Subscribe to Science Friday

Researchers recently used near-infrared photography to get a detailed look at ancient artwork showing scenes of wild animals tangled in a fight. But these weren’t paintings on a cave wall. They were tattoos on the arms of a Siberian woman who lived 2,300 years ago. What can ancient ink tell us about our ancestors?

Sticking and poking their way into this with Host Flora Lichtman are archaeologist Aaron Deter-Wolf and his research collaborator, tattoo artist Danny Riday.

Further Reading

- Read more about ancient tattooing techniques discovered in this study via Live Science.

Sign Up For The Week In Science Newsletter

Keep up with the week’s essential science news headlines, plus stories that offer extra joy and awe.

Segment Guests

Aaron Deter-Wolf is an archaeologist for the Tennessee Division of Archaeology in Nashville, Tennessee.

Danny Riday is a tattoo artist and independent researcher based in Les Eyzies, France.

Segment Transcript

FLORA LICHTMAN: Hey, I’m Flora Lichtman, and you’re listening to Science Friday.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Today on the show, archaeologists are turning their attention to an art form that’s been largely overlooked– tattoos.

DANNY RIDAY: To modify is human. And it has been since the beginning.

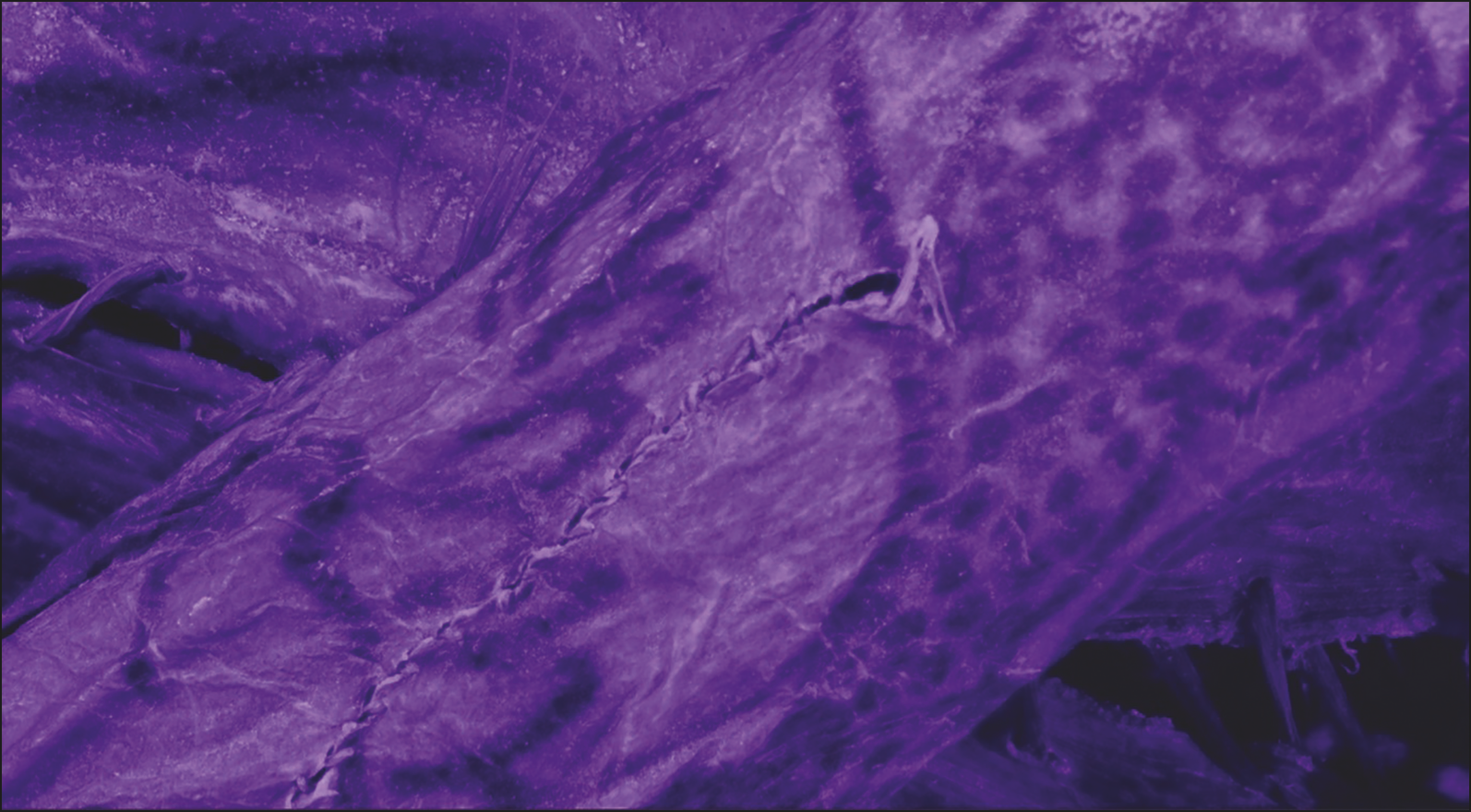

FLORA LICHTMAN: Last month, researchers used near-infrared photography to get a brand new, detailed look at human art from thousands of years ago, a beautiful scene of wild animals kind of tussled in a fight. But these weren’t paintings on a cave wall or a rock somewhere. They were tattoos on the arm of an ancient Siberian woman who lived 2,300 years ago.

Ancient tattoos may seem like an unconventional academic focus, which is why I love the story so much. So what can ancient ink tell us about our ancestors? A lot, according to my next guests. Here to stick and poke our way into this topic are Aaron Deter-Wolf, archaeologist for the Tennessee Division of Archaeology based in Nashville, and his research collaborator Danny Riday, a practicing tattoo artist based in Les Eyzies, France. Welcome to you both to Science Friday.

AARON DETER-WOLF: Thank you so much, Flora. It’s great to be here.

DANNY RIDAY: Yeah, absolutely. It’s a pleasure.

FLORA LICHTMAN: OK, Aaron, let’s start with you. Let’s start with this new study on this ancient Siberian mummy. First of all, what did her tattoos look like? Can you describe them?

