Remembering Roger Payne, Who Helped Save The Whales

34:41 minutes

Americans haven’t always loved whales and dolphins. In the 1950s, the average American thought of whales as the floating raw materials for margarine, animal feed, and fertilizer—if they thought about whales at all. But twenty-five years later, things changed for cetaceans in a big way. Whales became the poster-animal for a new environmental movement, and cries of “save the whales!” echoed from the halls of government to the whaling grounds of the Pacific. What happened?

Shifting attitudes were due, in large part, to the work of scientist Roger Payne, who died earlier this month at the age of 88. His recordings helped to popularize whalesong, and stoked the public imagination about intelligent underwater creatures who used vocalizations to communicate.

In 2018, our podcast “Undiscovered” explored the history of Payne’s work, and that of his colleagues. We’re featuring this episode as a way of remembering his life and groundbreaking work.

D. Graham Burnett is a professor of history at Princeton University and author of The Sounding of the Whale: Science and Cetaceans in the 20th Century.

Scott McVay is former executive director of the Robert Sterling Clark Foundation, Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation, and the author of Surprise Encounters.

Roger Payne was a biologist and author of Among Whales.

Sheri Wells-Jensen is a linguist and associate professor of English at the Bowling Green State University in Bowling Green, Ohio.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. There are only a few scientists whose work can be directly linked to the preservation of a species. Well, one such scientist died earlier this month. I’m talking about Roger Payne, the man who brought the songs of the humpback whale to the public consciousness.

Payne died at his home in Vermont at the age of 88 after spending a career dedicated to researching the symphony of sounds whales make to call to each other. These songs became a wake up call to humans, who began to see whales and dolphins very differently than they had throughout history.

Iceland, Norway, and Japan are the only countries in the world that still permit whaling. This week, Iceland’s government said it will suspend this year’s fin whale hunting until the end of August, due to animal welfare concerns, a move some hope will lead to the end of commercial whaling there.

Back in 2018, our podcast, Undiscovered, looked at the impact of Payne’s work and that of his colleagues. And we wanted to bring you that story as a way of remembering his life. Here’s our hosts, Annie Minoff and Elah Feder.

[CHATTER]

SPEAKER: Oh, wow, look at those fins.

ANNIE MINOFF: Every year, 13 million people go out on to the water to watch whales and dolphins– just watch them. Those are a few of those people. That’s a boat full of whale watchers in Baja. And chances are they paid good money to do this.

We spend $2 billion a year to watch whales and dolphins, like 2 billion– billion, with a B– which might seem a little excessive, like a little over the top. Except it turns out everything about our love for whales and dolphins is just a little bit over the top. We’ve got the t-shirts–

ELAH FEDER: Sure.

ANNIE MINOFF: –with the leaping turquoise dolphins on the front.

ELAH FEDER: The sunset in the background.

ANNIE MINOFF: Exactly. We listen to albums of whale song. And if we get a chance to touch– you know, actually pet a whale’s barnacle-encrusted snout, we just lose it.

SPEAKER: Yes. Aw. Oh, boy.

SPEAKER: Oh, great.

SPEAKER: Oh, boy.

ELAH FEDER: Yeah, that guy did.

SPEAKER: Yes.

ELAH FEDER: I have to say, if I heard that sound out of context, I’m not sure I would have figured out it was about a guy petting a whale.

ANNIE MINOFF: [GASPS] I had to think about that. Yeah, OK. Anyway, we love whales and dolphins–

ELAH FEDER: Yes, clearly.

ANNIE MINOFF: –so much, it’s actually hard for us to imagine ever not feeling this way.

ELAH FEDER: Except that we did. We felt very differently about these animals not that long ago. This guy, Roger Payne, he remembers it. And he remembers specifically what happened one March afternoon in the mid-’60s.

ROGER PAYNE: Yes, I was teaching at Tufts University. And I was–

ELAH FEDER: Roger was an assistant professor in biology. And one day, he’s working in his lab–

ROGER PAYNE: And I heard over just the local radio station, Oh, there’s a whale washed ashore on Revere Beach. And I thought, Oh, great, I’ve never seen a whale. I’d love to go see one.

