Skyscraper Bridges, Floating Airports, And A Dome Over Midtown

17:25 minutes

The New York City skyline is one of the most iconic in the world. But for all the structures New York City is known for, there are dozens of intriguing ones that were never built. How different would the city look had architect Buckminster Fuller followed through on a plan to build a dome over midtown Manhattan? What would have become of the East Village had city planner Robert Moses built the Lower Manhattan Expressway? Could a radical plan for the Metropolitan Opera House have changed the course of modern architecture if bureaucracy and red tape had not gotten in its way?

[Can you spot the engineering tricks hidden in buildings?]

We now have a way to answer some of these questions. Never Built New York is a collection of architectural drawings and artist renderings of structures and other ideas that didn’t come to fruition. It’s a unique look at New York through various historical eras, such as the Gilded Age and the mid-20th century. And yet the concepts covered in Never Built New York don’t seem entirely unfamiliar. Indeed, they reveal a concern for the environment and a preoccupation with space that are still on the minds of New York City residents today.

Co-author Sam Lubell joins us to discuss the architecture of New York that never came to be.

[Venomous or poisonous, can you spot the difference?]

Author and journalist Sam Lubell is the co-author of Never Built New York (Metropolis Books, 2016). He’s based in New York, New York.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. The New York City skyline is one of the most iconic in the world. The Empire State Building, the World Trade Center, the Brooklyn Bridge, and of course my favorite, the Chrysler Building. But for all the structures New York City is known for, there are dozens that were never made, skyscrapers built along the George Washington Bridge, a floating airport on the Hudson River, a dome covering midtown Manhattan.

Sounds crazy right? But they were real ideas once. Now all that’s left of these whimsical plans are artist’s drawings and renderings, which have been carefully collected into a new book by my next guest. And to look at them makes you wonder if just maybe in some alternative universe, those things really do exist. Sam Lubell is a contributing writer for Wired and co-author of the new book, Never Built, New York. And we won’t be taking your calls today, but you can comment on Twitter at scifri or at sciencefriday.com.

Welcome back, Sam.

SAM LUBELL: Thanks, Ira. Great to be here.

IRA FLATOW: Now, your new book is like an encyclopedia of New York projects that were never completed. How did you find about these things if they were never built. How did you start your journey on that?

SAM LUBELL: Well, that is the challenge. You can’t go to the library and look for things that never happened because they don’t get documented very often. But what you do is you really get to know the history of people that build in the city. So you look for all the firms that are building now, and you ask them what didn’t happen.

And a lot of what you do is you go to archives that collect the work of all the architects throughout the history and the engineers and the builders throughout the history of the city, well over 25, 30 even more of those archives. And those are not just in New York, but they’re all around the country. And they’ve got incredible stuff that’s just sitting in vaults, sitting in cold storage.

IRA FLATOW: Do they ever think that maybe they can resurrect those ideas and someone will pull them out 20, 30, 40 years later?

SAM LUBELL: I don’t know if the archivists think that, but there’s always that thought that some of these things might come back, and like everything else, ideas do come around. And you wonder, some of these ideas actually could. So it’s a good question.

