America’s Elder Care Has A Problem

28:31 minutes

This segment is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. Read articles by station reporters that take a look closer at issues impacting nursing homes in California, Kansas, and Massachusetts.

This segment is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. Read articles by station reporters that take a look closer at issues impacting nursing homes in California, Kansas, and Massachusetts.

Since the pandemic began, long-term care facilities across the country have experienced some of its worst effects: One of the first major outbreaks in the U.S. began in a nursing home in Washington state. Since then, the virus has ravaged through care centers across the country—as of September 16, more than 479,000 people have been infected with COVID-19 in U.S. care facilities.

But COVID-19 is merely adding stress to an already fragile system of long-term care facilities—including nursing homes, assisted living, and other rehabilitation centers. Coronavirus outbreaks have only exacerbated pre-existing problems, such as overworked and underpaid staff, limited funding, and poor communication with families.

“The sad thing is that this [pandemic] is going to expose the incredibly tragic consequences of some nursing homes being less resourced—and less prepared for situations like this,” says Celia Llopis-Jepsen, health reporter for the Kansas News Service.

In Kansas, more than half of the state’s COVID-19 deaths have been among nursing home residents, with 50 active outbreaks in long-term care facilities as of August 26. In the midst of these challenges, facility administrators have reported major issues with staff turnover and availability. Lack of personnel has been a fundamental problem in long-term care for years.

“There aren’t requirements that you have to have a lot of people on duty, and that’s a problem,” says Molly Peterson, science and environmental reporter for KQED in San Francisco. “That’s a problem with a pandemic and you need to separate populations of people. It’s a problem if you have older people who are at risk [due to pre-existing conditions] and you need to get them out of harm’s way.”

