How Will AI Image Generators Affect Artists?

16:32 minutes

Listen to this story and more on Science Friday’s podcast.

Back in August, controversy erupted around the winning submission of the Colorado State Fair’s art content. The winning painting wasn’t made by a human, but by an artificial intelligence app called Midjourney, which takes text prompts and turns them into striking imagery, with the help of a neural network and an enormous database of images.

Back in August, controversy erupted around the winning submission of the Colorado State Fair’s art content. The winning painting wasn’t made by a human, but by an artificial intelligence app called Midjourney, which takes text prompts and turns them into striking imagery, with the help of a neural network and an enormous database of images.

AI-based text-to-image generators have been around for years, but their outputs were rudimentary and rough. The State Fair work showed this technology had taken a giant leap forward in its sophistication. Realistic, near-instant image generation was suddenly here—and reactions were just as potent as their creations.

Tech enthusiasts lauded the achievement, while artists were largely concerned and critical. If anyone could make a painting in just a few seconds, why would someone need to commission an artist to produce an illustration, or even bother spending years learning art at all?

The other major issue that artists pointed out was that the databases of these image generators—DALL-E 2, Midjourney, Stable Diffusion—are largely built off existing images from artists. The companies behind these programs scraped billions of images from the web, including the hard work of artists, both dead and alive. But because of fair use precedent, which these models likely fall under, and the nebulous process of how these programs select specific images, it’s difficult for artists to make a legal case against generative AI developers.

This has left some artists to fear the worst: Will these algorithms, which wouldn’t be able to produce its images without their work, one day replace them?

As generative AI continues its reach beyond visual art, what do advances of this technology mean for the rest of society? In what ways could this software affect vulnerable communities? To help us decode the wild world of AI image generation is Tina Tallon, assistant professor of AI and the Arts at the University of Florida, Genel Jumalon, an illustrator and VFX artist, and Stephanie Dinkins, a transmedia artist who’s incorporated AI into her work for the past decade.

To get a better grasp of AI image generation, we thought it made sense to directly interact with it for this segment, and have it play some role in the editorial art. But due to ethical concerns raised by artists about the contents of these models’ databases, we didn’t want to use a direct result from one of them as the art.

