Money Mark Is Reviving Dead Pianists

12:29 minutes

Debussy would’ve had a blast jamming out on a Moog synthesizer. Or at least, that’s what Mark Ramos Nishita, more popularly known as Money Mark from the Beastie Boys, imagines the classical musician’s reaction might have been had he stuck around long enough to see synthesizer technology flourish.

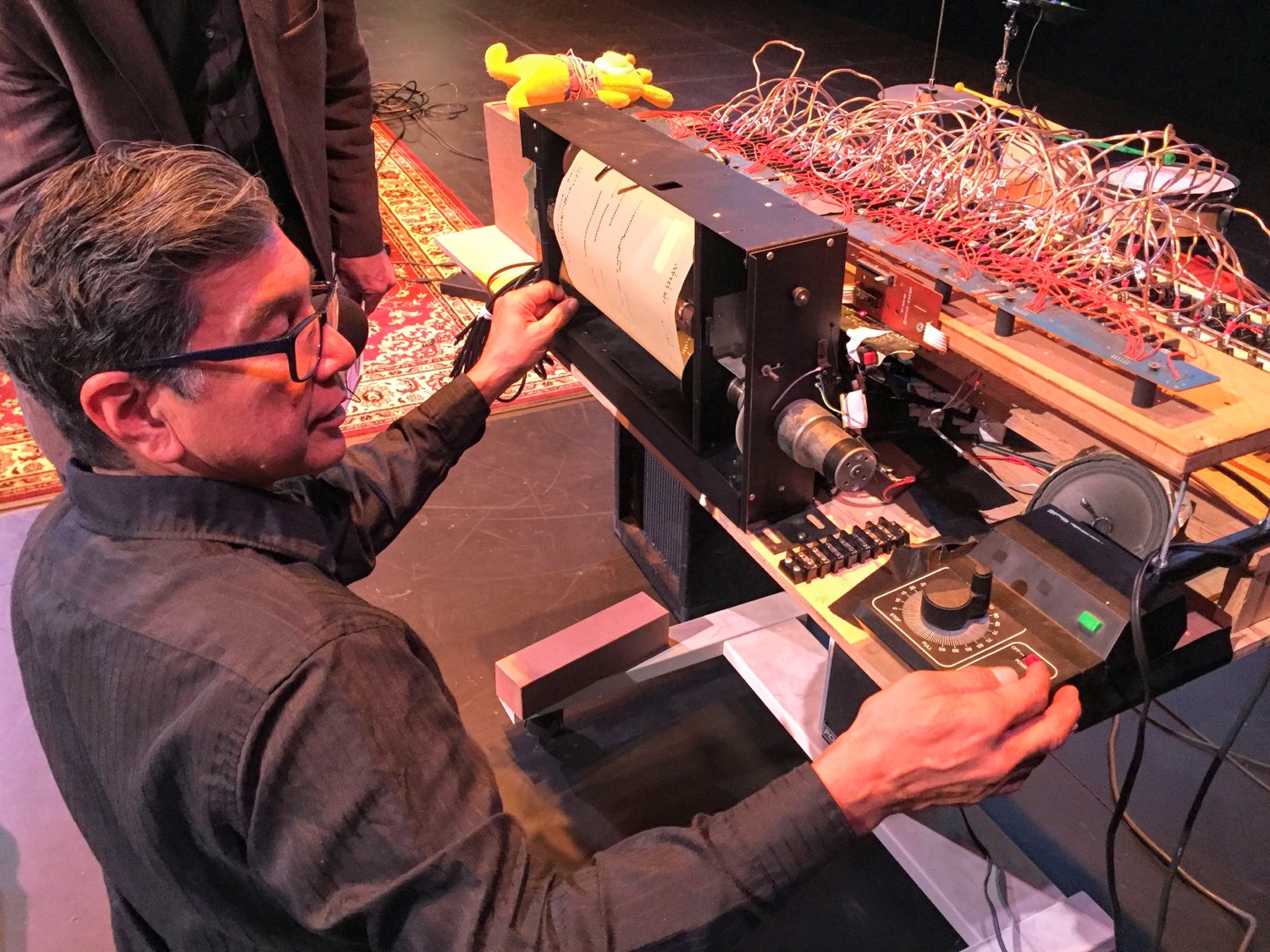

But Nishita has brought the two one step closer with his “Echolodeon.” The custom-built machine converts original piano rolls, created from actual performances by greats like Debussy and Eubey Blake, into MIDI signals routed through modern-day synthesizers.

