A Year Of Staying Home Has Led To A Global Chip Crisis

12:07 minutes

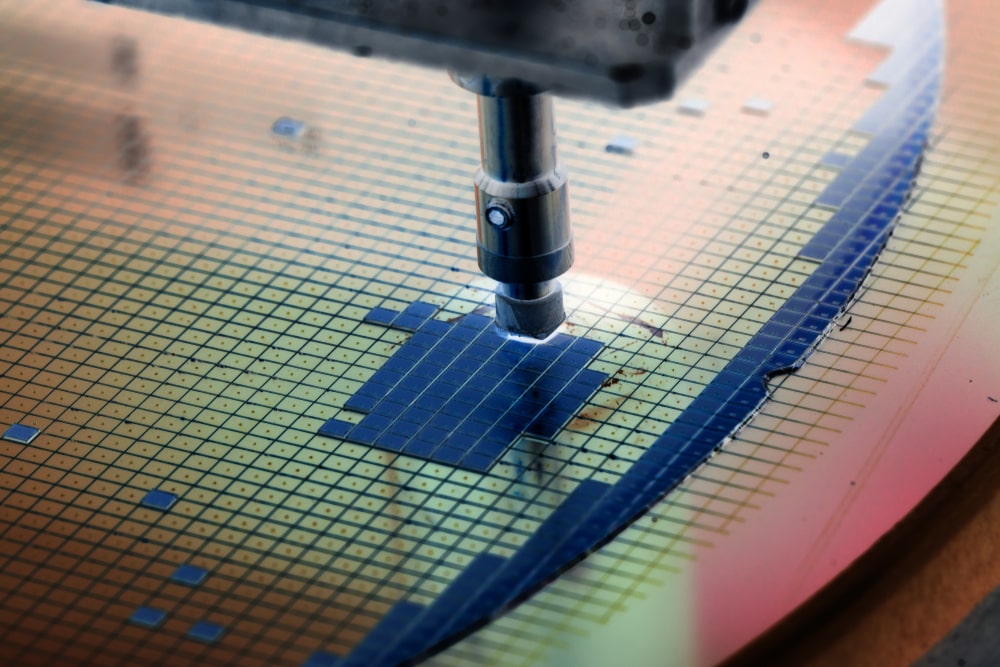

The global pandemic has led to a different kind of worldwide crisis: a global chip shortage. Demand for semiconductor chips—the brains behind “smart” devices like TV’s, refrigerators, cars, dishwashers and gaming systems—has spiked after a year of staying and working from home. And the pressure on global supply chains has never been greater. Sarah Zhang, staff writer at The Atlantic, joins Science Friday to explain what happened.

Plus, why AstraZeneca came under fire from U.S. regulators this week and how one scientist has finally solved a 20-years-long mystery about the bald eagle.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Sarah Zhang is a staff writer at The Atlantic, based in Washington, D.C..

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Car companies around the world are being forced to freeze production. They can’t get the computer chips they need for their brainy vehicles. The global pandemic has sparked a global chip shortage. Computer chips, they’re inside lots of things, phones, tablets, computers, refrigerators, dishwashers. And that’s part of the problem. Here to tell us more is Sarah Zhang, staff writer for The Atlantic. Hi, Sarah.

SARAH ZHANG: Hi. Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: So why have we run out of chips? What’s happened?

SARAH ZHANG: Oh, it’s kind of a perfect storm created by the pandemic. So remember, about a year ago, everything kind of froze in place, and factories were closed, and a lot of ships stopped running. So there was first a dip in production. And I think car makers, as you were talking about, they saw this and were thinking, oh, well, we don’t need to make as many cars. So they decided to put in fewer orders for chips.

But what actually happened is that we’ve all been stuck at home. And a lot of us maybe have needed to buy laptops or webcams to be Zoom all the time. And [INAUDIBLE] all the appliances, whether it’s like fridges, or TVs. And all of these things require semiconductor chips. So what you now have is also a huge demand for all these electronics that require chips. So the car companies were kind of locked out. They’ve suddenly found themselves, oops, we don’t have any cars. So now they’re there idling their factories, while you have all the electronics companies still going full bore, making all these things that we ordering. And you have phones and game consoles, they’re also getting delayed because we’re all kind of caught up in this chip crunch.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Is there any estimated time for things getting back to normal?

SARAH ZHANG: Yeah, it’s great question. It kind of depends a little bit about what we do, right? So first of all, it depends on do we keep ordering a lot of electronics? It’s possible that the demand might slow down a little bit. But with car companies I think we will be looking into disruption until later this year.

