Seeing The History Of Filipinos In Nursing

15:47 minutes

You may have seen a grim statistic earlier this year: 32% of U.S. registered nurses who died of COVID-19 by September 2020 were of Filipino descent, even though they only make up 4% of nurses in the United States. Yet an event like the pandemic is disproportionately likely to affect Filipino-American families: Approximately a quarter of working Filipino-Americans are frontline healthcare workers.

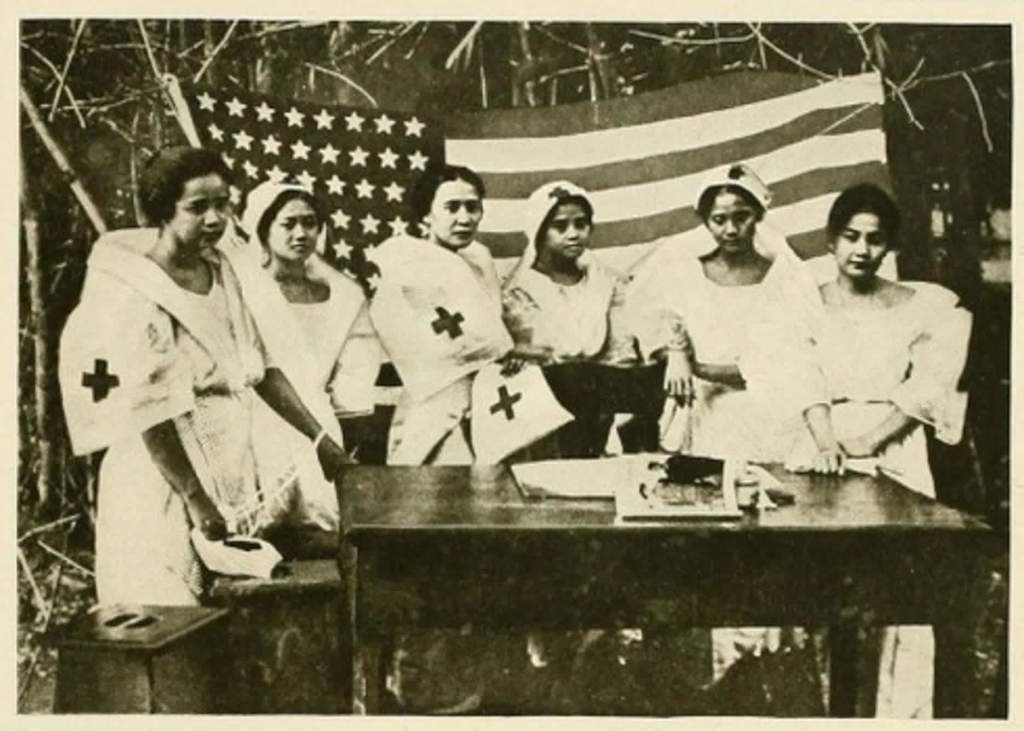

There’s a deep history of Filipino immigrants and their descendants in frontline healthcare work. This Filipino-American History Month, Ira talks to nurse and photojournalist Rosem Morton and freelance journalist Fruhlein Econar about their recent collaboration for CNN Digital, using photographs from Morton’s National Geographic-supported “Diaspora on the Frontlines” project.

They talk about the long reliance of the U.S. healthcare system on the Philippines, and the importance of documenting the lives, not just the disproportionate hardship, of these frontline healthcare workers and their families.

We asked for stories from Filipino-Americans who work or have worked as nurses. Here is some of what they shared with us.

Jona C. from New York

The day I saw my co-worker deteriorate during the day while I was working with her, I knew she had COVID-19 and therefore I was exposed as well…I was not asked to be quarantined for being exposed (to COVID-19)…I developed rashes for 5 days after I [was exposed]. I was having similar symptoms as my pediatric patients who were having multisystem inflammatory syndrome and required more aggressive treatments to survive…I did not have respiratory symptoms, but I feel to this day that I’m not the same and sharp after COVID-19.

I am still grateful to my five friends, who are also nurses and bravely came to my house to eat together and just bond. Later on, we used dancing as an exercise and formed a new organization to help other nurses in our area. This pandemic was brutal but those who survived appreciated life better and realized that no human is an island and humans are truly social beings.