In this segment, he demonstrates the Echolodeon, talks about how he got his start in music (one source of inspiration was an obscure morse code record his dad gave him), and discusses how playing with sound can teach other fundamental skills.

Mark Ramos Nishita (aka Money Mark) is a musician and maker. He was part of the Beastie Boys, and scored the TV show “Ugly Delicious.” He’s based in Los Angeles, California.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow coming to you from the Civic Arts Plaza in Thousand Oaks, California.

[APPLAUSE]

I’d like you to consider Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 5.

[MUSIC PLAYING – BEETHOVEN, “PIANO SONATA NO. 5”]

This beautiful piece of music may not seem on the face of it to have much to do with technology, but the development of the piano forte, as they called it back then, was a hugely influential techy innovation, allowing pianists to play expressively soft or loud, and to fill a hall with the sounds of the keys.

The innovation, of course, didn’t stop there. For example, Doctor Robert Moog, brought whole orchestras and strange space-age sounds into people’s homes, with the Moog synthesizer, which we have right there on our stage, and we’ll be using it in just a little bit.

And my next guest is a musical innovator in his own right, a tinkerer, and maker, who rips apart keyboards and electronics, and then rebuilds them in brainy new ways and he’s going to show us one of his creations tonight. I know you’ve heard his music before too. He opened up our program today. He scored David Chang’s new TV show, Ugly Delicious. His sounds can be heard on Beck’s single, Where It’s At.

[MUSIC PLAYING – BECK, “WHERE IT’S AT”]

[APPLAUSE]

Yeah. And he was most famously part of the Beastie Boys. Please welcome, you know him as Money Mark. Welcome to Science Friday.

[APPLAUSE]

MONEY MARK: Hello, it’s an honor to be here.

IRA FLATOW: How did you get into this stuff? Music combined with electronics?

MONEY MARK: OK, easy story there. My mother is from a family of musicians and my father was an electronic engineer. And I came out like this.

[LAUGHTER]

IRA FLATOW: So you were born with a soldering iron in your hand–

MONEY MARK: That’s right.

IRA FLATOW: And a keyboard in the other hand. Let’s talk about music and technology, specifically piano rolls, which inspired your latest project. And you brought this machine here tonight, the echolodian, right?

MONEY MARK: That’s what I’m calling it, yes.

IRA FLATOW: And we’re going to hear from it a little bit later. But first, tell us what it does.

MONEY MARK: Well, this is a piano roll. If you don’t know what a piano roll is, it’s a piece of like parchment, paper, and it has holes on it. And a tracker bar, reads the holes, and it’s all pneumatic. There are little hoses and each one of these dots is a note on the piano. And eventually, all that air pressure makes a bellow move. And the hammer will hit the appropriate key.

IRA FLATOW: Better than you talking about it, let’s go show it.

[APPLAUSE]

I’m going to come over here with you.

[PIANO MUSIC]

MONEY MARK: So the piano is on, digital piano. So in this version, I thought that an old piano roll, music that we really can’t hear or listen to without the interface, I thought to make a digital interface for it. So this will read the piano roll and it will play out of that synthesizer, and out of that synthesizer, this beautiful Polly Moog One brand new synthesizer. If you remember Wendy Carlos made this beautiful switched-on Bach, right?

IRA FLATOW: I have that album.

