A Young Scientist Uplifts The Needs Of Parkinson’s Patients

17:25 minutes

I heard elders talk about “the shakes,” but I now know that language reflects deep historical inequities that have denied us access to healthcare, knowledge, and research that could help us alleviate burdens and strengthen our health—enough with the shakes!

—Senegal Alfred Mabry, in Cell

Parkinson’s disease is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder in the United States. According to a 2022 study, some 90,000 people a year in the US are diagnosed with Parkinson’s. It’s a progressive disease that worsens over time, producing unintended or uncontrollable movements, such as tremors, stiffness, and difficulty with balance and coordination.

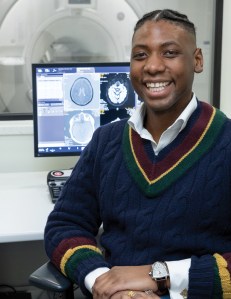

Researchers are working to better understand the causes of the disease, how it connects to other health conditions, and how to slow or prevent its effects. Senegal Alfred Mabry is a third year PhD student in neuroscience at Cornell University, and was recently named a recipient of this year’s Rising Black Scientist Award by Cell Press. His research involves interoception—a sense that allows the body to monitor its own processes—and the autonomic nervous system. He joins Ira to talk about his research into Parkinson’s disease, and the importance of scientific research being connected to communities.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Senegal Alfred Mabry is a 3rd year Ph.D. student in Neuroscience in the Department of Psychology at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Each year an award is presented to promising young Black scientists. In fact, the award is named “The Rising Black Scientist Award.” And one of the winners this year was recognized for his work in understanding Parkinson’s disease.

Parkinson’s, as you may know, is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder in the US. According to a 2022 study, some 90,000 people a year are diagnosed with Parkinson’s. It’s a progressive disease that worsens over time, producing unintended or uncontrollable movements, such as tremors, stiffness, and difficulty with balance and coordination. Researchers are working to better understand the causes of the disease, how it connects to other conditions, and how to slow or prevent its effects.

Senegal Alfred Mabry, a third-year PhD student in neuroscience at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, chose to study Parkinson’s for an additional reason, a social reason. And as I mentioned, Mabry is a recipient of this year’s “Rising Black Scientist Award,” a program created by Cell Press, and he joins me now. Welcome to Science Friday.

SENEGAL ALFRED MABRY: Happy Friday, everyone. Thank you so much for having me on. Yeah, as you’ve mentioned, I’m a third-year doctoral student in human neuroscience. My advisors are Drs. Adam Anderson and Eve De Rosa, and the leaders in the field of emotions and neurochemistry, respectively. And my work examines the heart-brain axis in Parkinson’s disease.

IRA FLATOW: Looking at your biography, though, you weren’t originally a science guy, right? You were a politics and policy guy. What led to the change?

SENEGAL ALFRED MABRY: That’s a great question. I actually have seen myself always science-adjacent or using science, using evidence to help communities really understand the issues that they’re experiencing. In undergraduate, I was lucky enough to have experiences going out to Kenya for a fossil dig looking for miocene era hominids in Rusinga Island. But most of my career path has really been about influencing education policy, helping policy leaders think and redesign education systems.

And during the pandemic, I was working for a major think tank, and I was collaborating with a bunch of current and former US governors across the aisle. And the questions that they wanted answers to, the evidence that they were most interested in using to influence education policy was evidence about the brain, particularly when it comes to early learning. And I said, well, if I’m going to be effective in these spaces, if I’m really going to help leaders make better decisions, I need to get core access and root knowledge to the science.

So I transitioned into a human development program and was interested and passionate about learning how I can grab hold of the science but also communicate and democratize the science for communities and for these policy leaders actually to be able to use to make a difference.

IRA FLATOW: And how big a shift was that, moving into the lab and neurology?

SENEGAL ALFRED MABRY: I think a doctoral program is a challenge for everybody. And everybody has a different conception of what it’s going to be like. My image in my head was going to be kind of Mickey Mouse in Fantasia.

[LAUGHTER]

I don’t know if everybody’s seen that. That classic cartoon where he’s a sorcerer’s apprentice, and he’s playing with magic beyond his control. But he has this distant but brilliant sorcerer there to guide him. I wanted a space where I could make mistakes, where I could learn, where I could fail, but ultimately doing something that would be interesting and meaningful.

And why my advisors really selected me is because I already had an experience working alongside communities, building partnerships between groups, building connections and using evidence. But they took a shot saying, well, he can learn the neuroscience component of this, and he can use his personal experience and the connections that he has to take it in a whole new direction. And that’s what research often is, is trying to understand what’s been done before, but then saying, well, what are the questions that still need answers and who can I work alongside with to get those answers?

IRA FLATOW: But it looks like your motivation is more than just the lab. You write, “I have no Black role models in the scientific field to guide me, but my journey has been defined by resilience, courage, and an unyielding commitment to making a positive impact on my community.” Can you amplify what you’re saying there?