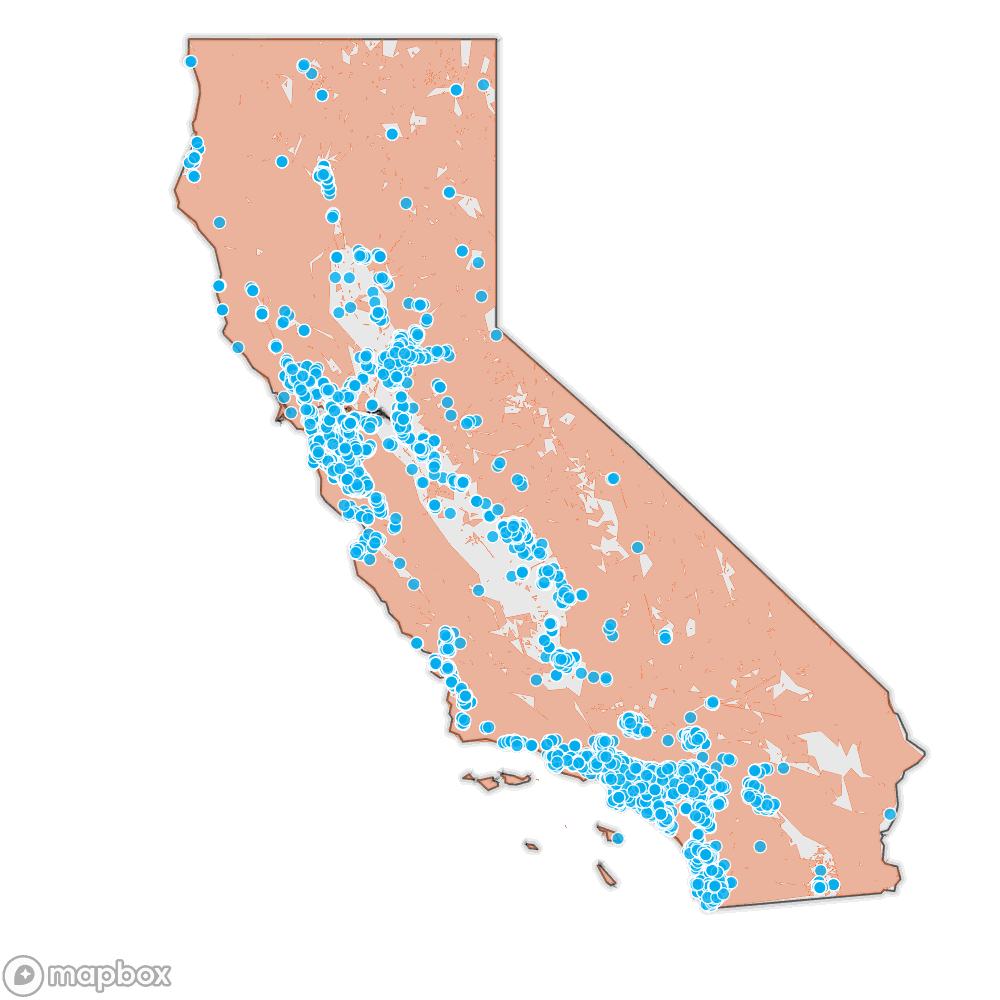

When facilities are so vulnerable, COVID-19 won’t be the only hazard that becomes a problem. A recent KQED investigation, Older and Overlooked, found that thousands of long-term care facilities in California are also located in high risk wildfire areas. Many of these facilities have inadequate or poorly communicated evacuation plans—Peterson spoke to some staff who said they weren’t aware a plan even existed at their facility.

“These are systems that are not adequately prepared to take into account all the changes that we’re seeing.”

In California, facilities are currently fighting two battles: More than half of the skilled nursing facilities at risk of wildfires have reported cases of COVID-19, Peterson reports. This adds to the growing concern over this year’s devastating wildfire season, with fires currently threatening facilities in Vallejo and Fairfield.

“There’s been a growing national conversation around climate hazards and how they can turn into disasters for these vulnerable people,” says Peterson, adding that climate scientists say we should be taking a closer look at the systems that impact and care for people. “These are systems that are not adequately prepared to take into account all the changes that we’re seeing.”

Re-thinking long-term care will become even more important as our population ages. In the United States, the number of those 85 and older is expected to nearly triple from 6.7 million in 2020 to 19 million by 2060, according to the Population Reference Bureau’s analysis of U.S. census data. This is the demographic that most relies on long-term care facilities—but experts doubt the current system can support the demands of our growing elderly population.

“We’re an aging country with lower fertility rates, and so the pressures on caregiving are not going to go away,” says Robert Applebaum, a gerontology professor and director of the Long-Term Care Project at Miami University in Ohio. “The structural problems are just phenomenal.”

These fragile systems need to be better equipped for emergency situations, whether a climate disaster or a pandemic. “It’s really a whole system of support and services serving a very broad group of people that have very diverse needs,” says Sonya Barsness, a gerontologist and industry consultant based in Washington D.C. She says there needs to be a shift “from an institutional medical model to a model that truly honors and serves the people who live and work in it.”

In this week’s segment hosted by radio producer Katie Feather, Celia Llopis-Jepsen and Molly Peterson give a closer look at the issues inside nursing homes in Kansas and California. Then, Robert Applebaum and Sonya Barsness dig into the root of the systemic problems, and look for solutions that can build better long-term care for our aging population.

Many of these trends are reflected in stories shared by families and residents in long-term care facilities. We asked listeners to voice their experiences with nursing homes on the SciFri VoxPop. Listen to their stories below.

Janet from St. Louis, Missouri: My mother was in a nursing home-rehab facility, and it was just horrible. The occupational and the physical therapy was not designed to her particular needs and lifestyle prior to admission, and there was always the threat of her being discharged if she didn’t cooperate. Also, they sent a $12,000 bill after she’d passed.

Dan from Raleigh, North Carolina: My mom was in independent living for two years, but declined to where we moved her into a nursing home. She rapidly declined and past three months later. I’m very angry about my mother’s care in the last three months of her life. I know there’s good people out there and it’s a tough job, but my mom did not get the care she needed. Staff were apathetic and patient injuries went untreated. It’s difficult for me to talk about.

