Indigenous-Led Biology, Designed For Native Communities

17:11 minutes

Monday was Indigenous Peoples’ Day here in the United States: a holiday to honor Native Americans and their resilience over many centuries of colonialism. Due to a long history of discrimination, Native Americans face stark health disparities, compared to other American populations. Illnesses like chronic liver disease, diabetes, and respiratory diseases are much more common in Native communities.

This is where the Native BioData Consortium (NBDC) comes in. It’s a biobank, a large collection of biological samples for research purposes. What sets this facility apart from others is its purpose—the biological samples are from indigenous people, and the research is led by indigenous scientists.

This is important, say the founders, because for too long, biological samples from Native people have been used for purposes that don’t benefit them.

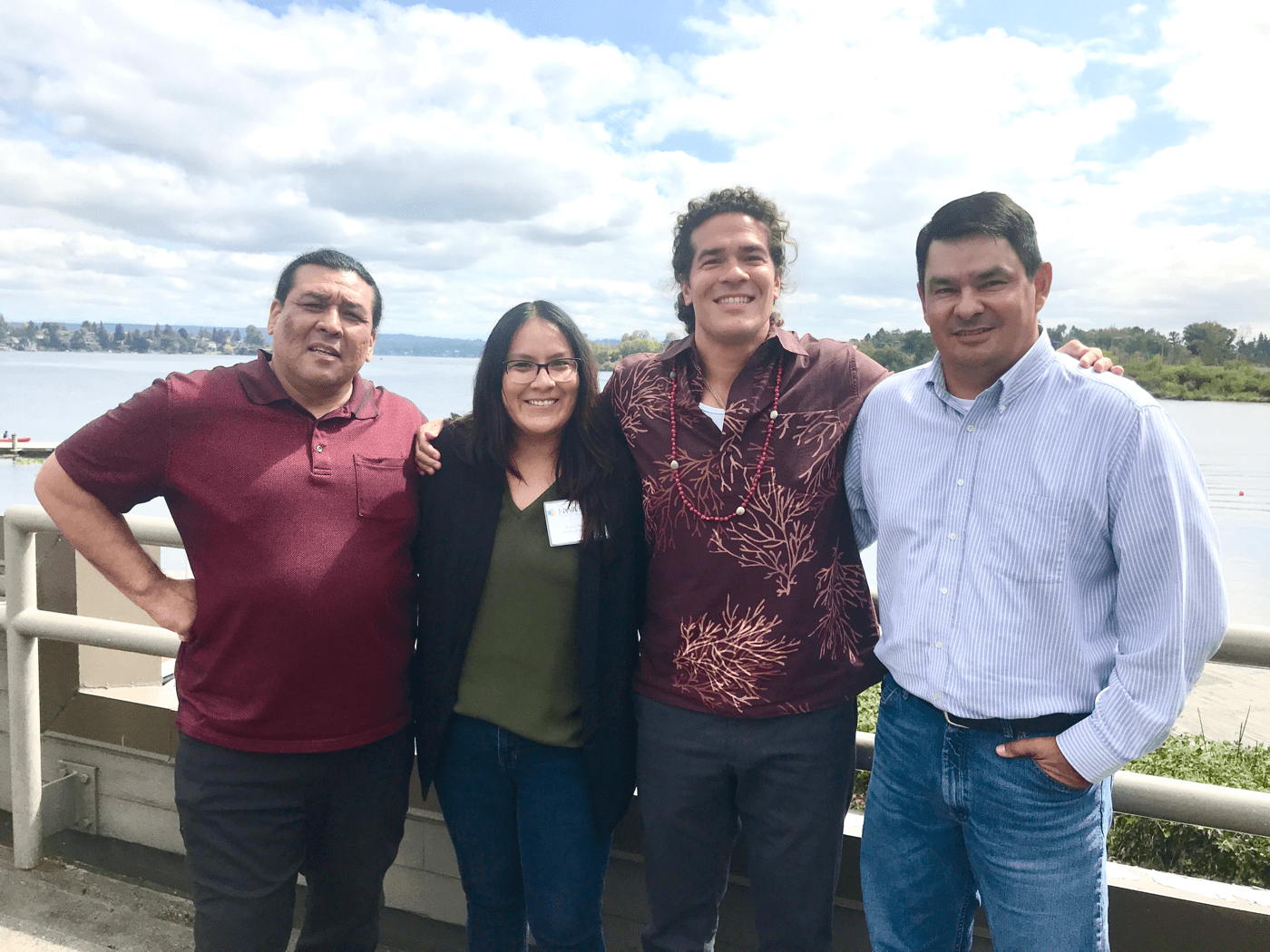

Joining Ira to talk about the importance of having a biobank run by indigenous scientists are three foundational members of the project: Krystal Tsosie, co-founder and ethics and policy director of the NBDC and PhD candidate in genetics at Vanderbilt University, Joseph Yracheta, executive director and laboratory manager of the NCDC, and Matt Anderson, assistant professor of microbiology at Ohio State University and NCDC board member.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Dr. Krystal Tsosie is co-founder of the Native BioData Consortium and an assistant professor and geneticist-bioethicist at Arizona State University. She’s also a member of Navajo Nation based in Tempe, Arizona.

