Grade Level

5-12

minutes

1-2 days

subject

Earth Science

Activity Type:

experimental paleontology, paleontology, lab, observations, Simulation

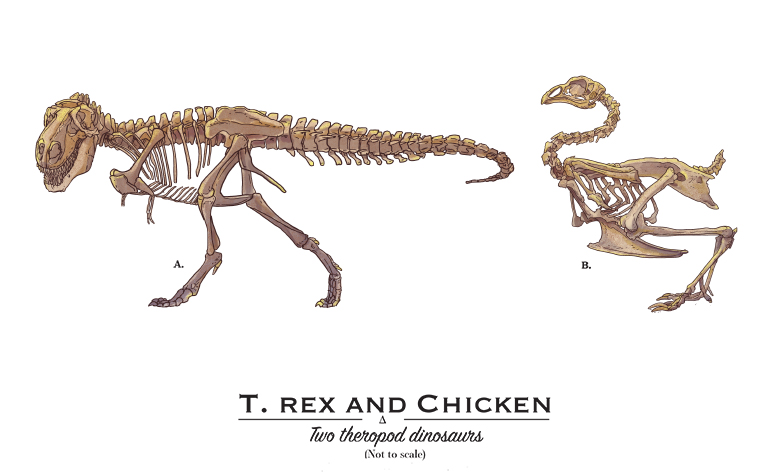

While the fossilized skeletons stick out in images from books or movies in our mind as the primary evidence that dinosaurs and other prehistoric creatures walked the earth, they can’t tell us the whole story of how extinct organisms lived. For that, you need fossilized poop, called coprolites.

“These little magic packages can provide really special perspectives on ancient life,” says Karen Chin, an associate professor of geological sciences at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

“Skeletal fossils don’t always tell you too much about the behavior of animals,” she says. “In addition to diet, [coprolites] can also tell you about what organisms might have been living along with the animal that defecated, and coprolites can also tell you about the conditions under which they were preserved.”

Everyone poops. This adage even applies to prehistoric creatures—from crustaceans to dinosaurs—that lived on land and in the sea. Over the course of any given organism’s lifespan, piles of poop were produced countless times. Unfortunately for those seeking fossilized examples of excrement, poop just doesn’t fossilize as well as bones or shells. Ancient feces fossilized only if a mineralizing agent covered it relatively quickly after it was produced. If mineralization was successful and decomposition was avoided, then feces could fossilize, forming a coprolite.

While it may seem like a less glamorous side of science, the study of petrified poo is incredibly important.

