Get Your Future Issue Of ‘Your Martian Daily’

Tips from a NASA astronaut for what to eat, how to dress, and how to manage your modern life on Mars.

You’ve just completed a long flight to Mars, and you want to get out under the pink, hazy sky. It’s about time to kick back on the Red Planet for a catnap outside in the sun, right? Wrong.

While the sun’s rays would be much weaker on Mars than on Earth, the radiation dosage and the Red Planet’s thin atmosphere would make for a rather hazardous sunbathing experience for us Earthlings. That’s certainly not the only thing you would have to get used to in your new life on Mars.

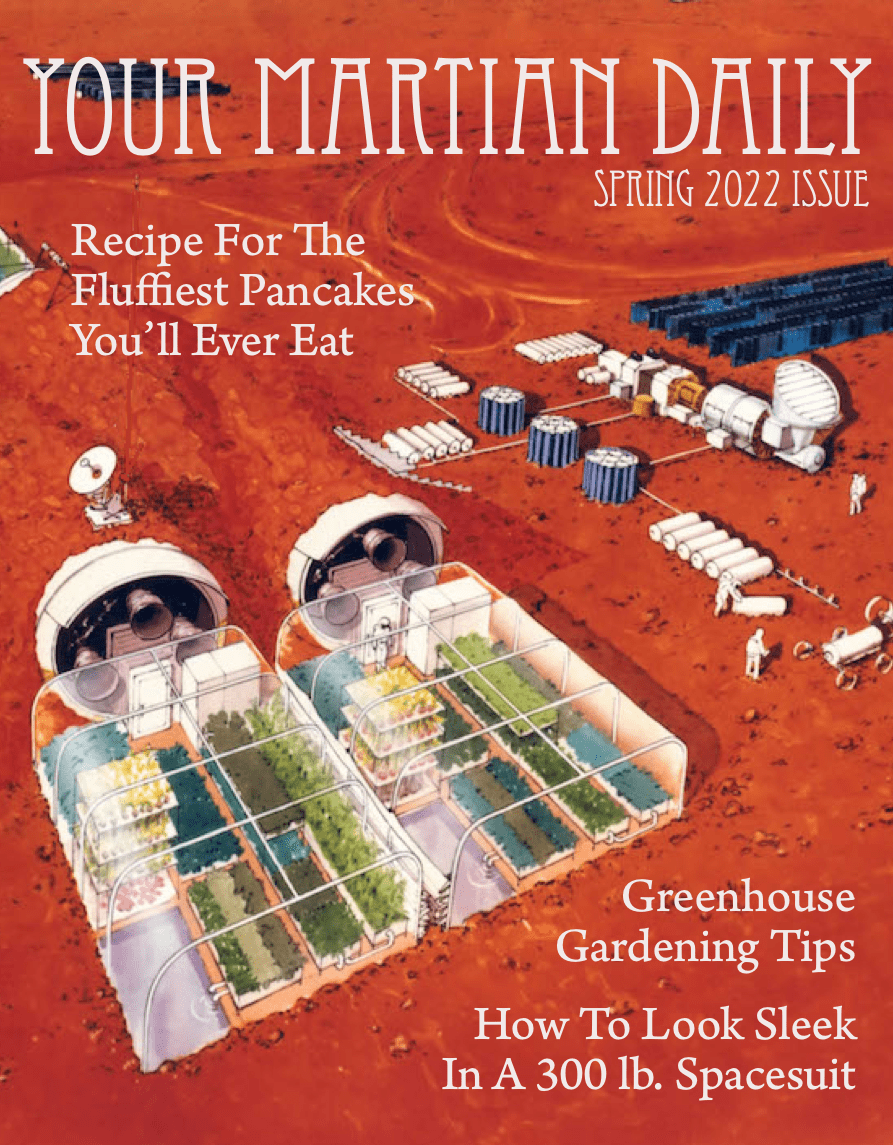

“On Mars, you can’t go outside without putting on a 300-pound spacesuit,” Stan Love, an astronaut and planetary scientist at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, told Science Friday in a recent panel interview alongside a space futurist and aerospace engineer. “The scenery is rarely going to change. The people are rarely going to change. You have to live in a sealed habitat.”