Joseph Yracheta is Vice President and Laboratory Manager for the Native BioData Consortium in Eagle Butte, South Dakota.

Matt Anderson is an assistant professor of Microbiology at Ohio State University in Columbus, Ohio.

IRA FLATOW: This is “Science Friday.” I’m Ira Flatow. Last Monday was Indigenous Peoples’ Day here in the US, a holiday to honor Native Americans and their resilience over many centuries of colonialism. Because of a long history of maltreatment and discrimination, Native Americans’ health disparities are stark compared to other American populations. Illnesses like chronic liver disease, diabetes, and respiratory diseases are much more common.

This is where the Native BioData Consortium comes in. It’s a biobank, a large collection of biological samples for research purposes. But what sets this facility apart from others is its purpose. The biological samples are from Indigenous people and the research is led by Indigenous scientists. Joining me now are three of the scientists involved in this work.

Krystal Tsosie, co-founder and ethics and policy director of the Native BioData Consortium, PhD candidate in genetics at Vanderbilt University. She’s based in Phoenix, Arizona.

Joseph Yracheta, executive director and laboratory manager, the Native BioData Consortium. He’s based in Eagle Butte, South Dakota.

And Dr. Matt Anderson, assistant professor of microbiology at Ohio State University, board member and treasurer of the Native BioData Consortium. Based in Columbus, Ohio.

Welcome, all of you, to “Science Friday.”

MATT ANDERSON: Thank you for having us.

JOSEPH YRACHETA: Thank you.

KRYSTAL TSOSIE: Thanks for having us.

IRA FLATOW: You’re all welcome. Krystal, talk me through the importance of having a biobank run by Indigenous scientists for the benefit of Indigenous people.

KRYSTAL TSOSIE: So, for the first time, really in history, we have a cohort, a wealth of Indigenous expertise in precision health and genomics, for the first time. And it’s really great that we’ve been able to get these great minds together to help co-lead and found this organization. For too long in the status of biomedical history, data has been usurped from Indigenous peoples and often not to our benefit. So being able to have community members, tribal leaders, and scientists like us who come from the communities themselves to be able to advocate for how this data is collected and used, is really important, especially if we’re going to be talking about, not just racial justice, but also genomic equity and data equity.

IRA FLATOW: Krystal, why do you think there’s been such a lack of scientific research to benefit Native populations?

KRYSTAL TSOSIE: If you think about how scientists have entered Indigenous communities, oftentimes it has been for this very grand scheme of– one day, some point down the line, your data, Indigenous peoples, may benefit you. And this is actually the promise that a lot of scientists, particularly in the mid-’90s and early 2000s, did for, particularly, Indigenous peoples in Central and South America. They entered our remote communities, took our blood, promised us medicines, and then they disappeared.

There’s actually a New York Times article in which a reporter from the New York Times came back to the Cruciana, they reside in Central Amazonia, and asked them, did they actually deliver on the promises? Where are the medicines? And the Indigenous peoples angrily stated, no. But Coriell Cell Repositories had been selling their blood and access to the genomic information.

And I talked to a lot of scientists, and I asked them, are we perhaps overpromising on what precision health can deliver, right here and right now. And scientists, some of them, worryingly state, well that’s not our problem. Our focus right now is the research. Maybe somewhere down the line it might translate into some benefits for the community. And unfortunately, for Indigenous peoples, we’re dying at disproportionate numbers now. We cannot wait.

IRA FLATOW: Joseph, do you have some of the same fears and concerns about data being accessed by outside parties?

JOSEPH YRACHETA: Yeah so because of the settlor colonial borders often Native people who share ancestry are thought of as separate and separate legal jurisdictions and separate exposures, and that part is true. But where we do have similarity is people’s interest in the genetic part, and not so much interest in the health improvement part. And so they can go over the border into Mexico, Central America, South America, where those native people do not have sovereignty or any kind of protection, and get what they want and still avoid the health improvement part.