SENEGAL ALFRED MABRY: I think that really starts in going back to Parkinson’s. You know, it’s this disease that encroaches on multiple body systems and parts of our lives. There are innumerable stories in the United States, families who have an experience with this disease, a loved one, a community member, maybe they are caregivers. And a lot of it is about access to knowledge and how we treat and understand and work with disease.

Most obviously, people will recognize it from these motor symptoms, changes in their voluntary motor function, their gait changes. I write in my piece that people call it “the shakes” because of those changes. But right underneath the surface, Ira, you can see how fascinating and diabolical the disease is when I tell you it’s caused by cell death in this tiny subcortical brain region that actually produces the neuromodulator dopamine.

So the same neurochemical that’s really important for reward, and for pleasure, and for exploring our environment, also has a critical role in our motor function. And that’s where you need these MRI tests and these PET tests for people to actually get a diagnosis. And that’s often denied to historically marginalized communities, but also is something that people here in upstate New York are often lacking access to.

And another way this kind of invisible elements of the disease take root is in these cognitive changes, the pattern recognition, the changes in cognitive flexibility, potentially. So all of these are elements of the disease that we aren’t talking about. We’re only talking about the motor changes.

But my hope in the piece was to bring light to the challenges experienced by the Black community in the US around neurodegenerative health, but also spotlight the fact that this country generally needs to have more open and honest conversations about what it means to take care of one another and also to steward brain health for the people who will be diagnosed and the people who have currently been diagnosed.

You mentioned that it’s the second most common neurodegenerative disease in the world. It’s also the fastest rising. So more people are going to be diagnosed with Parkinson’s this year than any other year, and the rates continue to climb.

IRA FLATOW: Do we have the tools, though, yet, or now, to recognize those early symptoms and notice that we’re on the path toward Parkinson’s?

SENEGAL ALFRED MABRY: It’s a great question. And in a lot of cases, yes, we do have the tools, but they’re still in these subspecialized research areas. There’s a great researcher at the NIH, Dr. David Goldstein, who’s doing these positron emission tomography scans, PET scans of the heart, and showing that the heart cell death can occur years before the brain changes for people who are experiencing some additional symptoms– rapid eye movement sleep disorder, for example, or changes in their olfaction, their ability to smell.

So there’s all of these odd elements of the story that when you look at them all together, you can start getting a real package or real understanding of somebody’s risk factors for Parkinson’s disease. And those are the people we can start steering towards resources.

IRA FLATOW: Tell me more about this. Why would symptoms outside of the brain– in your heart, other places– be a clue to about what’s going wrong in the brain in Parkinson’s?

SENEGAL ALFRED MABRY: It’s such an integrated system where there’s not one particular chain. So we’re starting with the motor changes in the disease, yes, but that’s caused by changes in this neurochemical dopamine. So not only is dopamine playing a role in the motor changes but also the cognitive symptoms.

But changes in something like the health of the sympathetic nerves inside the heart could also potentially explain things like orthostatic hypertension. It’s a fancy word for saying low blood pressure when people with Parkinson’s get up from sitting down or lying down. And it’s a symptom that affects 30% of people living with Parkinson’s.

And it’s potentially more debilitating than the general motor gait symptoms because trying to stand up or get up can lead folks to passing out because they’re not recognizing these changes in their low blood pressure. My role, Ira, is really not only to look at the symptoms, but think about how the brain and the autonomic nervous system may actually explain the symptoms.

IRA FLATOW: You can’t look at everything, can you? I mean, you must have to focus on something first in your work. What would that be?

SENEGAL ALFRED MABRY: Well, an example of some of the work that we’re doing is trying to understand interoception in Parkinson’s disease. It’s a funny word. It’s like introspection. It’s similar. And to explain it to folks, I often ask people, how many senses do you have? So Ira, how many senses would you say you have?

IRA FLATOW: Five, six–

SENEGAL ALFRED MABRY: Five?

IRA FLATOW: –seven?

SENEGAL ALFRED MABRY: Most people say– oh, I like this. Yeah, most people say five. And that’s what we’ve been taught in school. And there’s the obvious smell, which we’ve talked about being disrupted. Hearing, vision, touch, and taste are all impacted in Parkinson’s disease, sure.

But now let me just ask you, and your wonderful audience, just to close your eyes for a second, unless you’re driving. Just close your eyes, and try and count your heartbeats. Give it a couple of 30 seconds or so. Just try and count your heartbeats. Breathe out. Don’t touch your pulse points. And try and count them.

IRA FLATOW: It’s not easy to do if you’re not listening carefully to your heartbeat.

SENEGAL ALFRED MABRY: If you were able to catch them, great job. Now tell me what sense you were using to feel those heartbeats, if you were able to grab one.

IRA FLATOW: Well, if I were able to touch my wrists where my pulse is, or if it was really quiet and I could– at nighttime, lying in bed or something, I might be able to hear or feel it.