We may encounter such conundrums in the not-so-distant future. SpaceX’s Elon Musk estimates that a rocket capable of interplanetary travel might be ready for testing as early as next year, with plans to deploy a cargo mission to the Red Planet by 2022 in preparation for building a human colony. While Musk dreams of grabbing a slice at a Martian pizza joint and sidling up to a cocktail at “Mars Bars,” that got us thinking: If we get there, what would daily life really be like on Mars? And you had plenty of questions, too.

So, we asked an astronaut. SciFri pulled some of the questions you had during the radio show and sent more to Love to find out more about what daily life might be like in the future on the Red Planet.

How would a frisbee behave if thrown on Mars?

— David M. Norton (@True2TheTigers) March 16, 2018

Stan Love: If you threw a frisbee on Mars, its behavior would depend on whether you were indoors or outdoors. Outdoors, the very thin air would create no lift, so the frisbee would fall to the ground like a rock, although it would go farther than you might expect for a rock because of the lower gravity. Indoors, with Earth-normal air, the frisbee would generate lift as it does on Earth, but the lower gravity on Mars would let it fly much farther than it would on Earth. It would also be able to fly much slower than it could on Earth, since it would need less forward speed to generate enough lift to balance the lower gravity.

*Ferhat Bingöl (@FerhatBingol): Can you explain the day and night and sleeping hours, seasons, years?

Stan Love: On Earth, a day and a night last 24 hours. On Mars, it’s 24 hours and 40 minutes, so day and night happen on something like a normal schedule. Mars’ rotation axis is tilted like Earth’s, so there are warmer and colder seasons with longer and shorter days, just like on Earth, but a full season cycle takes a whole Mars year (about two Earth years), and even in “summer” it’s brutally cold.

The daytime sky on Mars is pinkish because of the tiny dust particles suspended in the air. Sunrises and sunsets look blue because near the horizon the sun’s rays must pass through a lot of that pink dust before they get to you, and the dust scatters the red light away.

There is water on mars. But it is safe to drink? Or is it contaminated with some heavy metals? to clean is possible but need some serious machines. (e.g. reverse osmosis etc) or is there an other way to ensure a water supply?

— ? *flap* ? (@_Quaestor_) March 15, 2018

Stan Love: I’d want to filter and purify that first. We know you mentioned the perchlorates in the soil. Water on Mars is all frozen or in the vapor form. Liquid water can only exist in certain low lying areas on certain very warm days. So we’re going to probably mine it out of the soil in the form of ice. You would have to melt it, make sure you get all the grit out of it. With the chemistry going on in the Martian soil, you’d want to make sure you ran that through some filtration before you chugged it down.

What kind of agricultural / agronomic systems are being considered for Mars? How are these different than considerations for closed space ship / station systems? How do these involve in long term development of biomes / ecosystems?

— (((William Coney))) (@WilliamConey) March 15, 2018

Stan Love: We have no possibility of producing food on Mars right now. The closest analog we have to that would be the very small, brightly lit greenhouse room they have at the South Pole station in Antarctica for the long winter. There’s no flights in and out, and all the food that the folks eat has to be either frozen, thermally stabilized, or occasionally, you get a little bit of lettuce or a tomato out of that greenhouse, and it’s the highlight of your day.

…If you look at what we get with an acre of farmland on Earth without thinking about it, every square yard of that field receives about a kilowatt of light energy from the sun all day. That’s a lot of grow lights, and it takes many acres to feed a colony. So we’d need the volume to put all those plants in. We’d need all the light to make the plants grow, and then of course, every watt of artificial light, once it’s been projected out, becomes a watt of artificial heat that you have to get rid of. And in space, getting rid of waste heat is really hard… [Imagine], go in your bathroom, turn on eight hairdryers, and leave them there for an hour or so. And then go back in your bathroom. That’s what it’s going to be like being in a room with grow lights on Mars.

