Listening To Seashells, An Oracle Of Ocean Health

16:51 minutes

If you’re a beach person, few things are more relaxing than slowly wandering along the shore, looking for seashells. Your goal might be a perfect glossy black mussel shell, or a daintily-fluted scallop, or a more exotic shell full of twists and spirals, like a queen conch.

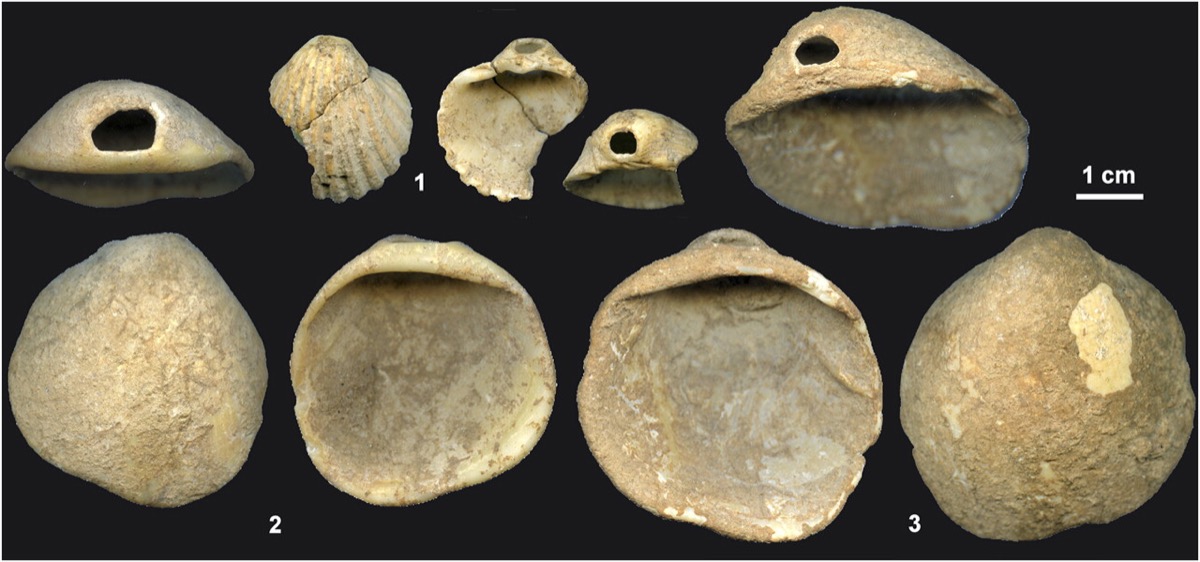

The human fascination with seashells dates back to prehistory. Shell trumpets have been found in Mayan temples. Shell beads abound in the remains of the midwestern metropolis of Cahokia. And the Calusa Kingdom, in what is now Florida, literally built their civilization on shells.

But seashells are more than just a beachgoer’s collector’s item. They’re homes to living creatures known as mollusks, built through a complex process called biomineralization. They’re also a harbinger of environmental change—and warming seas and acidifying oceans could change the outlook for shells around the world.

Environmental journalist Cynthia Barnett joins Ira to talk about the biology, history, and environmental significance of the seashell. She’s the author of the new book, The Sound of the Sea: Seashells and the Fate of the Ocean.

Read an excerpt of the book and check out more seashell photos below.

Cynthia Barnett is an environmental journalist in residence at the University of Florida, and author of The Sound of the Sea: Seashells and the Fate of the Oceans (WW Norton, 2021). She’s based in Gainesville, Florida.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

If you’re a beach person, few things are more relaxing than slowly wandering along the shore looking for seashells– that perfectly glossy, black mussel shell and maybe a scallop or some more exotic shell full of twists and spirals. But shells, of course, are more than just a collector’s item. They’re homes to living things and a harbinger of environmental change.

Cynthia Barnett is an environmental journalist. She teaches environmental journalism at the University of Florida in Gainesville. And her most recent book is The Sound of the Sea– Seashells and the Fate of the Ocean, just out from WW Norton. Welcome to Science Friday.

CYNTHIA BARNETT: Thank you, Ira. Thanks for having me on.

IRA FLATOW: Nice to have you. Let’s start on the biology side, if you will. Give us a definition of what is a sea shell and how does something make a shell?

