What Coastal Retreat Looks Like On Isle de Jean Charles

On an island shrinking from rising seas, Indigenous communities battle to save their historic land from coastal flooding.

This story is a part of our fall Book Club conversation about ‘Rising: Dispatches From the New American Shore.’ Want to participate? Join our online community space or record a voice message on the Science Friday VoxPop app.

The following is an excerpt from Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore by Elizabeth Rush.

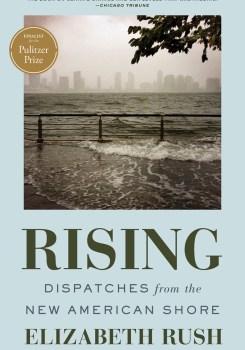

Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore by Elizabeth Rush

Chris Brunet: Isle de Jean Charles, Louisiana

As far as changes go since the last time you were down here, well, for one, I’m bald. But really the biggest change is that it looks like the relocation of the community of the Isle de Jean Charles will happen. Through HUD [the Department of Housing and Urban Development] and the Lowlander Center, Albert, our tribal chief, got $48 million set aside to help us move. As you know, Albert has been pushing for relocation for the last sixteen years. All the other times, the place they wanted us to go was unacceptable. Or else there was not enough money to really do all that much. But finally with this try here it looks like it’s going to work. With this grant we have more freedom and more choices, which is to our favor. The more choices you’ve got in any kind of change the better off you are.

The relocation project is going to be a community development. It’s going to be the rebirth of the community of the Isle de Jean Charles. But we don’t know where just yet. We already had two meetings with HUD, where they called the island people together at the Montegut gym. They wanted to find out what it is that we wanted. I am so glad they did that because surprisingly so many good ideas came out of those meetings. Some brought up: What kind of drainage are we going to have? Some brought up: What kind of playgrounds are we going to have? We even brought up the idea of a fishing pond because we want to have the same kind of life over there that we have here. Mostly we want to be as close as possible to the island and not in the city.

Over the years, with the hurricanes and the land loss and the flooding, many people have been displaced. It got to the point that if something wasn’t done then eventually there would be no Native community, no more people of the Isle de Jean Charles. Many of those that left, it looks like they’re going to be included too, and I think for them especially this relocation can do some good. The island is already a skeleton of its former self and that’s what’s happening inside the community as well. When we relocate to higher ground we will at least be able to hold on to each other. I mean if we can stay together, then we won’t have lost as much.

I’ve shared that thought with others, but saying it again to myself and to you right here, it is like, yeah, that makes sense. I mean really we are talking about having to choose to move away from our ancestral home. I know a lot of people figure we would be celebrating, to be moving to firmer ground and all. But it’s not like I threw a party when I heard about the relocation. I’ll be leaving a place that has been home to my family for right under two hundred years. I go all the way back to the island’s namesake, Jean Charles Naquin.

Those of us out here are so tied into the Isle de Jean Charles. It’s all we have known for the last eight generations. I spend most of my days right here. You know I am Choctaw, Native American. For us moving is not just about getting up and making a career move. We’re actually leaving the place where we belong.

But what is the future of the island? Me, I know I could finish off my life on Jean Charles. I’m fifty-one years old. But then what about the next generation, those kids that are teenagers today? What about my niece and nephew, Juliette and Howard? I think about them at my age. I mean what is going to happen between now and then? In less than one hundred years, saltwater intrusion has taken away so much of the island. You are talking about an area that used to be eleven miles long and five miles wide. Now it’s two and a half miles long and a quarter mile wide. So when I choose to be part of the relocation I’m making a decision today for tomorrow. I’m not making the decision out of desperation. I’m not making the decision out of fear. I’m just uncertain about what is to come. And I’m trying to take advantage of my chances while I have them.

I guess at the moment, I don’t know what to say. I’m not having a great difficulty thinking about tomorrow today. It’s not throwing me into a big confusion. But to arrive at this decision isn’t easy. I don’t know if I can offer any lesson to other people in the same or similar situations. Maybe the only thing you can learn from me would be to try to see your life so many years down the road, and if you see trouble, if you fear you’re going to have too much against you, if the water is going to keep on rising, then it might be a good time to go.

Right here from where I am sitting down, I’m going to count off… one, two, three, four… five… six, seven, eight, nine, ten, eleven… twelve, thirteen, fourteen… fifteen. Fifteen trees. Gone. You can’t even see the stumps of some of them no more. Right there, right on the other side of the road. There was a time you could walk between these two big oak trees and the branches would cross over and the Spanish moss would hang down and it looked like you were under an archway.

You could say once the salt started to get into the water table, that was when everything started to die. But it was a gradual process. Now, today, we see we done lost so much. We can only say that in the present though, because back when it was starting we really didn’t know. It has got me thinking: What is the definition of the coast? What is coastal Louisiana? If everything is shut down here, what is Louisiana doing being the “Bayou State”? What is it that makes Louisiana the sportsman’s paradise? Where is it that people will go whenever they leave up north to come down here and see the beauty of Louisiana?

I am sitting here, a coastal resident surrounded by water and coastal erosion. I am moving in. I know for myself that no matter what kind of technology they possess they cannot bring it back to what it was. There is no way to recreate Louisiana’s coast, all the bayous and lakes, all the shrimping and the crabbing, and the other animals that lived out here. But if something can be done to slow down the tide and they can save what they still have, they should do it. If you come right down to it, we are all up against coastal erosion. We are all impacted by it. It has taken the island away from us, and in the future it is going to take other places as well. I may be uncertain about a lot of things, but not about this here.

From Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore by Elizabeth Rush (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2018). Copyright © 2018 by Elizabeth Rush. Reprinted with permission from Milkweed Editions. milkweed.org.

Elizabeth Rush is the author of Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in General Nonfiction, and Still Lifes from a Vanishing City: Essays and Photographs from Yangon, Myanmar. Her work explores how humans adapt to changes enacted upon them by forces seemingly beyond their control, from ecological transformation to political revolution.