Is That Really Your Sister Calling?

How hackers and technology will evolve together.

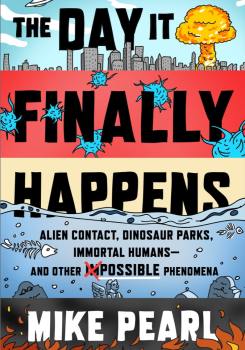

The following is an excerpt of Michael Pearl’s The Day It Finally Happens.

Likely in this century? Inevitable.

Plausibility Rating? 5/5.

Scary? Extremely.

Worth changing habits? Have you not been paying attention to the past twenty years of cybersecurity news? Of course it is!

The call is coming from an unrecognized number. You answer, and the person on the other end of the line is sobbing, but it only takes a split second to recognize your sister’s voice.

“He locked me out! We had a fight and he threw me out. I have nowhere to go!”

You’ve been wondering for months if someone in your family would ever get a call like this. After all, you never liked that guy she is dating, who breeds scorpions for a living.

“Whoa, slow down. Everything’s going to be okay,” you say. “Are you safe?”

There’s a long pause, and then, “I don’t have any friends in Houston! Where am I gonna sleep?”

“Can you get a hotel?”

Another unsettling pause. “With what money?” she asks with a hint of bitterness.

“You don’t have any money?”

“Can you wire me a thousand dollars? Just to get me through the next couple days?”

The Day It Finally Happens

Wire? Can’t she just use Venmo? And anyway, the last you heard, she was doing pretty well at work, and had just bought a car. Then again, Houston is on the other side of the country, and you haven’t been checking in as regularly as you should have.

You tell her you’re going to call your mom and then call her right back.

“Don’t hang up!” she pleads. It’s disturbing—bizarre even—how far she seems to have fallen in such a short time. You hang up.

Before your call to your mom can connect, she’s calling again, on FaceTime now. You answer, bracing for the worst.

You see your sister’s tear-streaked face as she hurries down an empty downtown sidewalk. “His friends know where I am,” she says. “They know what happened, and I’m worried they’re looking for me. I need that money. I’ll be fine if I can get a motel room. I just need a thousand and I’ll pay you right back.”

“Go to the police!” you say.

“I don’t get why you’re making such a big deal about a thousand dollars! You’ve always been like this,” she says, passing through the front door of what looks like a high-tech Western Union. “Look, I’m at the place. I’ll text you the info. Please, just wire me the thousand, and then I’ll go straight to the motel and call you as soon as I’m safe. Okay?”

You’re not rich, but you can afford to part with a thousand dollars if it means keeping your sister safe. “Okay,” you say. “I’m sorry this is happening to you.”

“Thanks,” she says, and a warm feeling of relief washes over you as your sister’s smile returns to her face. “I don’t know what I’m gonna do tomorrow, but I’ll figure it out,” she says. “I love you. I’ll call you right back.”

“I love you, too.”

The text arrives a few seconds later. “This place only converts Bitcoin into cash????” she writes. “But you know how that works, right?” You do, fortunately. You have a few thousand dollars in savings stashed in a Bitcoin wallet.

“Weird,” you text back. “But no problem.”

You transfer the one thousand dollars, and wait for her call.

After fifteen quiet minutes, you FaceTime your mom. When you tell her what happened, she’s furious. “How could he just leave her stranded like that in Scottsdale? They don’t know anyone there!”

“She’s in Houston,” you say.

“No. They’re on vacation in Arizona until Friday,” your mom says. “She just sent me a photo. They went hiking.”

“Well, she FaceTimed with me, so I’m pretty positive she’s in Houston,” you say.

You can hear your father’s voice in the background. “I just texted her. She says she’s in Scottsdale,” he says, before reading the texts aloud. “‘I’m still on vacation. What money?’ ‘LOL. Is she okay?’”

Your face goes red. “I saw her, and she was definitely in Houston!” you shout. You know what you saw. It’s not like you can’t recognize your own sister’s face.

You hang up and text your sister, or at least you text the number your sister was using.

“Hey is everything okay now? Are you at the motel?”