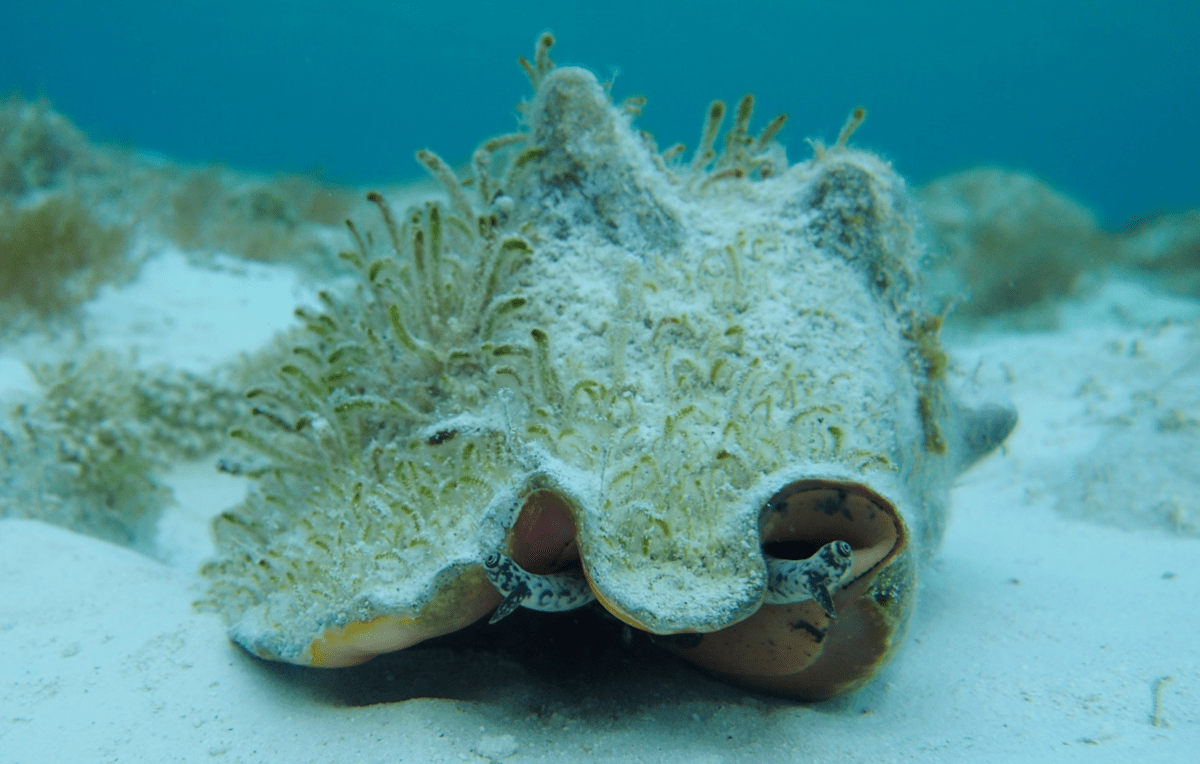

CYNTHIA BARNETT: A seashell is made by an animal, a wonderful animal called a mollusk. Mollusks, writ large, are the second largest group of animals in the sea and on land after the arthropods, that include insects on land and crabs in the ocean. So the animals in the sea that I’ve written about are the marine mollusks, which you sometimes might think of as sea snails. Or sometimes they’re called shellfish. And they build their shells with minerals from the surrounding sea water. So those that build a spiral shell, like a conch or a whelk, are known as the gastropods. And those that build paired shells like clams are the bivalves. And there are other mollusks as well, but those are the two primary ones that I focus on in this book.

IRA FLATOW: I just find that fascinating, and always have, that they must have a little chemical factory going on inside that assembles all of the minerals.

CYNTHIA BARNETT: They have a wonderful chemical factory to do what’s known as biomineralization. They have an apparatus called their mantle that is constantly taking in elements to create their wonderful shells.

