How ‘Science Interpreters’ Make Hidden Science Visible

17:43 minutes

Imagine you’re diving into a cell. You’re paddling around in the cytoplasm, you’re climbing up a mitochondria. If you’re having a hard time picturing this, that’s okay! There are professionals who do this for a living.

We wanted to learn more from expert science interpreters, who take the results section of a research paper and translate it into something tangible, like a 40-foot dinosaur skeleton or a 3D animation of cellular machinery too small to see.

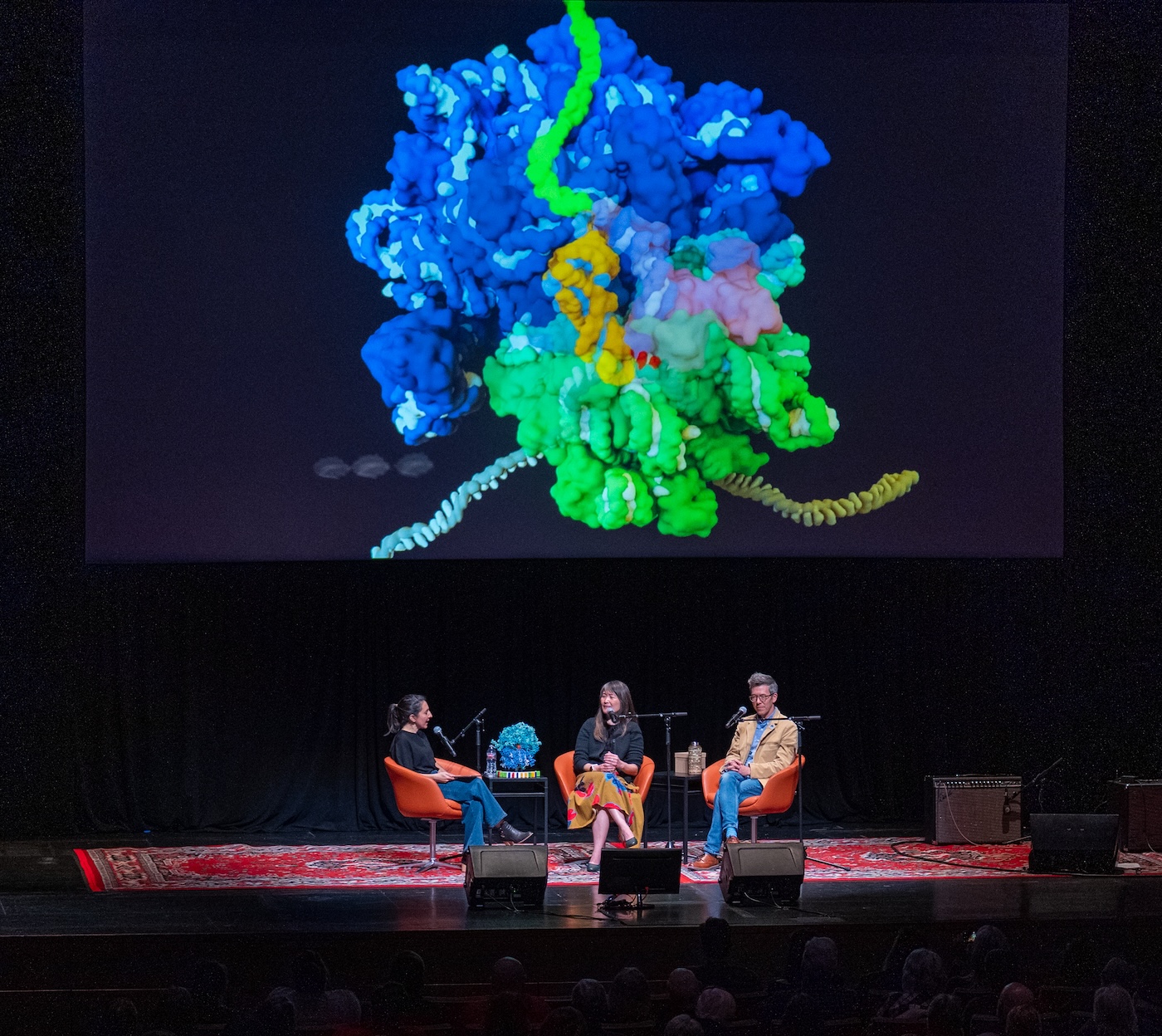

At a live event in Salt Lake City in March, Host Flora Lichtman spoke with Dr. Janet Iwasa, head of the University of Utah’s Animation Lab and director of the Genetic Science Learning Center; and Tim Lee, director of exhibits at the Natural History Museum of Utah, about how they bring these out-of-reach worlds to life.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Dr. Janet Iwasa is head of the University of Utah’s Animation Lab and director of the Genetic Science Learning Center in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Tim Lee is director of exhibits a the Natural History Museum of Utah in Salt Lake City, Utah.