AARON DETER-WOLF: So this woman had a series of tattoos on both of her arms. Both of her forearms were tattooed with scenes of animals that, as you said, are tussling or engaged in fighting or battle. And then both of her hands also then have series of tattoos on them, on the thumbs and across her first knuckles of her fingers.

FLORA LICHTMAN: I mean, I’m looking at it. It’s so beautiful. First of all, I feel like anyone listening really should check it out. We’re going to put it on our Instagram, @SciFri, so you can see it. And it looks like three– I don’t know– tigers– would you say that?– going after a elk? How would you describe it?

AARON DETER-WOLF: Elk, deer, horse, deer. There’s this whole style of art has been called Scythian animal style. And one of the fun things about this has been that Danny, who has been collaborating with me for years on projects related to ancient tattooing, one of his practices is working in Scythian animal-style art. He does a lot of work there. And so his knowledge and view of these pieces was really just incredible and I think really important to the process.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Well, Danny, you’re a tattoo artist, and I know you’ve been collaborating with Aaron on this research for years. Do we know how they were made?

DANNY RIDAY: So our assessment that they were made via the hand-poked tattooing technique. That is holding a sharp utensil made of one end or more needle points between the first few fingers and poking by a repetitive series of pricks the tattooing implement dipped into pigment and then pricked into the skin.

AARON DETER-WOLF: And one of the cool things that Danny was able to identify by looking at these images is the presence of more than one tool, is that there are differences in the thicknesses of lines. That shows us that they were not just using a single tool, but they had at least probably a single point tool for very fine line work, and then a bigger tool that was made out of a cluster of needles that was used then for larger lines.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Like a tattoo kit.

AARON DETER-WOLF: Exactly like a tattoo kit. Yeah, people in the past, they used different tools to create different designs. The people that were doing this tattooing especially, they were not just one-offs. This was a generational practice. These people were craftspeople. And they had undoubtedly learned this through these long-term transmissions of knowledge going through generations.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Like any artist, probably.