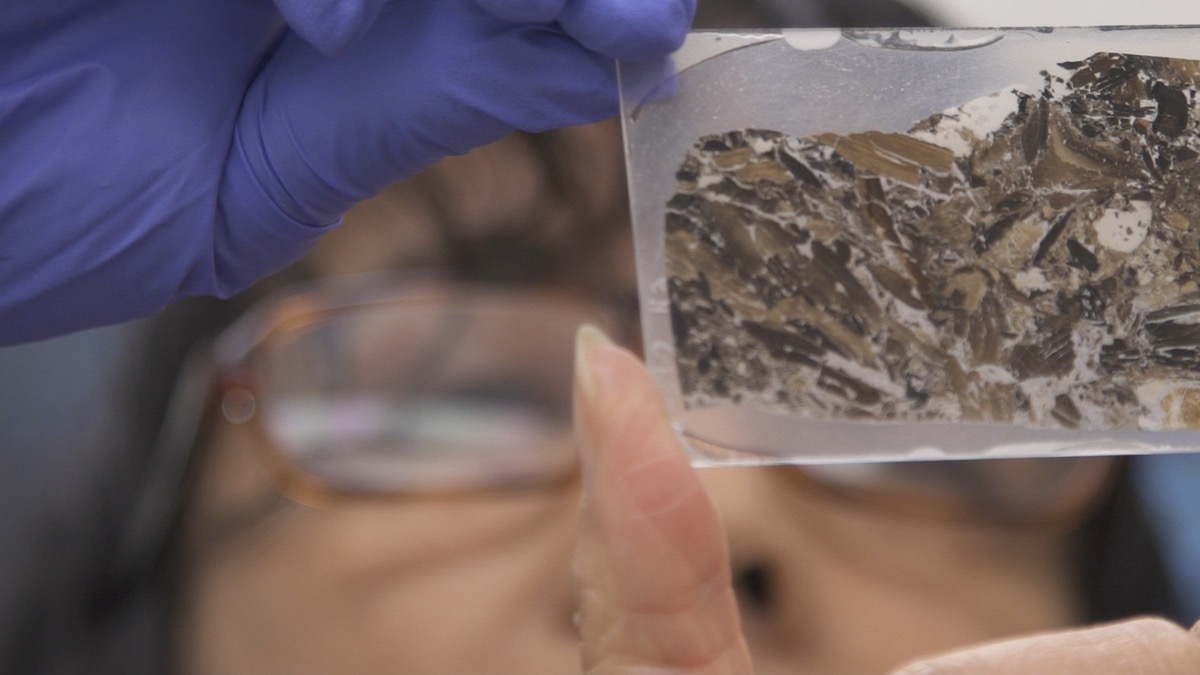

When Chin began studying these coprolites, she found they contained unexpected surprises. Coprolites from herbivorous dinosaurs had more than just leaf matter inside of them. She found dung beetle burrows, snail shells, and tiny pieces of conifer wood. The pieces of conifer wood were no ordinary pieces of wood—they had actually been rotting before being ingested. This is incredibly intriguing as rotting wood isn’t on the diet of many organisms, even herbivores such as these dinosaurs.

In Choteau Mountain’s Two Medicine Formation in Montana and the Kaiparowits Formation in Utah, fossil body parts, coprolites, and trace fossils, which are fossilized indicators of an organism’s presence, can be found. These two formations contain fossils dating back to the late Cretaceous period, which is the period just before dinosaurs went extinct. Famous dinosaurs such as triceratops and Tyrannosaurus rex roamed the area, and fossils of these species along with many other creatures, are found in the Two Medicine and Kaiparowits Formations.

For this activity, you’ll step into the shoes of Karen Chin to see what you’re able to gather from coprolite samples from the Two Medicine and Kaiparowits Formations. You’ll try to answer the same question Dr. Chin pondered: Why is there wood in the fossilized poop created by herbivorous dinosaurs?

Discovering The Past Through Dino Poop

Analyze Your Own Dino Poop Treasures

Materials Per Pair Of Students

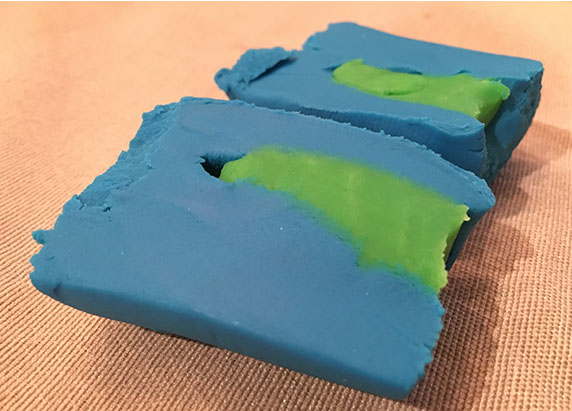

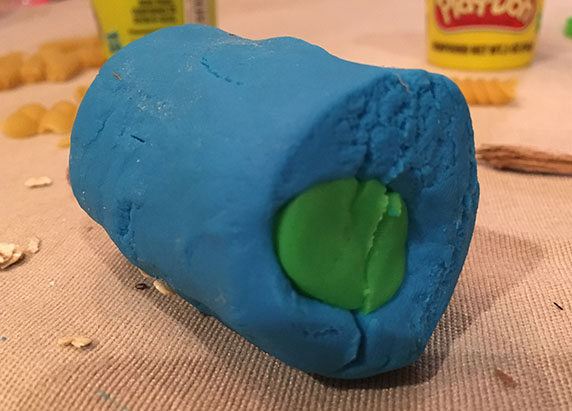

- Small containers of children’s modeling clay like Play-Doh or a Play-Doh-like substance. Be sure to have at least three different colors. One color for coprolites from each formation and one to represent fossilized dung beetle tunnels

- Small shell noodles to represent snail shells

- Pieces of bark, softer wood that may be beginning to decompose is even better than mulch

- Oatmeal to represent remnants of invertebrates

- Pieces of tri-colored Rotini noodles to represent remnants of fungi

- Plastic knife

- Wax paper

- A set of student handouts (digital or printable PDF)

Teacher Preparation Notes

- Use the following Teacher’s guide to create your coprolites.

- Do NOT show the students the Science Friday video before the activity.

- Create coprolites before the activity begins. Give yourself 2-3 days for the material to dry out and harden enough to be useful for the activity.

- Be sure to keep track of your color code for the Two Medicine Formation in Choteau Montana and Utah’s Kaiparowits Formation.

Teacher Directions

- Arrange students into groups of 2-4. Provide half of the group with coprolites from the Two Medicine Formation and the other half with coprolites from the Kaiparowits Formation. Each student should be provided with a plastic knife, a portion of wax-paper upon which to place their coprolite and conduct their investigation, and a student guide (there is a separate student guide for the Kaiparowits and Two Medicine Formations).

- Tell your students they have been asked to join a scientific team studying coprolites, or fossilized feces, to learn more about the daily habits and diets of dinosaurs from the late Cretaceous. Their job will be to study coprolites for fossil clues about eating habits of dinosaurs from that time in addition to figuring out why pieces of rotting wood are found in the coprolites of herbivorous dinosaurs in these two formations.