FLORA LITCHMAN: This is Science Friday. I’m Flora Lichtman, live with KUER from the Eccles Theater in Salt Lake City, Utah.

[CHEERING, APPLAUSE]

OK, I want to do an experiment. Close your eyes and imagine diving into a cell. You’re paddling around in the cytoplasm. You’re climbing up on a mitochondria. If you’re having a hard time picturing this, that’s OK.

There are professionals who do this for a living. Our next guests are expert science interpreters. They take the results section of a research paper and translate it into something tangible, like a 40-foot tall dinosaur skeleton, or a 3D animation of cellular machinery that would be too small to see.

Here to tell us how they bring science to life are Dr Janet Iwasa, head of the University of Utah’s Animation Lab and director of the Genetic Science Learning Center, and Tim Lee, Director of Exhibits at the Natural History Museum of Utah. Welcome to you both to Science Friday.

JANET IWASA: Thank you so much.

TIM LEE: Thank you so much.

[APPLAUSE]

FLORA LITCHMAN: OK, Tim, I feel like you have a lot of people’s dream job. When you were a kid, and other kids were like, I want to be a fireman or a marine biologist, were you like, no, I want to make dioramas?

[LAUGHTER]

TIM LEE: It was actually quite accidental but inevitable. If you would have asked me as a six-year-old, I would have said I was going to follow in my immigrant dad’s footsteps and become a doctor, a brain surgeon. But the signs were there.

I loved going to museums with my family. I loved dioramas. I had a sketchbook of all the things that I observed, and it helped me make sense of it– the wondrous world around me, all the different landscapes, and things that I saw.

And I also collected things. I had a massive collection of objects. And depending on how precious I thought they were, sometimes I’d even ask my friends to wash their hands before they touch them.

[LAUGHTER]

FLORA LITCHMAN: You had your own personal collection, and it was white glove service only.

TIM LEE: That’s right, yeah.

– I go to AMNH often, the American Museum of Natural History near where I live, a lot with my kids, and I still love the dioramas so much. Why do you think the dioramas have such a hold on us?

TIM LEE: I was always that kid that was looking for the assignment to add a diorama. So if it was a book report, if it was a science report, there had to be a diorama. But I think it’s really our curiosity about our land and where so many of our stories come from. It helps us imagine and immerse ourselves in a moment of time that really starts to capture the imagination. And dioramas are a classic. They’ve been there forever. It’s one of the most pure forms of natural history display.

FLORA LITCHMAN: Janet, you’re a scientist, and I heard you got into your line of work, animating science at a lab meeting.

JANET IWASA: Yeah, that’s right. So I was studying cell biology in graduate school when I was studying for my PhD. And in cell biology and molecular biology in general, the way that we communicate ideas most often is by drawing circles and squares and arrows. And we’re like, these are molecules, and this is what they do.

FLORA LITCHMAN: Like a stick figure.

JANET IWASA: Like a stick figure, like a very simplistic stick figure. But what we’re actually studying is super complex. They’re very, very dynamic, and they have real shape. And they’re doing something super interesting in a very crowded environment.

And the first time I saw an animation of a molecular process was during a group meeting, which was when the labs get together, and one person from the lab shares their data. And so one of the lab meetings I went to when I was in grad school, they shared this animation of how they thought one of these proteins worked. And it made me realize that the stick figures don’t work for me. I think I really need something a little bit with– that animation really helped me understand how things worked.

FLORA LITCHMAN: So how does your lab work? Do researchers come to you from your institution, from other places and say, I’ve got this research– can you help me animate it? Or what’s the process?

JANET IWASA: Yeah, so that is a part of the process. So I have postdocs in my lab who are interested in– we basically do collaborations with researchers around the world. And they often have a specific kind of molecular process they’ve been studying for years, sometimes decades.

Yeah, and they come to us saying, we have this idea. We have a movie in our heads of how we think this thing works, but we have no way of creating this, being able to show people what we think. So yeah, so we help them with that process.

FLORA LITCHMAN: So you have to get that movie out of their head.

JANET IWASA: Yeah, so it’s a lot of really just understanding what is that movie? And then trying to figure out, OK, now that we understand what they think is happening, how do we use these traditional animation tools to do something that it was never really meant to do? Because we use software that’s from Hollywood that’s really made for animating, like superheroes, Pixar kind of movies. And then we use that software, and we’re like, OK, how do we make that– animate a virus, for example?

FLORA LITCHMAN: That’s so cool, Tim, one of the things you’ve been working on is updating the diorama, like diorama 2.0. Tell me about projection mapping.

TIM LEE: Yeah, that’s right. So can I tell you a little story?

