Coal Ash Pollution In Kentucky Lake Is Worse Than Expected

4:50 minutes

This segment is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. A version of this story originally appeared on WFPL in Louisville.

This segment is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. A version of this story originally appeared on WFPL in Louisville.

As a pending federal lawsuit over coal ash pollution in a Central Kentucky lake plods along, new details have emerged about the extent of contamination in the water.

In an affidavit filed last month in federal court, biologist Dennis Lemly laid out the results of fish sampling in Herrington Lake, a major fishing and boating site near Danville. Previous sampling by state regulators found high levels of the chemical selenium in fish tissue, but Lemly found evidence of additional damage to the lake’s fish and suggests the issue is far worse than the state’s assessment.

Selenium is a naturally-occurring element that can be toxic to wildlife in large amounts. Once it gets into a body of water it’s very difficult to eradicate. While it exists in nature, it’s also found in coal ash—the byproduct of burning coal for electricity.

And there are more than six years’ worth of documents showing contaminated water including arsenic and selenium leached from the ash pond at the E.W. Brown Power Station into groundwater and directly into Herrington Lake.

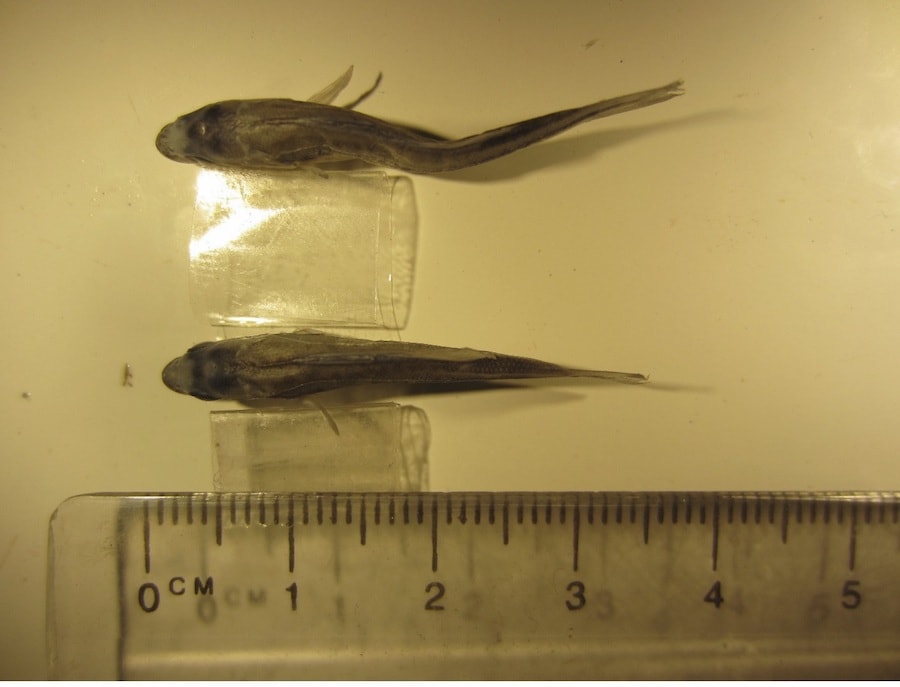

About 12 percent of the 548 fish Lemly tested showed serious physical deformities—everything from craniofacial deformities to skeletal problems.

“If you look at the background deformity rate, you might find 1 out of 200 fish that has a minor fin deformity,” he said. “In comparison, in Herrington Lake, over 1 out of 10 had deformities that were manifested in these major skeletal deformities.”

Meanwhile, the state’s sampling found nine out of 10 fish tissue samples taken in 2016 from the same lake exceeded Kentucky’s fish tissue selenium criteria.

And a spokeswoman for Kentucky Utilities, which operates the Brown plant, said the utility is not certain the large amounts of selenium that regulators have found in Herrington Lake are related to the Brown plant’s coal ash.

[These women are taking math to the next dimension.]