- Provide students 5 minutes to observe and record the surface features of their coprolites and record them in their student guide.

- Show students how to create a cross-section of a coprolite using the plastic knife on top of the wax paper, and one of the coprolites you prepared earlier. To create a cross-section simply cut a thin slice, no thicker than 1 centimeter, from your coprolite in whichever direction is easiest or most convenient. If there are any pieces that are too big or can’t be cut within the cross-section tell the students they can remove these sections from the coprolite and observe them with the cross-section.

- Provide students 15 minutes to cut cross-sections of their coprolite as well as sketch and record their findings, there are 3 sections provided in this activity for them to do so. If your students create more than 3 cross-sections, encourage them to create their own extension of the handout on a separate piece of paper to continue recording their data.

- Provide 20 minutes for students to work by themselves or with another student who investigated a coprolite from the same formation to create a hypothesis about the origin of the material they found inside their coprolite, and another hypothesis as to why pieces of rotting wood have been found in the coprolites of herbivorous dinosaurs. Students should do so based on their findings from their own coprolite.

- Provide 10 minutes for students to share their findings with students who investigated the coprolite(s) from the other formation. Focus on sharing the characteristics of the coprolites from both formations and the reasoning why rotting wood is found in coprolites from herbivorous dinosaurs.

Student Directions

Follow the coprolite dissection procedure to create cross-sections of your coprolite, then sketch and describe your coprolite cross-sections. Label any important pieces or materials that you find within the fossilized feces. You should repeat this process several times to get the complete picture of what the eating habits of the dinosaur that created this coprolite were.

By yourself, or with a partner who investigated coprolites from the same formation, create a summary of what you found within your coprolite. Be sure to cite specifics such as what exactly you found, how much of it, and where. After completing your summary use the time allowed by your teacher to explain why pieces of rotting wood could be found in coprolites of herbivorous dinosaurs from your formation using your findings

Share your findings and hypothesis with your group who were studying coprolites from the other formation. After sharing your findings with each other, create a group conclusion about the habits of these dinosaurs and a hypothesis as to why these herbivorous dinosaurs regularly had rotting wood in their feces. How do the findings from the other formation support or conflict with your original hypothesis? Be sure to provide specific examples from the exploration of the coprolites from both formations to support your claim.

What The Scientists Found

Based on her conclusions, Karen Chin concluded that dinosaurs didn’t purposefully eat conifer or pine tree wood. The presence of wood that was rotting was confusing to scientists as it generally isn’t believed that herbivorous dinosaurs ate wood as part of their diet. Through extensive testing, however, it was determined that the wood that was being found was rotting before it was eaten by dinosaurs. Chin hypothesized that the wood being consumed was being consumed on accident by the dinosaurs that were eating it. She postulated that the dinosaurs were ingesting the wood as they were trying to eat the insects that were living in or on the rotting wood meaning the dinosaurs were actually omnivores instead of herbivores. Scientists researching in the Kaiparowits Formation supported her hypothesis when they found fossilized remnants of the same insects and other organisms in the coprolites of herbivorous dinosaurs as well.

Reflection Questions

- Coprolites helped support an important discovery about herbivorous species. What could be discovered about carnivorous dinosaurs using their coprolites?

- What do you think coprolites from dinosaurs that live off of scavenging such as vultures today could reveal about how those organisms lived?

20 years from now, while working in your paleontology lab investigating the coprolites of carnivorous dinosaurs you notice they contain a significant amount of plant material. Make a hypothesis about how this plant matter ended up in the feces of a carnivorous dinosaur?

Check Out More Dino Resources!

How Do Scientists Know What Dinosaurs Looked Like?

Put yourselves in the shoes of a paleontologist and paleoartist as you try to recreate what dinosaurs looked like using the same methods as the experts.

How Did Dinosaurs Walk?

Fossilize Me! Card Game

Explore the diversity of fossil types and test your knowledge with the Fossilize Me! Card Game.

NGSS Standards

3-LS4-1 Biological Evolution: Unity and Diversity

Analyze and interpret data from fossils to provide evidence of the organisms and the environments in which they lived long ago.

MS-LS4-2 Biological Evolution: Unity and Diversity

Apply scientific ideas to construct an explanation for the anatomical similarities and differences among modern organisms and between modern and fossil organisms to infer evolutionary relationships.

Credits

Educational Resource: Brian Soash

Video: Luke Groskin

Editing: Ariel Zych and Lauren Young

Digital Producing: Lauren Young and Brian Soash

Educator's Toolbox

Meet the Writer

About Brian Soash

@BSoashBrian Soash was Science Friday’s educator community leader. He worked to connect educators, schools, and districts with the outstanding educational content being developed by Science Friday.