FLORA LITCHMAN: Yes.

TIM LEE: So imagine a day like any other day at the Natural History Museum of Utah. I was at my desk on the fifth floor, and I was probably designing a really cool exhibit when all of a sudden, I got a radio call from one of our educators that said, Tim, we have an issue in our diorama section. You have to come check it out. 7

FLORA LITCHMAN: That’s always the call you want to get, I’m sure.

TIM LEE: Yeah, exactly. So I hustled down to the fourth floor– this is our life gallery– and I see a classroom of probably seven eight-year-olds that are actually in our dioramas. Our dioramas don’t have glass in front of them. They’re accessible.

And the kids were so engaged and so amazed by the different ecosystems that they represented that they were in there exploring the cacti, the hummingbirds, the elk. And that actually– I could have been horrified, but I was inspired because I saw the opportunity that dioramas could be a lot more.

So I started to think about what we could bring to that traditional form. We could embed live animals. We could embed sound and scent and projection mapping. And what projection mapping is, is filming animals, in this case, and then projecting them onto the dioramas. So it really activates the diorama.

And instead of a frozen moment in time, you can really tell a story. And at its essence, that is what exhibits do. They help scientists and researchers tell stories.

FLORA LITCHMAN: What was it like to film the animals?

TIM LEE: Oh, boy, that was a challenge. So I’ve seen a few BBC documentaries, and I thought this should be pretty easy. So one of the first things we do when we make exhibits is we make a team. So I knew I had to surround myself with filmmakers who had some green screen experience. But really, animals are animals. So we created a script for foxes, raccoons, birds. But actually, Flora, can you guess what animal we had most trouble with?

FLORA LITCHMAN: Does anyone have a guess.

AUDIENCE: Cats.

TIM LEE: Cats, yes. You win!

[APPLAUSE]

FLORA LITCHMAN: Anyone who has a cat actually would probably guess a cat.

TIM LEE: The cat was completely uncooperative.

[LAUGHTER]

FLORA LITCHMAN: Janet, do you have any animation pet peeves?

JANET IWASA: Hmm. I guess, there are some times– so color is an arbitrary choice in molecular animation because molecules, most of them are smaller than the wavelength of light, and so they actually don’t have color. And we often like to choose nice colors for our animations. But there have been times when people are like, no, we want the most garish colors possible.

[LAUGHTER]

FLORA LITCHMAN: The researchers are like neon orange.

JANET IWASA: Yes, exactly. Everything neon. And we’re like, OK. But yeah, so there are sometimes silly–

FLORA LITCHMAN: What about the popular versions of science animations?

JANET IWASA: Yeah, that can be probably– so when you say popular, do you mean things that appear on Science fiction–

FLORA LITCHMAN: Shows, TV.

JANET IWASA: –and movies?

FLORA LITCHMAN: Yeah.

JANET IWASA: Yeah. So my kids, who are here, would probably complain that they cannot watch. If there is any kind of part of a science film or a science fiction film that has something where they zoom into DNA, and it’s mutating, I will always be complaining about that structure because the structures are available. They could use real structures, but they never do. So yeah, so things like that. I think I am probably the worst person to watch those kind of movies with, because I’m always just muttering to myself and kind of–

[LAUGHTER]

FLORA LITCHMAN: I mean, you’re visualizing things that are too small to image, right? Do you have to take– do you take creative liberties? Are there places where you get to, I don’t know, where you use your imagination?

JANET IWASA: I would say that– so most of our projects are really in close collaboration with researchers who have been studying something for years or decades. And the way that people come up with these hypotheses, these kind of the movies that play in their heads are from their own data, but also from data from the community and a lot of indirect information. And so they’re piecing together this story based on that.

And so the way I think about our animations is it’s often a reflection, an individual reflection of somebody’s hypothesis that they’ve developed in their own head over the course of these years and decades. And everyone, even in the same field, might have a slightly different version of that movie. Yeah.

FLORA LITCHMAN: Do they understand it better after they see your work?

JANET IWASA: I think sometimes people realize that it’s an intuition builder. So they’ll watch the animation, and they’ll be like, but that’s not how I thought it would happen. But that’s exactly how they described it. And they’re like, we need to go back and do some experiments to figure out whether they’re– because there’s something missing here. So sometimes it does build that intuition. And sometimes just building the animation reveals issues that things don’t quite fit together the way they expect.

FLORA LITCHMAN: Tim, how do you think about the role of museums in the future?

TIM LEE: I think involving our communities is a big part of the future of museums, not only so that young kids can see themselves as scientists, but also so they can participate in science. So there are community science projects out there that our visitors can play a role in and contribute to. I think that’s a big part of the future of museums.

And then I also think that showing that scientists don’t look one way, that they can look a lot of different ways so that anyone can identify with that story and see that science isn’t apart from your day-to-day life. It is part of your life.