ELAH FEDER: So Roger jumps in his car. But by the time he gets to the beach, the sun’s already set. It’s dark out. It’s raining hard. All of the other whale-gawkers have gone home. So it’s just Roger out there, and he’s scanning the beach with his flashlight.

ROGER PAYNE: And I walked around the beach and found the whale. And it wasn’t a whale. It was a dolphin.

ELAH FEDER: Roger points out that dolphins are technically whales. It’s just not the kind of whale that we usually think about. They’re cetaceans, full-time aquatic mammals, just like sperm whales, blue whales, and porpoises. And anyway, Roger isn’t splitting hairs at this point. In this moment, he’s just focused on what people had done to this dolphin.

ROGER PAYNE: Somebody had carved their initials in the flank of this dolphin. Someone else had cut off its tail, and the tail was missing. Somebody else had stuffed a cigar butt in the blowhole of this dolphin. And I just– I was just overwhelmingly shocked and depressed by the thought that this seems to be what happens when humans encounter these animals.

ELAH FEDER: Roger stood there for a long time. He stood there so long that his flashlight battery gave out.

ROGER PAYNE: There was a source of lights in the distance. And I could see the silhouette of the curves– the glistening curves– of this beautiful creature. And thought to myself, god, there’s got to be something different in how people deal with these animals when they encounter them.

ANNIE MINOFF: Roger didn’t know it then, but things were about to be very, very different for whales and dolphins. In a little over a decade, we’d go from thinking, like, maybe it’s OK to stick my cigar butt in this animal’s blowhole to this.

[CHATTER]

[KISS]

SPEAKER: I did it again.

SPEAKER: All right.

[LAUGHTER]

ELAH FEDER: Is she kissing that whale?

ANNIE MINOFF: Yeah.

ELAH FEDER: OK.

ANNIE MINOFF: And this transformation would happen in very large part because of one scientific discovery.

ELAH FEDER: So it’s about the mid-’60s, and Roger decides he’s going to do something for whales. But what exactly Roger can do– not totally clear, at least not from the outside. Roger doesn’t have a lot of activism experience. And he doesn’t even study cetaceans. He studies sound, how animals make it, use it, hear it. He’s looked at bats and owls. But at this point in his career, he’s all about–

ROGER PAYNE: Moths.

ELAH FEDER: –moths.

ROGER PAYNE: How they avoid bats by hearing the direction from which a bat is coming.

ELAH FEDER: Not really clear how a moth expert is going to save the whales.

ANNIE MINOFF: But Roger’s got a bigger problem, and that is how much most people in ’60s America just do not care about whales. 100 years ago, the Moby-Dick era, whales were monsters. They were feared and respected. By the ’60s, they’re just commodities.

D. GRAHAM BURNETT: Which, as it turns out, they do serve pretty well as industrial commodities.

ANNIE MINOFF: That’s historian D. Graham Burnett. He wrote a book called, The Sounding of the Whale, about the history of whale science. Graham says, by the ’60s, whales were being transformed into just a dizzying array of truly disgusting industrial products, stuff like–

D. GRAHAM BURNETT: Granulated bone meal.

ANNIE MINOFF: Which was a fertilizer.

D. GRAHAM BURNETT: Desiccated meat gravel.

ANNIE MINOFF: Which was a cheap feed for chickens. But he says the real money was in something else.

D. GRAHAM BURNETT: By far, the highest dollar value was actually– ready yourself– margarine.

ANNIE MINOFF: In mid-century Europe, you cannot believe it’s not butter. And you really don’t want to know that it’s hydrogenated whale oil.

ELAH FEDER: Yuck.

ANNIE MINOFF: And by 1963, whales are being turned into butter at a rate that is making even whalers nervous. Scientists are reporting that there may be as few as 650 blue whales left in the entire Antarctic.

[CONTEMPLATIVE PIANO MUSIC]

And there aren’t that many more humpbacks. For whales, things are looking really bad. For Dolphins, less so. Although, hundreds of thousands are dying every year in tuna nets.

But there was actually one group of people around this time who did care about dolphins and whales. And they cared quite a lot, actually, because they had to.

[WHALE CALLS]

And those people were the US Navy.