Environmental non-profit Kentucky Waterways Alliance, working with Earthjustice, filed the federal lawsuit in July after a WFPL story detailed extensive pollution from the coal ash landfill at the Brown Power Station. The Brown plant—operated by Kentucky Utilities—sits right on the edge of the lake. For at least six years, contaminated water left the site and ran off into the lake. Despite remedial measures, the problem continued, according to state records.

In January, the Kentucky Department for Environmental Protection formally cited Kentucky Utilities, fining the company $25,000 in civil penalties and requiring it to complete a corrective action plan.

That corrective action plan has yet to be finalized. The state received more than 400 comments–most from Sierra Club members—during the public comment period. All opposed the plan.

In the plan, Kentucky Utilities is proposing a study of all the potential sources of selenium that could have affected Herrington Lake, as well as a full fish analysis. This could take until 2018 or 2019—a delay many found unacceptable.

Kentucky Utilities’ plan to spend months trying to determine an alternative source of the pollution impacting Herrington Lake abdicates their responsibility for cleaning up the pollution they produced at their E.W. Brown plant. The Brown plant’s coal ash ponds lie adjacent to the lake and are almost certainly responsible for the selenium, lead, and arsenic found in the lake.

Kentucky Department for Environmental Protection spokesman John Mura said the state has yet to approve the corrective action plan, and he’s not sure on the timeframe. In the meantime, Kentucky Utilities has been given the go-ahead to begin their own tests of the fish in Herrington Lake.

“We are waiting on the results of further testing that is being done out there before we proceed,” Mura said.

Kentucky Utilities has requested a judge dismiss the lawsuit filed by Earthjustice, saying the issue is adequately addressed by the corrective action plan pending state approval.

Earthjustice attorney Thom Cmar is opposing KU’s motion to dismiss the lawsuit. The lawsuit and the corrective action plan are operating on separate tracks, and he said if the plan was beefed up a bit, it might address some of his concerns.

“If we could resolve this outside of a lawsuit, that would be better,” Cmar said. “But the only way that I can see that happening would be if the company was willing to take responsibility for its contributions to the very serious contamination we’ve seen in the lake and offer to take much more meaningful steps both to stop further pollution and clean up the pollution that’s already out there.”

Chris Whelan, spokeswoman for KU, said the company has begun its own fish sampling. She said other reports, like those issued by the Kentucky Division of Fish and Wildlife, contradict biologist Dennis Lemly’s findings.

“What we’re seeing from all the other reports is there’s no issue with the fish,” she said. “[The Division of Fish and Wildlife’s] annual performance report from 2016 says the fish are fine, and their 2017 fishing forecast says the fish are rated fair to excellent.”

Lemly said that makes sense—his study focused on small, young fish, while Fish and Wildlife looks at larger and older fish that anglers would target. He said the prevalence of skeletal deformities among the fish he sampled suggests the pollution has been an issue for a while—long enough to cause what are essentially birth defects.

“That gets back to the mechanism by which selenium poisons fish,” Lemly said. “It doesn’t poison the little fish after they hatch out of their eggs. It occurs because the adult fish consume high selenium in their diet. In other words, the selenium gets into the food chain.”

In the meantime, Lemly said selenium is nearly impossible to remove from a water body as large as Herrington Lake.

“Herrington Lake is contaminated,” he said. “And no matter if E.W. Brown stopped their discharge today, the selenium that is in that lake is going to continue to cause problems and accumulate in those fish and potentially poison them for a long, long time.”

The case in U.S. District court is currently awaiting a ruling from Judge Danny Reeves on Kentucky Utilities’ motion to dismiss.

Erica Peterson is an assignment editor and former environmental reporter with Louisville Public Radio.

IRA FLATOW: It’s now time to check in on the state of science.

SPEAKER 1: This is KERE.

SPEAKER 2: For WWNOW.

SPEAKER 3: St. Louis Public Radio.

SPEAKER 4: Iowa Public Radio news.