No reply.

“BTW why do Mom and Dad think you’re in Scottsdale?”

No reply.

“What’s going on? Did you get the money?”

Finally you get a reply. It’s an image of that white, goateed mask you’ve seen online. It’s a Guy Fawkes mask, that irritating “Anonymous” symbol.

Then comes a text. “Got it! LOL, thx sis!”

You have an incoming call. It’s your sister, calling from her old number. Her real number, it turns out. In the “INCOMING CALL” notification, your phone displays a picture of her smiling face. Her real face.

You feel your lunch coming back up on you. Not now, you think, and reject it.

The technology referenced in this unfortunate scenario isn’t just some plausible future nightmare; it already exists. In fact, it’s not only real, it’s open source. One free version I’ve found is called FaceIt Live. It allows anyone to send a live video feed of their own face digitally “wearing” someone else’s face like a mask. For now, the results aren’t exactly convincing, but that won’t be the case for long.

Granted, this technology could, say, save you time if you’re a busy actor. On a 2016 episode of the Netflix animated series BoJack Horseman, the eponymous main character had his likeness secretly digitized, and that digital version was used to make an entire film—to much critical acclaim—even though BoJack performed no actual labor. But beyond facilitating fantastic feats of laziness, this technology could also allow you to make convincing videos of the dead, which may sound terrifying but, if used judiciously, might prove a valuable aid in grief counseling. It might also be an amazing—if, once again, somewhat ethically problematic—tool for reconstituting forgotten or suppressed memories.

That ethical stickiness is just the beginning, according to Peter Eckersley, who was chief computer scientist for the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), a digital—rights focused nonprofit at the time I interviewed him, and who is now director of research at the computer industry consortium Partnership on AI. Eckersley’s job at EFF was to be on the lookout for devices and software that might, unbeknownst to users, be violating their civil rights, and he and his team devised software solutions for those potential violations.

So prepare to wake up in a world in which almost anyone can create a truly uncanny fake version of anyone else, who can appear to do anything. Until the darkest imaginations of the general public get their hands on this technology, it’s hard to know just what the applications will be.

The idea of creating convincing computerized imposters has been in the pop culture ether at least since the 1946 short story “Evidence” by Isaac Asimov, about a candidate for public office who’s suspected of being a robot impersonator. The idea became unsettlingly—and realistically—possible when, in 2016, software designers from the Max Planck Institute for Informatics, the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, and Stanford University created a video demonstration called “Face2Face: Real-Time Face Capture and Reenactment of RGB Videos.” With the software, a user could, in real time, capture video footage of someone’s actual face—Russian President Vladimir Putin, say—and then, by pointing a camera at their own face and changing expressions, also real-time, the user could make the target face move however they wanted, though not in a way that was fully convincing.

The demo resembled the Snapchat selfie filters that had been introduced the previous year. Though those were pretty trivial by comparison, they detected faces and could alter them by changing, for instance, the user’s mouth in such a way that it would vomit rainbows. This technology alone was surprisingly sophisticated, but Face2Face was even more advanced. It made it possible for just about anyone to easily and instantly make someone appear to say anything. With this technology, anyone with enough sample images of the face they want to turn into the “mask” and the face that will wear the mask, can hand those photos over to an algorithm, which will then do all the work of swapping the faces. No Hollywood special effects skills required.

“So prepare to wake up in a world in which almost anyone can create a truly uncanny fake version of anyone else, who can appear to do anything.”

The lesson from this demo is that with enough hardware, you can already make anyone look like they’re saying anything, as long as they’re saying it rather stiffly, with nice TV studio lighting, and as long as the viewer doesn’t watch for signs of humanity, like movement of the body.

So what I’m saying is the demo worked amazingly well on politicians and not anyone else.

For the next several months similar technologies were refined, open source tools were applied to the concept, and several ideas converged to allow individuals like you and me (as opposed to researchers in high-tech labs) to produce ever more convincing face swaps. The process became more user-friendly, and digitally mapping any face onto a target face became something anyone with enough devious creativity and time could accomplish.

