The Origin Of The Word ‘Quark’

It’s a tale of particle physics, Aristotle, and James Joyce.

Science Diction is a bite-sized podcast about words—and the science stories behind them. Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts, and sign up for our newsletter.

Science Diction is a bite-sized podcast about words—and the science stories behind them. Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts, and sign up for our newsletter.

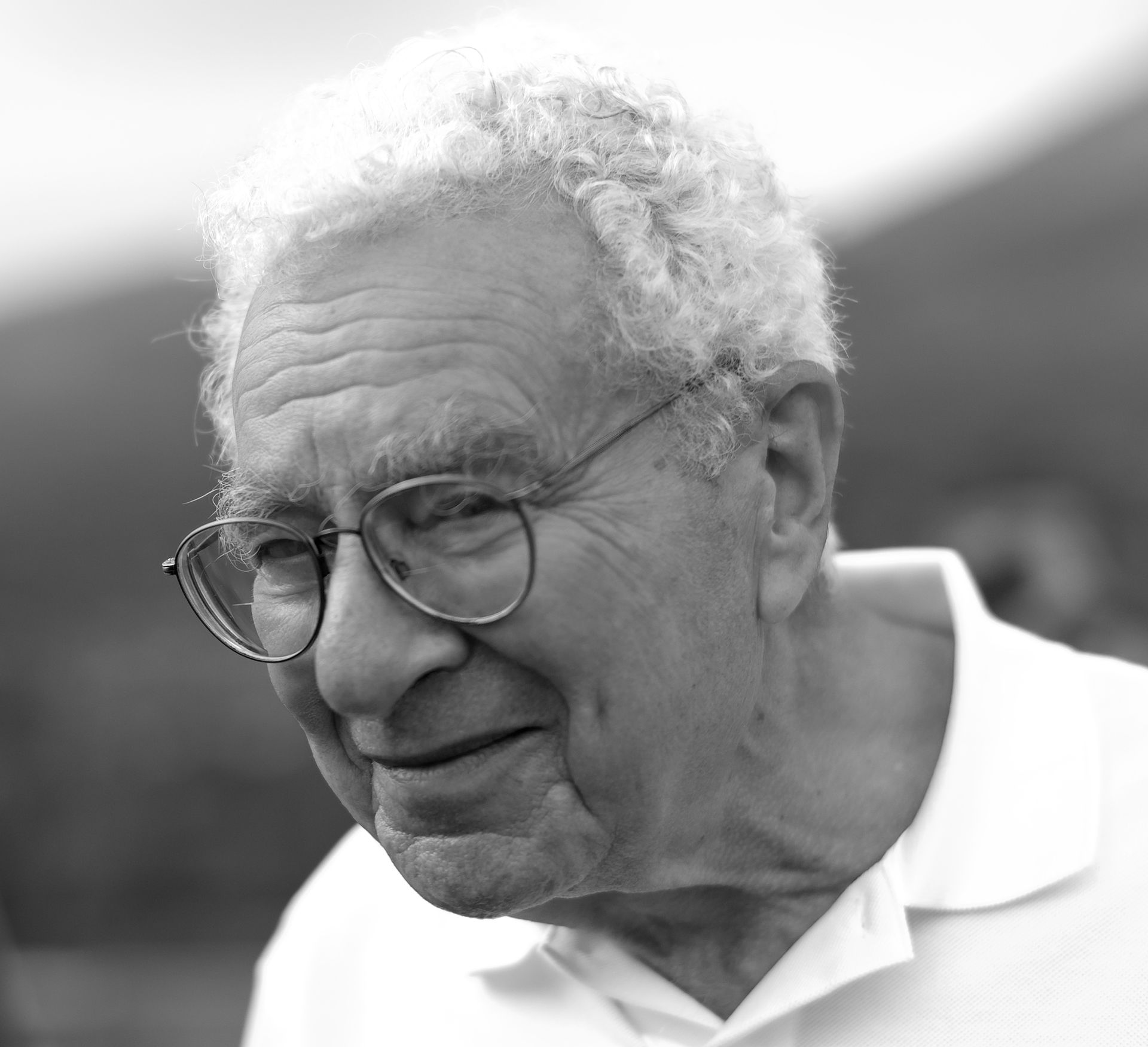

Physicist Murray Gell-Mann was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1969 for his discoveries related to elementary particles—one of which he whimsically named quarks after perusing a rather famous literary work. But in order to understand the origin of quark, it’s important to understand the source of atom and proton as well, and the story that is encoded in the language of physics.

The story of matter begins with two competing ideas. On one side, Aristotle believed that all matter was infinitely divisible—you could cut a chunk of matter in half endlessly, never encountering a piece too small to be further divided.

But some Greek thinkers, like the philosophers Democritus and Leucippus, had another idea. They believed that matter was, as Stephen Hawking later put it in A Brief History of Time, “inherently grainy.” Everything could be broken down into smaller and smaller parts, resulting in a universe composed of tiny, individual particles. In fact, the word atom comes from the Greek word atomos, meaning “indivisible.”

[Just how much did dinos eat for dinner?]