SPEAKER: Reel number nine– reel number nine. Were playing humpbacks. Today’s the 6th of February 1967. It’s a continuation–

ANNIE MINOFF: So in the ’50s and ’60s, the US Navy, they are compiling this gigantic catalog of underwater animal sounds. Like, you’ve got Navy researchers headed out with underwater microphones. They’re recording whales and dolphins and snapping shrimp–

[RATTLING]

–and sea robins–

[THUMPING]

–and spot fish. This is my favorite one because you got to wait for it.

[VIBRATION]

And they’re doing this for one very good reason.

D. GRAHAM BURNETT: There were Soviet submarines in those oceans.

[RADAR BEEPING]

And you wanted to know when one of those was passing by. And that meant you had to be able to hear it.

ANNIE MINOFF: I mean, this was the Cold War. If you could not tell a moaning whale from a Russian submarine, you were screwed. And so the Navy engineers were listening to these whale tapes. It’s not like they’re having an aesthetic experience.

ELAH FEDER: Yeah, they’re not doing it for fun.

ANNIE MINOFF: Right. Like, I think, today we’re kind of primed to hear these sounds and think, like, calming nature CD–

ELAH FEDER: Mhm.

ANNIE MINOFF: –spa muzak. But Graham says, the guys who are listening to these tapes, that’s not how they were hearing them.

D. GRAHAM BURNETT: Nobody thought of it as song. Nobody thought of it as music. People thought of it as noise.

ELAH FEDER: But to Roger, this was interesting noise. A few years before he saw that dead dolphin on the beach, he’d actually heard some of the Navy’s whale recordings. And he thought, maybe there’s something that I, animal sound expert, can do for these animals because I can study these sounds.

At that point, it was just an idea, something he was thinking about, not something he acted on. But after he sees this dead dolphin, he comes back to it, and he decides to go searching for more of these whale recordings and ends up finding the mother lode in the collection of one Navy sonar engineer. He still remembers the day that this engineer hands him a pair of headphones, threads this tape onto a tape machine, and calls out–

ROGER PAYNE: (MIMICKING ELDERLY VOICE) I think it’s a humpback whale.

[WHALE MOANS AND THUMPING]

The sounds that I heard were absolutely transforming. They were shocking. I had never heard any animal make any sound even approximately as intriguing and commanding. It was incredible.

ELAH FEDER: Roger grew up listening to classical music. He’s a pretty serious amateur cellist, plays a lot of chamber music. He thinks maybe that played into his reaction. But for whatever reason, when Roger heard these sounds, he didn’t hear noise, like the Navy did. He heard music. And to hear Roger tell it, this is the moment he has the idea.

ROGER PAYNE: You know, if we could get humanity to hear these sounds, we could get them interested in whales probably enough to do something about it.

[WHALE CALLS]

ELAH FEDER: He thought, this sound, this is how we save the whales. Except he didn’t actually know what that sound was. As a music lover, Roger was intrigued by the musicality of it. As a scientist, he is stumped. He has no clue.

ANNIE MINOFF: Roger estimates it’d been about a year since he saw that dead dolphin on the beach. It was 1967. 64,000 whales died that year. That’s an average of one whale every 8 minutes. So this is what Roger is up against. This is what he’s trying to stop. And all he has is this tape.

[UPBEAT ELECTRONIC MUSIC]

But Roger is about to have something else. Roger is about to have an ally, an unconventional scientist who’d spent two years of his life trying to teach dolphins how to speak English–

[DOLPHIN CALLS]

–and cultivating a truly fantastic dolphin impression.

[SLURPING]

And together, this scientific odd couple were about to make whale history.

IRA FLATOW: You’re listening to a story from our podcast, Undiscovered, from 2018, about the late Roger Payne, one of the scientists who changed the way we think about whales and dolphins. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios.

ANNIE MINOFF: The guy that Roger was about to team up with to save the whales, his name was Scott McVay. And Scott is not your typical scientist. He writes poetry. He’s a very proud English major. But even though he didn’t have the formal scientific credentials, back in the ’60s, Scott was most definitely doing science.

SCOTT MCVAY: Well, I was privileged to be working with a dolphin, named Elvar.