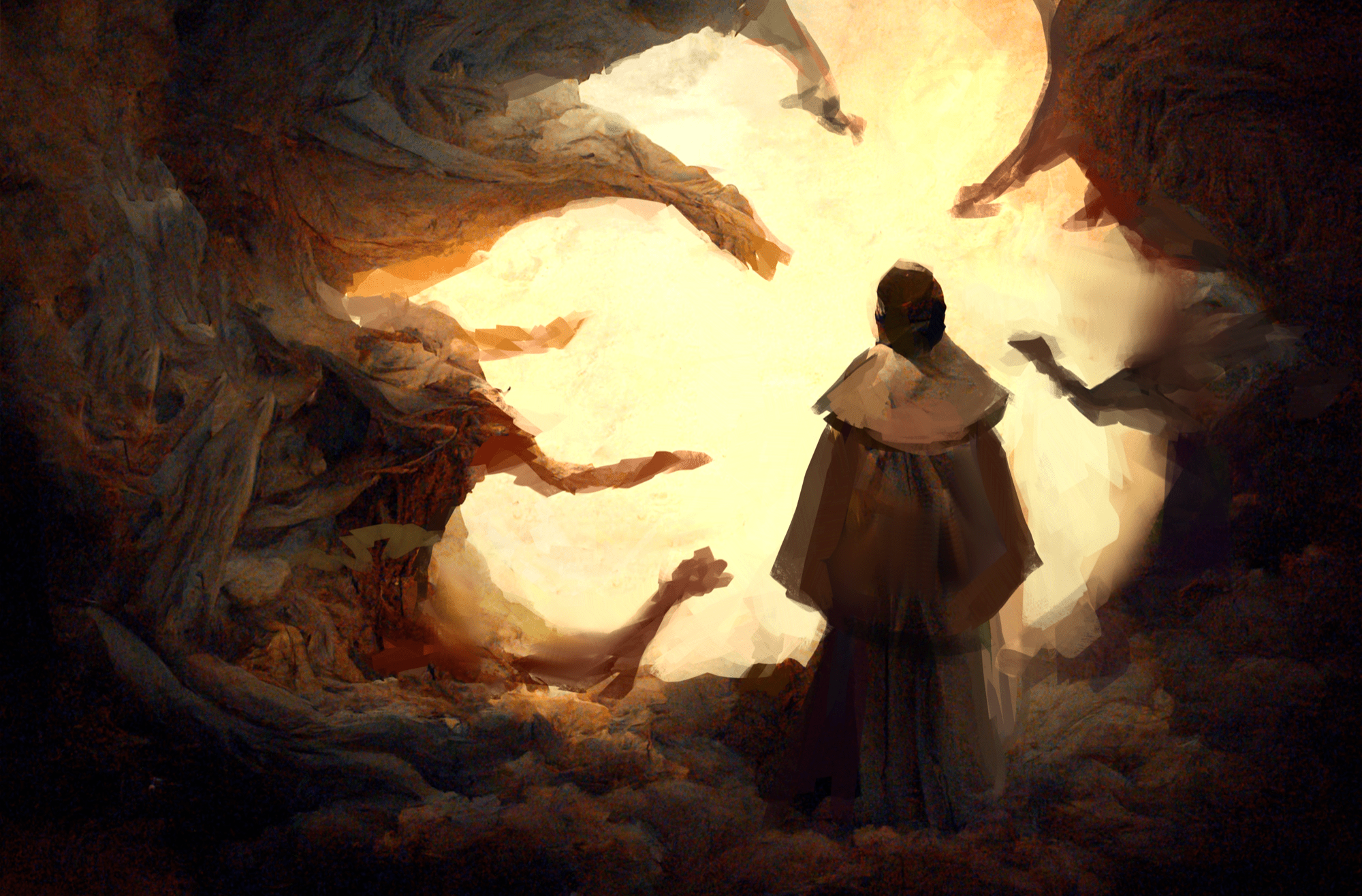

So, we partnered with the illustrator Genel Jumalon, who sometimes uses Midjourney to generate ideas for their paintings. After they give Midjourney a text prompt, and it spits out some images, Jumalon chose their favorites and completed the illustration by hand. This is the process we used for the above art.

Even though the final illustration is original, Jumalon still wanted to keep as much potentially copyrighted material as possible out of the initial image generations. In addition to the main subject prompt text, they usually add the name of a long-dead illustrator whose work is in the public domain. In this case, it was Jean-Léon Gérôme, a 19th-century French artist who has inspired Jumalon’s style.

Producer D Peterschmidt left the subject of the prompt up to Jumalon, asking only that the final illustration reflected how Jumalon felt about the emergence and impact of AI on the art world. The text prompt Jumalon provided Midjourney was “the creation of Adam in the style of Jean-Léon Gérôme,” which returned the below 36 images. If Jumalon was particularly inspired by one of the results, they lightly sketched over them.

From there, D selected three favorites and Jumalon took to Photoshop to digitally paint and expand on those concepts, which resulted in these drafts.

Finally, Genel combined some favorite elements from all three for the final illustration below, along with a time lapse of the final leg of the process.

Exploring what AI image generation means has long been a part of transmedia artist Stephanie Dinkins’ work. Since 2014, she has been incorporating AI into her work, after encountering—and later conducting a series of interviews with—Bina48, a humanoid robot with the appearance of a Black woman, whose AI brains were built from a series of interviews with the wife of the funder of the project.

In 2018, she made her own chatbot, in an artistic project titled Not The Only One. She placed the interactive AI into the shape of a vase, drawing from a database of oral histories Dinkins collected from three generations of her family as they reflected on the Black American experience. While its responses may not always be comprehensible, Stephanie’s project illustrates the limits, but also the joys of AI constructed from a personal dataset.

Don’t worry, it’s right here.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Tina Tallon is an Assistant Professor of AI and the Arts in the University of Florida’s College of the Arts, where she is director of the Florida Electroacoustic Music Studio and affiliate faculty in the UF Informatics Institute.

Genel Jumalon is an illustrator and visual effects artist at Skydance Interactive.

Stephanie Dinkins is a transmedia artist and teaches at Stony Brook University.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

Back in August, there was a bit more controversy surrounding the Colorado State Art Fair Contest than usual. And it was centered around the winning painting. It was painted not by a person who submitted it but by an artificial intelligence app called Midjourney, which turns a short amount of text into striking images thanks to machine learning and an enormous database of pictures. Many artists online were furious. They were saying that the piece shouldn’t have been allowed to be entered. Others wondered if it meant the beginning of the end of their careers.

There’s a lot to talk about here. And joining me to delve deeply into the world of AI-generated art is SciFri producer D Peterschmidt. Hi, D.

D PETERSCHMIDT: Hey, Ira. Yeah. Have you seen other AI art from some of these platforms, DALL-E, Midjourney, Stable Diffusion?

IRA FLATOW: Well, no, I can’t say that I have.