Nalini J. from Scarsdale, New York: I am Nalini Juthani and I’m talking about my experiences with my mother who received care in a nursing home for three years. She passed away two months ago. The experiences and the care that she received was incredible.

“I know there’s good people out there and it’s a tough job, but my mom did not get the care she needed.”

John M. from Pleasant Hill, California: I’ve had all four parents in assisted living, although it’s been sort of okay. The food is generally just terrible. The staff turnover is very high because the wages are low, so you get inconsistent help. The so-called activities directors usually treat the residents like infants, so you get very little intellectual stimulation. The management is usually more interested in the bottom line than the real care of their residents.

Matthew from Washington, D.C.: I have two parents now that have been in nursing homes and passed away at the end of their lives while in the care of the nursing homes. The facilities have been fantastic. They have not had any issues there. Maybe sometimes the food is a little bit cafeteria-like, but I’ve gotten to eat with my parents in those situations.

Kristi Lauren L. from Salt Lake City, Utah: My mother-in-law’s partner of 20 years, got COVID in a nursing home, and we weren’t able to be with him or say goodbye when he passed away. When we waved to him outside of the window, he wasn’t aware of who we were and look startled.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Celia Llopis-Jepson is the host of “Up From Dust” from KCUR Studios in Kansas City, Missouri.

Molly Peterson is a science and environmental reporter at KQED in Los Angeles, California.

Robert Applebaum is a professor of Gerontology and the director of the Long-Term Care Project at the Scripps Gerontology Center of Miami University in Oxford, Ohio.

Sonya Barsness is a gerontologist and industry consultant based in Washington, D.C..

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. A bit later in the hour, we’ll talk to a volcanologist studying volcanoes from North Korea to Antarctica and even on other planets.

But first it’s time to check in on the state of science.

(AUDIO RECORDING): This is KERA– for WWNO– St. Louis Public Radio– KKNO News– Iowa Public Radio News.

Local stories with national significance. COVID-19 has forever changed traditional institutions as we once knew them– schools, the workplace, hospitals, and nursing homes. Our long-term care facilities have seen some of the worst outbreaks of the disease. And, while nursing homes may be under scrutiny now, experts say problems with the system existed long before this virus. Science Friday producer, Katie Feather has more.

KATIE FEATHER: Ask anyone who knows something about nursing homes and long-term care facilities in the US. And they’ll tell you that the cracks were there even before the pandemic. The families of residents in nursing-homes know this all too well. We asked our Science Friday listeners to tell us their experiences with nursing-home care on the Sci-Fri VoxPop app. And this is some of what they shared.

DAN: My mom was in independent living for two years but declined to where we moved her into a nursing-home. She rapidly declined and passed three months later. I’m very angry about my mother’s care in the last three months of her life. I know there’s good people out there. And it’s a tough job. But my mom did not get the care she needed. Staff were apathetic and patient injuries went untreated. It’s difficult for me to talk about.

JOHN: I’ve had all four parents in assisted-living. Although it’s been sort of OK, the food is generally just terrible. The staff turnover is very high because the wages are low. So you get inconsistent help. The so-called activities directors usually treat the residents like infants. And so you get very little intellectual stimulation. And the management is usually more interested in the bottom-line than the real care of their residents.

JANET: My mother was in a nursing-home slash rehab facility and it was just horrible. The occupational and physical therapy was not designed to her particular needs and lifestyle, prior to admission. And there was always the threat of her being discharged if she didn’t cooperate. Also, they sent a $12,000 bill after she passed.

KATIE FEATHER: That was Dan from Raleigh, North Carolina, John from Pleasant Hill, California and Janet from St. Louis, Missouri.

Poor communication, overworked staff, inadequate care, and lack of financial support were common themes among the stories we heard. So we wanted to check in on two states– Kansas, where almost half of all COVID-related deaths have been linked to long term-care settings and California, where nursing-homes are fighting a war on two fronts– a pandemic and this month’s devastating wildfires.