[DOLPHIN CALLS]

And it was my privilege to work with Elvar six days a week, morning and afternoon.

ANNIE MINOFF: Scott was a researcher at something called the Communication Research Institute in Miami. This was a dolphin lab set up in an old bank building, of all places.

ELAH FEDER: OK.

ANNIE MINOFF: So I’m, like, imagining the vaults and the dolphin tanks next to them. There were seven dolphins, who they all lived in this old bank. And Elvar was one of them.

SCOTT MCVAY: He was the most precocious of these seven and maybe the most precocious dolphin we know of.

ANNIE MINOFF: And this turned out to be pretty lucky because Scott’s job was to try to teach Elvar to speak English. Scott’s boss at the Communication Research Institute was this guy, big shot, brain scientist, named John C. Lilly.

[BOUNCY SYNTH MUSIC]

And by the early ’60s, Dr. Lilly had come to a few conclusions about dolphins– A, that dolphins are super intelligent, B, they probably have their own language, and C– this is, like, the big one– they’re actively trying to communicate with us. They’re actually bending the air coming out of their blowholes, trying to make sounds like English words.

And Dr. Lilly felt that we could actually help the dolphins along, like we could eventually teach them to communicate in our language.

ELAH FEDER: Right, it would help to have an instructor when you’re learning English.

[LAUGHTER]

Why not humans?

ANNIE MINOFF: And Scott McVay, he’s fascinated by all of this.

ELAH FEDER: I would want to do this.

ANNIE MINOFF: I mean, who wouldn’t want to do this, right? He actually quits– he has this stable job as an administrator at Princeton University, quits that job, moves his entire family down to Miami to work on this project, to teach dolphins English. Except, like, how do you–

ELAH FEDER: Yeah where do you start? Grammar? Gerunds?

[LAUGHTER]

I don’t know.

ANNIE MINOFF: Well, they started this way. So Scott would stand next to Elvar’s dolphin tank. And he would read off this list of random sounds. These are consonant-vowel combinations. It sounded like this.

SCOTT MCVAY: “Ee’s,” “oo’s,” “or,” and he would come back with–

[DOLPHIN CALLS]

“Za,” “is.”

[DOLPHIN CALLS]

“Nee,” “are,” “ight,” “ra,” “row,” “oh.”

[DOLPHIN CALLS]

He would give a response, and I’d give him a butterfish. And then at the very end of the session, I would say, in falsetto voice to push it up a little bit, I would say the name of the institute. I would say, Communication Research Institute. And Elvar [CHUCKLES] came back, going [MIMICKING DOLPHIN WHINE].

Anyway, that’s a bastardization of the beautiful thing he was trying to do.

ANNIE MINOFF: In retrospect, this can sound a little far-fetched. But for Scott, this was really important. Dolphins suggested an answer to this very profound problem.

SCOTT MCVAY: The long loneliness.

ANNIE MINOFF: The long loneliness– this wasn’t a term that Scott came up with. It’s actually the title of an essay by the science writer, Loren Eiseley. And Eiseley had written–

SCOTT MCVAY: That, as children, we talk to animals, typically dogs and cats. They’re the most likely critters. And they don’t seem to be answering. And eventually, we stop talking.

ANNIE MINOFF: It’s like we try to have this back-and-forth with the animals in our lives, and it doesn’t really seem to be going anywhere. And we basically conclude, like, we’re never going to have a back and forth conversation with another species.

SCOTT MCVAY: And he said that we have been in this long loneliness for a long time. And now, perhaps, finally there may be a chance to communicate with another species– interspecies communication.

[CONTEMPLATIVE ELECTRONIC MUSIC]

IRA FLATOW: That’s whale conservationist, Scott McVay, speaking to our podcast, Undiscovered, back in 2018. We’re bringing you his story and that of his colleague, Roger Payne, on today’s program. And we will be right back after this short break.

This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. We’re continuing our story about humans learning how to communicate with cetaceans, animals like whales and dolphins, and how capturing their vocalizations led to a worldwide effort to save the whales. Reporters Annie Minoff and Elah Feder reported this story for us back in 2018 on our podcast, Undiscovered.