IRA FLATOW: This is where we take a look at science happening in the states. And this week we’re in Kentucky, a state that gets more than 90% of its power from coal plants. But a fight’s been brewing over what happens to the waste products from burning coal and how the state regulates it.

Here with me is Erica Peterson, an assignment editor and former environmental reporter for Louisville Public Media. She’s been covering this story. Nice to have you.

ERICA PETERSON: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s talk about this story. What exactly is coal ash, for people who don’t know what it is?

ERICA PETERSON: Yeah, sure. Coal ash, it’s also called coal combustion residuals sometimes. It’s basically what’s leftover when you burn coal for electricity. There’s a lot of stuff that goes up the stack.

But as more and more pollution controls are put on more and more of it remains in coal ash. And much like coal, this is stuff that’s full of toxic things, like arsenic, selenium, lead, mercury, lots of nasty stuff.

IRA FLATOW: So where does it go then?

ERICA PETERSON: Well, a lot of it, some of it is recycled. But for the most part, power plants store it. And they start either in dry landfills or in wet ponds. And both cases, they’re huge landfills that are like mountains or they’re very large ponds.

And this has been a problem in the past because until the federal law required certain things in 2015 there were no liners that had to be required. So at a lot of these sites there were leaching problems, where these chemicals were getting into groundwater or surface water.

IRA FLATOW: So in Kentucky there is disagreement over some of the new regulations for how these disposals happen.

ERICA PETERSON: Yeah. For the past year, there’s been this debate going on in Kentucky. The federal coal ash regulations, they are a lot diff– [INAUDIBLE] lot of environmental regulations. They’re kind of more like lake standards.

They’re saying, we’re suggesting these specifications. And states are expected or urged to incorporate those into their existing state standards. So what Kentucky tried to do is rather than incorporate them into our existing regulations they basically scrapped the existing regulations and is proposing to just incorporate these looser guidelines, which has annoyed some people who are concerned about this.

Because pretty much before, if you wanted to build a coal ash landfill you had to do a whole bunch of stuff. There was a permitting program. You had to get state engineers to sign off on where you’re going to monitor, where it’s going to be built, all these specifications. And under the new proposal, what they would be allowed to do is basically go ahead and build it. And if there are any problems that the state or citizens discover after the fact, they can be sued for it, which might be too late at that point.

So that also has drawn a lawsuit. And this is how Tom Fitzgerald, who’s a prominent environmental attorney in Louisville, described it back in January.

TOM FITZGERALD: It’s the Wild West basically. And you get to control the design, the construction, the operation, the closure, the post-closure. And the only time the state is going to become involved is after you screw up, if they find out about it.

IRA FLATOW: So where do we go from here? What do you expect to happen?

ERICA PETERSON: Well, that lawsuit is still pending. Fitzgerald and the Kentucky Resources Council have sued the state and they’re waiting on a judge to determine what’s going to happen.

IRA FLATOW: So we can expect then looser regulations suspended pending the lawsuit, the outcome of the lawsuit. And this is something that you’ve been following for years, right? You’ve been an environmental reporter.

ERICA PETERSON: Yeah. Yeah, I have. And it’s a really big issue. And one of the reasons that I think Fitzgerald and other people are so concerned about this is it’s not like Kentucky has done that great job controlling pollution from these sites up until now.

IRA FLATOW: All right. Thank you very much for taking the time to be with us today.

ERICA PETERSON: Thanks a lot.

IRA FLATOW: Erica Peterson, she’s an assignment editor and former environmental reporter, as she says, for Louisville Public Media, who has been covering this story.

And we’re going to take a break. And after we talk about all that burning coal, well, how is the planet warming? And instead of cutting emissions, the House Science Committee is interested in another idea and that is geoengineering.

We have talked a lot about geoengineering, what it is, what kinds of things to expect on geoengineering. And it’s amazing that, as one headliner wrote, the House Science Committee actually talked about science this time it met.

We’ll talk about it with people who were there after the break. Stay with us. We’ll be right back.

Copyright © 2017 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.