What Could Happen To IVF In A Post-Roe World

35:01 minutes

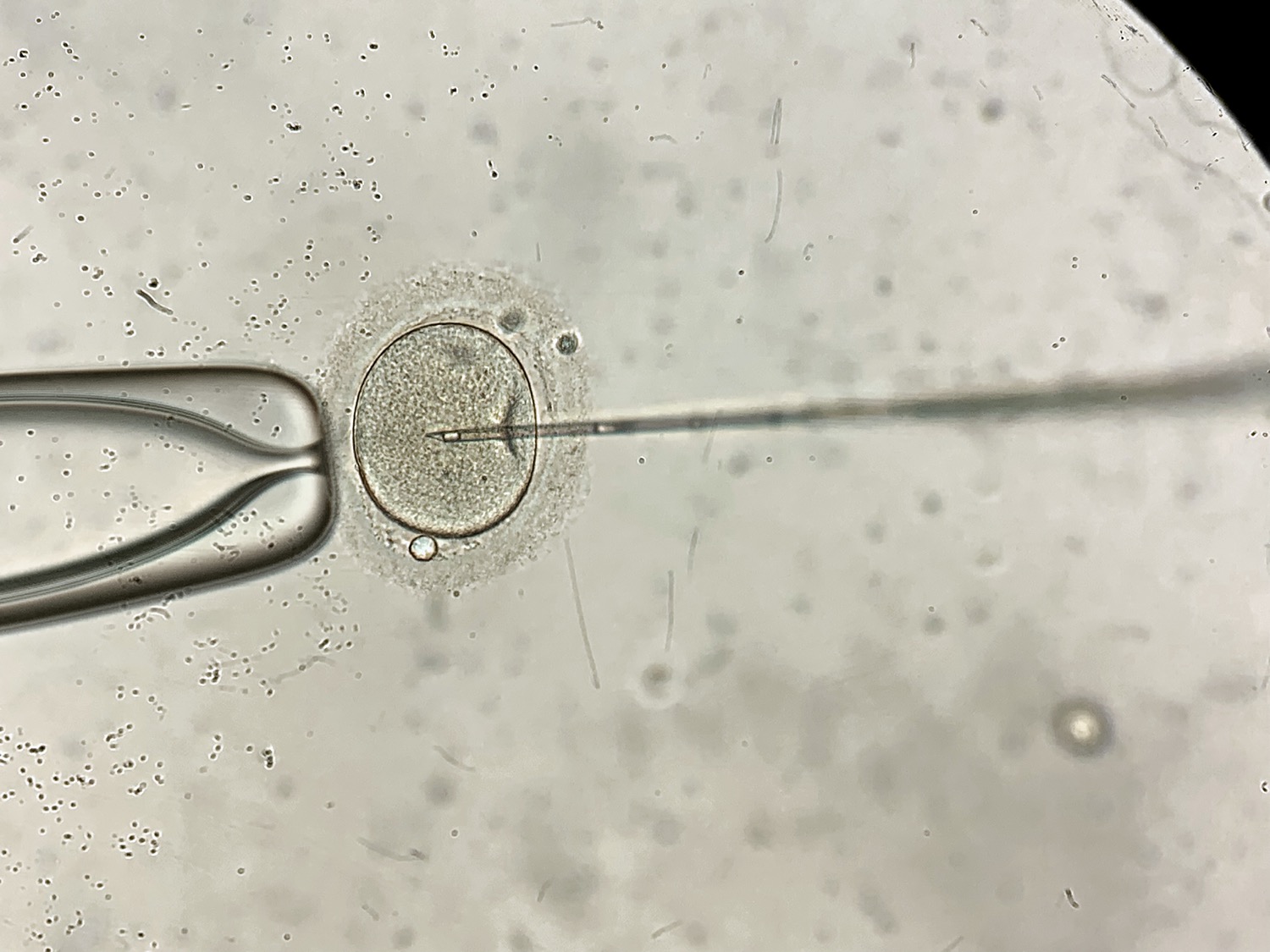

An overturn of Roe v. Wade could have rippling effects far beyond access to abortions. Some state laws designed to ban or severely restrict abortion could also disrupt the process of fertilizing, implanting, and freezing embryos used in in vitro fertilization. That’s because some of these laws include language about life beginning at conception, raising questions about in vitro fertilization’s (IVF) legality.

