‘Dear Science Friday, Can You Study The Asp Caterpillar?’

16:27 minutes

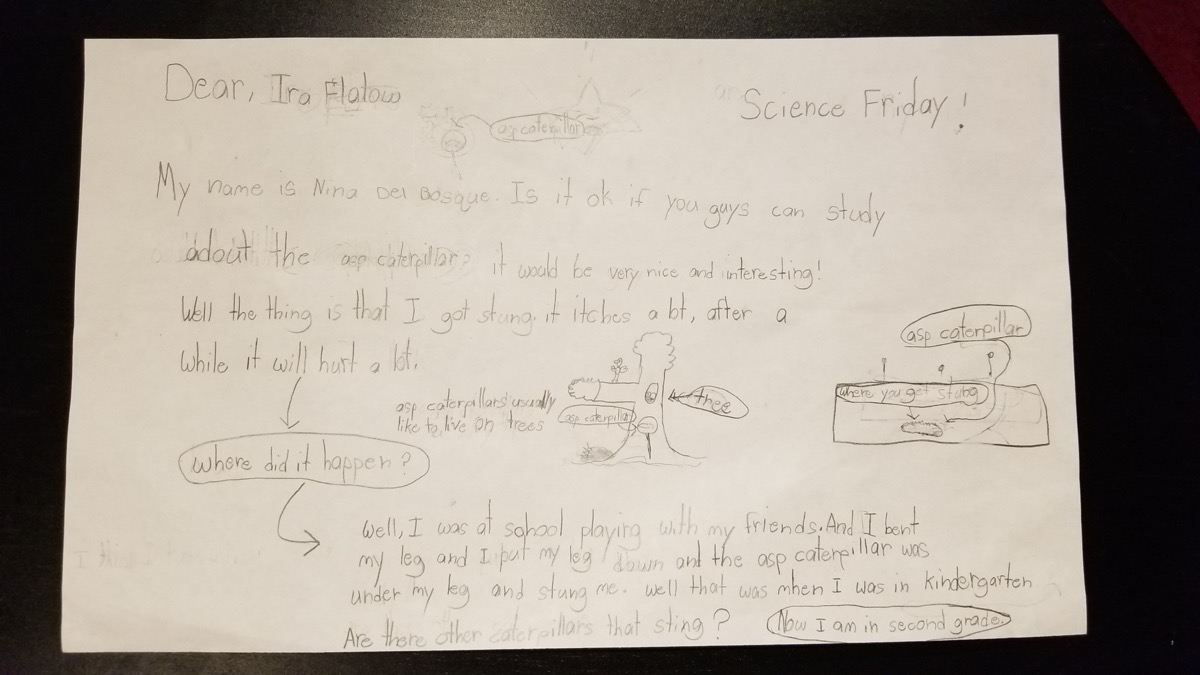

Caterpillars might be the squirming, crawling larval stage of butterflies and moths, but they have defenses, behaviors, and lives of their own. Second grader Nina Del Bosque from Houston, Texas was stung by an asp caterpillar. She wanted to know about other stinging caterpillars in the world and what role they play in the ecosystem—so she sent Science Friday a handwritten letter with her questions. We invited Nina on the show with biologist David Wagner, author of Caterpillars of Eastern North America: A Guide to Identification and Natural History, to talk about the stinging asp caterpillar, the woolly bear, and all things caterpillar.

Caterpillars might be the squirming, crawling larval stage of butterflies and moths, but they have defenses, behaviors, and lives of their own. Second grader Nina Del Bosque from Houston, Texas was stung by an asp caterpillar. She wanted to know about other stinging caterpillars in the world and what role they play in the ecosystem—so she sent Science Friday a handwritten letter with her questions. We invited Nina on the show with biologist David Wagner, author of Caterpillars of Eastern North America: A Guide to Identification and Natural History, to talk about the stinging asp caterpillar, the woolly bear, and all things caterpillar.

View a few of these unique critters below.

We’re recruiting for the 2019 SciFri Educator Collaborative! Build awesome science activities, work with SciFri staff, and get mentorship from fellow educators. We will be accepting applications until Friday, January 4th, 2019 5 PM EST.

Nina Del Bosque is a 2nd grader at the Poe Elementary School in Houston, Texas.

David Wagner is the author of Caterpillars of Eastern North America: A Guide to Identification and Natural History. (Princeton University Press, 2005) He’s also a professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Connecticut in Storrs, Connecticut.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. You know, we have great listeners. And we get a lot of letters, and e-mails, and questions from you curious science geeks. But we got one a few months ago that really stuck. It was from a young scientist who had an encounter with a caterpillar that made her curious. This is her letter.

