Fossil Finds Could Mean A Wider ‘Cradle Of Humanity’

16:20 minutes

This week, researchers reported that they think fossils found in North Africa are the remains of Homo sapiens from over 300,000 years ago. If the team is correct, the find represents the oldest known Homo sapiens fossils. The remains, along with some stone tools, were found at a site in Morocco rather than in more southern sites in Ethiopia’s Rift Valley, which has long been associated with early humans.

Shara Bailey, an anthropologist at New York University and one of the authors of a report on the find, published this week in the journal Nature, joins Ira to talk about the fossils and what information they add to the story of early humans. She’ll also talk more broadly about her specialty—the interpretation of ancient dental features, from teeth to jawbones—and what tales teeth can tell anthropologists. Her work is the subject of a new Macroscope video.

Support Science Friday’s short documentaries by becoming a patron.

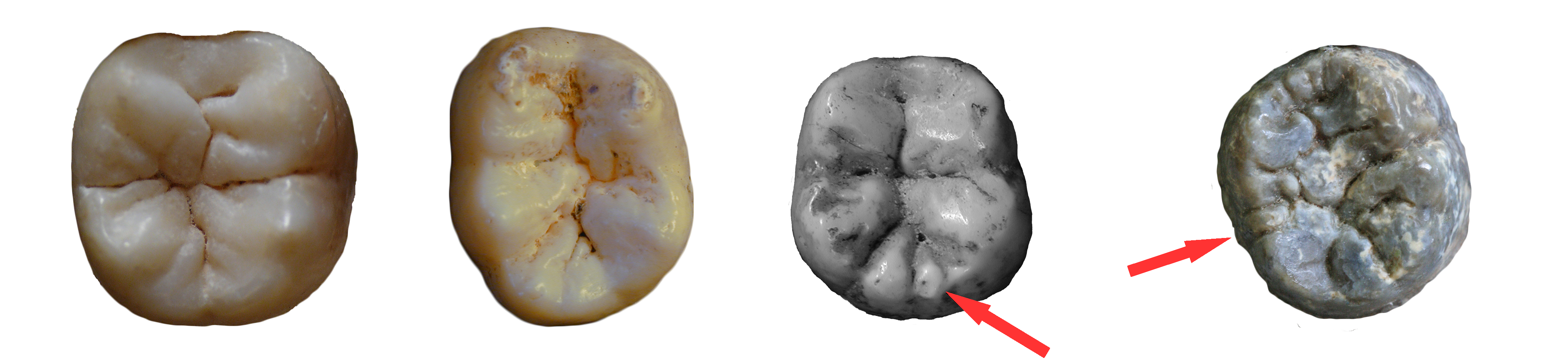

Locate your lower molars using your tongue. These are the back two or three teeth on each side of your lower jaw. Molars feel more square than your other teeth. Use your tongue to feel the cusps, or bumps, on your lower molars.

Focus on one tooth, try to feel how many cusps you have on that tooth. How many can you feel?

Take a closer look by making an impression of your lower teeth by biting into a soft, moldable material. A couple options are:

If using dental wax, soft candy, or a foam plate/tray, place the material over one of your lower molars and press it down. Gently remove from your tooth and check out the impression! (If using a mouth guard, follow the package instructions to make an impression of your lower teeth)

Go further and check your other molars. Is the number of cusps consistent in all of your molars? Compare your tooth impression to family members and friends.

What do the number of cusps on your teeth say about your ancestry?

According to dental anthropologists, the number of cusps can help them determine the ancestry of a Homo sapien specimen.

Molar images provided by Shara Bailey.

Shara Bailey is an associate professor in the Department of Anthropology at New York University in New York, New York.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. This week, scientists published details of a fossil find that may shake up our understanding of where and when humanity arose. The fossils are said to be of Homo sapiens from around 300,000 years ago, the oldest yet found. But they were found at a site in present-day Morocco, Northern Africa, not the more southern sites in Ethiopia’s Rift Valley that many had taken to be calling the Cradle of Humanity.

Not everyone is on board with this interpretation of the fossils, which was published this week in the journal Nature. But at the very least, it raises new questions about what it means to be a member of the species Homo sapiens.

Joining me now to talk about the find and other paleo-anthropological news is Shara Bailey. She’s an associate professor in the Department of Anthropology at New York University and is one of the authors of the new paper, and she is a specialist in teeth. Right, Dr. Bailey? She’s here with us. There you are. Welcome to Science Friday.

SHARA BAILEY: Thanks. It’s great to be here.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s talk about what was found in this Moroccan site– skulls, teeth, long bones. An incredible find.

