Following The Burnt Crumbs To The Rise Of Bread

11:13 minutes

Bread is a staple food today. In fact, you can find dozens of varieties at the supermarket—tortillas and pita, naan and focaccia, rye bread and wonder bread and baguettes too. Bread is so ubiquitous that it’s hard to imagine it was once a rare commodity, a labor-intensive specialty that could be made only by husking the seeds of wild grasses, hand-pounding and grinding them, then mixing the resulting flour with water and scorching on a hearth.

[Don’t be a food failure! We’ve got the knead-to-know science behind baking bread.]

Archaeologists working at a 14,000-year-old site in Jordan have now found evidence of an early bakery in the form of burned crumbs, similar to the ones at the bottom of your toaster. After analyzing the crumbs’ structure with a scanning electron microscope, the researchers were able to characterize the crumbs as the charred remains of a flatbread, similar to pita, baked with ingredients like wild einkorn wheat, barley, oats, and the roots of an aquatic plant similar to papyrus. They also determined that the crumbs predate the dawn of agriculture.

Archaeobotanist Amaia Arranz Otaegui wrote up the findings in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, and she joins Ira here to talk about this ancient recipe, and the emergence of bread-like foods before the agricultural age.

[Here’s what we know—and don’t know—about human heredity.]

Amaia Arranz Otaegui is a post-doctoral researcher in archaeobotany at the University of Copenhagen. She’s based in Copenhagen, Denmark.

IRA FLATOW: Our next subject is about bread. Bread is such a staple food today. And every culture has their own.

There’s tortillas, and pita, and nan, and foaccia rye, Wonder Bread baguettes. Bread, it’s so ubiquitous. And it’s hard to imagine it was once a rare commodity, a food for special occasions, maybe.

We could only make it with a lot of hard work, husking, hand pounding, wild grass seeds. Archaeologist working in Jordan have now found the burn sort of toaster crumbs of an ancient batch of bread, a primitive pita that predates even the dawn of agriculture. Here to give us the recipe is Amaia Arranz Otaegui.

He’s a post-doctoral researcher in archaeobotany– I don’t think I’ve ever used that word before– archaeobotany at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark and published a detailed ingredient list of that bread this week in the proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. And she joins us by Skype from Iran. Welcome to Science Friday.

AMAIA ARRANZ OTAEGUI: Hello.

IRA FLATOW: [INAUDIBLE]. Hey. How many crumbs–

AMAIA ARRANZ OTAEGUI: Hey.

IRA FLATOW: –did you find?

AMAIA ARRANZ OTAEGUI: Well, we found more than 600 actually. But we only have analyzed like 24. So we still have a lot of work to do in the future.

IRA FLATOW: Why didn’t anyone see any crumbs before?

AMAIA ARRANZ OTAEGUI: Oh, that’s a good question. Well, because as an archaeologist, I think we have always focused on architecture, pottery, bones, flint, and all these big things, right, that we can’t see with our naked eyes. And small things like seeds and food remains have been long ignored. So I think that this paper will help improve in the visibility of this long ignored remains.