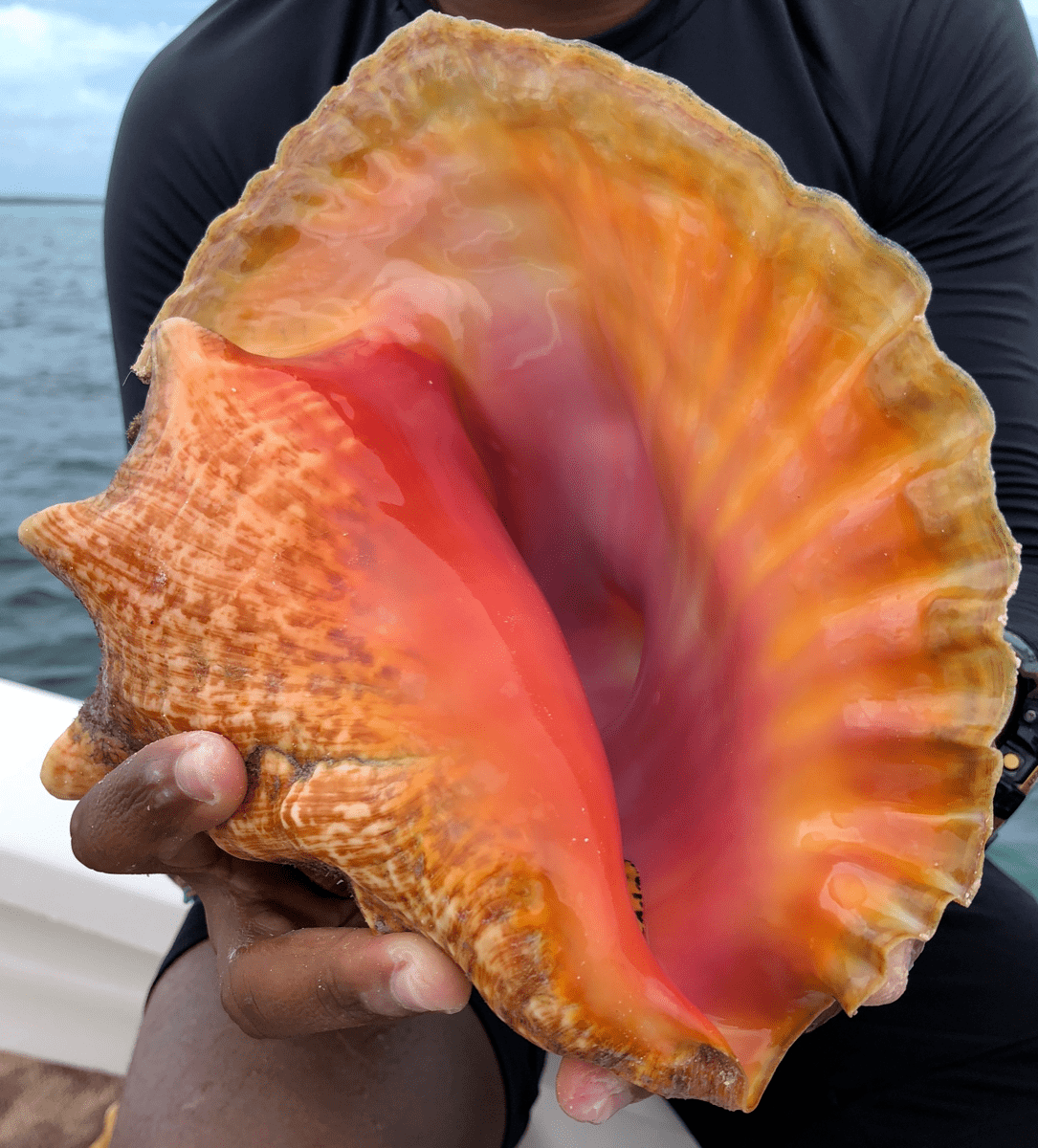

IRA FLATOW: So when we look at a giant conch for example, the top part of the conch is the first piece that was made?

CYNTHIA BARNETT: Yes. So if you hold a conch up with the spiny part at the top– it’s actually called the apex, the pointy top– that little pointy piece is the oldest piece of the sea shell. That’s where the conch fit when it was a tiny baby, or when it was still a larval creature floating around in the sea.

