Searching For Sakura

Collingwood Ingram became enamored of Japan’s cherry blossoms during his honeymoon. He would devote his career to saving them.

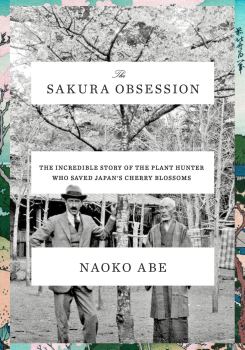

The following is an excerpt of The Sakura Obsession by Naoko Abe.

High in Japan’s mountains, away from industrial pollution and human interference, most of the original wild-cherry species of Japan appeared to be thriving. Better still, when Ingram arrived at Hakone, a city two hours west of Tokyo by train, on 26 April 1926, the wild Fuji cherry was in full bloom. As Ingram strode up the mountains above Lake Ashi, to the west of Hakone, he noticed that the vivid red of the outermost petals blended with the white of the inner petals to produce a soft pink effect. About 1,800 feet above the lake, he could see in the distance the reddish leaves and white flowers of the most common wild species, Yama-zakura, which created a similar satisfying pink result. On a slope leading to the town of Odawara, about five miles northeast of Hakone, Ingram spied “fine, upstanding” Yama-zakura.

The Sakura Obsession: The Incredible Story of the Plant Hunter Who Saved Japan's Cherry Blossoms

His pilgrimage continued on horseback several days later. An experienced rider since his youth in Westgate-on-Sea, Ingram meandered slowly along 18 miles of narrow, winding forest paths from Lake Shōji, one of five lakes near Mount Fuji, to Fujikawa, a small town to the north-east.

Each turn on the precipitous slopes brought unexpected thrills: a glorious mauve azalea; a towering pile of blossoms on a Sargent cherry tree; an old, time-twisted pine; a snowy crabapple; a lilac-flowered wisteria sprawling down a rocky cliff. And yet more Sargent cherries. These trees, he wrote, “were growing on a distant slope, beyond the shadowed depths of an intervening valley—glorious symbols of spring in the midst of a wintry landscape. To complete the picture, the mysterious and mighty cone of Mount Fuji, with its inevitable diadem of clouds, towered to an incredible height in the background, dominating the whole scene.”

In his diary and in later narratives, Ingram wrote about that day—Thursday, 6 May 1926—with awe and deep emotion:

Viewed against the dazzling blue of the sky, the trees’ flower-laden boughs seemed as though illumined by a soft glowing light—rosy-hued like the tint of dawn-flushed snow. Even the trunks and branches were things to admire. Naturally glossy, where a shaft of sunlight fell upon their surface, they were transformed into glistening columns of burnished bronze.

Here and there, in the pit of the hollows, the eye could make out a nestling, thatched-roofed village, set about with green terraced fields. But the huddled, fantastically steep mountains claimed the landscape, and man was here a mere incident. For long I sat and let the beauty of the scene soak into my soul.

This transcendental moment was heightened by the melding of Ingram’s two great passions—birds and blossoms:

As I stood there, spellbound, I heard a sudden, almost startling, outburst of melody from a nearby grove of bamboo. Somewhere out of the bosky gorge rose the muffled notes of a dove and then the loud, long-drawn liquid pipe of the ‘uguisu,’ the little russet-coloured nightingale of Japan, ending with a strange, sudden flourish. It would be difficult to conceive a more fitting association of sight and sound in the heart of that vast and lonely forest.

Weeks into his trip, when Collingwood Ingram arrived in Nikko, 95 miles due north of Tokyo and 4,000 feet above sea level, thick snow enveloped the city. The woodlands here were as stark and bare as in midwinter. In September 1902, on his first visit to Japan, Ingram had been entranced by this city’s Buddhist temples and by the mausoleum of Ieyasu Tokugawa and his grandson, Iemitsu, the first and third shōguns of the Tokugawa shogunate. This time, after a brief visit to the temples, he hiked through the leafless woods in search of blooming cherries. His hiking partner was Ishiguro Suzuki from the Yokohama Nursery, a plump man with a fixed smile who was wearing a European city suit.