D PETERSCHMIDT: Yeah. It’s pretty wild and a little disturbing. It definitely provokes some mixed emotions. All you really do is you type in some words into a text field, like “Ira Flatow in the style of Salvador Dali,” and it gives you a handful of images. Some of them are kind of messy. They’re obviously fake looking. But more often than not, it can actually give you some pretty realistic results. And also this guy who won the contest, Jason Allen, he gave this really punchy statement afterwards. And he said, art is dead. It’s over. AI won. Humans lost.

IRA FLATOW: Oh, really? That’s a pretty heavy statement. I mean, writing off all of humanity.

D PETERSCHMIDT: Yeah, no big deal. And I basically wanted to know, is art really dead? Is AI going to kill it? And the first person I talked to was Tina Tallon. And she’s an assistant professor of AI and the Arts at the University of Florida.

Do you remember the last thing you typed in to DALL-E?

TINA TALLON: To be honest, I think it was something related to Aperol spritzes.

[LAUGHTER]

D PETERSCHMIDT: Why?

TINA TALLON: I was trying to create art to go above my bar cart. And I couldn’t find an Aperol spritz poster that I liked on Etsy.

D PETERSCHMIDT: When she’s not putting together her dream bar cart, Tina teaches her students about AI systems, how to code with them and how to use them ethically.

TINA TALLON: Many decisions that we’re affected by are made by artificially intelligent agents, whether we know it or not. And so it’s something that deserves a lot of conversation beyond its applicability to the arts. It’s something that’s becoming increasingly more common in society.

A lot of these tools have really proliferated over the past two months. So we’re kind of on the bleeding edge in terms of seeing how it’s all going to shake out and how these things are going to disrupt not only the creative industry but also society in general when it becomes so much easier to generate really high-quality images of literally anything. Is that a good thing? I don’t know. That remains to be seen.

D PETERSCHMIDT: If you had to abstract DALL-E’s process of what it’s doing to something a human would actually do, how would you put that?

TINA TALLON: So not unlike the processes by which humans learn how to create art, DALL-E is examining a ton of different artworks. So for instance, in many fine arts programs, students learn by copying works of art in the canon. And I think because, again, in AI we’re trying to replicate human mental cognitive processes, these tools are trying to learn how to create art.

D PETERSCHMIDT: To replicate the way a human’s brain works, you need a couple of things. First is a neural network.

TINA TALLON: So similar to neural pathways in the human brain, if we’re trying to form a good habit, you want to strengthen the neural connections that result in that good habit. And if you want to break a bad habit, you want to disincentivize the neural connections. And so the same thing happens in neural networks, where we’re trying to figure out which of those we want to prioritize.

D PETERSCHMIDT: And the second thing are data sets, lots of data sets.

TINA TALLON: With DALL-E, you have to train it on an enormous number of images in a variety of different styles. However, one of these models can analyze more art than we will ever be able to in our lifetime. And so in terms of scale in that respect, the learning process is very different.

D PETERSCHMIDT: To make these models, OpenAI and others downloaded hundreds of millions of images from the web. And because one of DALL-E’s main goals is to basically be an art generator, a lot of those images came from artists, dead and alive. As far as the legality of all this?

TINA TALLON: Right now it’s not a violation of copyright. It seems like you should say yes, people obviously own their artwork. Legally, though, the way in which that artwork can be used is still up for debate.

D PETERSCHMIDT: So it looks like these AI-generated images fall under what’s called fair use, which is a law that has protected works of people like Weird Al. If you make something using someone else’s copyrighted material but you transform it in a way that makes it unrecognizable or a different thing entirely, you are protected by fair use. There’s a lot of gray area here. But at the moment, the law favors AI image generators and not artists.

TINA TALLON: Recent US court cases have held that it’s not a violation of copyright for your data to be used to train an AI model. That might change.

D PETERSCHMIDT: Can you talk about your personal feelings on the ethics of acquiring a data set? Like, obviously, data sets are not unethical to have fundamentally, but–

TINA TALLON: Right. They can be ethically constructed, though. Some data sets are more ethically constructed than others. Data are a reflection of a society’s values. And I’m a huge proponent of consent in all possible realms, but especially when it comes to data set creation.

D PETERSCHMIDT: A lot of the popular image generation models, DALL-E, Midjourney, Stable Diffusion, their developers did not get permission from artists to scrape their work to make these models, models that ultimately may undermine those artists’ ability to get work in the future.

TINA TALLON: I think that they should have some say into whether or not they want their work incorporated into these data sets.

GENEL JUMALON: It’s not even difficult to even imagine an ethical AI.

D PETERSCHMIDT: Genel Jumalon is an Illustrator and VFX artist.