Christian F. from New York

My Filipina single mother is a registered nurse herself of thirty years so her profession definitely left a mark on me growing up. I arrived to the United States from the Philippines when I was six-years-old and I saw early on the love that my mother had for her career. Despite how exhausted she evidently was after every 12-hour shift, she always seemed to look forward to the next shift. Her zealousness in her service towards the sick inspired me to also take up a path of service some day.

To this day, becoming a nurse has been one of the best decisions of my life so far. I have personally seen the power of nursing care in the lives of others…I remember that one night when ten of our patients died within three hours. I remember all the hands that held my hand as they took their last breath. I remember setting up video calling programs to allow family members to speak to their dying loved one for the last time. I remember not knowing what to do, or what to feel, or what to think. I remember thinking everything that we were doing was useless. I remember not being able to sleep for nights because all I could hear and see were the cries of families and the last tears that fell down my patients’ faces. I remember being afraid. I remember wanting to give up.

I remember. Those are the two words that encompass my life during the COVID-19 pandemic. All I can do is remember, but also to try not to. Visions of memories that will forever remain in my heart and mind. We truly have come a long way, and it has been beyond an honor and a privilege to be a part of that service.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Rosem Morton is a nurse and photojournalist of Diaspora on the Frontlines. She is based in Baltimore, Maryland.

Fruhelin Chrys Econar is a freelance photo editor based in Kansas City, Missouri.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. When my aging mother entered a retirement home, I met my first Filipino nurse. And through the years of her care, I would meet many, many more and would learn how Filipino nurses were sort of hiding in plain sight. I mean, they shouldered so much of the health care burden, but unless you were immersed in the health care industry, you would hardly know. Like I didn’t.

I bring this up because October is Filipino American History Month. It’s a recognition of both the long history and large presence of Filipino immigrants and their descendants in the US. Here’s some history 101 for you. The Philippines had a colonial relationship with the US beginning in 1898, when the US made the Philippines a territory. The formal relationship ended with the independence of the Philippines in 1946. But Filipinos have continued to emigrate in large numbers to the US. In that time, Filipino Americans have become the second largest group of Asian-Americans in the US. And one in four Filipino Americans in the US is a frontline health care worker.

JOLLENE LEVID: It’s like, from the security guards to patient transport to the janitors, the LVNs, CNAs, cafeteria workers, nurses and doctors, you’ll see Filipinos.

IRA FLATOW: That’s Jollene Levid, the daughter of one such nurse. WNYC’s podcast, The Experiment, talked to her and her mother, Nora, in February, in a story about a group of nurses who emigrated from the Philippines 40 years ago. But it’s also the story of another statistic. Of the registered nurses who died in the first nine months of the pandemic, nearly a third were of Filipino descent.

NORA LEVID: We knew it’s going to get worse. In fact, I remembered when I was in ICU, somebody call in sick. And we have this joke saying, “Oh, you cannot call in sick. Not unless you’re dead.”

IRA FLATOW: Joining us next are two Filipino journalists who shared a photo essay about Filipino nurses and their families on the frontlines of the pandemic for CNN Digital. Rosem Morton, she’s a nurse and photojournalist based in Baltimore, Maryland. She’s been documenting the lives of nurses and their families in a photography project called Diaspora on the Frontlines. And for Fruhlein Econar, a freelance photo editor for CNN Digital based in Kansas City, Missouri. We have a link to their work on our website, sciencefriday.com/nurses. Welcome to Science Friday.

FRUHLEIN ECONAR: Hello.

ROSEM MORTON: Thank you so much for having us.

IRA FLATOW: You’re very welcome. Thank you for taking time to be with us today. I just shared a personal story of mine about my mother, and I said in the intro that I didn’t realize there was such a deep, decades long history of Filipino Americans and immigrants in health care. How did this come about?

FRUHLEIN ECONAR: Yeah, you know, that’s totally not uncommon. Because even for me, I only recently really started looking into this history. And I was surprised at what I found as well. And so, I grew up learning English. My mom immigrated to the US a few years ago, but I’ve been in and out of the country my entire life. And I never really understood why. And I never understood the historical forces behind that.

And as I was looking into this history, I found that during the US’s 48th year rule, it really, it exported its language, its values, and its culture to the Philippines that inadvertently primed us to assimilate well within the American workforce, which also explains why there are so many Filipinos in the US. But at the same time, in 1898 the US was growing into a superpower, and thus began this narrative that America was a place where Filipinos could go and prosper not knowing what awaited them on the other side. And so there were a number of factors and policies that work together to foster this culture of migration.

