From Atoms To Airplanes And Polymers To Planets

6:15 minutes

This week, the American Chemical Society held a national meeting in Orlando, Florida, giving a chance for thousands of chemistry professionals to present their latest work, including storing information in polymers, instructional lab experiments performed in virtual reality, and efforts to create a transparent, heat-storing material from wood.

SciFri director Charles Bergquist attended the meeting and joins Ira to share some highlights in this week’s News Roundup. They’ll also talk about some of the other news from the week in science, including an independent confirmation of methane observations on the surface of Mars.

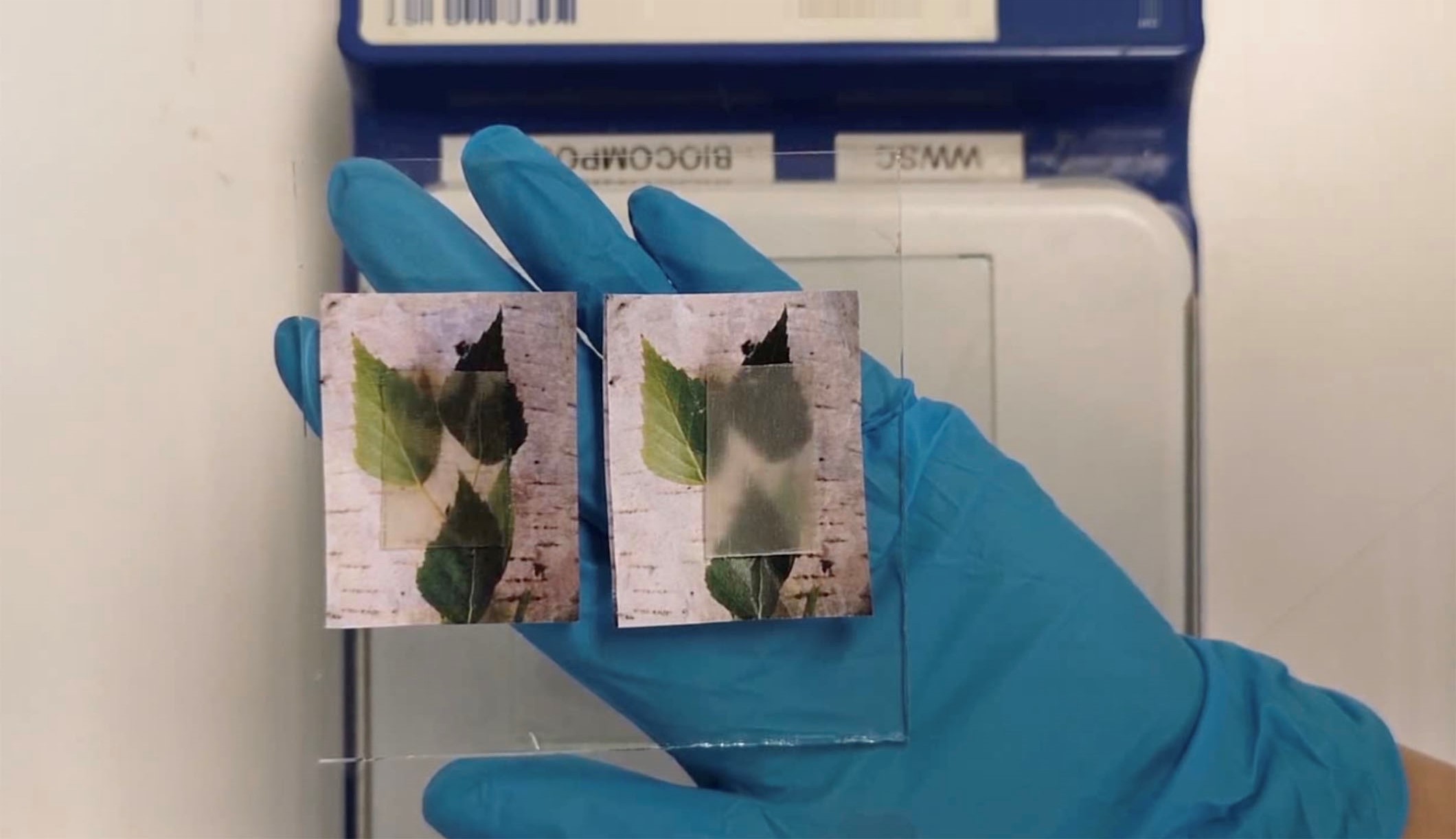

See a video of the transparent wood in action:

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Later in the hour, what the devastating floods in Iowa and Nebraska have done to the topsoil. But first, this week, thousands of chemistry professionals met in Orlando, not expressly for a trip to Disney World, but to discuss their research.

Sci-Fi Director Charles Bergquist attended the meeting of the American Chemical Society, and he is back to share some highlights. Welcome.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Hi.

IRA FLATOW: Before we get to the meeting, there is some news out this week about chemistry elsewhere in our solar system on Mars.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: That’s right, Ira. So this week in the journal Nature Geoscience, with some findings published about methane. You might remember back in 2013 the Mars Rover Curiosity reported seeing increased levels of methane in the air around Gale Crater. The news this week is that the European Space Agency’s Mars Express Orbiter apparently spotted methane in the same area, at the same time.