MONEY MARK: Oh, yeah, I have two copies so I can beat juggle with them. So, yeah, let’s turn it on and listen to– this is a roll from Eubie Blake. These were rolls, called reproduction rolls, and they were played by the composers. And so many of these exist–

IRA FLATOW: That you can have George Gershwin actually playing Rhapsody in Blue, and creating the holes in there. And when you replay it, it’s actually how he played it.

MONEY MARK: Exactly, it’s actually a MIDI file, Musical Instrument Digital Interface. So MIDI was invented not in 1979 by Ikutaro Kakehashi and Dave Smith. It was invented by some authors. I don’t even know who the authors are. There were so many people, their minds were put together. And they were coming up with cool and crazy stuff, way back then, 100 years ago.

IRA FLATOW: Speaking of cool, let’s see how it works.

MONEY MARK: OK, so the air pressure, I use a vacuum pump back here. I cheat a little bit there. So now there’s air pressure inside this whole system. There’s valves, a bunch of valves in there. And the holes are going to go by the tracker bar. And it’s going to play through these synthesizers. Let’s hear the piano sound, so we can hear how it kind of just sounds as a piano. Let’s hear it, please.

[PIANO MUSIC]

There we go, see. When the holes go by the tracker bar, it informs this brain. It kind of processes it and sends it into a MIDI cable.

[PIANO MUSIC]

And there’s a little sweep that Eubie Blake did. This is kind of the intro of the song.

[PIANO MUSIC]

Yeah, fun. So now, from here, we can change these sounds. Let’s listen to Eubie Blake playing, how about a Fender Rhodes? How’s that?

[GUITAR MUSIC]

Let’s hear it.

[GUITAR MUSIC]

And that’s the beautiful thing about it, is I can go back and forth with it. Because it’s tactile. I can touch it. Now let’s hear another sound here. How about a wild synthesizer sound, like this?

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Well, that’s not so wild, but let’s listen to it like that.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

It’s going to be beautiful.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

IRA FLATOW: So technically, you can make like Debussy play electronic synthesizer with this thing.

MONEY MARK: Exactly, that’s the point. So my idea was to– let’s fade out here. My idea was to get these rolls, and put them through this machine, and let’s make some new music. And also, let’s make a public space project out of it.

IRA FLATOW: Now this idea of using punched role is not really a brand new idea, is it?

MONEY MARK: No, it really isn’t. Mechanical music goes back a couple hundred years. There were music boxes, beautiful ones. But the punch card idea came from Jacquard, who made a loom, like this rug would have been programmed with punch cards, with holes in these cards. And the cards would be a program of the design that he would create. And that same design can be created over, and over, and over.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s go sit down and talk some more.

[APPLAUSE]

So then you had the punch card that sort of morphed into the piano rolls and into other kinds of things.

MONEY MARK: Yeah, right, and–

IRA FLATOW: And computers and stuff like that.

MONEY MARK: Yeah, hopefully, I can get the crowd to help me find rolls. And I’m going to publish the plans of that machine so people can make them. It’s not very hard to make them. And all my projects are going to be open sourced. And that’s my– I mean, I feel like that’s the only way to go.

[APPLAUSE]

IRA FLATOW: You brought a couple little music toys with you tonight for all the young makers out there.

MONEY MARK: Yes, a couple of things. One that has rhythm and then one that makes a melody. It is super simple.

IRA FLATOW: Show us you got there.

MONEY MARK: My father wanted to be part of my music life, because I was kind of taking after my mom’s family, like becoming a musician. But he was insistent on being involved here. Like, he gave me this record, and it’s like how to code the easy way with the, you know– And I was like, there’s some good beats on this record here. A lot of dots and dashes and dips.

IRA FLATOW: It looks like about 1962 that–

MONEY MARK: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: –cover, and how to play Morse code.

MONEY MARK: So he actually got me a paddle.

IRA FLATOW: So you have Morse code key?

MONEY MARK: If you were into electronics back then, you were really kind of into ham radios too.