There is the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and further immigration acts after that, like in 1917 and 1924. They barred a number of Asian immigrants from entering, except the Philippines, because we were a colony. So when there was a shortage of farm workers, Filipinos answered the call. And then there are a number of Filipino veterans who fought in World War II for the US. Those veterans became US citizens, and then their family members chain migrated as well.

And then, of course, most pertinent to this story, there is the nursing migration that happened in the 1960s following World War II through the Exchange Visitor Program, which Catherine Ceniza Choy, she wrote a really great book that synthesized a lot of this from a health care perspective.

And so there’s a lot of cultural familiarity already on the Philippines’s side towards the US, definitely not necessarily the other way around. Because they implanted a number of their institutions, our public school system, that’s where we learned English, to our universities and then the aforementioned nursing programs. American businesses also set up shop in the country and many of those firms still operate as large players to this day. And so there are a number of pathways that diverge to answer the question of why there are so many Filipinos in the US, and what that history looks like.

IRA FLATOW: That’s very interesting. Rosem, can you fill us in more about the health care industry specifically?

ROSEM MORTON: In 1948, the Philippines and the US entered into an agreement to finance binational centers to coordinate educational exchange programs in a variety of fields, and this included health care. This started the large migration of Filipino nurses to America. And by the 1960s, the demand increased dramatically following the passage of Medicare and Medicaid, and also spikes in illnesses such as the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s. So that all influenced the chain migration of Filipinos. And also on the other side, there were also a lot of events happening in the Philippines that was destabilizing, that people really wanted opportunities outside of their home country.

IRA FLATOW: Why did the US have such a demand for nurses from overseas?

ROSEM MORTON: It happened after World War II when American women really did not want to work in health care roles. So the US tried to fill in the shortage with nurses abroad.

IRA FLATOW: And so they were recruited?

ROSEM MORTON: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: And they– that is continuing even now

ROSEM MORTON: Yes, definitely continuing till now.

IRA FLATOW: And are they being paid fair wages and fair housing and things like that? Or are they being exploited?

ROSEM MORTON: I think it’s hard to speak about it because nobody is really willing to officially go on the record that there is exploitation happening. But I am aware that many of the nurses who have been recruited here have to fulfill a certain number of hours in their contract. And within those hours, a large part of their salary is being taken away. And sometimes being seen as a foreign worker, or someone through an agency as a nurse, there are a lot of assumptions with that. And sometimes you are also given much more difficult work, much more difficult shifts, and things like that.

IRA FLATOW: Rosem, you tell a story of Jennifer Bulaong at the beginning of the pandemic. She was in a hospital in Missouri trying to fulfill the requirements of a contract she had, like you say, while waiting to join her family in Maryland. How often are family separated like this?

ROSEM MORTON: Too often to count unfortunately, yeah. For example, the Bulaong family. The mother of their family, Leane Bulaong, she has worked abroad for about 12 years now. And on and off those 12 years, she has been with parts of her family and not her complete family. So this year, when Jennifer finished her contract, is really the first time they’ve all really been together in one area for roughly 12 years. And like we’ve mentioned earlier, this is a very common experience for Filipino health care worker families and just generally Filipino immigrants.

And I can speak for myself as well. My mother had migrated here about three years ahead of me, and she is a special education teacher. And she was also recruited from the Philippines.

IRA FLATOW: What has the pandemic then meant for families like the Bulaongs?

ROSEM MORTON: I think the pandemic really separated a lot of families. So for example, for the Bulaongs, Jennifer was supposed to visit her family for the holidays. But her mother Leane, her father Jim, and her other sister Jill, they all got sick with COVID-19. So they were really apart for the holidays. And for other nursing families who have families in the Philippines, family members in the Philippines who are sick and dying, it’s something that they couldn’t visit their family member’s home. And now there is a roughly a 10 day quarantine for Americans, or people from America, to visit the Philippines. So it’s been a huge deterrent for Filipinos to visit their family. So many, many families have been separated for over a year and a half now.

IRA FLATOW: And the Bulaongs have more than one nurse in the family, I understand. This is also common for Filipino American health care workers. They’re not the only ones in the household, right?

