The Origin Of The Word ‘Alcohol’

“The cause of (and solution to) all life’s problems” is derived from Arabic. But the word ‘alcohol’ originally referred to a method of manufacturing makeup, among other things.

Science Diction is a bite-sized podcast about words—and the science stories behind them. Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts, and sign up for our newsletter.

Science Diction is a bite-sized podcast about words—and the science stories behind them. Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts, and sign up for our newsletter.

Like many words in science that begin with al-, “the cause of (and solution to) all life’s problems” is derived from the Arabic al-kuhul or al-kohl. But the term originally referred to a method of manufacturing makeup (among other things).

People have been making—and drinking—alcohol for nearly as long as human history. Residue from a beerlike, 13,000-year-old fermented drink was recently unearthed in Israel, and evidence of a fermented drink of rice, honey, and fruit discovered in China dates to 7000–6600 BCE. But how did we come up with a name for those drinks that make us feel so nice and fuzzy?

We want to be upfront here: Like the result of over-imbibing, this scientific origin story is a bit hazy. Few primary sources remain, and the tale has almost certainly been storified over the centuries.

In the first century, CE, Alexandria, Egypt, was thriving. The city was a hotbed of intellectuals and academics, providing an ideal setting for scientific innovation.

“It’s a science city, it’s an academic city, there’s universities and labs and [the famous library],” says Adam Rogers, author of the book Proof: The Science of Booze. “And there’s a woman named Maria the Jewess.”

We don’t know much about Maria; much of the tale blends the historical with the mythical.