IRA FLATOW: Yes, yes.

MONEY MARK: Because they kind of put everything together.

IRA FLATOW: You got a lot of hams in the audience, I can see that.

MONEY MARK: Three people clapping for that.

IRA FLATOW: That’s enough.

MONEY MARK: No, I’m going to hang out with you guys afterwards. So we made this pocket radio. This isn’t the actual radio. But I use this to demo it, because it won’t run out of batteries.

IRA FLATOW: It’s a windup radio.

MONEY MARK: Yeah it’s a wind up radio.

IRA FLATOW: And you have a little Morse code key.

MONEY MARK: And you kind of just have on and off, right here.

[STATIC SOUNDS]

I mean–

IRA FLATOW: Cool.

MONEY MARK: That was my beat machine right there. I was never bored.

IRA FLATOW: You don’t need a fancy instrument.

MONEY MARK: And this microphone that you might just find at a thrift store.

IRA FLATOW: Right, a little microphone, a little battery operated amplifier.

MONEY MARK: One of the great melodies with feedback. And I know Jimmy Hendrix was famous for feedback, right?

[MUSICAL SOUNDS]

IRA FLATOW: It’s like a theramin. It’s almost like a–

MONEY MARK: Yeah, my binary on and off is the switch right here.

[MUSICAL SOUNDS]

IRA FLATOW: That’s cool, that’s cool.

[APPLAUSE]

That’s really cool. I have a question from the audience on this side.

AUDIENCE: How does the beat of music know affect how you act to it?

IRA FLATOW: Whoa, I tell you, the kids ask the best questions.

MONEY MARK: So the question is, how does the beat know, like it has a brain, right? Oh?

IRA FLATOW: How do you how does it control how you react to it?

MONEY MARK: You know, Dr. Moog would say that all of the machines that he created were his friends and it had kind of its own life. And when you interacted with it, you were kind of like with your friend. And the energy that you were putting into it was coming directly back to you. That’s a really cool question. Hmm– That’s an eternal question right there. I’m going to have to put that in my book.

IRA FLATOW: OK, let’s see if we can get–

MONEY MARK: If you want to play the beat machine later, I’ll let you.

IRA FLATOW: That’s a good idea. Yes, [INAUDIBLE].

AUDIENCE: I can’t top that question, but thank you so much, first of all, for your appreciation of sound and your proliferation of the spirit of play with music. I really appreciate that.

MONEY MARK: Thank you.

AUDIENCE: What is your experience, and/or interest, in applying these kinds of things to therapy, especially as it goes for PTSD and chronically traumatized industries?

MONEY MARK: Absolutely. That’s a great question. And I have an amazing answer for that. One of my music heroes was Harold Rhodes. It’s a famous keyboard, the Rhodes piano. Before it became a Fender Rhodes, Harold Rhodes invented that electric piano to do therapy for the soldiers after the war. He was doing piano therapy at his home.

And then he realized it would be easier to put some kind of keyboard in his truck and take it to the person’s home or wherever they were. And that’s how he invented this electric keyboard. And this would be an amazing thing to actually kind of reinstate.

Occasionally I’ll find a broken keyboard in a thrift store and buy it. And I have a dozen or so just waiting in the wings to give to people. I do, I give them to people. And if I see somebody who is kind of wandering, I would just give them a keyboard, say hey, try to mess around with this thing.

IRA FLATOW: That’s great. It’s so great to have a geek like yourself, musical geek, on the program. I’m usually the lonely geek. But I’m very happy to have you on stage with me. Money Mark, a musician, ultimate geek maker, based in Los Angeles. Thank you so much for joining us tonight.

MONEY MARK: [INAUDIBLE] It’s an honor to be here.

IRA FLATOW: After the break, the social lives of bees, ants, and even spiders– “What it Takes to be a Queen.” This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christopher Intagliata was Science Friday’s senior producer. He once served as a prop in an optical illusion and speaks passable Ira Flatowese.