GENEL JUMALON: And it’s this. It’s just like, hey, just don’t use copyright data. And if people want to contribute to this data set, they can. And here’s the crazy part. Artists are weird. We like weird things. We like new and interesting things. And I’d be willing to put my artwork in those data sets because I like weird things and I like trying to see where things are. But the fact that these companies didn’t ask any of us for our consent is really telling to the ethics of how they’re producing it. And it’s just frustrating.

D PETERSCHMIDT: Even though Genel is not a fan of how these companies establish themselves, they’re actually pretty pumped about this basic idea. So much so that they’ve begun to integrate it into their illustration process.

GENEL JUMALON: I thought it was cool and rad as heck.

[LAUGHTER]

I was like, whoa, this is very wild, right? This is practically like an acid trip, honestly. But there’s the ethics issue that comes with it after the initial wow. I was like, oh, no. This could easily be used for some very unethical practices, and it has been.

D PETERSCHMIDT: And to avoid some of those ethical minefields, Genel has only been using Midjourney for the concept stage of their paintings.

GENEL JUMALON: You know when you look at clouds and you can pull shapes for things. Like, oh, that’s kind of like a tiger or like a dog or something like that. That’s kind of how my brain works. What’s exciting for me is it’s able to tap into things, that’s it’s like I’m able to play with compositions that I would never come to conclusion with, and then be able to infuse my own aesthetics and ideas about where this composition should go towards.

For me as an artist, it’s more about trying to make it as much of my artwork as possible.

D PETERSCHMIDT: Genel is echoing an idea I saw on Twitter, that maybe a more ethical use of the software is to use it as a jumping-off point. Generate a bunch of quick visual concepts, get inspired, and then complete the illustration just like a good old-fashioned human would. That way the stolen art side of this stays out of the final product, and maybe the artist will have more time to make the illustration better.

So I thought it would be interesting to commission Genel to make editorial art for this segment based on that process, which they’re already familiar with. Usually when I contract artists for editorial art, I have a pretty good idea of what I want the final illustration to look like. But I wanted to give Genel and Midjourney a prompt and let them take it from there.

So yeah, the general prompt I want to give you is how you feel as a working artist about the expansion of AI on the art world. And I’m just going to leave it like really vague like that.

GENEL JUMALON: Very artsy, yes.

D PETERSCHMIDT: I know, yeah. So yeah, how are you feeling about this project right now?

GENEL JUMALON: I am excited. Like I said, I’ve just been very vocal on Twitter about trying to find this middle ground solution. Because it’s usually like the opposite corners, where it’s like AI should never be used and also AI is going to replace all artists. I understand the sentiments of a lot of artists being threatened about that. And a lot of my energy, at least with my own platform, is less about trying to stop or impede it and trying more about to protect the artists.

We need to find ways to coexist in this weird world that we’re living in right now.

IRA FLATOW: So they want to find a middle ground someplace, it sounds like.

D PETERSCHMIDT: Yeah. So they’re going to come up with a prompt. They’re going to put it in Midjourney. And Midjourney is going to give them back a bunch of results. We’ll decide on our favorites. And they’ll paint it from there.

IRA FLATOW: It sounds great.

D PETERSCHMIDT: Yep. And I wanted to dig in more to this idea Genel brought up, that we should maybe start thinking of ways to live with this technology since it doesn’t really seem like it’s going anywhere. And some artists are also concerned about how generative AI will affect vulnerable communities.

STEPHANIE DINKINS: My name is Stephanie Dinkins. I am an artist who works with artificial intelligence and emerging technologies. I think my art is really a set of experiments trying to figure out where communities of color fit into the technological future.

D PETERSCHMIDT: I got in touch with Stephanie because she has spent almost the past decade integrating AI into her art, and using it as a way to reflect on race and gender. She’s made an AI chatbot, called Not The Only One, that you can have conversations with.

To construct its database, she collected oral histories from three generations of her family, where they reflected on the Black American experience.

A lot of artists over the past few months online have been very vocal about, like, I’m never going to touch this. I’m never going to use this in my work. But what do you say to people who, for their very own legitimate reasons, refuse to engage with these systems?

STEPHANIE DINKINS: So in the realm of artists, I’m like, OK, that’s your prerogative. Go ahead. In the realm of people, I always think that we do not have the luxury and cannot afford not to engage this technology.

I don’t like this idea of having to play catch-up once we realize how deeply embedded the technologies are in the world that we’re living in and how the ability to craft some of it, work with it, understand it, gives you a power, or at least the avenue to power. And so for me, I much prefer that people engage and try to figure out than abstaining.