An overturn of Roe v. Wade could have rippling effects far beyond access to abortions. Some state laws designed to ban or severely restrict abortion could also disrupt the process of fertilizing, implanting, and freezing embryos used in in vitro fertilization. That’s because some of these laws include language about life beginning at conception, raising questions about in vitro fertilization’s (IVF) legality.

Roughly 2% of all infants in the United States are born following the use of some form of artificial reproductive technology. While that figure might seem small, it’s nearly double what it was just a decade ago.

Ira talks with Stephanie Boys, associate professor of social work and adjunct professor of law at Indiana University, about the legal implications of an overturn of Roe v. Wade on IVF treatment. Later, Ira also interviews Dr. Marcelle Cedars, director of the division of reproductive endocrinology at UC San Francisco and president of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, about the science behind IVF and what people often get wrong about when and how life begins.

This segment is part of Science Friday’s continuing coverage of the science behind reproductive health.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Stephanie Boys is an associate professor of Social Work and an adjunct professor of Law at Indiana University in Indianapolis, Indiana.

Marcelle Cedars is President of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and Director of the Division of Reproductive Endocrinology at UC San Francisco in San Francisco, California.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. We’re continuing our coverage of the ripple effects of what an overturn of Roe versus Wade on access to reproductive health care in this industry might ripple into. This week we’re looking into In Vitro Fertilization, or IVF, as you may know. Roughly 2% of all infants in the US were born using some form of artificial reproductive technology. And while that number might seem small, it’s nearly double what it was just a decade ago.

If Roe is overturned, roughly half of states would ban or severely restrict access to abortion. But how many of those laws would ban in vitro fertilization also? To get a legislative lay of the land, I recently spoke with Stephanie Boys, Associate Professor of Social Work and Adjunct Professor of Law at Indiana University based in Indianapolis.

STEPHANIE BOYS: I think it’s really hard to say exactly until we see these laws go on to the books. What I’m looking at is the language of when they say that abortions can no longer be performed. There are three camps going on right now.

There are those states that would ban abortion after a certain number of weeks. Six weeks seems to be fairly common. It’s pretty difficult to actually get an abortion prior to six weeks of pregnancy. So there are those states, and those wouldn’t affect IVF.

And then there are states that are specifically using language that discusses the word implantation. And when we talk about implantation, with IVF, the eggs are retrieved. They are fertilized outside of the human body. And then they are transferred to a female uterus. At that point, implantation happens.

So if we talk about implantation, we could still have a creation of embryos, and it wouldn’t affect too much the fertility treatment services going along with IVF. What I’m concerned about, specifically with IVF, is those states, such as Oklahoma, that have already defined abortion as not being permissible after fertilization or conception.

If we talk about fertilization or conception, with IVF, that happens in the Petri dish. It’s very, very unclear what would happen to the process of IVF. Because if we’re now saying, OK, these embryos have rights, are we saying that you can no longer cryopreserve embryos? Are we saying that we can no longer destroy embryos? Because those are things that are happening very commonly in the United States right now.

IRA FLATOW: If it’s a crime to destroy the embryos, and these embryos that are in storage have lost the people, or they’ve lost track of the people who created them, and now it’s up to the storage facility to keep them alive and pay for that, if they wanted to go ahead and not preserve them, and if they’re considered to be human life, then it would be a crime to let them just go away, would it not?

STEPHANIE BOYS: Absolutely. It absolutely would. One of the issues in the United States is we don’t have many regulations at all on IVF. We don’t have a lot of data on what these clinics are doing. And so no one is really sure in the United States how many embryos we have cryopreserved.

Estimates are generally it’s over a million at this point and growing pretty quickly. And so, if states were to say life begins at conception, it would absolute income crime to destroy these embryos. So we’ve got all of these embryos that are already created. So that’s one side of the issue. And then, for couples that are coming in or individuals coming in wanting IVF treatment now, would they be allowed to cryopreserve?

Because what some countries have done is just done away with cryopreservation. There have been countries in Europe that have experimented with just not permitting cryopreservation, just saying all embryos that are created in an IVF cycle must be transferred also in that cycle, so in about five days after the creation of the embryos.

IRA FLATOW: Back in 2019, I know you decided to look into the ramifications of fertility treatments if Roe v. Wade was overturned. And that was right about when Justice Brett Kavanaugh was sworn in. Did you think that this would become a reality?