I suppose what followed was inevitable: in late 2017, a Reddit user with the moniker “deepfakes” superimposed the faces of mainstream celebrities onto the faces of porn performers, generating a series of fake, but unsettlingly realistic (and, importantly, nonconsensual) celebrity sex tapes. It had taken just over a year for the technology to find an application that was, if not overtly illegal, certainly abusive and scummy. Reddit banned the deepfakes community less than two months after journalists had discovered it.

But the term “deepfake” lives on as internet shorthand for videos in which faces are swapped out for other faces, and, as a corollary, face replacement technology has become a microcosm for the scary, “post-truth” future we’re creating for ourselves. In 2018, filmmaker and comedian Jordan Peele appeared in a comedy PSA for BuzzFeed about fake news, in which former president Obama appeared to be saying things like “Stay woke, bitches,” before being revealed as a deepfake, ostensibly perpetuated on the viewer by Peele.

I say “ostensibly” because Jordan Peele doesn’t really sound like Barack Obama when he does his Obama impression, so no one was actually fooled (no offense, Jordan). This voice issue is the biggest obstacle in the way of creating fake videos of people seeming to do things they didn’t really do: they can’t talk. For now.

One day in 2018, I spent a couple hours reading hundreds of sentences into my laptop microphone, and feeding them into a piece of free online software called Lyrebird. Some of the sentences seemed to have been cooked up by a sadistic elocution teacher, like “Science has been arguing about the zoological classification of the species for decades,” and some were rather ominous in the context in which I was being asked to read them, like “Besides encryption, it can also be used for authentication.” Once two hundred or so examples of my unique vocal style were digitized, the software was able to create a text-to-speech engine that generated sentences and phrases that absolutely sounded like me—timbre, inflection, and all.

Well, they sounded exactly like me if my words were being spoken through a desk fan and into a mobile phone, but hearing it was still pretty frightening.

So let’s say someone hacked into my Lyrebird account and used it to leave my girlfriend a voicemail telling her I was a hostage and needed $500,000 transferred into a Swiss bank account. How effective would that be? Well, my Lyrebird avatar is a terrible actor, because it can’t make me sound agitated or scared, so the manufactured voice sounds like me—the real me—calmly reading the words “I’m being held hostage by terrorists, please help.” And no con artist could have possibly fooled my girlfriend with such a recording, because right from the get-go, the voice bombs familiar greetings. “Hello” is too formal, and Lyrebird’s “hey” is way off. And if you call your significant other by a special nickname, like I do, and the con artists aren’t privy to that knowledge, the intended deceit is a non-starter. Even if the tricksters knew the nickname I use for my girlfriend, Lyrebird gets the delivery freakishly wrong.

Eckersley, the computer scientist formerly at EFF, told me that for now, these limitations affect not just Lyrebird, but the more sophisticated versions of this technology that currently only exist in computer labs. “The voices people use while giving public talks are a little different than the ones they use in personal conversation,” which for now affords us some protection, he explained. “But that’s thin protection, and it’s protection that’s going to crumble, potentially, to algorithmic techniques. There’ll be a button that turns on and off the public speaking intonation.” As it gets more robust, presumably, you’ll just hit the emoji that matches the mood you need to hear in the computer voice’s inflection.

You see where this is going: fake phone calls, then fake voicemails, and then fake video calls, not from obvious spammers, but, seemingly, from your loved ones. Maybe the deceivers will ask for your credit card information, but more likely, the ruse will be more clever. As it stands now, you wouldn’t believe a text from a strange number, would you? It’s a safe bet that in the next few years, you won’t be able to believe a similarly strange phone call, or even a Skype call, without trying a little trick such as asking a question only the real person would know the answer to.

Imagining a future when this fakery technology gets in the hands of scammers, let’s say your mom Skypes you while you’re away at college, and says she saw your bank account is getting low, and she wants to transfer you some money, but she needs you to remind her what your account number and routing number are. Don’t buy it—not unless you run your mom’s face through some kind of authentication software, which will either confirm your mom’s identity or unmask the imposter, like at the end of an episode of Scooby-Doo.