NINA DEL BOSQUE: Dear Ira Flatow, my name is Nina Del Bosque. Is it OK if you guys can study about the asp caterpillar? Well the thing is, I got stung. It itches a lot.

Well I was at school playing with my friends and the asp caterpillar was under my leg and stung me. Are there other caterpillars that sting?

IRA FLATOW: Nina Del Bosque, a seven-year-old seventh grader at Poe elementary school in Houston, Texas. So we wanted to hear what other caterpillar questions she had. So we’ve asked her to come on the show. Welcome, Nina.

NINA DEL BOSQUE: Hi.

IRA FLATOW: Tell us about where you were. What were you doing with your friends when this asp caterpillar stung you?

IRA FLATOW: I was praying with my friends. And I was looking for centipedes. So I was sitting. And So I put my leg down on the ground. And the asp caterpillar was right right under my leg. So I put pressure on my leg. And so it stung me, because I was in my leg. And, yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Had you ever seen an asp caterpillar before?

NINA DEL BOSQUE: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: And why were you interested in this caterpillar?

NINA DEL BOSQUE: Because when I got stung it itches a lot. And after it’ll hurt a lot. And I was interested how it works. The caterpillar how it stings us and–

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, I understand that. Because I’m interested in things like that, too. I understand that you also like ladybugs.

NINA DEL BOSQUE: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: What do you like about them?

NINA DEL BOSQUE: Because I hold one before. And they crawl around. And I like it because it kind of feels ticklish because they crawl around very fast. And I like it. And also they look very cool.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Do you ever try to rescue these bugs?

NINA DEL BOSQUE: Yes, I have one. So I have a box and it’s called Ladybug Land. And I’ve captured one. And we found it at my school. And it was injured. So I picked it up carefully and I put it in my box. And so I still have him. And I give him food and water once in a while. And I take care of him a lot.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, that’s nice. I’m going to bring on another caterpillar friend to help us, an expert to help us out. And answer some of your questions. I know you have some questions for him.

And if you have noticed any interesting caterpillars in your yard, I’m talking to my listeners, and then you have questions about them, we want to hear from you, too. Our number is 844-724-8255. You can also tweet us @SciFri.

David Wagner is a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Connecticut in Storrs. And he’s also author of Caterpillars of Eastern North America, a Guide to Identification and Natural History. Welcome to Science Friday.

DAVID WAGNER: Great to be on.

IRA FLATOW: So you study the entire lifecycle of caterpillars? So the butterflies and moths they become, too?

DAVID WAGNER: Absolutely. Yeah, the egg, the caterpillar, the pupa or chrysalis, and the adults.

IRA FLATOW: And so why are caterpillars so interesting to you?

DAVID WAGNER: I think they’re beautiful. I think they’re maybe the largest creatures in all of North America where there’s no field guides or identification guides up until about 10 years ago. And being a professional entomologist I thought I’d get help out there. And provide something so people could identify what was in their gardens and in the forest when they’re on walks.

IRA FLATOW: Do you have your own favorite caterpillar?

DAVID WAGNER: Well I sort of do. There’s something called the spun glass slug. And it’s an absolutely magnificently beautiful creature. It’s small, but you can actually see through part of the body. This beautiful pale green, blue green color. Actually it can sting, though like Nina’s caterpillar. But it’s so small that it’s really innocuous.

IRA FLATOW: Now I understand that like Nina, you actually got stung by an asp caterpillar. But you did it on purpose.

DAVID WAGNER: Well, I knew they stung. And I’m interested and these sorts of things. So I decided to press one into my arm. And it was the most painful insect sting I’ve ever had. And it’s most frightening. Because normally when you get stung or bit by something it hurts right away. And you’re alarmed. But this thing, the pain intensity kept growing and growing over two hours. And you don’t know when it’s going to stop. So that that was really off putting and quite frightening, actually. And very painful. It didn’t stop hurting for hours.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Nina do you have any other questions you’d like to ask now? Go right ahead.

NINA DEL BOSQUE: Yes. Can we use poison of the caterpillars to make medicine?

DAVID WAGNER: Well I don’t know of any examples of that. But we certainly will be studying that. But there are different compounds produced by caterpillars that are used in medicines.

So there are certain caterpillars that produce chemicals that kill bacteria. So potentially, we could use these as antibiotics.