There are 50,000 different kinds of known marine mollusks. They build all different kinds of shells. And they do this all different ways and they’re born in many different ways. But I’ll give you the case of a queen conch. When it’s in its larval phase, its shell is just this beautiful, shimmering, gossamer bubble. And over time, that little gossamer bubble becomes the very top, the apex, of the shell. And ultimately, the animal buries itself. It lands in the sea grass, it settles in, and then it begins building the rest of the shell. And over time, that queen conch shell will become a monstrous five pounds of shell, sometimes.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Wow, that is fascinating. An idea that has always amazed me, and I’ve written about this a lot, is about how much of the world around us is made up of shells or their remains. In the sandy beaches we walk on, in the bottoms of the oceans, they’re just covered!

CYNTHIA BARNETT: I love that idea too, Ira. That idea that we walk on a world of shell. I already thought about that a lot as a reporter who specialized in water, that our limestone aquifers underfoot are the carbon that remains of life. So the world we walk on is the carbonate remains of all the calcified life that has ever lived. And that’s beautiful to think about. You’re right, they are beaches, they are mountains, and they also are marble. And I love this idea, too, that they built some of our iconic human spaces.

So if you think about the limestone Pentagon or the Lincoln Memorial or even the Empire State Building, these are really powerful buildings. And they owe their strength to incredibly fragile, soft beings.

IRA FLATOW: And you’re right that many people really don’t know what shells are.

CYNTHIA BARNETT: Yeah. So that is, really, the specific fact that got me thinking about this book and made me decide to write this book. I was actually giving a talk about one of my previous books at this lovely little seashell museum on Sanibel Island, here in Florida. It’s called the Bailey-Matthews National Shell Museum And I learned they had surveyed visitors, many of them tourists visiting Florida with their children, to find out B much people already knew about seashells. And some 90% of the respondents didn’t know that a seashell is made by a living animal. Most people thought they were some sort of rock or stone. And I just couldn’t stop thinking about that.

And I also started to think about it as a perfect metaphor for the ocean itself. Because we love seashells for their beautiful exterior while ignoring the animal that builds the shells or maybe just not knowing about that animal. And in the same way we’ve loved the oceans like a postcard, as this idyllic backdrop of life rather than the very source of life. So that’s the metaphor I was thinking about. The sea is so huge and so beautiful that it’s hard to understand, sometimes, what impact we’re having beneath the waves on things like water quality and ocean chemistry and certainly climate change. So I started thinking of seashells almost like an ambassador, to help explain some of the pressures that are happening in the ocean as a result of climate change and other human pressures.

IRA FLATOW: How much affect does climate change have on these creatures that make all these seashells?

CYNTHIA BARNETT: Well that’s a difficult question to answer. I’ll start with the broader answer about the impact of climate change on the oceans.

Essentially, climate change is changing the chemistry of the oceans. The carbon dioxide we send into the atmosphere has turned seawater about 30% more acidic than it was at the start of the Industrial Era. So this chemical change has begun to limit the carbonate that mollusks use to build their shells. And acidic waters are also boring into some shells, hitting or eroding them.

On the other side, mollusks are also threatened by the warming sea. Some parts of the ocean have already become too warm for some mollusks. But you can’t make a blanket statement about them. As I was mentioning, there are 50,000 known marine mollusks living in the oceans today. There are a lot more than that on land and in the sea. They’re experiencing and dealing with climate change in different ways.

So some of the tiniest seashells, known as pteropods or sea butterflies, were some of the earliest seen by scientists to really be impacted by what’s known as acidification. So some of these shells were seen to be dissolving in the Pacific Northwest. And that has been more than a decade ago, that scientists began to see that. And now that’s being seen all over the world. And now scientists have done all kinds of experiments to show what the oceans will be like, say 20 years from now or 100 years from now, and they show dissolution of shells in acidic water.

On the other hand, some mollusks are clearly beginning to adapt to the acidifying seas, some in only a generation or two. So there’s also a hopeful side of the story. And the other thing that I’ve enjoyed learning about them is just what incredible survivors they are. Like, they’re 500 million years old and those that are with us now have lived through incredible mass extinctions. And they’ve lived through acidic seas before, they’ve lived through warmer seas before, and so part of what’s really interesting about them is what they symbolize in terms of survival and adaptation.

But definitely some mollusks are really beginning to struggle to build their shells. And that includes some really important seafood that people rely on such as oysters and mussels.

IRA FLATOW: Will you talk about how long they have survived, another link to paleontology is paleontologist Mary Anning, maybe the origin of that famous tongue twister she sells seashells by the seashore?