SENEGAL ALFRED MABRY: Right. So you didn’t smell it. If you tasted it, please go seek help immediately. I don’t know about that. But you did feel it, but it’s this internal feeling.

IRA FLATOW: Right.

SENEGAL ALFRED MABRY: Or similar to a hearing. And so that’s what we call interoception. It’s your body’s internal ledger of what’s happening inside of it. It’s this connection between your brain and your body and how your brain recognizes what’s happening inside of your body.

IRA FLATOW: Right.

SENEGAL ALFRED MABRY: It underlies your emotional health, gives you feedback from that autonomic nervous system. And we’ve been testing it to understand how impairments in interoception in Parkinson’s disease could connect with these other symptoms. And we do that using fancy MRI, otherwise known as functional MRI, to see how the connections between brain regions change while they’re doing an interoceptive task.

We’re still in the early stages of the research, but what’s exciting about the approach that I’ve chosen to take is we get to do this alongside communities, including an exercise intervention that actually has been able to improve folks’ motor and gait outcomes in control studies.

IRA FLATOW: Tell me about that. What do you mean?

SENEGAL ALFRED MABRY: So I started this journey interested in the heart-brain axis in Parkinson’s disease. And I didn’t just file for my IRB and start collecting data from patients. I went out to the support groups in the southern tier area, in the Finger Lakes area and the Tompkins County area.

And they said, all that stuff is great and we’re happy you’re trying to capture these root elements of the disease, but what are you actually going to do for us in the interim? How is this going to have an immediate benefit? How are you going to live up to these translational ideas that you’ve come in and you’ve talked about?

And they gave me suggestions. They gave me people to talk to. And one of them was a Dr. Jeff Bower at SUNY Cortland who had been running this exercise study on a high intensity exercise intervention usually used by these Olympic skiers. It’s called a react trainer. It’s this platform where people with Parkinson’s can just safely balance on an oscillating platform that moves underneath them. And they get a heck of a cardiovascular workout. And it’s been able to improve their motor and gait symptoms.

But there’s so much that’s unknown about how the training of the autonomic nervous system, which is really what exercise is, why it improves motor and gait symptoms for Parkinson’s disease. Even though people living with Parkinson’s are really passionate about exercise– there are the Rock Steady Boxing programs. Dance is an incredible intervention for people living with Parkinson’s, in part because it helps build intentionality around movements.

But we don’t have clear answers around how the brain and the autonomic nervous system are connected from exercise. And so we’ve been able to take people and do a pre- and post-study for this exercise intervention and ask questions not only about their interoceptive ability, these autonomic nervous system changes, but hopefully gather real evidence about how it actually works, so that we can tune it, and we can improve it.

And that’s the type of rigor and excellence you can get when you take a community approach to your research rather than saying, I’m just going to release this study. But thinking, well, who are the main actors really involved in my community, and what are the areas of interest that the stakeholders that I have, the people that I’m doing the research on behalf of, are passionate about?

And I think that’s what you can only get when you’re training to be a community neuroscientist, when you’ve come in from a policy or an impact background, and now you’re saying, well, how do I use science, how do I understand and then grab hold of the tools to actually be able to make impact in my community?

IRA FLATOW: Well, you sound like a very passionate person yourself. Is this a topic you’re likely to continue down the road once you complete your PhD? Where do you see yourself headed?

SENEGAL ALFRED MABRY: I think I’m passionate about this– again, everybody has a story around the disease. Mine begins– I was training on my amazing postdoc study, Dr. Elizabeth Riley’s large study on Alzheimer’s disease. And we were collecting data from a really diverse set of participants, Black people from Syracuse who we were able to win a partnership to bus out to Ithaca and do a study about their brain health.

And I met an older woman who was funny. She was attentive. She was a local gossip. She knew everybody and their mother’s business. And she had a resting tremor in her right hand, a telltale symptom. And when we gave her all of our cognitive tests, she just flunked every single one of them. And it didn’t represent the extremely resilient person that was in front of me. So I started on this, interested in how do we bring what we know from psychology research or from all of these places to honor and recognize this person’s resilience?

And so I think being in partnership with the Parkinson’s community and being a place where those stories come, and then trying to do really rigorous research to honor those stories and provide evidence to explain why those are the case and help people feel seen is what I want to do. I think you can do that best from a research seat because you’re often the ones in charge of or the ones stewarding, grabbing evidence, and generating evidence, and helping people understand the landscape.

IRA FLATOW: Well, Senegal, I am impressed with your drive and your energy and your motivation. And congratulations on your award. And I look forward to hearing from you in the future.

SENEGAL ALFRED MABRY: Hey, thank you so much for having me on.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you for taking time to be with us today. Senegal Alfred Mabry is a third-year PhD student in neuroscience at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, and recently named a recipient of this year’s “Rising Black Scientist Award.”

Copyright © 2023 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Shoshannah Buxbaum is a producer for Science Friday. She’s particularly drawn to stories about health, psychology, and the environment. She’s a proud New Jersey native and will happily share her opinions on why the state is deserving of a little more love.

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.