SHARA BAILEY: Yeah, all sorts of things. And the great thing about it was that in this recent excavation, from 2004 on, we were able to supplement earlier finds from the 1960s. And because these new fossils were found in situ, and we were able to know exactly where they were, that allowed us to do a much better job of dating them.

IRA FLATOW: And going back that far, 300,000 years? That’s at least 100,000 years earlier.

SHARA BAILEY: Yeah. It’s incredible, isn’t it?

IRA FLATOW: So what does that mean about where we think that the Cradle of Humanity was in Africa? Because it upset the thinking about Ethiopia.

SHARA BAILEY: Well, I think what it means is when we think about a Cradle of Humanity, we have to think about it in terms of the entirety of Africa. So rather than being one specific place that modern human morphology originated. And, in fact, bits and pieces may have evolved in different places and then, of course, merged together as people merged together.

IRA FLATOW: Because we’ve had Homo naledi now found where it shouldn’t be? Right? We have those– what we call the Hobbits that are offshore. And doesn’t it seem to be that these– that maybe Ethiopia is an outlier?

SHARA BAILEY: Yeah, yeah. Well, it’s funny you bring up naledi because, you know, the dates on those are somewhere around the same time period. So what that means is you’ve got two different species clearly living at the same time in– and so probably, we’ll find them– modern humans. I imagine we’ll find modern humans this old in other places in Africa as well.

IRA FLATOW: And now, of course, you’re going to get– when you make such a claim about these fossils– you’re going to get some pushback from people saying extraordinary claims, extraordinary evidence.

SHARA BAILEY: I think we have extraordinary evidence, actually.

IRA FLATOW: Tell me why you mean that.

SHARA BAILEY: Well, you know, there– well, we did a very careful study of all aspects of the morphology of the skeletal material that is preserved– so the cranium and the dentition and long bones, et cetera. And everything points to them being– if they’re derived, they’re derived in a modern human way.

There are some aspects of the skull, of the endocranium, that are kind of primitive. They have rather large brow ridges, and the forehead is a little bit slopey. But there are aspects of the dentition– which, of course, is my specialty, as you mentioned– that are only found in modern humans. Only found in modern humans. So–

IRA FLATOW: Like what? What aspect?

SHARA BAILEY: Well, it’s hard to describe these things.

IRA FLATOW: You can get technical. You know, we like to get into the weeds here.

SHARA BAILEY: So on your lower molars, right? So these are your chewing teeth. There are all sorts of crests and cusps and things. And there’s a particular crest that we see in Neanderthal. It’s called a middle trigonid crest. So it’s a crest that connects the forward most cusps of your lower molar.

And if you– on the enamel surface, you can find this. It’s in a really high frequency in Neanderthals, and you can find it in, I don’t know, 15% of modern humans and maybe some Homo erectus. But when you take the enamel off and look at the dentine underneath– which is what we were able to do because these fossils were micro-CT scanned– that crest is only missing in Homo sapiens, OK?

So even in individuals– Homo erectus who don’t appear to have a crest on the enamel surface– when you take the dentine– the enamel off, the dentine preserves that crest. So far, the only species I’ve seen that are completely missing that crest are Homo sapiens. And then there’s other aspects of the molar shape.

I mean, we did have– the cool thing about this study is we included– we weren’t just saying, it’s not Neanderthal. Therefore, it must be Homo sapiens. We compared these fossils to other archaic Homo sapiens. We compare them to Homo erectus. And in every way, these fossils either fall completely within recent or early Homo sapiens variation or in-between something and Homo sapiens, like Homo erectus and Homo sapiens. So they never fall with erectines, which means it’s not primitive morphology. It’s changed since the ancestral pattern.

IRA FLATOW: You seem very energized.

SHARA BAILEY: It’s so exciting. You probably don’t see many people so excited about teeth, but–

IRA FLATOW: My dentist, but he’s getting paid to be excited about teeth.

SHARA BAILEY: I love it. You know, I was really– honestly when– you know, we’ve been working on this material for a long time. I mean, I knew– there’s a kind of a gestalt feeling you get when you look at teeth long enough. And I looked at them even before we did analyses. I looked– oh, they look modern to me.

What excites me is the age. And, you know, when they told me it was 300,000 years, I was like, what? Are you sure? What? You know. And are you really sure? And it’s very secure. And so for me, this is really exciting to push this back another 100,000 years.

IRA FLATOW: Because they also found some hunting tools and things like remnants of hunting. But to you, it’s the teeth that tell the story.

SHARA BAILEY: It is. The teeth tell the story.

IRA FLATOW: So would you say, then, that we’re on the cusp of another idea about– you know?