IRA FLATOW: Have you got another one, Nina? Go ahead.

NINA DEL BOSQUE: Are there– how can you tell if caterpillars are safe or dangerous?

IRA FLATOW: Oh, I want to know that one, too.

DAVID WAGNER: Yeah, that’s a good question. So normally, if they’re green and brown and trying to blend into the background and disappear, then you can be pretty sure that they’re trying to hide from birds. And those are probably going to be harmless. And, you know, if birds are eating them, people probably could, too, but we don’t eat caterpillars normally.

But the ones that are brightly colored, so let’s take yellow, orange, red caterpillars, particularly if they have some accentuating black and white color, they’re trying to tell you something. They’re trying to warn you away. They’re your Clint Eastwood caterpillars. And they’re possibly going to sting you, or spray something at you, or maybe they’re mimicking another dangerous caterpillar.

But Nina, if you and I were to go into the Amazon and walk together, and if we saw really brightly colored animals when we’re in the jungle, walking together, we should generally stay away from those because they’re trying to advertise and tell us that they’re dangerous. But the other caterpillars, the ones that are just earth colors, greens and browns, they’re probably very safe and you can pick them up.

IRA FLATOW: Nina, have you seen any caterpillars you’d like to ask about?

NINA DEL BOSQUE: Yeah. So we went at Mexico and we’re planning on going to Mexico, and see monarch butterflies. And also there might be some caterpillars and we’re going find out what kind of caterpillars they are and look at them and enjoy.

DAVID WAGNER: Yeah, the monarch caterpillar’s a splendid creature. It’s very handsome. Actually, the website for this show might have a picture of a monarch caterpillar on it. It’s a great pet for two or three weeks. They feed up right away, easy to rear, and it’s really wonderful to watch the metamorphosis. I think it’s really great and healthy for kids to see growth and development and change. I think it’s a great allegory for their own personal development. But it’s really wonderful with the monarch because they have this see-through chrysalis, so you actually get to see change and growth, and you get to watch it turn into the adult and then break out of its pupa. And then you can let it go outdoors to continue on its journey.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s go to the phones. Let’s see if we have any– yeah, here’s a phone call from Rachel. Hi, Rachel, welcome to Science Friday.

RACHEL: Thank you, thank you. Such an interesting discussion. I’m really in awe of Nina, the young scientist. I have a question because you said if we’ve seen any kind of interesting caterpillars lately, and I’ve seen some this year that I haven’t seen before in my yard as the leaves on the deciduous trees have been falling. A couple times on cold days, there’s one that has, what looks like long brown, almost bronze-colored hairs. And then it has some– and then part of the caterpillar is black. And when I’ve seen them, they look almost like they’re folded over in half, and one of them I thought might have been trying to form a chrysalis or something.

And so when I’m seeing them, first I don’t know what they are, but I’m wondering where do I put them to keep them safe? I’ve seen them on the driveway. I’ve seen them on the porch by the house. And I’m not sure where they were trying to go to or where they were before they arrived there.

DAVID WAGNER: Well, you could figure out what they were if you bought my book, but–

[LAUGHTER]

But in any case–

RACHEL: I know there’s a website for this, but I’m just too lazy, you know, [INAUDIBLE] hey, have you seen this? I said, maybe someone else can tell me what it is without me having to go through [INAUDIBLE].

DAVID WAGNER: One of the wonderful things about living in eastern North America is that we have a great amount of wildlife in our woodlands and forests, and really, within a mile of our homes, we can expect to find about 1,000 species of butterflies and moths, each with their own unique kind of caterpillar. So I really can’t say which one it was.

It sounds a little bit like a monkey slug, and they’re just fabulous creatures with lots of hairs on them, and kind of amorphous and hard to recognize, and maybe it was spinning a cocoon on the leaf, but it’s hard for me to say. But I would just put it out of the way of any vehicles while walking past it, that sort of thing, and let it go on its natural cycle.

IRA FLATOW: Not afraid to pick it up, then.

DAVID WAGNER: You know, you can pick up even these dangerous ones that sting if you do it very, very gently. So they’re using these things as a defense, and never do they actively sting like a bee. So it’s basically from poor handling. And the other thing that happens with gardeners is that the caterpillar actually drops into the clothing. And that can be quite serious with the asp that stung Nina. It’s a miserable thing, and it happens– the pain will last up to two days, and every joint, upstream and downstream where you’ve been stung, will feel arthritic.