My 7 year old daughter wants to know what Mars could smell like and if there could be places that could smell different like on Earth, because it seems like it all looks the same on Mars. #SciFriLive

— ?Tamara? (@Aviatrixt) March 16, 2018

Stan Love: Nobody will ever know what Mars smells like because the air is too thin to breathe. If you tried to breathe it, you would fall unconscious before you could smell anything, and die pretty soon after that. If you compressed Mars air until it was thick enough to breathe, it would sting your nose and throat horribly because it’s mostly carbon dioxide. If you’ve ever felt your nose sting when you burp after drinking a lot of soda, that’s what a little bit of carbon dioxide does. On Mars, it’s all carbon dioxide.

If there were Martian creatures that could breathe Mars’ atmosphere normally, they probably would notice that different places on Mars smell different. Mars’ soil has different minerals and different amounts of water depending on where you are, and those things affect how a place smells.

How might the different UV exposure and lower gravity affect the transmission of common human pathogens (e.g. would rhinoviruses not survive well/would sputum particulates travel farther?)

— Adam Netzer Zimmer (@acnzimmer) March 15, 2018

Stan Love: On Mars, a disease-causing germ let loose outdoors would perish immediately because of the cold, dryness, ultraviolet light, and powerful oxidants in the dust. But the person who sneezed it out—and any person who might breathe it in—would be dead, too (see answer above). Indoors, with normal atmosphere and humidity, and protection from the UV (normal window glass blocks UV very well), your sneezes would indeed float around longer because there’s less gravity to pull the particles down to the floor.

How would we handle outbreaks of disease on Mars? It would be hard to send help, right? @scifri

— Mel Marie (@MoLikesPoe) March 16, 2018

Stan Love: If there was a disease outbreak on Mars—and we hadn’t invented some kind of warp drive—it would take at least nine months and as long as three years, depending on how the planets line up, to send aid from Earth. For a disease outbreak (or any other problem requiring a shipment from Earth sooner than 9 to 35 months), the colonists would be on their own.

Would the human resting metabolic rate go up or down? I have a few pounds to lose and wondering if I should look into martian real estate.

— Sarah Thompson (@NdaNile) March 15, 2018

Stan Love: I’m not a biologist, but I would expect that your resting metabolic rate wouldn’t change much on Mars. Being a couch potato takes very little energy no matter what planet you’re on. On the plus side, moving to Mars sheds pounds like crazy: Five-eightths of your body weight disappears from the scale as soon as you get there! But that’s just because the gravity is less. Your mass wouldn’t change, and you wouldn’t look any thinner, which is what most people have in mind when they’re thinking about weight loss. For a healthy body composition, Dr. Love recommends a sensible diet and plenty of vigorous Earth-gravity exercise rather than Martian real estate schemes.

Oh, @scifri did you HAVE to mention PANCAKES at the carb-craving hour of the afternoon?

Please tell me they would not be as fluffy on Mars. Or would they be fluffier? Discuss #SciFriLive

— Kristine Allen? (@KristineTAllen) March 16, 2018

Stan Love: My vote is fluffier. The carbon dioxide gas in the pancake is going to expand. There’s going to be less gravity making the pancake flat. I think you’re going to end up with nice, fluffy pancakes.

Answers have been edited for clarity and length.

*This tweet had been posted during the radio broadcast on March 16, 2018 but has since been deleted by the user.

Johanna Mayer is a podcast producer and hosted Science Diction from Science Friday. When she’s not working, she’s probably baking a fruit pie. Cherry’s her specialty, but she whips up a mean rhubarb streusel as well.

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.