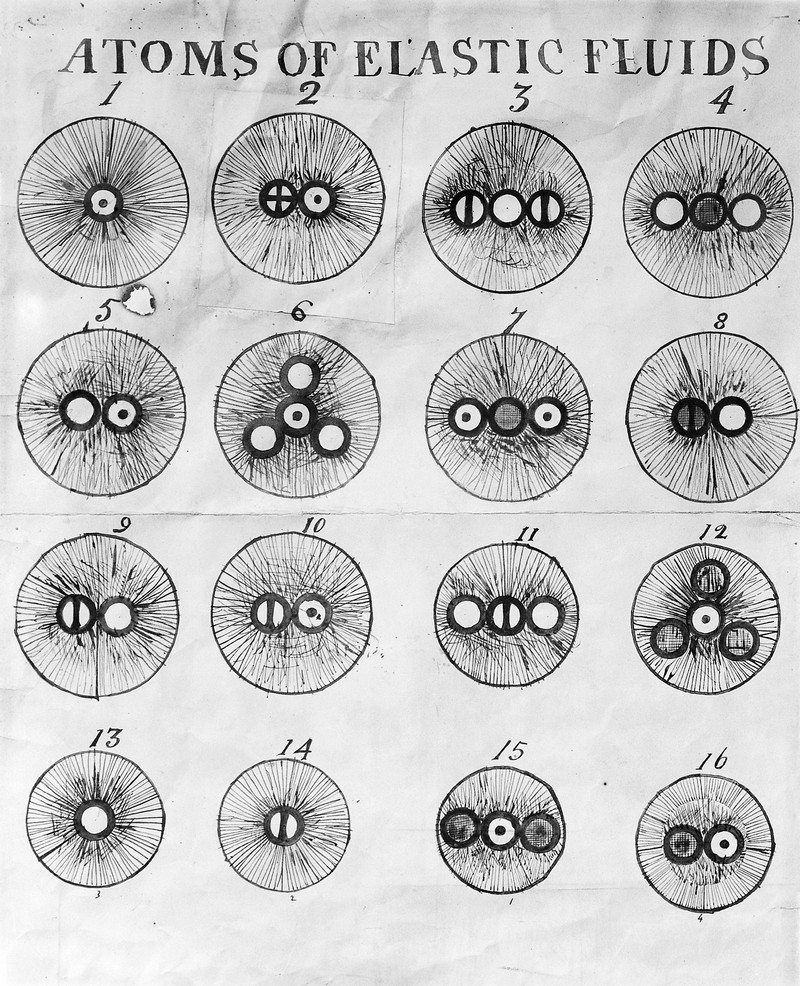

The dispute remained unsettled for centuries, until in 1803 chemist and physicist John Dalton pioneered the development of modern atomic theory. His work laid the foundation for further discoveries and evolution of atomic theory, and in 1911, physicist Ernest Rutherford discovered that atoms do indeed have an internal structure. As Hawking writes, “they are made up of an extremely tiny, positively charged nucleus, around which a number of electrons orbit.”

But what was that nucleus itself made of? At first, scientists thought the nucleus was composed of electrons and a positively charged particle called a proton. The word proton, like atom, has Greek roots. It stems from the word prōtos, meaning “first,” because protons were thought to be the fundamental unit of matter—until about halfway through the 20th century, that is, when a physicist made a teeny, tiny discovery.

[Following a 14,000-year-old breadcrumb trail.]

When Caltech physicist Murray Gell-Mann predicted the existence of an even smaller set of particles in 1964, he playfully dubbed them quarks. There’s a rich tradition of whimsical naming in the world of physics, as is the case with “the God particle,” “flavor,” and “charm.”

But according to Gell-Mann’s book, The Quark and the Jaguar: Adventures in the Simple and the Complex, the tail was wagging the dog. “When I assigned the name “quark” to the fundamental constituents of the nucleon,” he writes, “I had the sound first, without the spelling, which could have been ‘kwork.’”

Luckily, Gell-Mann had a bit of a literary bent: “In one of my occasional perusals of Finnegans Wake, by James Joyce, I came across the word ‘quark.’” The line was:

Three quarks for Muster Mark!

Sure he hasn’t got much of a bark

And sure any he has it’s all beside the mark.

But quark didn’t sound quite like the kwork that was ringing in Gell-Mann’s head. The physicist took a little creative license, and reimagined the line as a call for drinks at the bar:

Three quarts for Muster Mark!

With this adjustment, writes Gell-Mann, pronouncing the word like kwork “would not be totally unjustified.” The reference to the number three was fitting as well, since “the recipe for making a neutron or proton out of quarks is, roughly speaking, ‘Take three quarks.’”

So, should we be saying quark or kwork? The dispute over the nature of matter that began with Aristotle may be settled, but this is one debate that hasn’t yet been put to bed—in a survey, 76 percent of Science Diction readers who voted said they’re sticking with quark, and 24 percent are with Gell-Mann, and say kwork.

Johanna Mayer is a podcast producer and hosted Science Diction from Science Friday. When she’s not working, she’s probably baking a fruit pie. Cherry’s her specialty, but she whips up a mean rhubarb streusel as well.