STEPHANIE BOYS: No. I honestly didn’t think that this would become a reality. I wrote that paper for a policy advocate audience. I wanted folks to be informed about the ramifications of overturning Roe v. Wade on IVF treatments because I feel like there are a lot of policymakers and a lot of lawmakers out there who haven’t thought through all of the unintended consequences of overturning Roe.

And so I wrote this paper to inform policy advocates about how they could go out, explain this issue to lawmakers, and hopefully, convince policymakers of the importance of maintaining Roe v. Wade and the precedent.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm. And what about genetic testing of embryos before implanting them, which is very common? How would that be affected by overturning Roe v. Wade?

STEPHANIE BOYS: So going along with IVF, once the embryos are created, most couples are offered an additional service, which is called PGT, Pre-Implantation Genetic Testing where the embryos are biopsied. And they’re biopsied for any genetic abnormalities. It’s also up in the air.

I think it would go before courts. If this would be permitted, would we be allowed to discard of embryos with abnormalities parallel to what some of the states have been doing where states have banned abortion based on certain reasons if the abortion was because of a genetic abnormality that was found after the pregnancy was created when there’s genetic testing during the pregnancy?

With PGT, we can actually do genetic testing before a pregnancy is even created, before implantation. And it actually gets very, very complicated as well with people crossing state lines. People might live in one state. There aren’t actually a lot of labs in the United States doing PGT. And so you might live in one state where it’s illegal, but yet have your embryos frozen and transferred to another state where the labs will do PGT, do the testing, send them back to the state where you’re getting your services where it’s legal.

IRA FLATOW: Could the overturn of Roe v. Wade lead to a push to better regulate the IVF industry?

STEPHANIE BOYS: I absolutely think that it would lead to a push to regulate the IVF industry as well as the fertility industry. As I said before, there are very few regulations in the United States right now. It’s very often referred to as the Wild West. And so I think we would see more regulation, or at least a push for regulation.

In my 2019 paper, I looked at what some other countries had done. And generally, other countries who have this legal ideology of life beginning at conception while also wanting to balance the availability of IVF services, there are generally three things that come up.

One is that the countries might limit the number of embryos that are created each cycle so that we have less excess embryos created. The second is that some countries will actually require that all embryos created in a cycle are transferred so that we don’t have any leftover. Some countries ban the use of cryopreservation so that we, again, don’t have any leftover embryos.

My thought is that we’re going to see a lot of lobbying in this area from health care providers and from the pharmaceutical industry because IVF is such a lucrative industry, a lot of lobbying for exceptions for IVF within these laws that define life as beginning at conception or fertilization.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you, Stephanie, for taking time to be with us today.

STEPHANIE BOYS: Thank you so much for having me on.

IRA FLATOW: Stephanie Boys is an Associate Professor of Social Work and Adjunct Professor of Law at Indiana University. And if you would like to get in on the conversation, we’d like to have you. If you’re wondering or have questions about how an overturn of Roe v. Wade could impact fertility treatments, or you’re just curious about the science behind IVF or about the science behind conception and fertilization, we’re happy to revisit the birds and bees with you on this one.

So give us a call. Our number is (844) 724-8255. That’s (844) SCI-TALK, or you can tweet us @SCIFRI. And joining me now to dig deeper into the science behind In Vitro Fertilization and take your calls is Dr. Marcelle Cedars, Director of the Division of Reproductive Endocrinology at UC San Francisco and President of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Dr. Cedars, welcome back to Science Friday.

MARCELLE CEDARS: Thank you very much.

IRA FLATOW: We just talked about the possible state legislation that defines life beginning at conception when the sperm meets the egg. Let’s talk about how this all works. What’s the likelihood that a recent fertilized embryo would come to term?

MARCELLE CEDARS: Well, I think that’s a really critical question. And even in nature, the best possible environment for that embryo, only about 25% of fertilized eggs will be a successful birth.

IRA FLATOW: 25%. One in four.

MARCELLE CEDARS: One in four.

IRA FLATOW: Huh. So at the–

MARCELLE CEDARS: And that can go down as women get older because of increased genetic risk.

IRA FLATOW: So some women may try to do it a few times just to have a success.

STEPHANIE BOYS: Well, think about natural conception, how many months it might take a woman to conceive. So we’re not even talking about multiple cycles of IVF. We’re just talking about the reality in nature, which is why the concept that life begins at conception is really not consistent with scientific knowledge.