AARON DETER-WOLF: Like any artist. Absolutely.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Yeah. Aaron, how many academics focus on ancient tattoos?

AARON DETER-WOLF: Oh, I think there’s at least seven of us.

FLORA LICHTMAN: [LAUGHS] How did you get into this, and why?

AARON DETER-WOLF: So I got my first tattoos when I was in graduate school. I went to graduate school to study Maya archaeology. And when studying the ancient Maya, one of the things that we’ve known about them for years is that they decorated and modified their bodies. They tattooed. They scarified their faces. They did all kinds of amazing things.

So working at archaeological sites in Guatemala and Belize, we would find obsidian blades that we could intuit and understand were used for body modification, were used for bloodletting or tattooing. But in my research and in my work as an archaeologist in North America, I had never encountered a tool that I could confidently say was used for tattooing. And as I began to look into this a little more, I realized that this was actually the case all over the world.

We know that ancient Egyptians tattooed, but we have no idea what tool they used. We know that Ötzi the Iceman tattooed in the European Copper Age, but we had no idea what tool was used to do that. And so, as an archaeologist, this really bothered me because what we’re supposed to be doing out there is understanding culture of the past. And if we can’t find these tools that are so important and are part of such an important process, it would be like not being able to find people’s houses, rgiht? How could we talk about the past if we couldn’t find people’s houses?

And so I wanted to understand why we weren’t finding these things and see if I could come up with convincing ways to identify them. There have been tattoo tools identified in the past in archaeological collections, but it’s kind of been, oh, these look sharp, and maybe they were using them to tattoo. And mostly those identifications are made by people who weren’t familiar with the practice and didn’t have tattoos themselves.

And I think that’s been a big part of this process, has been that working with Danny and working with other people who are tattooed and understand tattooing, that’s a sea change from the analysis that’s been done over the past century of tattoo tools and tattooed mummies because most of the people doing that work weren’t themselves tattooed. They might have seen tattoos, but they hadn’t gone through the experience, and they didn’t understand how these things actually worked at a physical level. And so I think that’s been a huge difference in what we’re able to bring to the table.

FLORA LICHTMAN: It’s like an oversight, basically.

AARON DETER-WOLF: Yeah, it would be like trying to write about cooking without ever having eaten with a spoon.

FLORA LICHTMAN: [LAUGHS] Danny, you’re a tattoo artist. Why do you care about the research side of this?

DANNY RIDAY: So I was trained as a traditional machine tattoo artist many years ago. And as I progressed as a professional tattoo artist, I kept finding that the older something was, the more interesting it was. A lot of my questions ended up leading towards how many traditional cultures were creating such intricate and outstanding works of art with such simple, traditional tools.

And it led me to completely abandon tattooing machines and pursue testing certain other implements on myself, like sharp rocks, cactus thorns, lemon tree thorns, and things like that. And as my questions about ancient tattooing gathered and mounted, I started trying to reach out towards people I thought might have the answers, and Aaron is at the top of that list.

AARON DETER-WOLF: Yeah. We met on Instagram of all silliness. And so yeah, we started talking. Oh, the iceman, isn’t it cool? He’s got 61 tattoos. How were they done? We have no idea. How were tattoos made in the ancient Andes? Yeah, we have no idea. And so we went from that to these questions of, well, how can we figure that out? And I think we’ve been able to make some really cool discoveries about how tattooing was done in the past and then, yeah, then learn about what that means for individuals.

FLORA LICHTMAN: I mean, I know that you both worked on a very famous iceman, Ötzi. He was extremely well preserved, over 5,000 years old. What did his tattoos look like?

AARON DETER-WOLF: So his are very different. So Ötzi’s tattoos consist of 61 separate marks that are just series of either short parallel lines or a couple of crossed lines that are on various places on his body. There’s some on his wrist, a lot on his lower legs, below the knees, the front of his stomach and chest area.