IRA FLATOW: When you say the genetic part, what do you mean by that?

JOSEPH YRACHETA: So, you’re seeing some of these instances recently in isolated populations where they find different resistance to disease because of genetic variants. We saw that with HIV in the Scandinavian countries, where about 8% of the population was resistant to HIV because they have a cholesterol variant to prevent the virus from getting into the cells. So big data and big pharma companies are looking for those types of genetic gifts, treasures– whatever you want to call them– to basically help the whole world with health crises. But often, at least the Indigenous context, the benefits from that type of research won’t come very quickly to these communities because of cost and other political issues. And so those are the kinds of genetic treasures that people are looking for.

IRA FLATOW: I want to bring Matt into the discussion. Matt, I know you’re a microbiologist. How does microbiology fit into the work of the Native BioData Consortium?

MATT ANDERSON: Sure. So when we’re talking about microbiology contexts, oftentimes we center that on the individual, the human, the host side. And so you’ve heard the microbiome being called things like, an essential human organ that contributes to overall health and disease states. And that’s been shown to be true in a number of cases.

So in thinking about performing microbial work, we need to be incorporating the host context and the implications on not just the microbes, but the human as well. So within Indigenous communities, the relationship or the viewing of our relationships with different pieces of our environment are going to be a little bit different. And microbes need to be considered not just as these organisms that we’re not able to see that can potentially cause disease and live with us, but they’re really– we live in relationship with them. They determine our health and we impact their community structure, their health.

So within a microbiology context, when you’re working on microbiome, you’re working with different bacterial samples, archaea, fungi, et cetera. The relationship here that’s presented itself between the microbes and you as the individual changes. So the approach that needs to be taken when performing microbiome studies, in particular with Indigenous people, is going to look different than it does when working within US general populations. There’s going to be this understanding of relationality that often doesn’t occur within a clinical setting as you’re taking samples from patients.

IRA FLATOW: Can you explain that a bit more– why the microbiome of Indigenous peoples will look different than non-indigenous peoples?

MATT ANDERSON: Sure. So the difference in the appearance of that microbiome is really revolving around that relationality. So the obligations that we have to all the pieces of our environment, including microbial systems that live within our guts on our skin, we have an obligation to help maintain and protect those organisms because of their exact same role that they have in relationality to us and protecting us as well. So it’s more a human-centered approach as to thinking about that relationship between the microbes and the human, and how that balance is fundamentally what’s going to be important in promoting health of the individual, as well as health of the microbiome itself.

IRA FLATOW: Would you extend that comparison, also, to the microbiome in the soil? I mean, there’s a huge microbiome in the soil. Do you study that also?

MATT ANDERSON: So we have some new projects that have popped up, specifically around microbiome in the soil. And this is being done on Cheyenne River based on land usage practices. Based on the way that humans are interacting with the soil, are we altering things in such a way that it’s going to be detrimental on the microbes that are found there.

And promoting the ecological health of the soil, that promotes not only the ability to be able to use the land for different purposes that people are interested in revolving around agriculture and ranching, but also in the different types of plants that are able to grow based on the microbial community profiles of the soil.

Are those soils now no longer able to support plants that are important for medicine? Plants that are important for ceremony. So how does the human impact present itself, not only the microbial contents, tracing itself back to humans, but also through all the other ecological systems that exist in relationship.

IRA FLATOW: I’m also reminded of a legal case that was made into a play called Informed Consent. And it was a case between the Havasupai Tribe and Arizona State University. The scientists were called in to look at the prevalence of diabetes in the communities and see if there was a genetic disorder there.

And what they wound up doing was, on their own, without informed consent from the tribe, looking– hey, where did this tribe come from, genetically? And they came up with a migration pattern that contradicted traditional stories. And the tribal leaders were very, very upset with this, that they went beyond what they were told to do. Are you familiar with that case?

KRYSTAL TSOSIE: Well, I’m an incoming assistant professor to Arizona State University, which is at the center of that landmark lawsuit. So I’m going to jump in here and perhaps provide a little bit of commentary.

IRA FLATOW: Please.

KRYSTAL TSOSIE: There was, of course, an uproar in that this data was collected from 50% of the Indigenous community members without even having them sign consent forms– which broadly consented to the use of their samples and data for anything that researchers felt, deemed worthy of the greater scientific good, which is a very common template language at the time. But one of the concerns, of course, was the cultural misalignment of scientific purposes and entering communities to perhaps prove a hypothesis, which is culturally incongruent with how the peoples perceive their own cultural origin stories, because the Havasupai Tribe believe that they actually originate at the base of the Grand Canyon.