IRA FLATOW: Speaking of a disruption, let’s talk about this global shipping problem. How is that boat in the Suez Canal doing? It had something to do with the weather, did it not?

SARAH ZHANG: Yeah, it’s still stuck. So what happened was earlier this week, a giant container ship, which is as big as the Empire State Building, turned on its side, got stuck in the Suez Canal in Egypt. And what happened is it seems to be like the weather is kind of bad. There’s a sandstorm. So it was a little bit hard to see. And the winds were really strong.

And you can imagine these container ships. They have containers stacked up really high. So they’re kind of acting like a giant sail. And if you have this wind and maybe if you maneuver incorrectly, the ship got stuck. It’s stuck sideways. And it seems like the sides of the canal are actually quite shallow. So it seems like quite a bit of it is kind like in the sand right now.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. As a sailor, I can relate to this running aground in all that sand. And the Suez Canal is a major shipping lane, isn’t it?

SARAH ZHANG: Yeah. All of the traffic between Europe and Asia is going through the Suez Canal. You can imagine without the canal, ships would actually have to sail all the way down to Africa and back up. So this would be cutting their journeys a lot shorter. But the delay, which has been going on for almost a week now– and it’s possible it might go on for weeks more. This is what officials are saying now. I think because of that, some ships are actually saying, well, rather than waiting this out, maybe we do just sail down South Africa and back up again.

IRA FLATOW: These ships are such high-tech objects. They’re the biggest things in the world. And you have to use the most basic way to get them out, just dig them out or something, right?

SARAH ZHANG: Yeah, so there are pictures you might have seen. There is a tiny little excavator that is digging out the sand that the ship is stuck in on one end. They also have tugboats that are kind of trying to straighten the ship out and pull it out of the sand. The problem is that the allyship is so big and so heavy that if you kind of pull really hard on one end, you might end up damaging the ship rather than dislodging it from the sand. It could come to needing to take some containers off of the ship to lighten it. And that will take a lot of time just because you need a lot of specialized equipment to kind of pull those containers off of the ship.

IRA FLATOW: Moving on, there’s some drama, is there not, with AstraZeneca and its vaccine data? Can you help us tease out what happened there?

SARAH ZHANG: Oh, yeah. So I think at the end of the day, what happened is AstraZeneca has done a terrible job talking about the results, even though their vaccine actually looks very good. So what happened is in the fall, AstraZeneca released results from its trials in the UK and South America. And the results were kind of muddled. They kind of had a dosing error in one arm. And there are a lot of different arms. It’s just kind of really hard to say exactly what the efficacy number for this vaccine is.

So the US basically said, we’re not going to mess with that. We have our own trial of AstraZeneca vaccine in the US that is very well designed. And we’re just going to wait for that data. So that’s what we got earlier this week. And it looked really good. It looked like the vaccine was 79% effective.

And then a little bit more drama, but a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases released a statement a day later saying that independent data safety monitoring board has some concerns about the data, that it was slightly outdated. What happened is that AstraZeneca had decided to analyze the data after a certain number of COVID cases in its trials in both the placebo and the vaccine arm. And that happened somewhere around the middle of February. But since then, obviously, we’ve had a little bit more data, which this independent board had seen. Came out later that with this new data efficacy a bit closer to 74%, so really not a huge difference, a lot of back and forth over very little. And I think that maybe does obfuscate a little bit the underlying fact, which is that this vaccine does look quite effective.

IRA FLATOW: So as we enter the late stages of this pandemic, we’re starting to talk more about recovery from COVID. And there some people who are working on relearning to smell after COVID. Tell us about that.

SARAH ZHANG: Yeah, it’s called smell training. It’s a little bit like physical therapy for your nose. So I talked to one woman who is going through a small training. Basically what you do is every day you take four bottles of essential oils. The typical scents are rose, clove, eucalyptus, and lemon. And you just sniff them for 20 seconds.

And it is– you’re kind of just training your notes, right? Sometimes people say you should be thinking of memories while you’re smelling these smells. So while you’re smelling lemon, think of, for example, eating lemon pie. And it’s really just kind of attuning your brain a little bit more to the smell. So we’re not really sure exactly what happens.

But what’s maybe happening with COVID is that the virus is not necessarily infecting the smell neurons in your nose but kind of damaging the support cells around it. So these neurons end up not be able to regenerate over time. And this small training may just help that regeneration and make sure the rewiring goes back correctly.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, because smell is so much tied to memory and emotions. You smell something. It’s very evocative of some period in your life.

