Lost And Found In A Museum’s Archive

Specimens from a voyage in 1906 sat in a jar for more than a century, until one scientist named them.

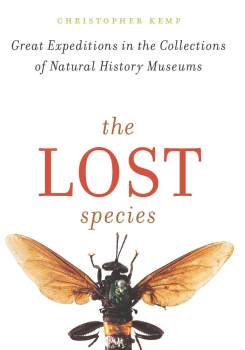

The following is an excerpt from The Lost Species: Great Expeditions in the Collections of Natural History Museums by Christopher Kemp.

On June 4, 1906, the Bering Sea west of Alaska looked gray and hard like granite. A steamship called the USS Albatross was working a grid there, dredging the seafloor off Bowers Bank, a 430-mile submarine ridge that extends northward from the Aleutian Islands before curling westward toward Russia.

The Lost Species: Great Expeditions in the Collections of Natural History Museums

The Albatross was a research vessel owned by the United States Fish Commission. It was the first of its kind, built exclusively as an oceanographic research vessel and launched in 1882. In May 1906 it traveled north from San Francisco and docked at Dutch Harbor, Alaska. In the following months it would complete a circumnavigation of the northwestern Pacific Ocean: from Dutch Harbor westward across the Bering Sea to the Russian Far East, then south to Japan, threading a sinuous course between numerous Japanese islands before heading back to Alaska. Along the way the Albatross stopped at 385 stations to dredge the ocean floor for specimens, collecting hydrographic and meteorologic data at the same time.

On June 4, 1906, at collecting station 4771, the plummet struck the ocean floor near Bowers Bank. It was 7:02 a.m. A half-mile of dark, cold water lay between the ship and the seafloor.

In 2008 Sally Snow (formerly Sally Hall) was partway through a five-week research visit to the Department of Invertebrate Zoology, at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, DC, when she found a large fluid-filled jar. Inside were specimens from collecting station 4771. The contents were uncataloged: still unknown. Snow is a carcinologist—she studies crabs—and she was at the Department of Invertebrate Zoology to explore its extensive collection of king crab specimens. “I was doing an audit of their collections,” she says, “looking at all the crabs within this particular family—Lithodidae.”

For several weeks Snow, then a student at the National Oceanography Centre in Southampton, had been retrieving specimens of large decapod crabs from the collection and measuring them, building an array of precise measurement data for her dissertation. By comparing closely related crab species, she hoped to reveal how different species adapt to their habitats, particularly in relation to depth. “I was taking a specific set of measurements,” she says, “particularly on the leg aspect ratios but also aspects of the carapace and how they were ornamented.”

Snow had already crisscrossed the world visiting scientific collections to measure crab specimens: the Natural History Museum in London; the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris; the Museum Koenig in Bonn; the Naturmuseum Senckenberg in Frankfurt; the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research in Bremerhaven, Germany; and other large invertebrate collections in Madrid and Vigo.

But now, at the Smithsonian Institution, she says, “They had large jars of unidentified species. Either they were identified to family level, so they had a label that said ‘Lithodidae’ and the collection details, or it just said ‘Unidentified.’” The specimens from Bowers Bank, Snow says, belonged to a species she didn’t recognize. She picked up a single specimen, its legs dangling limply from its carapace. At this time Snow had measured several thousand crab specimens. “I’d already been working on this research for about two and a half years, so I immediately knew it was a new species,” she tells me. “It didn’t look like anything I’d ever seen before.”

By then, she estimates, she was one of only ten people in the world who could identify the specimens as examples of a novel species just by looking at them. Snow named the new species Paralomis makarovi after V. V. Makarov, who wrote a seminal 1938 paper on the biogeography of lithodid crabs. Morphologically, she says, the crab resembles a ball of spines. Every part of its compact body—its small, pear-shaped carapace and its legs, tucked neatly beneath it— bristles with spines. And each conical spine is covered with setae— a coat of stiff, hairlike fibers. The specimens are mostly pale pink, legs faded white like bone. “Based on other members of the family that live at that depth, I suspect they were dark pink or orange when alive,” says Snow.

[In Wyoming, your canvas tote bag could be used for more than carrying your belongings…]

The crab belongs to a large family: the Lithodidae. About 107 species are known currently, in ten genera, and they are found in a range of habitats and ranges, mostly pitch-black, abyssal, deepwater environments. Technically lithodids are not considered true crabs, Brachyura; they’re more closely related to hermit crabs.

The lithodids remain mysterious. The great depths where they live make them difficult to study. Another species, Paralomis bouvieri, has been found at depths of 4,152 meters, more than two and a half miles deep, where it’s almost impossible to study its natural history. In fact, P. makarovi doesn’t look much like a typical lithodid at all. First, it’s small. Many king crab species have earned their names: they grow to enormous sizes. Paralithodes camtschaticus—the red king crab—is a heavily harvested species also found at Bowers Bank, sharing its range with P. makarovi and several other lithodid species. Its broad rust-colored carapace is ornamented with rough nodules, covered and ridged with tubercules and knobby protrusions. The carapace of a large old P. camtschaticus specimen can be almost a foot across—the size of a hubcap. It has a six-foot leg span, more typical of lithodids. “I was used to looking at massive crabs,” says Snow.

In contrast, P. makarovi measures about ten centimeters across at its widest point. It fits comfortably in Snow’s palm like a pale, bristly disk. When she first saw the specimens in the jar, she suspected they were juveniles of an already known lithodid species. As they develop into adults, crabs change a lot in appearance, Snow says, so she asked researchers she knew in Alaska if they had seen crabs like the specimens in the collection. They had, they told her, but the species had not been described. It had no name. “King crabs have been known for a long time. To find something that was so different from anything already known was very exciting.”

In her paper published in Zootaxa in 2009, Snow described three more novel species too: Paralomis alcockiana, from South Carolina; Paralomis nivosa, from the Philippines; and Lithodes galapagensis, from the Galápagos archipelago. She found the holotypes of them all at the National Museum of Natural History. P. nivosa had spent almost as long on the shelf as P. marakovi. It was collected in December 1908, near Palawan in the Philippines, during a subsequent voyage of the Albatross.

Reprinted with permission from The Lost Species: Great Expeditions in the Collections of Natural History Museums by Christopher Kemp, published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2018 by Christopher Kemp. All rights reserved.

Christopher Kemp is a scientist and the author of The Lost Species: Great Expeditions in the Collections of Natural History Museums.