According to Eckersley, we need to work on strengthening phone number and email authentication protocols, since the only thing that lets you know to whom you’re speaking is the caller ID, which scammers will easily be able to hack. But he’s not entirely confident that those protection measures will be in place in time to prevent a lot of fraud, since the phone companies have really dragged their heels on computer security protocols.

“You see where this is going: fake phone calls, then fake voicemails, and then fake video calls, not from obvious spammers, but, seemingly, from your loved ones.”

The elderly have been targeted for decades by scams, but as younger baby boomers and Generation Xers hit retirement age in the next few decades, scams will have to become more sophisticated to dupe the tech-savvy elderly, who won’t be so eager to believe that the IRS is calling and needs a cashier’s check right away. But scammers have already found ways to target the next generation of seniors. For instance, they’ve begun using internet dating sites to target the elderly with catfishing scams, pretending to be fellow single seniors looking for love, and then convincing their smitten marks to write checks. Those kinds of scams will become easier, and more prevalent, when anyone can place a Skype call to a senior that seems to prove that the caller is a dreamy—but plausible—potential mate.

When imposter audio and video find a home on sites like YouTube, the implications are even more troubling. The danger then is that, in Eckersley’s words, “the epistemic, or sense-making, fabric that has to some degree held Western society together over at least the past fifty years, if not longer, [will start] to crumble and tear apart.” That may sound overly hysterical, because even perfect fake videos can be proven false with thorough reporting. For example, if a video shows a candidate for office saying something damaging to the candidate’s reputation, reporters will seek out the truth. Was the person really at that place at that time? Is there other footage corroborating this?

But I think we all know by now that journalistic rigor goes out the window when news is spreading online. As is the case with written fake news, concocting a totally wild, out-of-left-field fiction isn’t the ideal way to spread a rumor. Instead, it stands to reason that videos containing a kernel of truth are likely to spread, perhaps videos depicting public figures saying plausible things that fit their public persona.

Imagine a large army of anonymous fake video creators, paid to generate hundreds of plausible-looking videos of a political candidate saying awful things. Yes, that candidate’s enemies might spread the lies, and the public might believe them, but a potentially more unsettling outcome could follow. Assuming the public is aware that a high volume of fake videos exists, they’ll doubt everything they see and hear, whether it’s flattering or unflattering—or even worse, whether it’s true or false. And this is just one political outcome that may or may not come to pass. There’s no doubt that the technology will materialize and spread. When it does, Eckersley told me, “We’re going to find ourselves in a super-weird topsy-turvy world.”

But here’s some good news: this technology will also be harnessed for non-evil.

Face and voice filters for video chat and vlogging, for instance, will allow people to change their faces, so they’ll look and sound not so much like celebrities or innocent people whose identities they’re trying to steal, but rather, just someone else. People who wish to conceal severe craniofacial anomalies, or anyone who might otherwise never feel comfortable on video, could, if they wanted, choose to use something like this to communicate openly and engage in public life.

These technological advances would also allow for the creation of seamless video footage of anonymous witnesses and information leakers in documentaries. Instead of being blurred, pixelated, or cloaked in shadow, these individuals could simply look and sound like a different person—provided the documentarian makes it clear that a disguise is being used.

But, in concluding this discussion, let’s return to lazy actors and digitally resurrecting the dead. The biggest reason to be excited about this incredibly creepy technological frontier is that it will—mark my words—usher in a day when you can create your own custom movies and TV shows with a few keystrokes (or by then, maybe just some hand swipes or blinks).

Let’s say your deepest, darkest fantasy is a slasher movie with Frank Sinatra as the killer, but since Frank is dead, you know you’ll never get to see him wield a bloody chain saw. And now you can! There’s no end to the possibilities for diversion if, you know, things like hiking in the woods, watching sunsets, or petting your dog just aren’t enough.

Excerpted from The Day It Finally Happens by Mike Pearl. Copyright © 2019 by Mike Pearl. Reprinted with permission of Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Mike Pearl is a journalist and author of The Day It Finally Happens: Alien Contact, Dinosaur Parks, Immortal Humans―and Other Possible Phenomena.