But there were other concerns, as well. Another concern is that the researchers promised that they were going to investigate type-2 diabetes, but really they were also looking at other stigmatizing conditions like schizophrenia and other mental conditions. And they didn’t inform the community beforehand that they were going to use their samples and data for those purposes.

One of the concerns, too, is that even though this broad consent to the collection of data was the norm in the early 2000s and mid-1990s, when this data collection took place, we’ve actually shifted back to broad consenting today. There was a period of time in which researchers had to get study-specific informed consent. So if there was any change in the research protocol or the research question, then researchers had to go back into communities and re-ask people to sign informed consents again. And scientists found this too logistically burdensome because while scientists are great at collecting data, they’re not necessarily great at– and this is speaking from my own personal experience– they’re not necessarily great at connecting with community members and communicating back. Or at least they weren’t in the mid-to-late 2000s.

And now, in this big-data era that Joe mentioned, we’re now harmonizing data across multiple data sets. And, in order to do that, we’ve again re-entered this era of broad consenting in which we’re asking people to contribute their data, and genomic data, to data sets for time immemorial without having any consent as to what happens to their data in downstream studies.

JOSEPH YRACHETA: So basically, Ira, what it comes down to is respect for Indigenous people. So just, as Krystal mentioned, informed consent versus broad consent has this pendulum-like motion in research, so too does the idea of self-determination for Indigenous people.

So, of course, early in our history with Europeans, it was very much a conquest-type mentality. And then later on it became, they need to have some autonomy and self-determination. And now we’re in the current era, we’re kind of back at that place where people want Natives to assimilate and become part of the broader US fabric.

So that idea of whether or not Indians are wards of the state or whether they’re independent nations is at issue. Researchers, as Krystal pointed out, don’t have this extra layer of public relations comfort. They often defer to the federal rules or federal policies. And, for right now, it’s kind of been this detente where neither side really wants to push the issue because both sides might feel that they would lose some power. So we, as scientists, are operating in this gray area. And in that gray area is where we are really afraid that lots of things are going to get lost in the mix.

IRA FLATOW: Very interesting. Just a quick note that I’m Ira Flatow, and this is “Science Friday” from WNYC Studios. Joseph, the Bayh-Dole Act, that’s an older act, is a federal law that lets universities patent and commercialize what’s discovered by their employees and property. Are there issues with keeping these samples and your results in-house and not commercialized?

JOSEPH YRACHETA: Yeah, it’s another gray area. And again, I think both sides are a little bit wary to push that envelope because the decision might not be what they want. And often people don’t think of science and research as political, but it definitely has become so since the ’40s.

And the Bayh-Dole Act pushed that even further, because a lot of the data that was being generated through public tax dollars didn’t have ownership, so nobody wanted to develop it further. And so that was one of the concessions that Congress made. And a lot of researchers themselves don’t know the higher legal and administrative policies of the university they work in.

And then that was made even further entrenched in law with the America Competes Act from about 2007 to 2014. Many modifications were made there so that even private corporations can use public tax dollars to generate data for such ventures.

Generally, there has been this idea of a need for consultation with tribes, impacting anything that– their lifestyle, their economy, their political and intellectual property rights– that’s been in the books for quite a while. But what hasn’t happened was any kind of consideration in any of these acts for tribes. And right now, the main stakeholder is the universities and we think that it’s high time that tribal groups become recognized as a stakeholder in that data management.

IRA FLATOW: Unfortunately that’s about all the time we have for now. We could spend a lot more time talking about all this. I’d like to thank my guests.

Krystal Tsosie, co-founder and ethics and policy director of the Native BioData Consortium, PhD candidate in genetics at Vanderbilt University. She’s based in Phoenix, Arizona.

Joseph Yracheta, executive director and laboratory manager the Native BioData Consortium. He’s based in Eagle Butte, South Dakota.

Dr. Matt Anderson, assistant professor of microbiology at Ohio State University, board member and treasurer of the Native BioData Consortium. Based in Columbus, Ohio. Thank you all for taking time to be with us today.

MATT ANDERSON: Thank you very much for the time.

KRYSTAL TSOSIE: Thank you.

JOSEPH YRACHETA: Thank you.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

A selection of Science Friday’s podcasts, teaching guides, and other resources are available in the LabXchange library, a free global science classroom open to every curious mind.

A selection of Science Friday’s podcasts, teaching guides, and other resources are available in the LabXchange library, a free global science classroom open to every curious mind.

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.