IRA FLATOW: And that’s something I want to get into next because I think, as you point out, at the heart of the controversy is the definition of when a human life begins as expressed, I think, in this question from one of our listeners.

SPEAKER 1: Why can’t science tell us when life begins?

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Cedars, why can’t science tell us when life begins?

MARCELLE CEDARS: Well, I think it depends how you define life. And so, I think the lawyers of the Supreme Court with the Roe v. Wade decision understood how complex that question is, which is why they talked about viability as in could live outside the womb as an independent entity.

And I think that’s really the best definition that we have because when life begins is so complicated by religion, by belief, by things that aren’t necessarily shared by all of us. And I think it is something that is a complex question. And scientifically, we talk about life as living as an independent entity.

IRA FLATOW: For our listeners who may not be intimately familiar with IVF, Dr. Cedars, explain for us how the process works a bit. Would you?

MARCELLE CEDARS: Sure. There’s really three main aspects of IVF. The first is to give medications that increase the number of eggs a woman will ovulate in a single cycle. In a normal cycle with no medications, a single egg is ovulated. We’ve seen since IVF was created to improve the efficiency and the success rates, that getting more than one egg in any given cycle is useful.

So there’s about a 10 to 12-day period of taking injections that stimulate the ovary. Then there’s the egg retrieval process whereby we take the eggs out of the ovary and bring them into the laboratory. We get sperm that same day. Put the eggs and sperm together. And then we grow the embryos in the laboratory, typically till day five or six, at which time, they can either be transferred or frozen.

IRA FLATOW: Hmm. Very interesting. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. We’re talking with Dr. Marcelle Cedars, President of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine about in vitro fertilization. I know that there’s a recent advance in IVF, allowing embryos to develop longer outside of the body. What are the benefits of this process, and how would an abortion ban at conception impact this method?

MARCELLE CEDARS: So in the past, when IVF was new, embryos would be transferred on the second or third day after the egg retrieval. But with improved culture conditions, we can now grow them till day five or six to what’s called the blastocyst stage. It’s important to know, as would happen in your body, about half of these fertilized eggs don’t even make it to the blastocyst stage in the laboratory.

But the advantage of doing that is it’s a bit like asking the embryos to run a marathon. And you’ve been able to identify the healthiest of the embryos, which has led to the biggest improvement in IVF safety, which is the fact that we can now transfer just a single embryo. And so we’ve markedly decreased the risk of even a twin pregnancy, and certainly eliminated the risk of a triplet pregnancy.

And multiple pregnancies in the past have been the greatest risk, both to the mother and the resultant child in terms of complications. So being able to grow the embryo longer, select a better embryo, transferring only one has been hugely important to improving the safety and health of IVF.

IRA FLATOW: And the embryos may go through genetic screening that often occurs before embryos are implanted, correct?

STEPHANIE BOYS: They may or may not, on that day five or six, go through genetic screening. That would allow you to identify an embryo, for instance, that might be affected by Tay-Sachs, which is a universally fatal disease and really mortality for young children. Parents could identify an embryo that might be affected by something like Tay-Sachs and then exclude those embryos from transfer so that there’s a greater likelihood of having a healthy child.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm. I want to go to some of the tweets and phone calls that are coming in. We’re going to take a lot more calls after the break, which is just about a minute and a half. But I have a tweet from Serena on Twitter. She says, “worried about impact of demise of Roe v. Wade on IVF. Young doctors in training are saying they will not take jobs in states that prevent full care of infertility patients. This will make the poor access to infertility treatment in this country even worse.” Your comment?

STEPHANIE BOYS: I think that’s spot on. This is access to care whether it’s general health care or access to fertility care is severely compromised in the US. And unfortunately, it’s many of the same states that would have the most restrictive abortion laws are states that already have poor access to care for general maternity care, have higher maternity mortality rates.

And so I think that’s absolutely true, especially since most obstetrician gynecologist these days are women. They may choose to either train or practice in states that get in between the patient and the doctor in terms of making the best evidence-based decision.

IRA FLATOW: All right, we have a lot more calls. Our number (844) 724-8255 if you’d like to get in on the conversation. We’ll be right back after this short break with Dr. Cedar and your phone calls and questions.