IRA FLATOW: We have a tweet that came in. Is there any statistical data to support the old wives’ tale about the width of a woolly bear’s bands and the upcoming weather? And we have a video on our website about that. Is there any data about that? Jennifer wants to know.

DAVID WAGNER: Well, generally, that’s pretty weak. And it– there’s probably just more genetic variation in terms of the amount of orange and amount of black in woolly bears. And they range, actually, all the way from all black to all orange. But there might be a certain correlation that in certain years the caterpillars don’t get as far along because winter comes early, and they would potentially have, let’s say, less orange. And then as– in another year, where it was a mild winter, they would get through their development a little further and have more of the other color.

IRA FLATOW: Nina, I’m going to you for another question after I tell everybody that I’m Ira Flatow and this is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. Nina, give us your next question if you could.

NINA DEL BOSQUE: How do the feet work? With hooks or claws or stickiness? And also, how many feet do they have?

DAVID WAGNER: Well, that’s the easy part. They have about eight different pairs. But in answer to your first question, it’s all of the above. Some caterpillars have claws. In fact, they almost all do. They have the six legs that all insects, even your ladybugs have, up front, but we kind of think about the fleshy legs in the abdomen that hold up the abdomen as the caterpillar legs, and they have about five pairs of those. And they have hooks on the end. They look just like a little crochet hook on the end.

And generally, that’s a way for them to engage whatever they’re sitting on so they don’t get pulled off by a bird. But what you don’t see is oftentimes they use their silk. They have the little silk spinneret. All the silk on the planet comes from caterpillars. But they spin little pieces of silk where they’re walking and where they like to rest and where they’re eating, and you don’t know it, but they’re taking their little hooks and hooking into that silk so they don’t fall off the leaf or don’t get pulled off.

IRA FLATOW: Now, I know that you call caterpillars the hamburger meat of the animal world.

DAVID WAGNER: I think that if you’re going to go out into a Connecticut or Houston forest, and you’re just going to look at all the insects that you could find, most of the weight, or most of the mass, the meat, what’s there for other animals, birds, foxes, coyotes, mice, and what have you, would actually be caterpillars. So they’re sort of– they’re tethering together our terrestrial ecosystems. They are what makes a baby bird. So if your listeners love songbirds, you have to appreciate that caterpillars play a really important part in building that baby bird each spring.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s go to the phones to Ross in Oakland. Hi, Ross.

WOMAN: This is Ross.

IRA FLATOW: Hi there, go ahead.

ROSS: This is the big story. It’s a little bit short and this big caterpillar that looks like a dragon was really big and it was right in the grass.

WOMAN: And did we find out, is it poisonous, or not poisonous?

ROSS: Not poisonous, but it had those spines.

WOMAN: And what did it look like?

ROSS: It looked like make a dragon.

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

WOMAN: And then what does it turn into?

ROSS: The biggest moth in North America.

DAVID WAGNER: Oh, the hickory horned devil. It’s a magnificent moth. Some of them get over five inches in wingspan, and they’re absolutely enormous. And they’re harmless, like Ross, her child said. They have been declining, though. So I don’t know if you’ve heard about much of the insect loss, but they’re one of the groups that seems to be losing ground against all the changes that have been brought by humans.

IRA FLATOW: All right. Thank you, Ross, for that excellent question. Nina, do you have anything left, or are you just going to go out looking for some more caterpillars?

NINA DEL BOSQUE: I have one more question.

IRA FLATOW: Go ahead.

NINA DEL BOSQUE: Do caterpillars sense better with eyes or antennaes, or smell?

DAVID WAGNER: That’s a good question. And I don’t know exactly there. Their eyes– they can see you. So they have image-forming eyes on the side of their head, and sometimes when I walk into the lab I can see that my caterpillars look at me. But in general, their eyesight’s probably not too sharp, and their antennae are much smaller, right? So they’re not like the great big antennae of the monarch or the hickory horned devil. They’re very tiny. So I don’t think they do too much.

And their mouth parts don’t do too much either. So I think most of what they can do or sense is actually movement, or pressure. So they can sense that a predator is sneaking up on them if they hear– they feel wind, maybe. Or if their leaf starts to shake they can feel it through their feet. So I think they mostly do things by touch.

IRA FLATOW: David, thank you very much for taking the time to be with us today. David Wagner, author of Caterpillars of Eastern North America: A Guide to Identification and Natural History. And Nina Del Bosque is a second grader at Poe Elementary School in Houston. Thank you for joining us Nina. Have a good weekend.

NINA DEL BOSQUE: Bye.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.