They focused on the work of Scott McVay and Roger Payne. Payne had started his career researching moths before he turned his attention to the sea. He died earlier this month at the age of 88. Here’s Annie.

[CONTEMPLATIVE ELECTRONIC MUSIC]

ANNIE MINOFF: Roger Payne, the moth man, he got interested in cetaceans because he wanted to save them. But Scott McVay, he wanted to break through. He wanted a meeting of the minds. And that’s why a few years before Roger stands on that beach with the mutilated dolphin, Scott is already standing by Elvar’s dolphin tank doing this.

SCOTT MCVAY: [RECITING ENGLISH SOUNDS]

[DOLPHIN CALLS]

ANNIE MINOFF: And it’s why he spends even longer analyzing the sounds that Elvar is making, which he does using a technology that’s still, like, pretty cutting edge at the time.

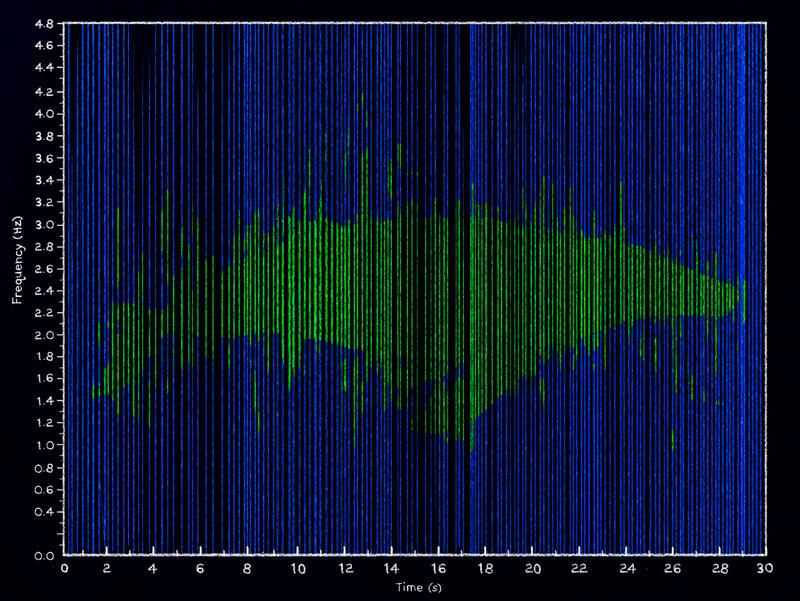

D. GRAHAM BURNETT: We’re talking about sound spectrographs.

ANNIE MINOFF: Historian Graham Burnett, again.

D. GRAHAM BURNETT: A kind of representation of sound that’s familiar to everybody who mucks around with GarageBand, but at the time was still very exciting. You could see sound.

[LIGHTLY SHUFFLING MUSIC]

ANNIE MINOFF: You could feed a sound into the spectrograph machine, and the stylus would etch out the frequencies onto this roll of paper.

ELAH FEDER: It’s sound in, squiggles out.

ANNIE MINOFF: The idea being, you might notice things in those scribbles, like patterns, complexities that your ears wouldn’t hear. And Scott pored over these scrolls. He’s looking. He’s trying to do what his boss wants him to do, which is find the, “ee’s,” “oo’s,” “or,” syllables.

ELAH FEDER: See if dolphins are, yeah, doing the English syllables.

ANNIE MINOFF: Exactly. But he’s also looking at something else. So Elvar spent a lot of time seemingly chatting back and forth with this other dolphin, named Chi-Chi, sound a little bit like this.

[DOLPHIN SQUEALS AND VIBRATIONS]

ANNIE MINOFF: And Scott, he’s eavesdropping on that too. He’s trying to figure out, what is that back-and-forth? Is that dolphin language? But he doesn’t get that far because about two years after Scott joins the dolphin lab, it’s starting to implode. And the problem is his boss, Dr. John C. Lilly.

I mean, on the one hand, Lilly is doing a fantastic job promoting dolphins, like he’s killing it. He’s writing about talking dolphins in Life magazine. He’s going on late night. He’s a large part of the reason you could turn on a TV by the 1970s and hear a reporter say something like this.