This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. If you’re just joining us, we’re talking about the impact a Roe v. Wade overturn. What impact might that have on In Vitro Fertilization? My guest is Dr. Marcelle Cedars, Director of the Division of Reproductive Endocrinology at UC San Francisco. And she is also President of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine.

Our number, (844) 724-8255, SCI, (844) SCI-TALK if you like, or you can tweet us @SCIFRI. So many people have questions. Let’s go right to them. Let’s go to the phones. Let’s go to Emily in the Bronx. Hi, Emily.

SPEAKER 2: Hi. Thanks for taking my call.

IRA FLATOW: Go ahead.

SPEAKER 2: Hi. So just to start, I want to say I have two children who were conceived via IVF. And I appreciate the conversation about this.

My question is about how before the last few months in this news with Roe v. Wade, most of the conversation that I’ve been in around IVF has been around genetic testing and genetic manipulation and what the future holds for regulations in those areas. And that alone was its own big scary topic. And I thought that would be the main focus in the scientific and medical community. So I’m curious how the conversation may have shifted, and if the two pieces are being talked about together?

IRA FLATOW: Good question. Dr. Cedars?

MARCELLE CEDARS: I think our bigger concern is really more basic. Because if there are additional laws like the current law that was recently passed in Oklahoma that states that life begins at fertilization, our concern is can we continue to practice IVF in a safe and efficient manner? So can we cryopreserve at fertilized eggs? Can we continue to do pre-implantation genetic testing? Those issues that were brought up by the prior speaker.

And that’s a serious question in terms of how do we continue to do IVF in the best, safest way for patients so other families can be built the way yours has been? So I think we really have focused on these very basic questions about what these laws might mean.

IRA FLATOW: Thanks for the call. Let’s go to the next– let me go to a tweet. This is an interesting tweet because it’s from Rebecca on Twitter. She says, “It sounds like the richer people will have their interests protected with commercial interests, lobbying for IVF. While poor women will be impacted by lack of access to abortion.” Dr. Cedars?

MARCELLE CEDARS: Well, I think that’s a very good point. I mean, ASRM has been very active in supporting all regulation that restricts decisions between a doctor and a patient. And that includes abortion. And we have joined with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists on a number of amicus briefs.

We were strong supporters during COVID of allowing consultations for abortion to occur with telehealth and not requiring in-person visits since most abortions in the US are by medical treatment and not surgical. So in our minds, these are intimately created or connected. Reproductive health is really the ability to conceive and build a family when you want to and to not have a child when you don’t want to.

So it’s really a spectrum, and these two things cannot be disassociated. So I wouldn’t disagree with you. And that’s why we are advocating for abortion rights and leaving these decisions to doctors and patients.

IRA FLATOW: Go to the phones to Lisa in Rockaway, New Jersey. Hi, Lisa.

SPEAKER 3: Hello.

IRA FLATOW: Hey there. Go ahead.

SPEAKER 3: So it’s so upsetting. Because as somebody who has been through four IVF retrievals and have only gotten one good embryo plus a fifth with a donor, this is the type of situation where it’s really scary. When you have an abnormal embryo, if you’re asked or told that you have to transfer that embryo– something that’s not compatible with life– it puts you in a really upsetting and scary situation.

I had a miscarriage in which I had to have a DNE at 12 and 1/2 weeks. It was the worst experience I’ve ever been through. And as somebody who wanted to be pregnant that badly, to have people telling me that they know more than science, perhaps because religion is intertwined into it, it’s beyond my comprehension.

IRA FLATOW: Hmm. Go ahead, Dr. Cedars, what have you got to say about that?

MARCELLE CEDARS: I’m with you. That’s exactly what we’re concerned about is that patients will be put into these very difficult situations or be told that they can’t discard embryos once they’ve completed childbearing, and they might be forced to donate them. And so you might have an affected– a genetic child that is being raised by another family, which is a wonderful gift if you choose to do it. But if you don’t choose to do it, it could be quite difficult.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you, Lisa. Yeah, this brings me to a tweet actually, the same that came in. It says, “if embryos are granted personhood, does that mean,” Beth asks, “that cryopreserved have to be born? Would women who have fertilized eggs frozen be compelled to carry them to term?” And I think that’s what Lisa was talking about.