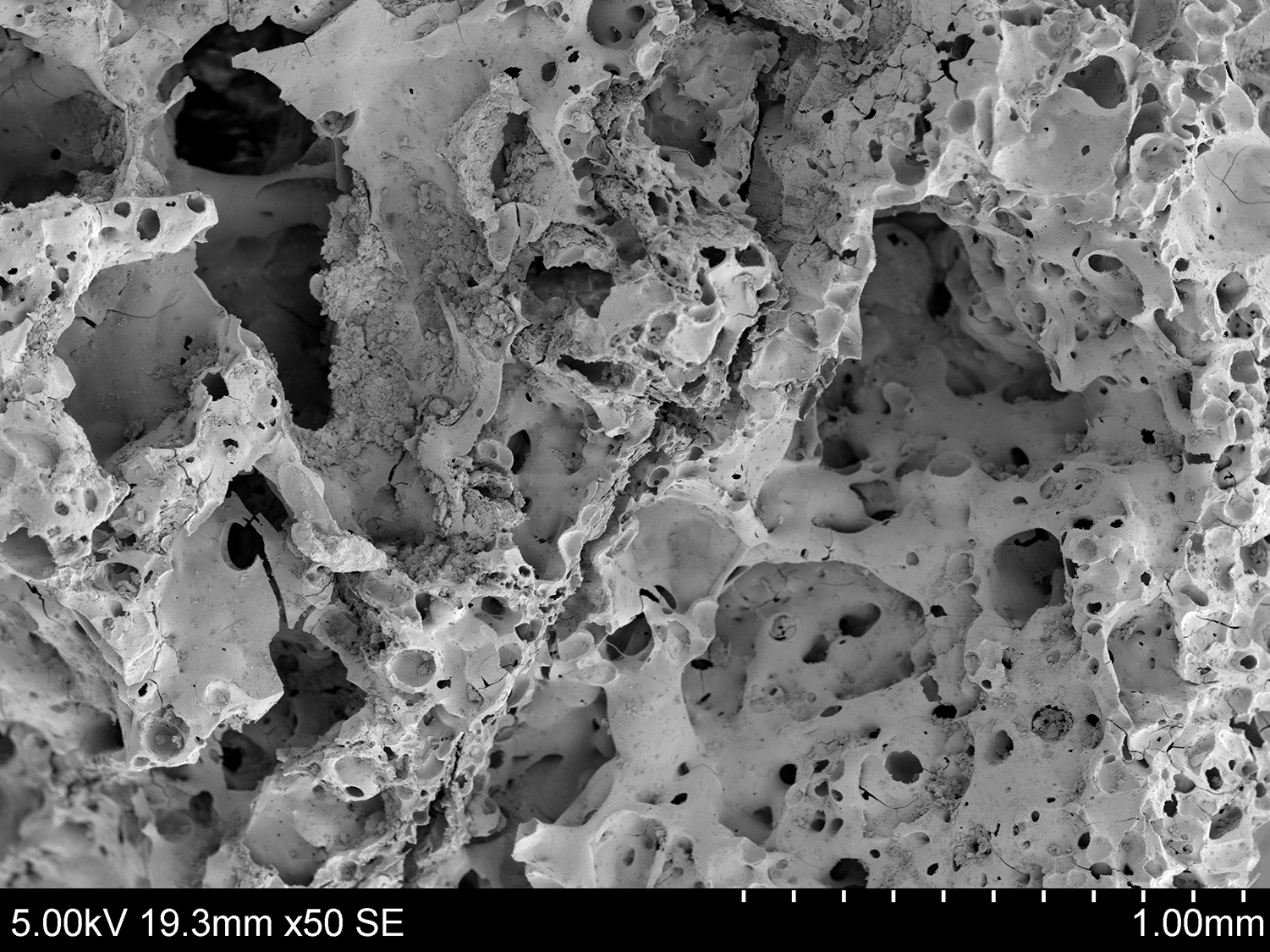

IRA FLATOW: And so once you got hold of the crumbs, you put them under an electron microscope. And we have a photo of that microscopic bread structure on our website at sciencefriday.com/bread. But once you looked at the structure, what did you find?

AMAIA ARRANZ OTAEGUI: So when we look at the structures, when we look at the foot remains under the microscope, we see two things. We see– on the one hand, we see plant particles, plant tissues, microscopic, very small, that inform us on the ingredients of the food. And then we also see the texture, right.

And if you see that image that is on the website, you would see that it’s very porous, right, very, very similar to bread. So these two things are giving us the ingredients in the food product, like the final product. Yeah, to know– yeah–

IRA FLATOW: So give us the recipe. What are the ingredients in this bread?

AMAIA ARRANZ OTAEGUI: Well, it’s not easy actually. It’s a multi-seeded, a multi-ingredient bread I would say. So it has some cereals. We know that these people were using wheat and were using barley and oat, for example. All of them were wild species that we’re growing naturally in the area.

And then they are using something quite interesting, which are tubers, which are the part of the plant that grows under the ground, like a root. So they were using a plant that grows in lakes and it’s an aquatic plant of the family of papyrus. And they were using these tubers to make a flour with them. So I think it’s an exciting thing to see actually because tubers have also been ignored in archeology. So it’s good to see this evidence, actually.

IRA FLATOW: Did it take a lot of work to make this bread?

AMAIA ARRANZ OTAEGUI: Well, for them it must have been a really hard work. First, because they had to find the ingredients, especially cereals. We don’t really know where they were growing at that time. The tubers, this club rush tubers, must have been growing quite close to the site.

But the cereals we don’t really know. So I imagine that they have to find them. They have to walk perhaps tons of kilometers to find them. And then they have to harvest them. And then process them, which is the husking all these wild cereals. It’s a very hard work actually.

The grains are very well protected. It’s not like the wheat we have nowadays that is very easily processed. The grains are really easily released from the plant. But these wild species were really, really well protected.

So it must have been a really hard work for them. And then of course, they had to make the flour. So grind the cereals, grind the tubers, and then make dough and bake it. So it must have been quite some hard work.

IRA FLATOW: I know that we say agri– this is 14,000-year-old bread, and I’m blown away by the fact that there’s still parts of it leftover that haven’t oxidized or there’s– they just haven’t disintegrated. I don’t– is–

AMAIA ARRANZ OTAEGUI: No.

IRA FLATOW: But besides that, we think that agriculture– at least, farming came years and years later after this. So that you’re saying these are hunter gatherers who just would go out and find the wild grains growing, they’re not– I guess I’m asking maybe we should move that timeline back to agriculture? And you’re saying no, they were just wild gatherers.