Joining me now, to take a deeper look at what long-term care facilities in these two states are currently up against are my guests.

Molly Peterson is a science and environmental reporter for KQED in San Francisco, California. She’s based in Los Angeles.

Celia Llopis-Jepsen is a health reporter for the Kansas News Service. Welcome to Science Friday.

MOLLY PETERSON: Thank you, happy to be here.

KATIE FEATHER: Molly, I want to turn to you first because, even though nursing-homes have been dealing with the coronavirus for the past several months, facilities in California have been facing a much more pressing threat with these wildfires.

MOLLY PETERSON: Right, we’ve got wildfires– we’ve– as of today we’ve got wildfires burning about 3% of the state’s land so far this year. And we’ve got a couple more months of this season left to go. We’ve got a lot of facilities that are evacuating, some of them to multiple locations, and some of them for the second or third time this year already.

KATIE FEATHER: I gather from your reporting that there isn’t a set of policies describing how facilities would evacuate residents, if there was a wildfire.

MOLLY PETERSON: In Santa Rosa, in fires a couple of years ago, we saw assisted-living facilities where residents were left behind by staffers. They didn’t have access to keys. They didn’t know how to get the vans– to get them into vans. They didn’t know where to take people locally because the fire was coming so close. There wasn’t an easy evacuation location.

And, generally speaking, those facilities were unprepared. They didn’t get into a lot of trouble. These are state-regulated assisted-living facilities, not health-care facilities. And there weren’t a lot of requirements on these facilities. That’s since changed. But we’re talking about a lot of facilities around the state, some of which only have six beds and may not be ready for a rapidly-moving fire to come their way.

KATIE FEATHER: It’s just so surprising that there wasn’t a policy in place earlier. And it seems like it takes the families by surprise, too. You have a story about the Tubbs Fire which burned down one senior-care center, Villa Capri. And you spoke to a family, a daughter and her mother who was living in the facility, and who had been abandoned by staff there.

MOLLY PETERSON: That’s right. Another member of my team, April Dembosky at KQED, spoke to Beth Eurotas-Steffy and her mother Alice Steffy. Alice was rescued by yet other family members, of other folks at that facility.

BETH EUROTAS-STEFFY: I was just so angry. I can’t even really put into words how angry I was and how disappointed in a state agency whose job it is to get up every morning and protect people like my mom, living in a facility like that. And they failed them.

MOLLY PETERSON: What I think is interesting is these facilities, when they’re planning, really rely on volunteer support. Staffing is minimal and, at night, there were only– even if everyone had stayed– there were only a handful of folks there for a facility that had several-hundred residents. So getting people out really was this community effort.

KATIE FEATHER: And, looming in the background of all this, we’re still dealing with the coronavirus. So how are these facilities able to do all this evacuation and removal of residents in light of COVID-19?

MOLLY PETERSON: Yeah, they’re making it up as they go along. They have not had a lot of guidance from state and federal regulators. The guidance is sort of generally for social distancing.

But, for example, in San Luis Obispo, in the Central Coast of California, there was a fire in June that caused some small assisted-living facilities to evacuate. When those facilities were given the all-clear to go back, some of the residents had essentially broken quarantine, gone home with family members, to be safe.

The other residents had stayed quarantined and segregated and separate in hotels. How do you rejoin those populations safely, if you don’t have a series of testing protocols or plans for how to isolate people?

In some states, testing availability is a real, real issue. In California, in some places you can drive up and get a test and get a result the next day. And in some places you have to wait. And that’s been a challenge for facilities here, too.

KATIE FEATHER: And one of those places where testing has been an issue has been in Kansas. So I want to turn to Celia. What’s going on at the facilities there in your state?