IRA FLATOW: Oh.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Yeah. So it’s an independent confirmation of that original methane sighting.

IRA FLATOW: But we don’t know where the methane originated. Well it’s a big–

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Well–

IRA FLATOW: That’s a big issue, isn’t it?

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Yes and no. So they have an idea now of the geographic feature that they think it might have come from near the crater. But they don’t know what caused it. And, of course, there are both biological sources of methane and geologic sources. So it’s still up in the air.

IRA FLATOW: You’d like to think it was life, wouldn’t you? But is there any way to narrow this down?

CHARLES BERGQUIST: So there’s another European spacecraft called the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter that arrived at Mars in 2017. It hasn’t put out any data yet. So planetary scientists are really going to be keeping an eye on that one.

IRA FLATOW: All right. Let’s get to the Chemical Society meeting this weekend. There was something about transparent wood.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Yeah. So this is a little involved. But if you imagine taking your regular, ordinary piece of wood, it turns out that there’s two main components in the wood. There’s lignin and there’s cellulose. And lignin is the stuff that gives it most of its color and why you can’t see through it.

So if you manage to wash away the lignin, you’re left with just the cellulose. It’s like these whitish fibers in a network. And if you fill the space in between the fibers with some– a material that has the right optical properties, the fibers essentially disappear, and you can see through the wood. You’ve made a composite material that still has a lot of the wood-like properties, but you can see through it.

That’s not the news here. That was done a couple of years ago. You can actually find demos of how to do it yourself on YouTube if you don’t mind messing with a few chemicals. But what these researchers have done now from the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm is they’ve found that if you take a material called a phase change material, which is something that soaks up or releases a lot of heat when it melts or freezes, you stuff that into the pores. You now have a transparent piece of wood that– imagine if you made a roof panel out of it.

IRA FLATOW: Right, right, right.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: During the day, it would melt. It would soak up some of the excess heat, reduce the temperature a couple degrees. And at night when it cooled, it would release that energy back out and give you a little bit of extra warmth.

IRA FLATOW: Hey, so do we know if anybody’s building anything?

CHARLES BERGQUIST: You know, they’re playing with it. And I think it’s probably not going to be in your roof panels anytime soon. But, yeah. It’s interesting.

IRA FLATOW: I want some of that stuff.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Yeah, totally.

IRA FLATOW: And I remember reading years ago about another woody type project like that where the wood actually soaked up the heat during the day and let it go at night.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Yeah, it’s interesting. It’s a great concept because it’s passive heating, right?

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Right.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. You saw a VR chem there also. Chemlab.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Chemlab. So this is a teaching lab for students learning organic chemistry. And this is a group at North Carolina State University. And they emphasize that they don’t want to do away with Chemlabs. They’re not looking to do that.

But this is for intended for people who maybe, say, they get pregnant and they can’t go into the chem lab.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: You can’t for safety reasons, or they’re in the military and they get deployed, they need some other way of finishing out the required lab. So in this, you put on the goggles, and you see your hands walking around the lab, and they’ve filmed– can you imagine having the best TA in the entire university, talking just to you, to explain to you how to do that thing.

And what’s cool is that they broke up a class into two sections and some people use the VR demo. Some used the actual, physical, regular lab. And at the end, they graded the lab reports blindly. And they did the same on the lab reports.

IRA FLATOW: You weren’t able to try this one out, did you?

CHARLES BERGQUIST: I–

IRA FLATOW: You did?

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Yeah. I–

IRA FLATOW: You put it on?

CHARLES BERGQUIST: I put it on and–

IRA FLATOW: So what did you see? What kind of lab?

CHARLES BERGQUIST: I mean, it’s– they actually filmed– you know, it’s not– this isn’t a cartoon.

IRA FLATOW: Right.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: This is filmed in a real lab. So it looks like– well, they did clean it up. So it’s the cleanest lab you’ve ever been in, right? But, yeah, there’s a lab and a TA. And you can open the drawers. It’s–

IRA FLATOW: And you can pull things, and touch things, and pick things up?

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Right.

IRA FLATOW: Virtually?

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Yeah. You don’t do it with– you’re not wearing gloves or anything. It’s not done with your hands. But it’s– you can look at something intently, and that tells you to activate that function on the instrument, or whatever.

IRA FLATOW: I want one of those. And there’s some look ahead news for next week. This could be pretty exciting, right?

CHARLES BERGQUIST: It could be. So what’s cool is the astronomers involved in a project called the Event Horizon Telescope have announced that they’re making an announcement. They’ve announced an announcement, for next Wednesday. And we don’t know what it is.

But the entire purpose of that project was to try to take a picture of a black hole. So either maybe they’re going to show us a picture of a black hole, or they’re going to tell us that black holes don’t actually exist, and something like that.

So if you want more information about this, we can prep you on it. There’s some of an interview that we recorded a couple of years ago with one of the lead researchers. And it’ll be in our podcast feed. So you can check that out.

IRA FLATOW: Of course, since a black hole is black, we won’t see the hole. We’ll see the event horizon.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: That’s why it’s called the Event Horizon Telescope.

IRA FLATOW: They are so clever. So are you, Charles. Thank you for taking time to be with us today.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Thanks, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Science Friday’s Director and contributing producer.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.