SPEAKER: These animals, small whales known as dolphins, may be second in intelligence on this planet only to man. They have a complex language we have been unable to crack. Although, they obviously understand us.

ANNIE MINOFF: Lilly is great at getting people really excited about dolphins. But his scientific results aren’t exactly living up to the hype. He’s not publishing a lot, possibly because he’s dropping a lot of acid.

[LAUGHTER]

ELAH FEDER: That would not help.

ANNIE MINOFF: It was the ’60s.

ELAH FEDER: Maybe it would help– I mean, the creative process, not the follow through.

ANNIE MINOFF: The lab’s funders are understandably getting a little short on patience. But the real tragedy for Scott is what happens in 1965. Elvar the dolphin dies of pneumonia.

ELAH FEDER: [SIGHS]

ANNIE MINOFF: And Scott is heartbroken. He moves home to Princeton, gets another University admin job, and it kind of seems like that’s it. You know, no more dolphins. No more “ee’s,” “oo’s,” “or.” A few years pass. The long loneliness stretches on until Scott hears this.

[WHALE CALLS AND VIBRATIONS]

ELAH FEDER: That was moth Prof. Roger Payne’s beloved whale tape. This is the one he thought might save the whales. Roger had actually read an article of Scott’s in Scientific American. These two cetacean lovers, they start chatting. And pretty soon, Roger lends Scott his tape.

ANNIE MINOFF: And when Scott hears these sounds, he’s hooked exactly like Roger. And after those years in the dolphin lab, he knows what you do with a long tape of cetacean sounds. You feed them into a spectrograph machine– sound in, squiggles out.

SCOTT MCVAY: It turns out that on the Princeton campus, there’s only one sound spectrograph.

ANNIE MINOFF: Scott found it in the basement in this Princeton professor’s bird lab. And he convinces the guy to let him use the machine on nights and weekends. And pretty soon, Scott’s running off thousands of these paper strips, just strip after strip of whale sound.

SCOTT MCVAY: Laying them out, looking them over.

ANNIE MINOFF: Just like he’d done with Elvar’s sounds.

SCOTT MCVAY: And at first, this just seems like a cacophony of sounds.

ANNIE MINOFF: But then he sees it.

SCOTT MCVAY: Suddenly, you just get it.

ANNIE MINOFF: These sounds are not random. There’s a pattern here.

ELAH FEDER: So Scott takes his spectrograms to Roger to show him what he’s seen, show him there is a pattern in these scrolls. And Roger does not need convincing. He says he’d heard this pattern. Now he could see it. And it worked like this. You start with a unit.

ROGER PAYNE: A unit is a sound which is continuous to your ear. So “whoop,” that would be a unit.

ELAH FEDER: You string a few of those units together–

ROGER PAYNE: “Whoop,” “bom,” “bom,” that would be what’s called a phrase.

ELAH FEDER: String a few of those phrases together–

ROGER PAYNE: “Whoop,” “bom,” “bom.” “Whoop,” “bom,” “bom.”

ELAH FEDER: –now you’ve got a theme. And what Roger and Scott saw on those strips of paper is that those themes repeat. A whale would do theme A, theme B, theme C. And then a little while later, he’d do it again, theme A, theme B, theme C. And that is a really big deal because–

ROGER PAYNE: When any animal repeats itself in a rhythmic way, it is said to be singing, whether it is a cricket or a frog or a bird or a bat or a whale.

ELAH FEDER: That repetition, the fact that these themes are repeating in the exact same pattern over and over again, that meant that these sounds met some biologists’ definition of song.

[WHALE CALLS]

And in a time where whaling nations are killing over 55,000 of these animals a year, that little bit of semantics matters. These animals that we’re killing for granulated bone meal and desiccated meat gravel and butter, these animals are singing.

The first time that Roger Payne had heard the whale tape, he thought, if I could just get people to listen to these sounds, things would change for whales. Now he saw his chance to make the world listen because he had whale song. And he was going to promote the hell out of it. He was going to worm it into pop culture, whatever way he could. And that’s exactly what he did. He goes on TV. He gives interviews about whale song.