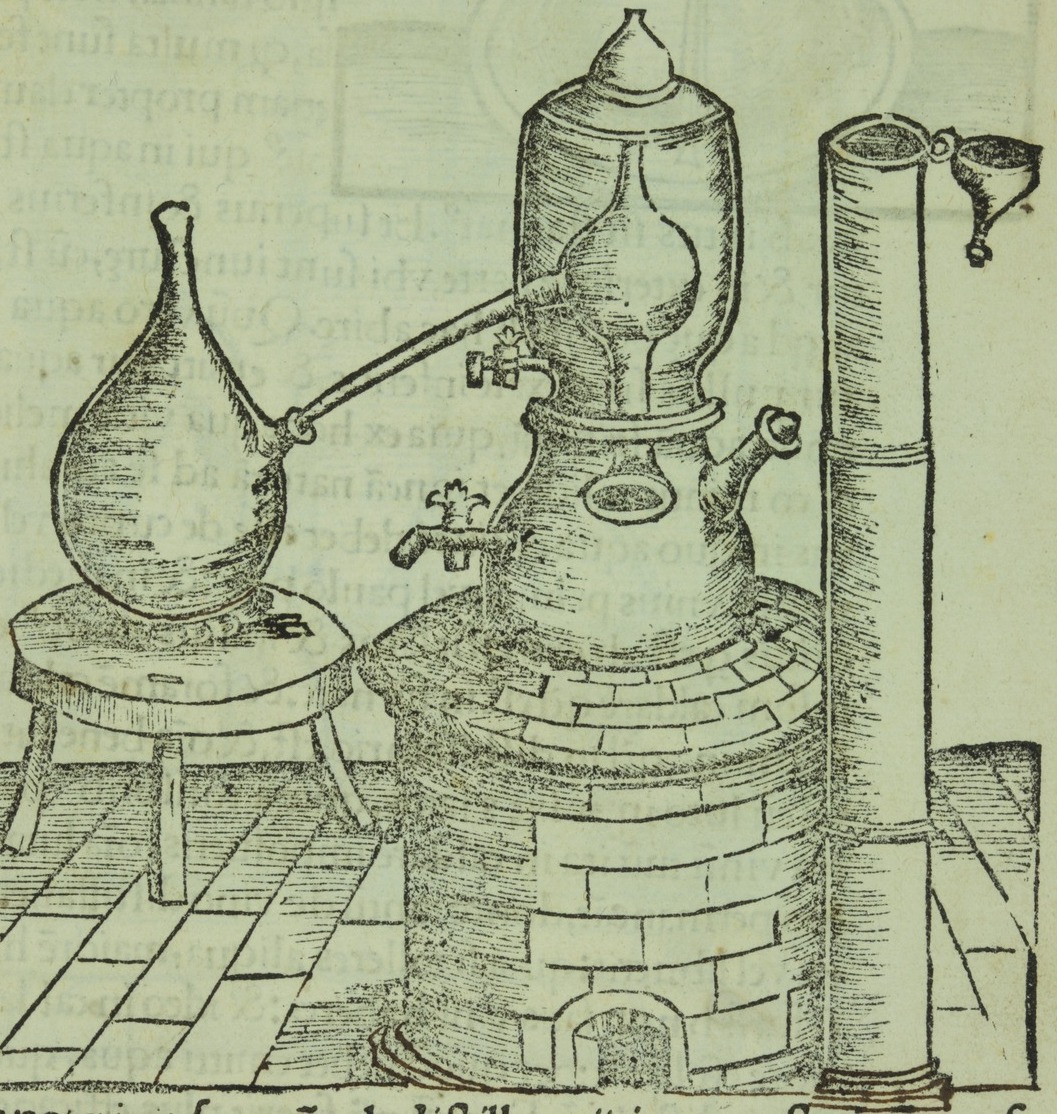

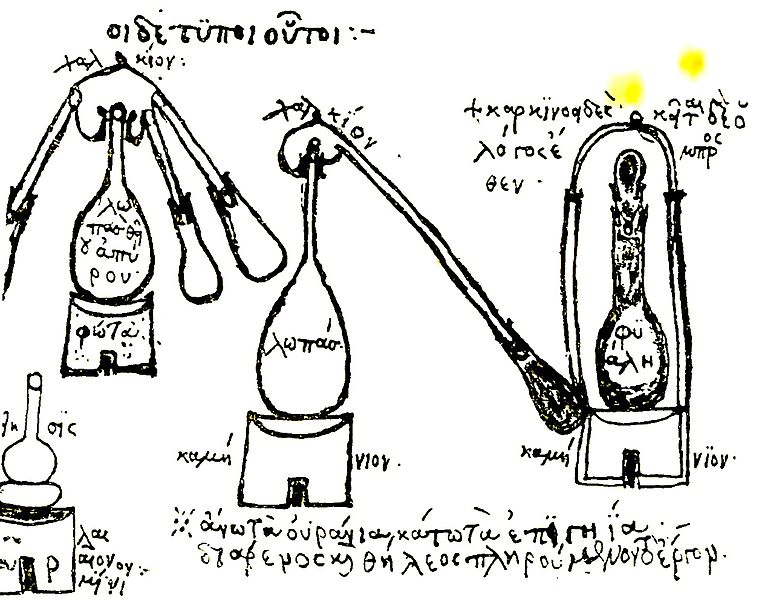

The story goes that she was an alchemist, a professor, a lab operator, and, perhaps most significantly, an inventor. As an alchemist, she “tirelessly” tried to transmute base metals into gold. One of the key stages of that process was distillation. Maria is said to have perfected that process by inventing some of its key tools: the bain-marie, or the double boiler, as well as a version of a still.

[Are non-native species all that bad, or are we just prejudiced against “the Other”?]

Rogers explains that her version cooked a substance, which allowed the resulting vapors to rise, move through an arm, then re-condense into a liquid.

But, he says, “they probably aren’t using that in Alexandria to make a drink. They’re probably using it to figure out what sulfur is and what mercury is.”