CELIA LLOPIS-JEPSEN: Well, it’s exactly as you mentioned. They’re struggling with access– consistent affordable access– to testing with fast results. It varies by where you are in the state. It varies even within a single city, depending on the week and how slammed the hospitals and labs in your area are. So it– half a year into this pandemic– nursing-homes are frustrated that they still have to deal with this.

KATIE FEATHER: And we heard from some of our listeners about high turnover of staff. And you mentioned in some of your reporting that the lack of testing is exacerbating those problems.

CELIA LLOPIS-JEPSEN: Yeah, so that’s a good example. So, for example, I talked to one nursing home in Topeka. And, in an average week, they have maybe six staff members that have a sore throat or some symptom that is concerning and makes them think, OK, don’t come into work. We need to check if you have COVID-19.

They fan out to their various doctor’s offices or hospitals. And maybe some of them get lucky and get test results really fast, and they’re back to work in 48 hours. And maybe someone else that went to the other hospital in town, that person ends up waiting five days to find out that they’re clear.

So, in the meantime, while you have half a dozen people out, the other employees are working even longer shifts. So more than 60 hours a week to cover for this situation. So there is a real risk of burnout and exhaustion when this is going on week after week.

KATIE FEATHER: We’ve all heard the stories of residents dying alone in these facilities. You also pointed out in one of your stories that, even if residents aren’t getting sick and passing away, they’re still isolated. And they’re alone in their rooms. And they can’t see their family members. And that’s having an impact on their mental health.

CELIA LLOPIS-JEPSEN: Yeah, it is absolutely. And now I think that access to family varies on where you live. I just talked to one nursing-home today in a very rural area of the state that still, since the beginning of the pandemic, has not allowed any visitors in because they’ve had one issue after another.

And I’ve talked to nursing aides who’ve said that, when their residents that they work with are really isolated, you can see that people feel like giving up. I mean, this is going to sound brutal, but I had one nursing assistant cry while telling me this. She felt like people give up because they feel like there’s not a reason to live because they’re not having the same contact that they’re used to, leaving the nursing home every weekend to have dinner with their families.

KATIE FEATHER: So how will we emerge on the other side of this? Will things get better in these facilities now that we’re looking at them and realizing their need for support?

MOLLY PETERSON: I’m thinking about how, in California, we call people vulnerable, when they might get COVID more often than other people or when they might have to evacuate from a fire. And the risk that they face is so great.

But, actually, what I’ve seen is the way that the systems are vulnerable. The systems that we have for taking care of people, and taking care of their health towards the end of life, seem broken. We’ve actually put people in charge of these homes to take care of people and protect them in a pandemic and in a wildfire. And how we handle that obligation going forward, I think, is something we’re not gonna stop paying attention to.

CELIA LLOPIS-JEPSEN: Yeah, I think we’ll have a better idea of whether this will solve some issues long-term when we see even some of the issues we’re dealing with now being solved because, yes, we’re paying more attention to nursing homes now. But we’re not effectively solving the problems yet that they’re dealing with. So the problem isn’t solved.

On paper it may say that this testing is going to happen. But I’m looking at nursing homes that are scrambling trying to figure out how the heck they’re gonna do it. And I’m still seeing so many problems that aren’t actually being solved yet. So I’m a little hesitant to say that things are gonna be fantastic after this.

KATIE FEATHER: Molly Peterson is a science and environmental reporter for KQED in San Francisco, California. She’s based in Los Angeles.

Celia Llopis-Jepsen is a health reporter for the Kansas News Service.

When we come back, we take a look at what’s keeping long-term care facilities from succeeding and what, if anything, might change after the pandemic.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. We’re talking this hour about the state of nursing-home care in the US. Long before the coronavirus infected people in these facilities, cracks in the long-term care system were already weakening. Producer Katie Feather is back with that story.

KATIE FEATHER: The coronavirus has turned the nation’s attention to many of the issues with nursing-home care. But those issues long-preceded the virus. The question now is, can we emerge on the other side of this pandemic with a system that provides better care for older and disabled Americans?