SHARA BAILEY: Yes, absolutely. And, you know, it also shows us that some aspects of the human body evolve earlier than others. So it looks like– and so, good for me, the teeth seem to be giving us the signal earlier than, let’s say, the skull. Even though the face is very modern, there are aspects of the skull that are kind of primitive.

IRA FLATOW: That’s fascinating. So you would assume, then, if we found these other fossils around Africa, there should be other places that we would find–

SHARA BAILEY: I think, you know–

IRA FLATOW: –equally old and fascinating fossils.

SHARA BAILEY: The genetic evidence suggests that Neanderthals and modern humans split somewhere between 500,000 and 700,000 years ago. Now, we know that we have Neanderthal ancestors in Spain at the site called Sima de los Huesos at least 400,000 years ago.

So why wouldn’t we have the beginnings of the modern human lineage going back even that far? So I think it’s possible that as we keep looking in Africa– I mean, it’s a big place– we might find additional fossils that are as old, if not older.

IRA FLATOW: Let me see if our listeners want to get in on this. Our number– 844-724-8255. You can also call us, if you like to use the Sci Talk number, 844-SCI-TALK. You can also tweet us @scifri.

You’re also involved with some other prominent fossil finds. I mentioned before the Hobbit and the Homo naledi. Did they match the teeth– the kind of teeth you found with this fossil? Are they different kinds of teeth on those fossils?

SHARA BAILEY: Oh, no. They’re completely different.

IRA FLATOW: Totally different.

SHARA BAILEY: Completely different, yeah. Homo naledi is a very odd– the dentition is very, very odd. It has a very strange combination of primitive characteristics, Homo characteristics, and derive towards some robust– it’s a very strange mosaic– chimera, if you will.

And Homo floresiensis– if you look at everything on the dentition except for the lower first bicuspid, it looks like a modern human, dentally. That lower first bicuspid is something I’ve never seen anywhere in the fossil record or the recent human material I’ve seen.

IRA FLATOW: You are the subject of our latest macroscope, our video.

SHARA BAILEY: Yes. Just came out yesterday, I think.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, a video on sciencefriday.com. And we came into your lab, and we shared your fascination with all these teeth that you look at. And when did you first start to get interested in teeth? Did people look at you weird when you said, I want to study teeth?

SHARA BAILEY: They do, yeah. They do.

IRA FLATOW: In a good way, I hope.

SHARA BAILEY: Yeah. And the first thing I look at people, unfortunately, are their teeth, so–

IRA FLATOW: I’m closing my mouth now.

SHARA BAILEY: You know, I was inspired by an article I read by Christy Turner from Arizona State University on how dental morphology– and those are the bumps and grooves and stuff with study on teeth– linked Native Americans to Northeast Asians. And at the time, I was very interested in Native American origins and in the Southwest.

And so a year after that, I packed up, and I moved to Arizona State University– or to Tempe– and studied with Christy Turner. And it was kind of just– it went off from there. He was a very inspirational teacher and mentor.

IRA FLATOW: And I noticed you give us a lesson on the video on the cusps, on the teeth. I didn’t realize how each one of our molars has a different number of those little bumps. They’re called cusps?

SHARA BAILEY: Yeah, yeah. Uh-huh. Yeah. So most people on their first molar have five cusps. And if you have four, you’re more likely to be European or of some kind of– some population that has a long history of farming because having four cusps is related to having smaller teeth. Having smaller teeth is related to having a long history of farming, for various reasons that have to do with your jaw is getting smaller.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s go to the phones with a call. Let’s go to California to– is it Rina in California?

RINA: Rina, right, from California.

IRA FLATOW: Hi, welcome.

RINA: Thank you. Hi. I was just– I had a question about how one gets into the science of teeth? I’m currently a biology major, and I’m interested in pursuing a PhD program. And I’m wondering how you go into that sort of thing.

SHARA BAILEY: Well, you apply to graduate programs, and you write a really good personal statement, and you connect with professors you might be interested in working with. I highly recommended doing that because when we have a name to put with– or a face to put with a name or something more than just your name on paper, it makes us more likely to consider you for our program.

IRA FLATOW: Good luck to you, Rina. Guess she’s gone. How do you go about being so sure of the dating of this last find?

SHARA BAILEY: Well, as I said, the new fossils were discovered in 2004. And they’re in situ, which means we know exactly where they were found. And so what they do with this kind of dating is– the dating is– one of the types of dating they used is based on trapped electrons. And so what you do is you put a dosimeter into the matrix in which the fossils were found, and you leave it there for a while. And then you measure the accumulation rate. And so in this way, we know exactly what the accumulation rate is of electrons in that particular part of the site.