And one of the things that’s really interesting about Ötzi is we don’t understand them from an iconographic perspective. We don’t know what they’re trying to show us. We see them just as short lines. And I think because of that, it’s been widely assumed that his tattoos don’t mean anything, and that instead, they’re more likely to be therapeutic treatments of some kind than to convey a idea or a symbol.

FLORA LICHTMAN: That’s kind of a funny assumption because many people have geometric tattoos today, and obviously, they mean something to them.

AARON DETER-WOLF: Absolutely. No, I think that is a huge error that’s happened to this point.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Danny, I understand you did some of this experimentation on yourself to figure out how these ancient tattoos were actually made. Is that right?

DANNY RIDAY: Yeah, that’s correct. Aaron and I outlined a project in which we would gain a clear data set of what marks different tattooing implements leave. And I performed that tattoo series on my leg so that we would have a controlled sample.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Like what kind of implements?

DANNY RIDAY: So the different tools were– let’s see if we can remember them all– hand poking with an obsidian spike, tattooing with a single-point bone tool made of deer bone, tattooing with a single-point copper tool– because Ötzi the Iceman also had copper tools, we wanted to include a single-point copper tool– and also what we would call incision tattooing, making a series of small cuts and rubbing ink into it. And then the other two tattoos were performed by my friend and colleague, Mokonui-a-rangi Smith, who is a traditional Maori tattooer who has done the two-hand tapping tattoos, one with a multiple-point tool and one with a single-point tool.

FLORA LICHTMAN: As a layperson here, this sounds pretty hardcore, Danny. Which hurt the least? Was it painful?

DANNY RIDAY: Well, it’s an interesting question because we imagine these kinds of tattooing techniques as being very painful. If you observe hand tapping tattoos in progress that we would see across Polynesia, the outside observer really imagines something atrociously painful, when in fact, it’s quite the opposite. I find that hand tapping tattoos are the most relaxing to receive. Hand poking as well is quite un-severe, really. So pain is not really a factor when we consider the world of traditional tattooing.

I will say that the one that took the longest was the one that our colleague, Maya Jacobsen, coached me through, which was a traditional technique of the Arctic Circle and Inuit peoples, where an eye needle is passed through the skin in what we would call subdermal or skin stitch tattooing. It was an extremely difficult tattoo to perform. And the results give us a really clear idea of what that looks like, and now we can compare that many of our mummified human remains that we look at.

AARON DETER-WOLF: A lot of people when we talk about these things, that one of the first questions is, are you tattooed? And obviously, Danny is heavily tattooed. For me, I have become steadily more tattooed since engaging in this research. It turns out, when you hang out with tattoo artists, that you’re going to end up getting tattoos.

And I do have lines on my wrist that were hand-poked with a deer bone. Danny did incision tattooing below that, across my wrist, as a way for me to experience what that was like, and also as, again, another measure for what we can compare to preserved skin in the archaeological record and how we can help to see how those ancient tattoos were made.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

FLORA LICHTMAN: After the break, what do these ancient tattoos tell us about why we tattoo ourselves today?

DANNY RIDAY: It’s a reflection of our innate desire to modify not only our surroundings, not only our clothing, not only our tools, our weapons, our homes, but also our bodies.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

FLORA LICHTMAN: Do you see tattoos as a window into culture? What can they tell us? What can they teach us?

AARON DETER-WOLF: Oh, they can teach us all kinds of things. If you think about this as an iceberg, the tattoo is really just the thing that sticks up above the water. But underneath the water is this whole bigger, entangled mess of culture that results in someone being tattooed. And so what we’re really trying to do here is basically to dive down, to claw our way under what the tattoo itself is on the skin, and try to use that into a window to see individual parts of the past.

What was the experience of this individual person? How did they get this thing done? And then from there, branching out into questions like, well, who made it? Why is that significant? What can we say about the artists or about the people who made and use these tools? And can we identify them in the archaeological record? But I think there’s no limit to what we can learn about people individually and their culture writ-large from tattooing.