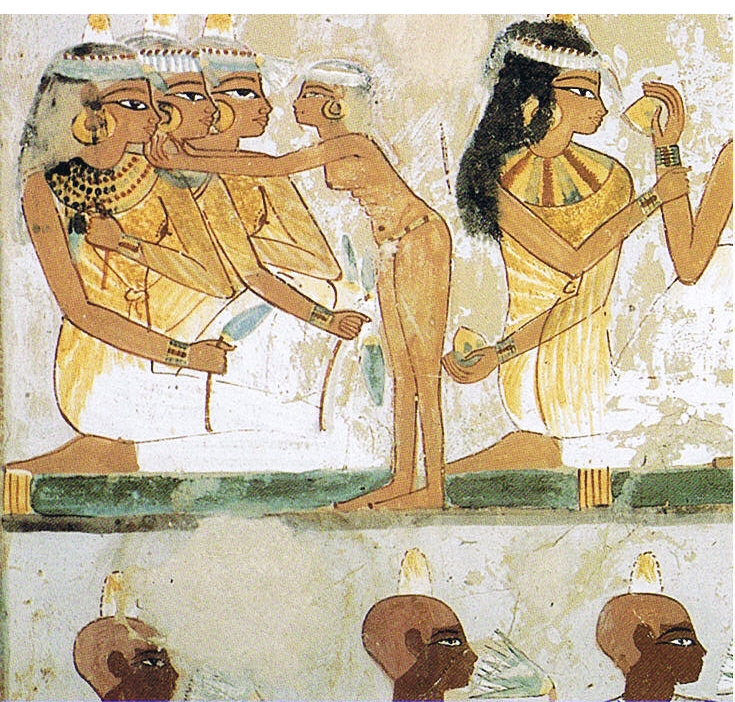

It was a version of this technology that the Ancient Egyptians would use to enhance their characteristic kohl eyeliner. They had been painting their eyes for centuries with the dark, thick, pigment that was made from grinding up carbon compounds. In a 2009 study published in Analytical Chemistry, researchers found that the kohl was primarily a mixture of four chemicals: galena, cerussite, laurionite, and phosgenite. (It’s likely they also used stibnite and malachite.) When the early distillation technology from Alexandria eventually spread, the Egyptians began to distill manganese ore to conjure even more intense forms of the makeup. And while the eyeliner frequently led to lead poisoning, researchers also found that it acted as a toxin, zapping infections that arose and entered via the eyes when the Nile flooded.

Alexandria, a major trade center at the end of the Silk Road, was primed to spread knowledge. “You can imagine the things that get invented there disseminating and spreading across trade routes,” says Rogers. “The idea is that once you have a still that you can do chemistry with and you can make some substances into others, then that’s kind of how they’re making the kohl makeup and a whole bunch of other powders that they’re using for similar means. And then al-kohl becomes kind of a catch-all term for the technology.”

According to Merriam-Webster, when alcohol first appeared in English, it was used to describe kohl and other such powders; it didn’t describe booze until the 18th century.

And while it was likely specific technology that gave booze the name we use today, the underlying technology—fermentation and distillation—has been around since antiquity. Even Aristotle wrote in Meteorologica about distilling seawater. But “there aren’t any good histories of distillation,” says Patrick McGovern, scientific director of the Biomolecular Archaeology Project at the University of Pennsylvania Museum. “That is sort of a gap in our knowledge.”

[Making a hard cider is about 50% chemistry. The other 50% is art.]

Some clues have sprung up across the world. “Although much controversy still swirls around how distillation began in east Asia and whether it was independently discovered there, this region has yielded the best and earliest archaeological evidence for distillation,” McGovern says. He’s referring to a bronze distillation apparatus unearthed in China dating back to the Eastern Han Dynasty, from about 25 to 220 CE. The vessel, which contains a double rim and a small spout, could’ve been used to make medicines, perfumes, and, of course, rather strong beverages, he says.

Other evidence points to a rise in distillation in the Middle East. The earliest distillation apparatus from that region, says McGovern, is quite different from the one found in China—it featured a flask with a long, downward-pointing neck on top of a heat source. The Egyptian alchemist Zosimos of Panopolis, who lived around 300 CE and wrote about Maria the Jewess, is said to have created the first accurate illustrations of the device. It’s not clear whether Zosimos or Maria—or both—was directly responsible for this version of the apparatus, but it was this iteration that snaked up into Europe and was passed along by medieval Arab scholars, explains McGovern. Exactly when that transfer occurred is, to the best of our knowledge, unclear.

The reason the technology did spread, though, is much more clear. “Alcoholic beverages are usually at the center of all the cultures we know of, going back as far as we can go,” says McGovern. “These beverages have been very much a part of human culture.”

Alcohol kills bacteria and preserves food. Culturally, it’s usually a center of social life. It features prominently in certain religions. Biologically, alcohol is a source of energy—10 percent of the enzymes in our liver are devoted to converting alcohol into energy, says McGovern. And of course, alcohol is important economically.

“New World wine and craft beer movements and so forth, those are just the latest manifestation of how popular and desired these beverages are,” McGovern says. “That’s what I’ve come to find out as we do this research and chemical analyses—alcoholic beverages are really very tied into human culture historically.”

Johanna Mayer is a podcast producer and hosted Science Diction from Science Friday. When she’s not working, she’s probably baking a fruit pie. Cherry’s her specialty, but she whips up a mean rhubarb streusel as well.