FLORA LITCHMAN: We’ve got a question from the audience. Go right ahead.

CAROLINE: Hi, there. My name is Caroline, and I’m a recent University of Utah graduate in genetics and genomics.

[APPLAUSE]

So I am very familiar with some of both of your work. And a lot of the researchers I worked with showed us the animations, but I’m recognizing and noticing that I feel like I didn’t see lots of that when I was growing up in studying science. And I feel like that would have been really nice to see. My question for you is, are there current initiatives to get these animations more into younger institutions and schools?

JANET IWASA: Yeah. So yeah, so I’ve definitely collaborated with textbook publishers to create animations that are incorporated in there. And I think with the move towards digital publishing, it’s becoming a lot more popular to consider how do we make these things more engaging?

The other kind of plug I’m going to put out there is that I’m now director of the Genetic Science Learning Center at the University of Utah. And if you go to our website–

[APPLAUSE]

–so learn.genetics.utah.edu is free. We do a lot of middle school and high school level science education. It’s used in classrooms around the country. And there are a ton of really great animations and games on there that teach all levels of science, all different, not just genetics. We also have geology. But yeah, and so I’m hoping to also incorporate some of those molecular animations into our resources on learn.genetics.

FLORA LITCHMAN: We’ve got a lot of questions from the crowd. Let’s go to one more.

WAN: Hi, my name is Wan Han. I wanted to go ahead and then ask, since so many of these components, like organelles and other features of a cell, are so minuscule, for the things that we are able to visualize through, for example, scanning or transmission electron microscopy, how do you reconcile these images that we’re able to see with the naked eye with what the researchers have envisioned? And what’s maybe a recent example of that that you’ve worked on?

JANET IWASA: Yeah. So a lot of our animations, we combine things at different scales. So like you mentioned, some things we have that are visible with light, and some things are much smaller. So what we generally do is we combine all of those different types of data sources. So molecular-level things usually require one type of experimental data. Looking at organelles is usually a different kind, and cells a different kind.

So we usually kind of just combine all of those things to create a multi-scale visualization of basically what’s happening inside cells to give life to those molecules, to provide them that context of the organelles. But yeah, it’s a great question. I think a lot of the work that we do is about the synthesis of all of this data.

FLORA LITCHMAN: We know that trust in science has declined in recent years and in expertise and institutions. Do you feel like your work has a role to play in this? And I want to hear from you both. I’ll start with you, Tim.

TIM LEE: Yeah, 100%. Museums are something that kids start to experience at such an early age, yet they provide an opportunity to bring science to everyone’s lives at any age. That intergenerational learning and experiencing is so, so big.

We have collections that we use to draw upon to tell stories of research and science, current and in the past. We involve our communities as well to participate in science to show that they can be contributors. Even if you don’t feel like you are part of it, that there is a voice for you in science. And the ongoing pursuit of knowledge to better understand our place within the natural world and to plan for our future is something that museums can be the interface for.

So I see museums as community centers. I see them as places where people can raise questions and use science and collections to help answer them. And I see them as places which will really take science and show that this is something that we have to provide for every generation.

JANET IWASA: Yeah, and I actually went to a program at the Natural History Museum that taught scientists how to communicate their research to the public. And that’s a great experience. And I think that’s kind of indicative of I think, what maybe more scientists should be thinking about doing.

The animations are about communicating our research to a broader audience. And we can probably maybe do a better job getting out there and trying to make sure that we’re really trying to communicate our research as well as we can through museums, collaborations with museums, using social media, using animations and visualizations to make the things that are of hard to access a little bit more accessible.

FLORA LITCHMAN: Well, thank you for making your work so accessible tonight. I really appreciate it. Thanks for joining us.

JANET IWASA: Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

Dr. Janet Iwasa, professor of biosciences who runs the University of Utah’s Animation Lab, and Tim Lee, Director of Exhibits at the Natural History Museum of Utah.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

That’s the show. Special thanks to the team of people who made tonight’s event happen, including our musical guess for the evening, Staycation.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Our fabulous partners at KUER, everyone here with us at the Eccles Theater, all of our guests on stage tonight, and the entire Science Friday team.

IRA FLATOW: From Salt Lake City, I’m Ira Flatow.

FLORA LITCHMAN: I’m Flora Lichtman.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you, Salt Lake City. Have a good night.

[CHEERING, APPLAUSE]

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Copyright © 2025 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Dee Peterschmidt is a producer, host of the podcast Universe of Art, and composes music for Science Friday’s podcasts. Their D&D character is a clumsy bard named Chip Chap Chopman.

Flora Lichtman is a host of Science Friday. In a previous life, she lived on a research ship where apertivi were served on the top deck, hoisted there via pulley by the ship’s chef.