SARAH ZHANG: Yeah, absolutely. And one of the really strange things of relearning how to smell a lot of times people go through this period of smelling phantom smells or distorted smells, where like their coffee can smell like sewage. They smell burning all the time. And we don’t really know why these smells are usually really, really bad and obviously really distressing if you’re eating food and it like sewage.

But it could be that your brain is just getting those scrambled signals. And because anything that you’ve never encountered before, it might be dangerous. It’s interpreting the scrambled signals as danger.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s move on to a new theory about two unusual spots in the Earth’s core. I love Earth science. Tell us about what’s going on here.

SARAH ZHANG: Yeah. So there are two huge blobs inside the Earth. So this–

IRA FLATOW: Is that a technical term, “blob?”

SARAH ZHANG: Well, let me tell you the technical term. You’ll know why I’m saying blobs instead. The technical term is large low-sheer velocity provinces.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s stick with blobs, yeah.

SARAH ZHANG: So these blobs, they’re huge, basically the size of continents. And they’re inside the Earth’s mantle, which is a layer that’s right under the crust. And they’re at opposite ends of the Earth. So one is right under the surface of West Africa. And the other is under the Pacific Ocean.

And we know they exist because when seismic waves pass through them they seem to slow down. And it could be because they’re hotter than the rest of the mantle. Or it could be that they’re a little denser than the rest of the mantle. And there’s a new theory that says that these blobs, these dense blobs, may actually be the fragments of this ancient protoplanet that hit Earth. And that collision created the moon.

IRA FLATOW: Whoa. Whoa. That’s one heck of an idea.

SARAH ZHANG: Right. It’s like our mantle like a graveyard for ancient planets. So what happened is we don’t really know exactly how the moon formed. But the prevailing hypothesis is that this big planet collided with the Earth, which as you can imagine, was pretty catastrophic, created this huge debris cloud. That coalesced into the moon.

But then what happened to the rest of the planet? Could be that it’s still stuck inside the Earth. And that’s what these blobs are.

IRA FLATOW: So what happened that people suddenly started talking about these blobs?

SARAH ZHANG: Yeah, this idea has been out there for a while. But there’s a few different lines of evidence. So first of all, magma kind of flows around the blobs. And they kind of feed volcanoes that erupt in Iceland and Samoa. And if you look at the lava on those islands, they seem to have records of radioactive elements that would have only been there when Earth was very, very young, about when the moon had formed. So these blobs seem somehow really old.

Another is just you do some modeling and do some math on what the moon is made of. It seems to be just a little bit denser than the Earth. And it seems to be that when that planet merged with the Earth, it would just have kind of created these slightly denser blobs that is now what we see in our seismic energy.

IRA FLATOW: Oh, I love this kind of stuff. Let’s move on to a decade-old mystery about the bald eagle. It’s been solved. Is that right?

SARAH ZHANG: Yes, it took 25 years. But what happened is that they suddenly started dying at a lake in Arkansas called DeGray Lake. These eagles, they seemed like they were going blind. They were flying straight into cliffs or flying into trees. And even when they were on the ground, they were kind of walking around, one scientist told me, like they were kind of drunk.

And it turns out they had these little lesions in their brain. But for a long time nobody knew why. It didn’t seem to be bacteria. It didn’t seem to be any known pathogen, any heavy metals or pollutants. It wasn’t any known toxin.

And so 25 years, and now they finally have the answer, and it’s really complicated. So it explains why it took them so long. But the answer is that the bald eagles were eating waterbirds that we’re eating an invasive plant that lived in these lakes. The plant itself is not poisonous, but it had cyanobacteria that lived on them.

And these cyanobacteria only make this toxin in the presence of an element called bromine. So you had all of these things kind of like having to, like, a perfect storm. But they created this toxin that ended up killing all these bald eagles all the way back 25 years ago.

IRA FLATOW: And so the bromine came from the cyanobacteria? Or it was just present with the cyanobacteria?

SARAH ZHANG: It’s present in the water. And it’s actually kind of a mystery exactly where it came from. So it seems like the plant that the cyanobacteria are living on seem to sequester the bromine. But where’s it coming from the first place? One hypothesis is that it actually might be in the herbicides that were used to try to get rid of the invasive water plant, ironically.

Or maybe it was part of the waste water from power plants because bromine is used to remove mercury from coal. But we don’t know exactly where the origin is. But it’s definitely in there. And that’s the condition in which these toxins appear.

SARAH ZHANG: Sarah, terrific reporting. Thank you for taking time to be with us today.

SARAH ZHANG: Yeah, it’s thanks great to be here.

IRA FLATOW: Sarah Zhang, staff writer for The Atlantic.

Copyright © 2021 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.