The ‘Murderous’ Medical Practice Of The 18th Century

For centuries, people thought mercury was a safe, easy remedy for everything from melancholy to syphilis.

The following is an excerpt from Quackery: A Brief History of the Worst Ways to Cure Everything by Lydia Kang and Nate Pedersen.

Of Roman Gods, Toilet Archeology, Drooling Syphilitics, an Immortal Wannabe, and Erroneous Snakes

The baby’s hands and feet had become icy, swollen, and red. The flesh was splitting off, resembling blanched tomatoes whose skins peeled back from the fruit. She had lost weight, cried petulantly, and clawed at herself from the intense itching, tearing the raw skin open. Sometimes her fever reached 102 degrees.

“If she was an adult,” her mother had noted, “she would have been considered to be insane, sitting up in her cot, banging her head with her hands, tearing out her hair, screaming, and viciously scratching anyone who came near.”

Quackery: A Brief History of the Worst Ways to Cure Everything

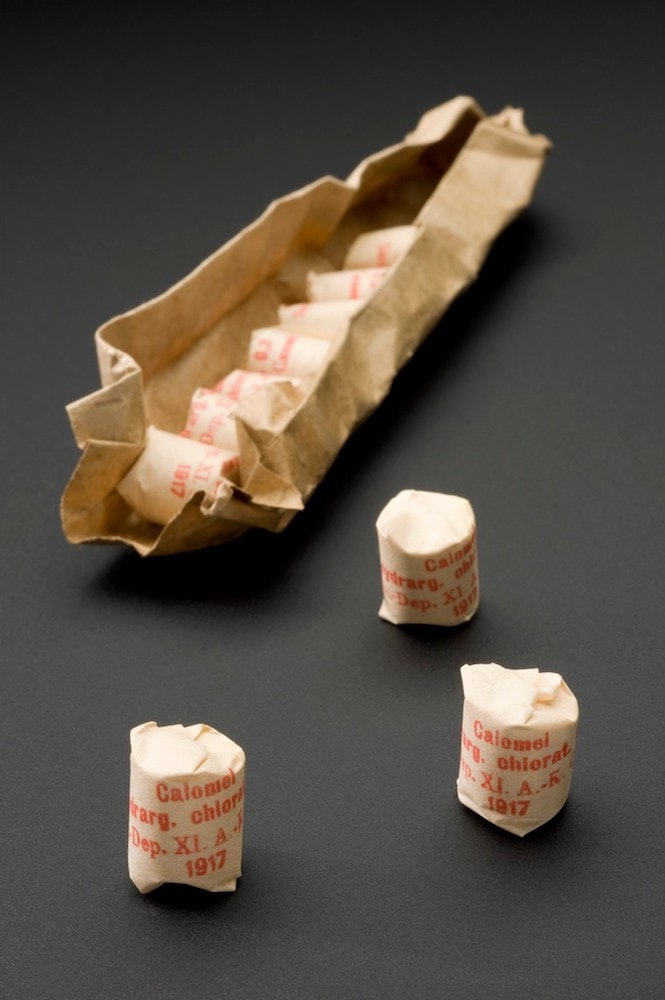

Later on, her condition would be called acrodynia, or painful tips, named so for the sufferer’s aching hands and feet. But in 1921, they called the baby’s affliction Pink’s Disease, and they were seeing more and more cases every year. For a while, physicians struggled to determine the etiology. It was blamed on arsenic, ergot, allergies, and viruses. But by the 1950s, the wealth of cases pointed to one common ingredient ingested by the sick kids—calomel.

Parents, hoping to ease the teething pain of their infants, rubbed one of many available calomel-containing teething powders into their babies’ sore gums. Very popular at the time: Dr. Moffett’s Teethina Powder, which also boasted that it “Strengthens the Child . . . Relieves the Bowel Troubles of Children of ANY AGE,” and could, temptingly, “Make baby fat as a pig.”

Beyond the creepy promise of Hansel and Gretel-esque results, there was something else sinister lurking within calomel: mercury. For hundreds of years, mercury-containing products claimed to heal a varied and strangely unrelated host of ailments. Melancholy, constipation, syphilis, influenza, parasites—you name it, and someone swore that mercury could fix it.

Mercury was used ubiquitously for centuries, at all levels of society, in its liquid form (quicksilver) or as a salt. Calomel—also known as mercurous chloride—fell into the latter category and was used by some of the most illustrious personages in history, including Napoleon Bonaparte, Edgar Allan Poe, Andrew Jackson, and Louisa May Alcott. Why? That’s a longer story.