ROSEM MORTON: Yes, definitely. They– Leane Bulaong is a nurse. Jennifer Bulaong is a nurse. Her, Leane’s husband, Jim, is in nursing school. And Leane’s other daughter, Jill, is also in nursing school. And that’s also something that we really touch upon in this photo essay is that there are many– usually many nurses in the family are many health care workers in a family, and it also increases the risk for this community to really be exposed to the virus.

IRA FLATOW: You know, we really can’t show photos on the radio. We would love to show photos. Can you describe for us what kind of images from this essay would you want people to remember? Fruhlein?

FRUHLEIN ECONAR: It’s really important to see these families exist outside of their workplace. There’s already this existing association between like Filipinos and health care workers, but they live lives beyond that. And that’s really something that we wanted to touch on is that they are partners, they’re parents, siblings. I think it’s just this normalizing of their faces beyond a health care setting.

IRA FLATOW: We have your photo essay, a few pieces in the New York Times and ProPublica, a new documentary series on PBS. All that being said, it’s interesting to me that during this pandemic where we’ve talked so much about health care workers, nurses and doctors, and staffing crises, and physical danger. Yet so little has been said about the Filipino American community specifically, until what, the last few months. Has that started to change as far as you have both seen? Rosem, let me begin with you.

ROSEM MORTON: I think it’s starting to change. But at the same time, I am really the only person who has done long term work within this community. So in some ways I have monopolized these stories with these nine people. And even if this is representing this diaspora of Filipino nurses, I don’t want these nine stories to be the only stories representing this large diaspora. And so yeah, I think it is changing, and we are talking about Filipino nurses more. But there is definitely room to improve, for us to really diversify our knowledge of this community.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. Going back to the front line nature of being a nurse right now, I mentioned that the pandemic has had a huge toll on Filipino families. 32% of nurses. Is there something that you hope changes for these families, and is there a way for that to change?

FRUHLEIN ECONAR: That’s a hard question for me to answer, honestly. One of the more interesting stats that I came across as I was reporting this story is that not only are Filipinos more likely to be in a position to be exposed to COVID, it’s also that Filipinos were three times more likely to have hypertension and two times more likely to have diabetes. Both of which are risk factors for severe COVID-19 compared to white individuals in California. This is a stat from the JAMA Network Report. And so it’s a number of things piling together that make this community particularly vulnerable to COVID. So I don’t know how to answer that.

IRA FLATOW: I think that one question this all seems to beg is that you’ve seen that nurses in general are traumatized. They’re burned out. They’re quitting in large numbers, as we’ve seen so much reporting on. Will the US health care system continue to rely on nurses and doctors from overseas to fill out the burnout?

ROSEM MORTON: Yes. I definitely can see that this is happening. I attended an event a couple of months ago. And one of the doctors told me that he works in Florida, and he said their hospital had already gotten hundreds of Filipino nurses to fill in all of the shortages of their hospital. So I believe that this mass migration will continue on. Yes.

IRA FLATOW: And my last question to you would be, are there really still good stories out there waiting to be told about Filipino Americans on the front lines, and will somebody be telling them?

FRUHLEIN ECONAR: I hope so, you know? The same way that Filipinos are not a monolith. There are many other kinds of experiences that, as storytellers you come from a certain place. And we hope that somebody else with a different background will be able to see another angle of the story. And ultimately, what I really enjoyed about working on this story, and potentially other stories about the Filipino experience in the US, is just putting these things on record and making the case that we were foundational to the creation of this country, whatever it looks like right now. And it’s not just, it’s not a purely transactional thing. There’s also a lot of– I think that Filipinos can take a lot of ownership over what they see of America right now.

IRA FLATOW: That’s a good place to end and a good thought to end on. I want to thank both of you for taking time to be with us today Rosem Morton, a nurse and photojournalist based in Baltimore, Maryland. She’s been documenting the lives of nurses and their families. And Fruhlein Econar, a freelance photo editor for CNN Digital based in Kansas City, Missouri. We have a link to their work on our website, sciencefriday.com/nurses.

Copyright © 2021 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

A selection of Science Friday’s podcasts, teaching guides, and other resources are available in the LabXchange library, a free global science classroom open to every curious mind.

A selection of Science Friday’s podcasts, teaching guides, and other resources are available in the LabXchange library, a free global science classroom open to every curious mind.

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.

Kyle Marian Viterbo is a community manager at Science Friday. She loves sharing hilarious stories about human evolution, hidden museum collections, and the many ways Indiana Jones is a terrible archaeologist.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.