With the materials that were found in 1960, they kind of knew where they were found, you know, and they did the same kind of things with the dosimeters. But this is much more accurate because we know exactly where they were found. And that’s why the date got pushed back a little more.

IRA FLATOW: Can we tell what they were eating?

SHARA BAILEY: Well, the faunal remains suggest they were eating large ungulates and large mammals.

IRA FLATOW: Really?

SHARA BAILEY: Yeah, yeah.

IRA FLATOW: So they were hunting? And killing?

SHARA BAILEY: Yeah, yeah. You can’t really tell from the teeth. We haven’t done any studies of the tartar, which– you know that stuff the dentist scrapes off your teeth? We could look at what their diet was based on that because both DNA and plant remains are contained in your tartar.

IRA FLATOW: Wow, wow, wow. I’m just–

SHARA BAILEY: Who knew, right?

IRA FLATOW: Who knows what’s in my tartar? This is Science Friday from PRI, Public Radio International. In case you’re just joining us, we’re talking with Shara Bailey, associate professor of anthropology at NYU and co-author of a paper in Nature this week.

And she’s also the subject of a new macroscope video on our website. If you want to know about teeth and her work, it’s an education. Sciencefriday.com/teeth. It’s also beautifully shot. How many teeth do you have in your lab, do you think?

SHARA BAILEY: Oh, hundreds.

IRA FLATOW: How many teeth do you think you’ve looked at over your career?

SHARA BAILEY: Oh, thousands. Thousands.

IRA FLATOW: Tens of thousands?

SHARA BAILEY: Maybe not tens of thousands, but certainly thousands. Because I’ve looked it teeth from most geographic populations that represent the world. And then I’ve– at this point, I’ve looked at, I would say, almost every fossil tooth that’s available for study. And that’s the topic of a book I’m working on, hopefully.

IRA FLATOW: Oh, a new book?

SHARA BAILEY: Yeah, it’s called The Evolution of the Human Dentition. I’ll probably sell about 200 of them by the end of– the only people in the world who are–

IRA FLATOW: Change the name a little bit. Make it a little sexier. I know about the publishers.

SHARA BAILEY: I’ll work on that.

IRA FLATOW: Right? Got to get Dracula on the cover or something. Let’s go to the phones. Let’s go to Ralph in Apple Valley, Minnesota. Hi, Ralph.

RALPH: Hi. My question was, how much have humans changed since then? If you dress these folks up in jeans and T-shirts, would they be indistinguishable from someone on the street?

SHARA BAILEY: Someone in New York City? No. No. They would– you would not pick them out of a crowd, especially if they had a hat on.

IRA FLATOW: Is that right?

SHARA BAILEY: They would just– yeah. Because the face below the eyes looks very– looks like us. It’s only the kind of slopey forehead that looks a little primitive. But I’ll tell you, I’ve seen some people with some big brow ridges around New York City, and so–

IRA FLATOW: Yes, not going there. Let’s go to Dan in New Jersey, speaking of around New York. Hi, Dan.

DAN: Hi. I was wondering if the new finds had any implications on the Bering Strait Theory.

SHARA BAILEY: Well, I think you might be talking about Native Americans coming across the Bering land bridge into– I’m sorry, Northeast Asians coming across the Bering land bridge into North America and peopling the Americas. That probably happened– I know there’s a recent claim for it– for finds dating back older than 100,000 years ago. I’m not convinced by that myself. But that migration probably only happened about 15,000 years ago. So these new finds are much, much older.

IRA FLATOW: Here’s a tweet from Brent Saunders. It says, “Understanding big swings in geotime. But what implications for how many hominid species living near or with each other at the same time?” I mean, of finding all these.

SHARA BAILEY: Yeah, yeah. No, it’s incredible because, you know, we think of ourselves and we look at ourselves today, and we can’t imagine another human species living at the same time. But, in fact, that was probably the norm rather than the exception. We are the exception now. Not just 300,000 years ago but a couple of million years ago, you had early Homo habilis living alongside robust australopithecines and, perhaps, other hominids as well.

IRA FLATOW: It’s one of the most interesting finds you’ve worked on? Yeah? Favorite?

SHARA BAILEY: Yeah, yeah. The Homo naledi stuff, I have to, say is pretty cool too because it’s so strange.

IRA FLATOW: You have a cool job.

SHARA BAILEY: Thank you. I think so.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. We thank you for taking time to be with us today.

SHARA BAILEY: Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Shara Bailey, associate professor in the Department of Anthropology at NYU and the topic of our latest macroscope video on sciencefriday.com. If you want to see why teeth make her so excited, you can check out our video. It’s right there on our website– sciencefriday.com/teeth. You can read how to read the cusps on your own molars from that video.

Copyright © 2017 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of ScienceFriday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.