Drawing from the Greek words for good and black (named so for its habit of turning black in the presence of ammonia), calomel was the medicine from the sixteenth to the early twentieth century. Despite what it sounds like, calomel is nothing like caramel, though it sometimes carried the stomach-churning monikers “worm candy” and “worm chocolate” for treating parasites. By itself, calomel seems fairly innocuous—an odorless white powder. But don’t be fooled: It’s as harmless as your khaki-clad next-door neighbor who hides a basementful of bone saws. Taken orally, calomel is a potent cathartic, which is a sophisticated way of saying it will violently empty out your guts into the toilet. Constipation had long been associated with sickness, so opening the rectal gates of hell was a sign of righting the wrongs.

Some believe the “black” part of its name evolved from the dark stools ejected, which were mistaken for purged bile. Allowing bile to “flow freely” was in harmony with keeping the body balanced and the humors happy, a theory that harkened back to the time of Hippocrates and Galen. And if the insides of the bowels were dark and slimy, wasn’t it better to rid the body of such toxins?

The “purging” occurred elsewhere, too—in the form of massive amounts of unattractive drooling, a symptom of mercury toxicity. A calomel consumer could give a rabid dog a run for its money. If the bad stuff was expelled via copious salivation, that was good, right? In the sixteenth century, Paracelsus believed that “effective” (i.e., toxic) doses of mercury were achieved when at least three pints of saliva were produced. That’s a helluva lot of spit. And so, at a time when overflowing privies and gallons of loogie were the answer to a multitude of ailments, physicians found their drug of choice in calomel.

Benjamin Rush was one such physician. A founding father who signed the Declaration of Independence, Dr. Rush advocated for women’s education and the abolition of slavery. He pioneered the humane treatment of psychiatric patients, but unfortunately thought that mental illness was best treated with a dose of calomel. He suggested this for the treatment of hypochondria:

Mercury acts in this disease, 1, by abstracting morbid excitement from the brain to the mouth. 2, by removing visceral obstructions. And, 3, by changing the cause of our patient’s complaints and fixing them wholly upon his sore mouth. The salivation will do still more service if it excite some degree of resentment against the patient’s physician or friends.

Resentment against your doctor and BFF is a fantastic side effect! But in truth, Rush was replacing hypochondria with heavy metal toxicity. Another side effect was mercurial erethism, a neurological disorder that includes depression, anxiety, pathological shyness, and frequent sighing. Together with tremors of the limbs, these symptoms were often called mad hatter’s disease or hatter’s shakes (for the hat-making workers who used mercury in the felting process). In addition, toxic patients could suffer from lost teeth, rotting jaw bones, and gangrenous cheeks that produced facial holes, exposing ulcerated tongues and gums. Okay, so what if success meant that Rush’s patients turned into extremely moody Walking Dead extras?

When the mosquito-borne Yellow Fever virus hit Philadelphia in 1793, Dr. Rush became a passionate advocate of extreme amounts of calomel and bloodletting (“heroic depletion therapy”). Sometimes, ten times the usual calomel dose was employed. Even the purge-loving medical establishment found this excessive. Members of the Philadelphia College of Physicians called his methods “murderous” and “fit for a horse.” Earlier, in 1788, author William Cobbett had labeled Rush a “potent quack.”

At the time, Thomas Jefferson estimated the Yellow Fever fatality rate at 33 percent. Later, in 1960, the fatality rate of Rush’s patients was found to be 46 percent. Not exactly an improvement on the status quo.

Ultimately, it was Dr. Rush’s influence on improving Philadelphia’s standing water problem and sanitation—plus a good, mosquito-killing first frost of autumn—that ended the epidemic. Alexander Hamilton, a friend of Dr. Rush, had become ill himself, but turned to another doctor who employed gentler methods. “In his theory of bleeding and mercury,” Hamilton wrote, “I was ever opposed to my friend . . . whom I greatly loved; but who had done much harm, in the sincerest persuasion that he was preserving life.” Hamilton survived, but Dr. Rush’s reputation didn’t. By the turn of the century, his medical practice dwindled to nothing.

Still, calomel continued to be used. It wasn’t until the mid-twentieth century that mercury compounds finally fell out of favor, thanks to a solid understanding that heavy metal toxicity was actually, you know, bad.

Excerpted from Quackery: A Brief History of the Worst Ways to Cure Everything by Lydia Kang, MD and Nate Pedersen (Workman Publishing, 2017) ©. Used with permission.

Lydia Kang is an assistant professor of general internal medicine at the University of Nebraska Medical Center and co-author of Quackery: A Brief History of the Worst Ways to Cure Everything (Workman, 2017). She is based in Omaha, Nebraska.

Nate Pedersen is a librarian, historian, and writer based in Oregon. He is a co-author of Quackery: A Brief History of the Worst Ways to Cure Everything (Workman, 2017).