Joining me to offer insight into that question and more are my guests. Robert Applebaum is a professor of gerontology and director of the Ohio Long-term Care Project with the Scripps Gerontology Center at Miami University in Ohio.

Sonya Barsness is a gerontologist and industry consultant based in Washington DC.

Welcome to Science Friday.

ROBERT APPLEBAUM: Thanks.

SONYA BARSNESS: Thank you.

KATIE FEATHER: I want to start our conversation today by asking you both to give a grade to our current system of nursing-home care. Sonya, let’s start with you.

SONYA BARSNESS: That’s a great question. I would have to break it down into, I guess, different aspects. I would say the people that work in nursing-homes, I would say, are solid– probably A, you know, B-plus, in the sense that I think they work incredibly hard in a very difficult system.

I think the system is probably a D, maybe even an F sometimes, because I don’t think it really is working for either the people that work in it or live in it.

ROBERT APPLEBAUM: Yeah, I think that’s really a good way to think about it. There are many, many dedicated folks who are working in the nursing-home industry. But you really have to go back to this structure.

We don’t really want to pay for serving people in nursing-homes. And, in fact, people don’t want to pay themselves. And people don’t really think about the fact that, someday, they might experience a severe disability. And so most of us don’t save for long-term care. We don’t have private insurance.

And then it leaves society, through the Medicaid program, to essentially pay. And states don’t really want to spend a lot of money on Medicaid. So we have a system that really is not very well thought through. And so, even though we have good people in many cases, the structure just is not set up well to actually provide high-quality care.

KATIE FEATHER: So who are the people in this nursing-home setting? Who are we talking about here?

ROBERT APPLEBAUM: Nursing homes really serve two very distinct populations. And, over the last 20 years, nursing-homes have changed dramatically. So, for example, today a lot of people who use nursing-homes are there for very short periods of time. And they’re basically there to receive rehabilitation, following a hospital stay.

We did a study in Ohio where we followed everybody who went into a nursing-home. And after three months, of everybody who walked through the door, only 16% of those people were still there. And most of them had gone home.

Today, for many people, nursing-homes are what hospitals used to do. And they’re providing short-term rehabilitation. So, for that segment, it’s not the old nursing-home that we would think of. And then, for some people who do stay longer, and typically these days those folks mostly have cognitive impairment or some type of dementia, they’re long-stayers.

So I think the nursing homes are really– do very different things for different people.

KATIE FEATHER: Sonya, you’re a consultant for this industry. I’m curious about, when facilities reach out to you for help, what are they struggling with? And what are they looking for?

SONYA BARSNESS: I think there is a wide variety of reasons. I think, for the most part, the type of work that I do, which is trying to apply a different paradigm of how we can support people in nursing-homes– these are organizations that are looking to do better.

They want to change nursing-homes from an institutional medically-driven culture to one that is based on person-centered values. So I think there is a segment of people that certainly are looking just to do better, to change the way they do things, recognizing that there is a different way.

KATIE FEATHER: You mentioned this person-centered mode of care. That makes a lot of sense. I would assume that institutions would do that, if they were capable of doing that. So what is keeping these institutions from offering this level of care? What are some of those obstacles?

SONYA BARSNESS: There are many reasons why, I would say, nursing-homes may be hesitant or discouraged to change to a person-centered culture. One is just, simply, I think that this is a culture– this institutional culture it has been so pervasive. The roots of nursing-homes are in an institutional medical model.

So undoing that over the years has been a challenging process. It’s inherent in the policies. It’s somewhat inherent in regulations, the reimbursement system, et cetera. So it’s undoing and unlearning a system that has essentially been built over years. And so I think that change in thinking, to me, is sometimes the biggest barrier.

Then there are the logistics of how to do it. But that change process is very difficult because it’s very deep. And it affects literally every single person working in that organization. So it does require an entire organization to be committed to change and to perhaps have guidance on how to do that and to have the– not just the passion but maybe the tools and resources to be able to do that.