ROGER PAYNE: The sounds of some species may travel for a good many miles underwater. Under special circumstances–

ELAH FEDER: Roger gets his whale tape to the New York Philharmonic and convinces the orchestra to jam with his whales.

SPEAKER: Dr. Payne’s whale songs are now part of a concerto called, “And God Created Great Whales,” played this week for the first time by the New York Philharmonic.

[SYMPHONIC MUSIC AND WHALE CALLS]

ELAH FEDER: Roger tries to recruit pop stars to the cause, and he succeeds through sheer moxie– like Judy Collins, famous folk singer. He goes to one of her performances, finagles his way backstage, and hands her– like he’s handing a demo tape– like, he gives her his whale tape. And in 1970, the world gets this.

[JUDY COLLINS, “FAREWELL TO TARWATHIE”] Farewell to Tarwathie. Adieu Mormond Hill. And the dear land of Crimmond, I bid you farewell.

ELAH FEDER: That’s Judy Collins duetting with a whale on her hit record whales and nightingales. Why are you laughing?

ANNIE MINOFF: That’s your FM voice?

ELAH FEDER: Yeah. The whale tape that she’s singing along to is one of Roger’s.

JUDY COLLINS: (SINGING) In hopes to find riches in hunting the whale.

[WHALE CALLS]

ELAH FEDER: Roger even puts out his own record of whale songs, calls it Songs of the Humpback Whale.

ANNIE MINOFF: Descriptive.

ELAH FEDER: And Roger’s record is a sleeper hit. It becomes the best-selling natural sounds album of all time.

ANNIE MINOFF: And people are not just chilling with this record at home, right? This isn’t your “nature sounds for insomniacs” record. They’re taking these sounds to the front lines in the battle to save the whales. Case in point, in 1975, this band of activists from Vancouver, calling themselves Greenpeace, head out into the Pacific to intercept Soviet whaling ships.

SPEAKER: OK, all hands on deck!

SPEAKER: 1-2-3-4-5 over there. There’s one by the Vostok, and there’s three over here. There’s nine chasers all together.

ANNIE MINOFF: On June 27th, Greenpeace spots one of these Soviet whaling ships. It’s this hulking vessel, called the Vostok. And the Greenpeace boat, it pulls up alongside this ship. And the activists start speaking to the Soviet crew through the set of loudspeakers. They’re pleading with them to stop whaling.

SPEAKER: Hello, Vostok. We are Canadian.

SPEAKER: [SPEAKING RUSSIAN]

SPEAKER: We don’t want you to kill the whales. Why must you do it?

ANNIE MINOFF: And the other thing these Greenpeace activists are doing, they’re blasting Roger’s whale record.

[WHALE CALLS]

Hours later, this confrontation comes to a head. The whalers shoot a harpoon straight over this tiny, inflatable Greenpeace boat that the protesters had been maneuvering between the harpoon and the whale. The harpoon flies over the activists heads just 15 feet above them, hits the whale.

Footage of this airs on news stations across North America. And by now it was clear something had shifted. Like, 10 years earlier, most people had not cared about whales. And now activists were literally shielding these animals with their bodies. And anyone who watch the evening news knew about it.

SPEAKER: We must begin to have respect for other life, for comrade dolphin and comrade whale, because without them, the oceans begin to die. And if the oceans begin to die, we all begin to die.

[BOUNCY ACOUSTIC MUSIC]

ANNIE MINOFF: It would take another decade of international haggling, but by the mid ’80s, commercial whaling was a shadow of its former self.

IRA FLATOW: You’re listening to a story from our podcast, Undiscovered, from 2018, about the late Roger Payne, one of the scientists who changed the way we think about whales and dolphins by popularizing whale song. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios.

ANNIE MINOFF: Did whale song [CHUCKLES] save the whales?

D. GRAHAM BURNETT: I would say, whale song did save the whales.

ANNIE MINOFF: Historian Graham Burnett.

D. GRAHAM BURNETT: In other words, it turns out that there is a powerful line between people’s ears and their brains.

[WHALE CALLS]

These sounds, received as musical expression, wormed their way into the mind-hearts of listeners and created that powerful sense of social coordination that can only be achieved in the kind of rhythmic and melodic structures of music.

ANNIE MINOFF: An anthem.