AMAIA ARRANZ OTAEGUI: Yeah, they were wild gatherers. Yes, that’s something that we know for sure actually. We know that they were not cultivating these cereals at this site. And cultivation comes like let’s say 2,000 or 3,000 years later.

Well, that’s for now, you know. We never know with–

IRA FLATOW: Well, that’s what I’m asking.

AMAIA ARRANZ OTAEGUI: –archaelogy.

IRA FLATOW: Maybe that timeline is wrong. I mean, you’re making a discovery. And maybe some– we’ve heard this numerous times about neanderthals, all kinds of discoveries. We moved the timelines back and forth. I mean–

AMAIA ARRANZ OTAEGUI: Yeah, that’s true.

IRA FLATOW: Which is the evidence, and which is the symptom? So–

AMAIA ARRANZ OTAEGUI: Yeah, the thing with the cereals is that when we look at the seeds, we actually are able to see that they are morphologically wild. So we know that these wild plants were reproducing by themselves. So that’s for sure. And when we look at this site, we also found these wild cereals. So we know that they were not domesticated at all.

So that’s something that we know. But the question is like, why they were doing bread and why they were using these cereals, and why they were taking all this work to do bread. So that’s a big question that we would like to answer in the future.

IRA FLATOW: Why do you question this? I mean, what is there about– is it just so labor intensive you’re saying that you would have to spend so much time making the bread that maybe you should have been hunting something else that might be easier? You’re using up a lot of energy for that calories they’re getting.

AMAIA ARRANZ OTAEGUI: We think so. Yeah, we think so. We think that it must have been easier to– for example the tubers, we know that they were using this tubers that were at hand. They were very close to [INAUDIBLE]. And they are quite easy to process.

So we know that we’re using those. But why were they using the cereals that are really time consuming to process? So there are some researchers that say that products like bread and beer could have been something special, something that you only consume in specific occasions, or ceremonies, or feastings and things like that.

So that’s something that we would like to explore because that’s a possibility. Yeah, I know that there are some authors actually, some from the states like Brian [INAUDIBLE] that suggest this type of hypotheses. So I think they are actually very happy with our evidence to see that bread was made before agriculture.

IRA FLATOW: Because I’m looking at sciencefriday.com/bread. I’m looking at the photos on our web site of what was discovered. And this was a very well laid out oven and processing place there. This wasn’t just something half hazard that they had a rock bowl and a rock. This was not that. This was– so that’s what makes me think that this– they use this more than just occasionally.

AMAIA ARRANZ OTAEGUI: Yeah, actually, I mean, the site itself is quite special. If we look at the fireplaces, yeah, two of them, they are huge. They are like one meter in diameter, very big. And they have tons of food in there.

There were gazelles. There were heirs. There were sheep. There were birds. There were all these tubers of thousands of them, more than 65,000 plant remains that were found. So there was a lot of food in these fireplaces.

And the structure itself is not that large. We tried to fit like 20, not 20, maybe 15 people inside the structure. And we think like OK, this was like too much food for 15 people. So we don’t really know, but it’s an interesting site. And we would like to continue and see what the research tell us.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, right now you have n equals 1 sites. Would you be looking for more sites to figure out, gather more data?

AMAIA ARRANZ OTAEGUI: Yeah, absolutely. I think that’s what we need to do. Actually, in this area where we are working, it’s a black desert. Imagine like a desert, but with a black carpet of stone’s, basalt stones. There is nothing nowadays.

But that’s very good for us because the preservation of the site is incredible. There are many sites around this one. And we are actually digging them.

So we have another site, which is called Shubayqa 6, which also dates to this time period and continues. So it goes into the next 2,000, 3,000 years. So I think this one is going to give us more evidence to confirm our hypothesis.

IRA FLATOW: And the Iranian government is very happy with you working there.

AMAIA ARRANZ OTAEGUI: Well, I don’t know. I don’t know. I haven’t asked them.

[LAUGHTER]

IRA FLATOW: We won’t tell them that you’re there, OK.

AMAIA ARRANZ OTAEGUI: Yeah, all right, you bet. Yeah, you bet.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you very much for taking the time to be with us–

AMAIA ARRANZ OTAEGUI: You’re welcome.

IRA FLATOW: –and staying up so late for us. Amaia Arranz Otegui is a post-doctoral researcher in archaeobotany at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark. BJ Leiderman composed our theme music. If you missed any part of our program, of course you can subscribe to our podcast.

You can also ask any of your smart speakers to play Science Friday. You can hear Science Friday five days, seven days a week. Everyday is Science Friday.

And of course, we’re active on all social media– Facebook, Twitter, Instagram. If you’d like to send us email, you can send email scifri@sciencefriday.com. And we’d be happy to talk to you. Have a great weekend. We’ll see you next week. I’m Ira Flatow in New York.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christopher Intagliata was Science Friday’s senior producer. He once served as a prop in an optical illusion and speaks passable Ira Flatowese.