KATIE FEATHER: Bob, I want to turn to you because you do trainings with nursing-home administrators. And I want to hear from you what wisdom you’re imparting to them and what you hear from them about these new models of care.

ROBERT APPLEBAUM: One of the biggest challenges that we face is, from a societal perspective, we are most concerned with safety and making sure that frail, older people are being taken care of. And the problem is that, when you focus so much on safety, and of course we all want to be safe, but life doesn’t stop when we have frailty or disability. And we think that it does. And so we tell administrators, and we tell staff, don’t let people fail. Don’t let people be unsafe.

And so we’re not very consistent with our messages. And it’s a very challenging time to be an administrator because the funding is a challenge, the staff is a challenge. We’ve just finished a study where we found that the retention rate for nurse aides in Ohio facilities was around 60%. So that means, after a year, you’ve got a whole bunch of staff that aren’t there anymore. And, if you’re doing very personal kinds of things with people and you have different people coming in, that makes quality difficult.

SONYA BARSNESS: You know, related to your comments on autonomy, I think what’s been really interesting with COVID is that I think this tension that we’ve always had in long-term care, between autonomy and risk, is really being brought up to light. There’s a greater focus on risk because of the virus and the need for them not to have visitors to go outside to participate in group activities.

And so I do really feel like that this is an opportunity, with this virus, for us to unpack this and to look at how we can do a better job at leading with autonomy rather than leading with risk.

KATIE FEATHER: Yeah, and some of the perennial problems with nursing homes, even before COVID, have to do with staffing and funding. What are nursing-homes doing right in terms of staffing and keeping retention-rate high? What have you seen in your research?

ROBERT APPLEBAUM: So my colleagues at the Scripps Gerontology Center did a study a few years ago, where we identified the best-performing facilities in the state in terms of having high retention rates. And we went out and visited them.

And what we found was that, yes, economic conditions and benefits and those kinds of things are important. But we also found that the facilities that were the best in the state were able to demonstrate to staff that they cared. You know, this set of the employment population are folks who are low paid, they have relatively low education. They have many challenges that low income workers face. Their cars break down, they get evicted.

And what these facilities did, what these administrators did, was they were able to communicate that they had their back. And so they would help them fix their car. They would help them find a place to live. And, for those folks, they knew that the administrator cared. And, when it came time to thinking about leaving to go to a different job, they didn’t go.

So one of the things we see is this is a place where management matters. And yes the structure of the industry is a challenge. But management also matters.

KATIE FEATHER: So I want to take the opportunity here to talk about possible reforms, ways we can improve this system, one of them being maybe we walk away from this model of nursing home care altogether.

A lot of the conversation around elder-care in the United States right now is focused on aging at home and providing more support for that. Sonya, do you think that one solution to all this is just to walk away from this model?

SONYA BARSNESS: You know, it’s my belief that we will always need some sort of nursing-home level of care, meaning care for people with complex medical needs, complex chronic conditions, and particularly care and support for people living with dementia.

However, I do think that what has to exist is not what we see now, in terms of the model of nursing-home. What I would love to see is, rather than us talking about aging-in-place as something separate, whatever we develop that is like a nursing-home that is senior living is integrated into communities. So that it’s not separate.

ROBERT APPLEBAUM: If I could jump in to say that the shift to home and community-based services really has happened. I think the question now is how do we do things differently? You know, a physician named Bill Thomas many years ago began to– he was working in a nursing home and he said, wow, these are sterile environments. And we need to make this a place where people live.

And he brought in pets and plants. And, after a few years of doing that, he decided– Dr. Thomas decided that just isn’t gonna be enough change. And so he created something called the greenhouse or the small house, where people would be living in groups of 10 and they would be living together. And that’s been a reform attempt. And there are others, as well.

But the fact of the matter is it’s very difficult. The average nursing-home in America is about 100 people. Some much bigger than that. And it’s very difficult, in that institutional setting particularly when it’s doing many things, to make it a home-like environment that we all want to be living in.