CYNTHIA BARNETT: I was worried that you were going to make me say it. But you said it!

IRA FLATOW: In my business you have to know how to say that.

CYNTHIA BARNETT: She sells seashells by the seashore. I did it! So–

IRA FLATOW: Very good.

CYNTHIA BARNETT: –yes. Mary Anning, who’s a bit more well known now, was a British fossil expert who was in Charles Lylell time as a matter of fact. And she and her family had a curio shop on the Jurassic Coast of England and she found all kinds of extraordinary fossils– not only marine fossils but also dinosaurs. And she actually did some work for Charles Lyell, the famous geologist, and wasn’t credited for that work. And that’s another theme and another fascinating part for me, all the many different people who contribute to science and who are sometimes not recognized for centuries.

Another interesting woman in the book is Charles Lyle’s wife, Mary Elizabeth Lyell, who was a shell collector who had studied with her geologist father and also became an expert in the taxonomy of fossil shells. So I tried to give voice and credit to a lot of people who haven’t been credited in the past.

CYNTHIA BARNETT: Very interesting. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. In case you’re just joining us, I’m talking with environmental journalist Cynthia Barnett. Her most recent book is The Sound of the Sea– Seashells and the Fate of the Ocean. You write about another long ago seller of sea shore trinkets and how that became the foundation of Shell Oil. Tell me about that.

CYNTHIA BARNETT: Yeah, that’s another fascinating and surprisingly little known story. Shell Oil’s history actually dates to the early 19th century and a Jewish curio shop owner in the East End of London named Marcus Samuel. He imported tropical seashells from Japan.

There was a there was a shell craze– there had been an earlier shell madness in the 17th centuries in Europe, but it was mostly among really wealthy people and kings and royalty. By the Victorian age, this shell craze had spread to the middle class. So Marcus Samuel and his family sold seashells out of this little, tiny curio shop.

And he actually conceived the little seashell bejeweled boxes– when you are at a little gift shop near the beach, even to this day, you can find these little gift boxes that are covered with glued seashells all over them. He conceived those to sell in beach resort towns around Brighton and all around England. And those little seashell boxes were so popular in Victorian times, along with other sea shell curios, that it really made the family’s first fortune.

And Marcus Samuel grew and grew to be more of a trader with Japan. He was a very successful importer in his time. And then in the next generation, he had three sons. And they were still working out of their father’s seashell shop in the East End when they– it’s a long story, I devote a chapter to it, but they essentially beat John D Rockefeller in Standard Oil’s earliest bid for Global oil domination by– they built the first tanker that could travel through the Suez Canal with oil.

So they brought kerosene to Asia through the Suez Canal. And they named the tanker the Murex for the tropical seashells that their father had loved. They named it after this one seashell. And the middle son ended up founding the company Shell Oil, the same company we know today, as Royal Dutch Shell.

IRA FLATOW: Very interesting. And of course, the connection that you made before about global warming and climate change and fossil fuels, it comes full circle back to the beginning with Shell, a shell being the symbol.

CYNTHIA BARNETT: Yeah, the symbol. And it comes full circle in some incredibly specific and poignant ways. Since I finished the book, actually, some new research has come out about the Mediterranean. Just a few weeks ago, I interviewed a scientist named Paolo Albano at the University of Vienna who is working on warming in the Mediterranean. And they found the single most devastating die-off of mollusks along the Mediterranean coast, right around where the first Murex tanker entered the Suez Canal. It was one of the fastest warming places on Earth. And the great irony is that the one very common animal that they could find absolutely nowhere where they did this study was the murex. It shares the name of the first Shell Oil tanker.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Two degrees of separation.

CYNTHIA BARNETT: Yeah. Degrees is right.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. I guess that’s the unintended pun, right there. Well it’s a great book, Cynthia. I want to thank you for taking time to be with us today.

CYNTHIA BARNETT: Thanks so much for having me on.

IRA FLATOW: Cynthia Barnett is an environmental journalist, she teaches environmental journalism at the University of Florida in Gainesville. Her most recent book is The Sound of the Sea– Sea Shells and the Fate of the Ocean, just out from Norton. And you can read an excerpt from the book on our website at ScienceFriday.com/shells.

Copyright © 2021 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.