The men walked for miles along mountain tracks and beside a swollen river, before entering a dense deciduous forest. On a mountain ridge at about 2,000 feet, Ingram was suddenly spellbound. In front of him was a superlative specimen of a Sargent cherry “in its full vernal glory, with every bough and every twig wreathed in soft shell-pink blossom.” When Ingram dashed off to collect some tiny seedlings, he lost Suzuki. But he gained a superb cherry, which grew for years in a corner of his croquet lawn at The Grange.

On a separate walk from Nikko to the picturesque Lake Chūzenji, 15 miles west of the city, Ingram collected more Sargent seedlings to take back to England and found an ancient specimen with unusually large flowers at about 2,500 feet above sea level. Next on the list was a visit to an avenue of healthy, evenly matched and wide-spreading Somei-yoshino cherries in Utsunomiya, east of Nikko. Despite their ubiquity, Ingram still appreciated the “floriferous and beautiful” trees, in the same way that a dog-lover would still love a Labrador even if the majority of dogs in the world came from that one breed.

“Viewed against the dazzling blue of the sky, the trees’ flower-laden boughs seemed as though illumined by a soft glowing light—rosy-hued like the tint of dawn-flushed snow. Even the trunks and branches were things to admire.”

From Utsunomiya, Ingram travelled more than 200 miles north by car to the pine-clad islets of Matsushima Bay on Japan’s east coast, where he hired a motor boat and drifted out to sea for a few miles. There, looking back at Matsushima village through his binoculars, he spotted a solid mass of rosy- pink on one side of a whitish cloud of Somei-yoshino cherries. Excited by the unusual sight, Ingram rushed back to shore, to discover one of the most magnificent and largest Edo-higan wild cherry trees he had ever seen. Planted on an incline next to a small deserted shrine, the tree was at least 40 feet high with an 18-foot girth at its base. “Every twig was closely packed with blossom–the individual flowers being of relatively good shape and size,” he wrote. “I have rarely seen a more beautiful object.”

Out in the countryside, away from the cities, Ingram was on a roll. In the straggling village of Kami Yoshida, for instance, at the foot of Mount Fuji, he made one of his most exciting discoveries. There, in the garden of a house near the Osakabe Hotel, towering above a tall wooden fence, stood a tree with narrow leaves and bunched clusters of double mauve-pink blossoms with close to 100 petals. It resembled a cherry that E.H. Wilson had described in 1913, but was clearly a different variety. Nor was it included in Professor Miyoshi’s classification guide. Ingram’s immediate reaction was to work out how to spirit cuttings of the tree to England.

Fate was on his side. Nineteen years earlier, on his honeymoon, he had visited this very village while hunting birds, and he remembered meeting there a one-legged war hero whose parents ran the Osakabe Hotel. That man, who had lost a limb during the Russo-Japanese War, was still alive, a villager told Ingram. Indeed he was now running the hotel. And his hobby was gardening! In typical Ingram fashion, he convinced the innkeeper to send him scions from the tree, in exchange for one yen to cover the postage. By 1929 a couple of sturdy offspring were growing in Benenden.

Ingram dubbed the plant Asano, after the hero of the Forty-Seven Rōnin saga. The story was that in April 1701 a daimyō from western Japan, Naganori Asano, had been ordered by the fifth Tokugawa shōgun, Tsunayoshi Tokugawa, to commit ritual suicide, or hara-kiri, after wounding an envoy from the imperial family in Edo Castle because he thought he had been insulted. In revenge, forty-seven of Asano’s samurai retainers, now leaderless and known as rōnin, decided to kill the envoy themselves. They were caught and also slit their bellies. In the kabuki play about the incident, Chūshingura, Asano’s final act was to read the death poem that he wrote before committing hara-kiri:

More than the cherry blossoms

Inviting a wind to blow them away

I am wondering what to do

With the remaining springtime.

Although Ingram never said why he called this particular cherry Asano, it probably reflected his interest in samurai stories. Today the Asano cherry is a popular variety in Britain and forms the centrepiece of the Asano Avenue at Kew Gardens in London.

Excerpted from The Sakura Obsession by Naoko Abe. Copyright © 2019 by Naoko Abe. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Naoko Abe is author of The Sakura Obsession: The Incredible Story of the Plant Hunter Who Saved Japan’s Cherry Blossoms (Knopf, 2019). She’s a former journalist at the Mainichi newspaper, and is based in London, England.