MARCELLE CEDARS: I think that is– would they be compelled to carry them to term, or would they be compelled to continue to pay storage on them indefinitely if they chose to transfer them from a state that restricted their ability to make decisions to a state that didn’t? Would they be forbidden from doing that? That can now happen to ship embryos from one state to another. But just as they’re restricting on the side of abortion, being able to bring in abortion medications to states through the mail or through delivery, could you be forbidden to transfer your embryos out of state to discard them?

IRA FLATOW: And what about where the embryos are stored in fertility clinics? Would those clinics be required by law to keep those embryos viable or else be accused of murder?

MARCELLE CEDARS: Well, I mean, I think that’s a scary point because not all embryos will survive freezing and thawing as I mentioned before. Not all embryos will survive culture in the laboratory. So will the physician or the laboratory be accused of murder if an embryo doesn’t survive when we know as your very first wives’ question we know in nature, only one out of four is capable of going to birth.

IRA FLATOW: Our number, (844) 724-8255. Lots of folks. Let’s go out to the coast to Ethan in Portland. Hi, Ethan. Welcome to Science Friday.

SPEAKER 4: Hi, how are you?

IRA FLATOW: Hi, go ahead.

SPEAKER 4: Yeah, I just wanted to make the point that I think that a lot of the people who are pro-life and going to make these abortion and IVF bans, do so and saying like, well, we want to have a family. And I just had my third daughter born two weeks ago today with IVF. And I want to make the point that without that ability to have IVF, I couldn’t have had the family my wife and I dreamed of.

IRA FLATOW: Oh, wow. Congratulations to you.

SPEAKER 4: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, it’s making possible– IVF is making children possible for a lot of people. Now, I understand, Dr. Cedar, that you have spoken to colleagues who are planning to encourage patients to undergo IVF to be able to screen for genetic abnormalities ahead of getting pregnant so that if abortion for genetic issues becomes a crime, then you won’t get pregnant and risk need having an abortion later. Is that correct?

MARCELLE CEDARS: Well, I don’t know that people have been encouraging patients to do that at the present time, but I think that’s a theoretical possibility that will be there. So if you happen to be in a state that prevents abortion, say, after six weeks, so it wouldn’t interfere with the process of IVF, but it would eliminate the risk of doing a termination later in pregnancy, even if the embryo, the fetus was found to be carrying a genetic deficiency.

It may push patients who might not otherwise need IVF to do IVF. It might push physicians and patients to discuss doing genetic testing that perhaps they wouldn’t otherwise do.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s go to Dan in Oxford Connecticut Hi. Welcome to Science Friday.

SPEAKER 5: Yeah. Hello.

IRA FLATOW: Hi, Dan.

SPEAKER 5: Can you hear me?

IRA FLATOW: Yes. Go ahead.

SPEAKER 5: Yeah. Hi. I just wanted to get the doctor’s comments. I got a patent actually pending right now for the cryopreservation process. We are using a Stirling engine. So this would be a new method that wouldn’t really need liquid nitrogen so it might be safer for the lab technicians. And I just wanted to see if the doctor has heard about this solid-state freezing as opposed to liquid nitrogen and get her comments on that.

IRA FLATOW: OK.

MARCELLE CEDARS: Yeah, I haven’t really heard that much about it, so I can’t comment. But I think in terms of the issue of viability, and whether or not you’d be able to freeze excess embryos, and then what you can do with an embryo once it’s frozen, I think those issues would be the same regardless of the technology that you use to freeze them.

IRA FLATOW: Thanks, Dan. Good luck with your patent.

SPEAKER 5: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: Another Twitter coming in from Erica who says, “There is a huge financial aspects for patient. It’s ideal to create as many embryos as you can in one cycle because you may not be able to pay for another one. I wouldn’t have had my daughter now if I couldn’t freeze embryos after a cycle. Limiting that could be detrimental.”

MARCELLE CEDARS: I think that’s a very good point. And again, as I said, going to stimulation of the ovary versus for instance Louise Brown, who was a single-egg ovulated, the first IVF birth in 1978 in England. Increasing the number of eggs in a single cycle does increase the safety as well as the success rate because it allows you to have to go through the process less.

And so the caller is absolutely right. It particularly, as most states don’t have mandated coverage, despite infertility being considered a disease that if patients are paying out of pocket as efficient as we can make the process for patients, the less expense they’ll have.

