANOU: Brass was known in the Iron Age. We have brass examples from the Late Bronze Age, but all these are accidental alloys. They were made accidentally because of the minerals that they were chosen.

The first who mastered, let’s say, the technology of brass and were able to manufacture it in almost an industrial scale were the Romans. So we see a peak in brass production in the Roman times. But then, brass kind of like fades out of the picture of European metallurgy in the post-Roman period.

And then again, in the mid-7th century, in the mid-Saxon period, we have a re-emergence of zinc in copper alloys. And that’s when Ribe is established as well. So the material in Ribe coincides with this new wave– some people have even called it the third phase of brass, which in a way it continues up until today, because we use brass in everything in our homes today. So this is, when it comes to copper-based alloys, a picture of that period.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: In this study, you’re looking specifically at non-iron metals. Why is that? Why is there this distinction between the iron-based materials and the not-iron-based materials?

VANA ORFANOU: Excellent question. First of all, because in the whole of Scandinavia, we don’t really have copper ores. So when we find copper, we know that it was imported, whereas iron, it was more easily to be locally found and smelted and hammered into whatever, a knife or a sword. But there is a very interesting technological distinction, and we cannot assume that people who worked with copper also worked with iron, because essentially they’re different technologies.

For the single region, the first time that people managed to melt, to liquefy, iron, that was in the 15th century, not before. So before the 15th century, all iron production is kind of like solid-state metalworking, whereas copper– yes, you melt copper, you can mix it with other alloys, you can be more creative. And that’s also what we see in Ribe, where we see copper-based alloys. We see copper and tin, copper and zinc and lead in various ratios and combinations. But we also have, along with this, we have the technology of silver and gold, because, again, you can melt silver and gold.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: So beyond the brass that you were looking at, they were using precious metals in these workshops, too?

VANA ORFANOU: Yes, absolutely. We do see this mostly in the analysis of the byproducts of the metallurgy, the ceramic crucibles and the molds. This is where we find traces of silver and gold. We don’t have objects of silver and gold or silver and gold alloys, because as you can imagine, these would have been very highly prized, and they would not have let the gold and silver end up in the waste heap in the ground. They would have reused it in the future. So we don’t have objects, but all the other traces, yes, they do point that alongside the copper-based production, there was precious metal production as well.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Where were they getting the actual metal? Was it from very far afield?

VANA ORFANOU: A study from a very good colleague, Stephen Merkel, who analyzed the provenance of brass ingot bars from Hedeby, northern Germany, has some very interesting results. They’re not conclusive, but they’re still very interesting. So Stephen Merkel says that these bars, it is very likely that they came either from the Balkans or from Andalusia, from the Iberian Peninsula. In either case, this means that they were part of a long-distance exchange network. And they ended up in Germany, and maybe in Denmark as well.

There’s another step in the process that is involved, which is copper alloying, because– and that’s a problem with provenance studies. Even if I tell you, yes, this copper was coming from this little village in Serbia or from this little village in the coast of Iberia, that’s the copper. But what I found, I have brass bars. And at some point, the copper was alloyed with zinc.

So this could have taken place in a completely other place. This could have taken place in Germany somewhere, because the Rhine, which flows and ends up close to Amsterdam, was contributing to the seaborn trade. And this is how these metals ended up in Denmark and northern Germany, most likely through the Rhine. So anywhere along the Rhine, this could have taken place.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: So they may not have been blending and alloying the metals themselves. They may have been buying pre-made alloy blends from elsewhere.

VANA ORFANOU: Oh, most likely. Most likely. And that’s why we find them in ingot form. An ingot is a shape of a metal that is tradeable. It’s like a trademark. The form tells you something about the quality of what you’re buying.

So you’ll have these nice bars, and you can see the color. The color’s already an indication of how much zinc is in there. So what we do see in these Viking emporia, in these Viking trading ports, is that they do have a flair for 20% zinc brass, which is a brass that looks very much like gold. I think this is another very interesting aspect of brass, because it gives people another way to express themselves. It’s another way of expressing your identity with something that looks gold. It’s not gold, but many people would not know this.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Were they blending metals according to a recipe? I’ll take three ingots of this and a half ingot of that? Or was it just a knowledge that, oh, if I buy ingots of this specific color from that source, they’re going to do what I want?

VANA ORFANOU: Yeah, it’s a bit of both, because you choose your brass ingots– the yellow, the shiny– but at the same time, in Ribe, we do have small lead bars, which basically they come from Germany. We have done some analysis in another paper, and these come from Germany.

So the craftsperson or the artist in Ribe would have the brass coming along the Rhine, maybe from the Balkans, maybe from Andalusia, maybe from somewhere else. He would also have the lead coming from Germany. Lead is much cheaper. And I think you would want to add lead wherever you would get away with it, because a key does not have to look nice, so if you can make it in a cheaper way, then why not? People have been very efficient.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Interesting. So you talk a bit about how rapidly they seemed to advance in their technique. Give me a sense of that. How quickly did their metalwork improve over the course of this century?

VANA ORFANOU: Right. So we purposefully divide their material to the 8th century and the beginning of the 9th century. So we’re looking mostly at the last few decades of the 8th century and the first few decades of the 9th century, so we’re talking about this period. In the 8th century, this is where we see a more– I’ll call it random, but not with a negative connotation, not with a negative sense. More experimenting, I have the feeling. They’re more happy to use whatever it works.

From the 9th century, it seems that they have already decided what they want. They want brooches with 20% zinc. They’re not mixing anything else. And they are making brooches with 20% zinc in the copper. So it’s so standardized, what we see in the material, that cannot be an accident.

Now, how many years would a metalworker work depends also on the life expectancy, but let’s say they work 20 years. So we would have two generations in the 8th century, and then they have already maybe the grandchildren. I’m very simplifying here, but maybe the grandchildren of the first metalworkers at Ribe, they already had set their standards.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: What would be the equivalent job of these metalworkers today? Should I be thinking of them like jewelers, artists, or something more mundane?

VANA ORFANOU: That’s the million-dollar question, because when we look at all crafts in the past, sometimes if something looks nice, we call them artists. If something is a fitting or a key, something that we use every day, then we call them craftspeople. I would call them specialized skill force. Irreplaceable, I would say.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Does this specific knowledge about how they worked their metal tell you anything larger about Viking culture as a whole?

VANA ORFANOU: It does. Every technology of every period is a mirror of how the society is organized. So if we find some level of standardization in the metallurgy from a point on, I can with relative safety say that this standardization would be mirrored in all other technologies. And that’s why, as an archaeologist, I’m also very keen to study past technologies, because they do tell us a lot about how people think.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Dr. Vana Orfanou is an ERC postdoctoral research scientist in the School of Archaeology at University College in Dublin. Thank you so much for joining me today.

VANA ORFANOU: Thank you very much, Charles. Bye.

Copyright © 2021 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.