KATIE FEATHER: I’m Katie Feather. And this is Science Friday from WNYC Studios.

I’m talking about nursing-home reform with my guests, Robert Applebaum, professor of gerontology and director of the Ohio Long-term Care Project with the Scripps Gerontology Center at Miami University, Sonja Barsness, a gerontologist and industry consultant based in Washington DC.

So what I hear you both saying is that we don’t really think about needing this type of care. We don’t plan for it until it’s too late. But the pandemic has really directed the nation’s attention in a focused way to this system. Do you think that maybe that will provide the momentum to create change after this?

ROBERT APPLEBAUM: You know, to some extent I think that’s exactly right. You know, if you look at most states, you’re talking about– 40% to 50% of the deaths in a particular state are from COVID, are people in nursing homes.

So they certainly have got a lot of attention. And people are wondering. But I think the challenge is that the attention is much more regulatory and safety-focused. And we’re gonna need to shift our attention to– this is where people live and this is the life they kind of live. So I think it can shift attention. But the question is, how is it going to shift attention? And can we shift in a way to think about what’s the best way to live with a disability and what’s the best setting to do that?

SONYA BARSNESS: And I’ll add to that, too, is that, I think, one way that we have to move forward with change is by not just giving new money or additional money to the existing system as it is. I think that we do need a total redesign. And that hopefully will include more reimbursement, more money, and more focus. But, to just continue to use the same system but throw money at it, is really not going to help, in terms of a redesign.

One of the things that has also come out of the pandemic is an incredible advocacy movement of family members, of people living on long-term care that have been advocating for the voices and the rights of their loved ones living on long-term care to ensure their safety, to ensure their ability to be socially-connected with others outside their communities.

KATIE FEATHER: I’m so glad you said that, Sonya, because I want to end by saying that we had a lot of Science Friday listeners call in to share their mostly-negative experiences with nursing-home care for their loved ones. And, until we have a very high standard and very high level of care at all facilities across the country, I want to ask, what can these folks do if you’re having to face the difficult decision of putting a loved one in a nursing-home?

What are the questions that they should be asking? Where should they be turning to for good information about how that nursing-home is treating its residents? Are there any tools that these families can use before they make that decision?

SONYA BARSNESS: The Pioneer Network actually has several really good tools for families, that are key questions to ask. And I feel like these questions are a little bit unique than some of the other questions out there because they prompt a family member, or a person looking to live in long-term care, to look at things like, do people welcome you when you walk in the building? Do they look at you in the eye? Are people smiling, as well as things like, are the people that work there consistently assigned, meaning that the same people work with the same residents?

Existing tools like Nursing Home Compare, from the Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services, that provide clinical information about nursing homes, readings, all sorts of great data. And I would say just talking to people in your community and talking to the people that live in these nursing-homes and assisted-living communities that you’re considering to get a sense of what life is like there.

ROBERT APPLEBAUM: Yeah, and I guess I would say, once somebody is in a facility, I can’t emphasize enough how important it is to have a presence in that facility, to visit and to know staff, and to be able to support both staff and the family member living in the facility. And having a family presence is always gonna be critical.

There are a lot of caring workers. But we’ve got structural issues that need to be addressed in order to have us be satisfied with the quality of care we’re gonna have in this country.

KATIE FEATHER: All right, we have to leave it there. But thank you so much, both of you, for joining us.

Robert Applebaum is director of the Long-term Care Project at Scripps Gerontology Center at Miami University in Ohio.

Sonya Barsness is a gerontologist and industry consultant based in Washington DC. Thank you guys for joining us.

ROBERT APPLEBAUM: Our pleasure.

SONYA BARSNESS: Thank you.

KATIE FEATHER: For Science Friday, I’m Katie Feather.

IRA FLATOW: And you can read more of our coverage of nursing-home care and hear stories from our listeners on our website at sciencefriday.com/nursinghome.

Copyright © 2020 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.