D. GRAHAM BURNETT: An anthem but– yes, an anthem.

ELAH FEDER: Roger Payne thought, if people could just hear these sounds and understand them as song, they’d think about these animals differently. They wouldn’t think of them as monsters or butter or fertilizer, but as a species like us, one that’s worth saving. And he was totally right. Song worked, amazingly.

Today some whale species are still struggling. There are a few populations that are even at risk of extinction, like the northern right whales. But a lot are coming back, especially humpbacks, the whales on Roger’s record. Roger Payne, for the most part, anyway, he got what he wanted.

ANNIE MINOFF: But Scott McVay, Scott wrote something in his memoir that, frankly, surprised me. He wrote that after he discovered the pattern in the whale song, he felt depressed.

Why did you feel depressed by it?

SCOTT MCVAY: Well, because even Caruso singing on a stage is interesting for a long time, but not forever. What I was hoping for was something that was back and forth, back and forth– a conversation.

ANNIE MINOFF: Whale song changed the game for whales. But it didn’t end the long loneliness. We still don’t have a back-and-forth with whales, or dolphins, for that matter, not in the way that Dr. Lilly thought we would. So the thing that Scott had been hoping for to break through to another species hasn’t really happened.

And that’s basically where Roger and Scott’s story ends, or at least that’s where we’re going to leave them. But before we go–

ELAH FEDER: Hm?

ANNIE MINOFF: Before you write off talking dolphins completely–

ELAH FEDER: [LAUGHS] A footnote.

ANNIE MINOFF: –a footnote because it turns out there is something pretty interesting about all those clicks and whistles that Scott was listening to. And it has to do with how complex those sounds are. So if you just forget dolphins for a second, like look at a human language, like English, if I want to put a number to how complex English is, one thing that I could do is I could take a chunk of spoken English, and I could graph out how often every sound in that chunk occurs.

SHERI WELLS-JENSEN: And then you math– math, math, math, math, math. Math happens.

ANNIE MINOFF: That’s Sheri Wells-Jensen. She’s a linguist at Bowling Green State University.

SHERI WELLS-JENSEN: And you get a certain curve, right? You get a certain kind of line.

ANNIE MINOFF: That line is one measure of how complex a language is. And what linguists have known for a long time is that if you look at a human language– doesn’t really matter which one. It could be English or Hindi or Japanese. That line basically looks the same. It has that same baseline complexity.

But then in the ’90s, Sheri says these scientists did something really interesting. They started looking at animals. And they wanted to know, is there an animal out there that has the same line as human language? And at first, it seems like maybe not. You know, they look at squirrel monkey communication.

[SQUIRREL MONKEY SQUEAKING]

Not complex. And in fact, they look at human baby communication, like human baby babbling.

ELAH FEDER: Mhm.

ANNIE MINOFF: That line doesn’t look like the line for adult language.

[BABY BABBLING]

SHERI WELLS-JENSEN: So you’re like, OK, animals don’t seem to have this. Babies don’t seem to have this. And then here comes the big– here comes the fun part. You look at dolphin communication, and it has it.

[DOLPHIN CALLS AND VIBRATIONS]

It’s as complex. And when I first heard that, cold shivers just went down my spine.

[CONTEMPLATIVE PIANO MUSIC]

ANNIE MINOFF: Dolphins, they have this telltale complexity that even human babies don’t have. And that doesn’t tell us what they’re saying– it doesn’t give us a way in– but it’s just one more reason to think that this work that Roger and Scott started, it is so far from over. There are secrets in whale and dolphin sounds. There’s complexity there. We’re lonely now, but we might not be lonely forever.

IRA FLATOW: That story comes from our podcast, Undiscovered, and was reported back in 2018. Annie Minoff and Elah Feder were the producers and hosts, and it was edited by Christopher Intagliata. D. Peterschmidt wrote the music.

Copyright © 2023 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Annie Minoff is a producer for The Journal from Gimlet Media and the Wall Street Journal, and a former co-host and producer of Undiscovered. She also plays the banjo.

Elah Feder is the former senior producer for podcasts at Science Friday. She produced the Science Diction podcast, and co-hosted and produced the Undiscovered podcast.