FLORA LICHTMAN: I want to go back to the Siberian woman for a moment. So when I look at this tattoo, it is hardcore. It’s beautiful, and it is also kind of hardcore. I know the Scythians were warriors. And they ride on horseback. Does this tattoo and seeing it in all its glory change or fill out our picture of these people or the role of women in this society?

DANNY RIDAY: So for the greater Scythian culture, women held a place of greater importance than they did in their neighboring cultures of ancient Greece, ancient Persia, and ancient China. The Scythians were more egalitarian in their cultural status. Women could become warriors or own property or own slaves.

But of course, this was something that would have taken a couple different sessions to perform. Obviously, the left arm was maybe one session of several hours. The right arm is at least two different sessions of several hours each. The image on her right arm especially is quite sensational.

None of this was done off the cuff. These were really carefully chosen, carefully selected, and masterfully tattooed images that this person, obviously, chose to have in a very visual part of their body. The forearm was something that they would be able to show to others, which I think is a pretty significant part as well.

AARON DETER-WOLF: Our co-author, Gino Caspari, who was the– he was the first author on this paper, some of the things he’s pointed out is that there are only seven examples of preserved skin from ancient Scythian cultures, and all of them are tattooed. So we have a very small sample, but 100% of the sample have tattoos. The other thing he’s pointed out that I think is really interesting is that none of the tattoos are the same. They share artistic style and themes, but they are not identical from person to person, even within the same tombs, even within the same site.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Wow.

AARON DETER-WOLF: And so that suggests that there may be a level of agency here that is separate from people just being awarded things for certain cultural reasons, that there might be some freedom of choice of the tattooer or the artist as to who gets what and why.

FLORA LICHTMAN: OK. In studying this across cultures, over time, what has this told you about why we tattoo ourselves at all? What do these ancient tattoos tell us about this modern practice?

DANNY RIDAY: I think what they give us an example of is really that to modify is human, and it has been since the beginning. It’s a reflection of our innate desire to modify not only our surroundings, not only our clothing, not only our tools, our weapons, our homes, but also our bodies. There are some body modifications that are so normalized that we don’t even consider them, like cutting our hair, trimming our fingernails, piercing our ears.

These are what normal humans look like to us. And I think that tattooing, we culturally might see it as something extreme in Western society now. But given the stretch of time that it has likely been a part of our everyday life as a species, it’s just us.

AARON DETER-WOLF: And one of the things that I’ve discovered in my research is that empires don’t tend to like tattooing. Cultures that are trying to conquer and homogenize other groups, some of the first things that they will eliminate in conquered societies are things like spoken language and body decoration and tattooing. And so the colonial era particularly was just really terrible for historical and Indigenous traditions around the globe. And there are a lot of people now working to recapture those traditions.

And I think that’s really important, too. We’re doing this work archeologically, but there are people who have tattooing traditions in their own heritage, unique Indigenous traditions who are working hard, sometimes alongside us and sometimes in parallel to us, to reconstruct these practices. And their work is really important to this as well.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Thank you both so much for taking the time to talk to me today.

AARON DETER-WOLF: Absolutely. Thank you so much.

DANNY RIDAY: It’s a great pleasure.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Aaron Deter-Wolf, archaeologist at the Tennessee Division of Archaeology, and Danny Riday, tattoo artist and independent researcher. You can see more of their research on Instagram, @archaeologyink. And if you want to see this ancient ink that we’ve been talking about, check out our Instagram, @SciFri.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Thanks for listening. Don’t forget to rate and review us wherever you listen. It really does help us get the word out and get the show in front of new listeners. Today’s episode was produced by Dee Peterschmidt. I’m Flora Lichtman. Thanks for listening.

Copyright © 2025 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Meet the Producers and Host

About Dee Peterschmidt

Dee Peterschmidt is Science Friday’s audio production manager, hosted the podcast Universe of Art, and composes music for Science Friday’s podcasts. Their D&D character is a clumsy bard named Chip Chap Chopman.

About Flora Lichtman

Flora Lichtman is a host of Science Friday. In a previous life, she lived on a research ship where apertivi were served on the top deck, hoisted there via pulley by the ship’s chef.