Mm-hmm. Talking about in vitro fertilization with Dr. Marcelle Cedars, President of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and Director of the Division of Reproductive Endocrinology at UC San Francisco. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. Let’s go out to the phones to Cheryl in Santa Cruz. Hi, Cheryl.

SPEAKER 6: Yes. Oh, OK. Sorry. Ah, here we go. I’m in my car.

[LAUGHS]

Can you hear me?

IRA FLATOW: Yes. Go ahead. I hope you’re not driving.

SPEAKER 6: I’m not. No, I pulled over. Thank you. I just wanted to say that since this whole thing has come up that any type of fertilized human egg would be in jeopardy of in regards to what you’re talking to today as well as stem cell research. Because I do believe they need fetal tissue, and I do believe I heard– correct me if I’m wrong– that they actually fertilized human eggs in order to use the fetal cells to make stem cells. And so all that would have to stop.

And then what happens if Roe versus Wade gets reversed? Does that mean any woman who’s pregnant will be supported by the federal and state government in order to carry that baby to a healthy term and help them adopt, put it up for adoption if they don’t really want to have a child?

IRA FLATOW: Interesting. Interesting questions, Cheryl. Let’s go to the first part about stem cell research, Dr. Cedars.

MARCELLE CEDARS: Yeah, I think it’s an interesting question. I mean, nowadays a lot of stem cell research are done with skin cells or other type of cells. And we’re not using embryos, human embryos as much. Generating new stem cell lines from human embryos are actually not covered, not allowed by the national government in the US. It’s one of the problems with abortion and IVF having been closely linked really since the 1980s.

We’ve been unable to do federally-funded embryo research in the US. So, for us, unfortunately, there are already restrictions about that. Countries like the UK that may have more guidelines for how to practice IVF actually allow embryo research up to 14 days of age. So I’m not sure that this specifically will hurt that research since most has shifted to what are called IPS cells that don’t involve embryos. But it certainly may continue to restrict embryo research.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm. Thank you, Cheryl, for that question.

SPEAKER 6: Yes. And may I make one more comment?

IRA FLATOW: Sure.

SPEAKER 6: Yeah. So I appreciate people having whatever religion they want as well as having morals. But I also don’t want them to make me sign up for their religion or their morals. And I thought there was a separation between church and state, so having laws that give us resources to have freedoms here in the United States.

And we’ve tried so hard to get our freedoms. We shouldn’t have them taken away by people who say their religion doesn’t like what we’re doing. So there’s that old adage if you don’t like a person, don’t have one.

IRA FLATOW: OK, Cheryl. Thank you for your comments. A lot of people are going to be talking about this, Dr. Cedars. This is certainly going to explode rather than go away.

MARCELLE CEDARS: No, I think you’re right. And to the one caller who was talking about abortion decisions in general and to the last caller, I think you’re right. And as the young man who just had his third child, I’ve had patients who are Catholics. And they say my whole life, I’ve been told to build a family and raise them in the church.

The only way I can do that is through IVF. How can someone tell me that’s wrong? And they’ve chosen to go forward because the bigger priority in their mind is being able to build their family. And so I think that the abortion wars have been such a prominent part of US politics for so long, that I’m surprised and disappointed to see us moving in the direction it appears that we are.

IRA FLATOW: Well, I want to thank you for taking time to be with us and answering our questions today, Dr. Cedars.

MARCELLE CEDARS: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Marcelle Cedars, President of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, Director of the Division of Reproductive Endocrinology, UC, San Francisco.

Here’s Kathleen Davis with some of the folks who help make this show happen.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Thanks, Ira. Nahima Ahmed is our manager of impact strategy. Valissa Mayers is our office manager. Annie Nero is our individual giving manager. Charles Bergquist is our radio director. And I’m Kathleen Davis, radio producer.

IRA FLATOW: And thanks.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Thanks for listening.

IRA FLATOW: Well, thank you, Kathleen. And we had help this hour from audio engineers, Lisa Gosselin and Kevin Wolfe. B.J. Leiderman composed our theme music. And if you missed any part of the program or you would like to hear it again– yeah, this is certainly that kind of program– subscribe to our podcast or ask your smart speaker to play Science Friday. Have a great weekend. I’m Ira Flatow.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/.

Shoshannah Buxbaum is a producer for Science Friday. She’s particularly drawn to stories about health, psychology, and the environment. She’s a proud New Jersey native and will happily share her opinions on why the state is deserving of a little more love.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.