D PETERSCHMIDT: Even though the developers of these models are not transparent with how their algorithms work, Stephanie has been trying to get a peek behind the curtain anyway. Since 2016, she’s been typing in different variations of the words “Black woman” into these models, and seeing what kind of images they give back to her. And what they returned at first was not what she was expecting.

STEPHANIE DINKINS: And what came back at me was a kind of image of a white figure in a black cloak, right? And you have to think– I’m like, what? Why am I getting this result? How is this functioning?

D PETERSCHMIDT: But those results have changed lately.

STEPHANIE DINKINS: I’ve been running a few DALL-E 2 examples, and it’s phenomenal what it can come up with now. Like just the other day, I ran– what was it– a Black woman laughing in a field of roses. And I got images of a Black woman laughing in a field of roses. And not only a Black woman, but a dark-skinned Black woman. Which to me was also something interesting, right?

And if you look it up on the OpenAI web page, they explain how they’re trying to be more inclusive. They explained how they’re trying to keep offensive information out of the data set. And then I was thinking a lot about that. It’s like, well, what does that mean, and how do we go there? Like, is my job done? I don’t need to think about this. Or is it that now I think we need to even be more vigilant in certain ways, right? Because the systems are going to be putting out things that feel really acceptable in certain ways. And then the question becomes about where real cultural attune-ness comes into play.

D PETERSCHMIDT: Despite instances like this, where OpenAI is trying to appear more equitable, Tina Tallon doesn’t think we should leave it up to these powerful tools to make the right decisions.

TINA TALLON: We need to have some sort of governing body that’s able to audit these tools and examine what their impacts might be. Similar to how we have an FDA that looks at new medical interventions and what their impact on society may be, I think we need the same thing for algorithms. What we’ve seen time and time again is that the restrictions come too late. And we need to put the brakes on a lot of these things if we want to really make sure that we’re forging the best future possible that involves both humans and AI.

D PETERSCHMIDT: Hey, Genel.

A week later, I got back on the phone with Genel to check in on those first drafts, which were generated by Midjourney.

GENEL JUMALON: Cool, cool, cool, cool. Let me send some stuff your way. I thought it’d be really interesting to do a very modern interpretation of The Creation of Adam.

D PETERSCHMIDT: Genel wanted to keep out as much potentially copyrighted material as they could, so they typed in, quote, The Creation of Adam, in the style of Jean Leon Gerome. Gerome was a 19th century artist, whose work has inspired Genel’s art. He’s obviously long dead, which should put his art in the public domain.

OK, cool. I’m looking at this now. This is pretty wild. Hold on.

You can check out what all this looks like at sciencefriday.com/aiart.

Genel sent me 36 thumbnails arranged on a 6-by-6 grid. They were all variations on the same basic idea, ominous swirling clouds, disembodied outstretched hands, mysterious cloaked figures. They were like religious paintings from my nightmares.

The more I’m looking at this, the more I’m freaking myself out. It’s like I’m starting to see skulls in there and twisted faces.

GENEL JUMALON: That’s the fun part for me. It’s like, what are these shapes? Is that a dragon? It’s weird. Because the idea of creating prompts from artists that have passed away, you’re creating artwork that they would have never made in a weird, almost sci-fi, necromancy kind of thing, right? And now you have art that never existed from this artist. And it’s almost like looking at parallel timelines of things that never happened.

D PETERSCHMIDT: Yeah. Yeah. Maybe this is the most sci-fi thing about it to me so far, I think actually directly interacting with it in this way, where you are peering into alternate timelines that you can just create at will. And it’s like it’s here right in front of me. I’m looking at it. It’s kind of surreal.

GENEL JUMALON: Picasso making the Mona Lisa. That’s a thing. You can literally write in the art thing, and it’s a thing we can see now. And it’s so wild. Like, there’s a timeline that that happened, and it’s just–

D PETERSCHMIDT: Yeah, exactly.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. That’s a really interesting idea, having artists paint like other artists.

D PETERSCHMIDT: Yeah. And my big takeaway is that, at the moment at least, it seems like these AI applications, they’re more of an assistant, just to help take care of some busy work, and then we can focus on the creative stuff. But I think, for visual artists like Genel, the threat is definitely bigger.

But anyway, we have a ton of stuff for listeners to check out on the website. We have Genel’s final human-painted illustration, all the works in progress of it. They even took screen recordings during the painting process. And we also have samples of Stephanie Dinkins’ own AI-influenced artwork on that page, too. All that’s on our website, at sciencefriday.com/aiart.

Thank you, Ira.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/.

Dee Peterschmidt is a producer, host of the podcast Universe of Art, and composes music for Science Friday’s podcasts. Their D&D character is a clumsy bard named Chip Chap Chopman.