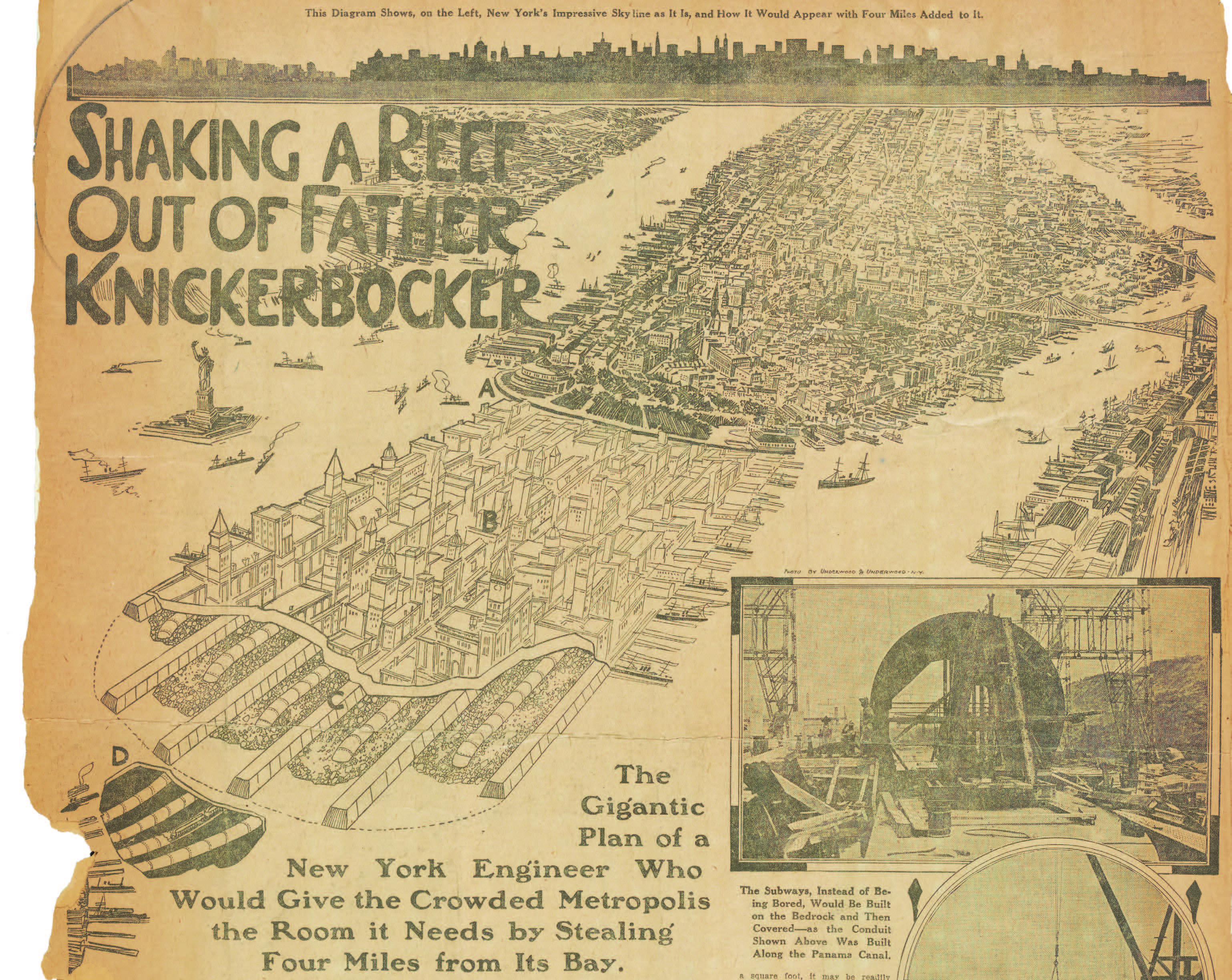

IRA FLATOW: Let’s go to some of the ideas, some of the projects, and some of them would have dramatically altered the landscape of New York. For example, there was one plan from 1911 to extend the bottom of Manhattan into the bay almost to Staten Island.

SAM LUBELL: Pretty close.

IRA FLATOW: What was the idea there?

SAM LUBELL: Well that was by a really well respected civil engineer named T. Kennard Thompson, who had worked on several of the most important projects in the city at the time. He was not a crackpot by any means. And for over 20, almost close to 30 years, he proposed this idea called the City of New Manhattan. And the idea was basically to build another Manhattan off the tip of Manhattan as you said, extending all the way down to basically to Staten Island, swallowing Governor’s Island, swallowing basically all of New York Bay and built all on landfill.

And it wasn’t a pie in the sky idea. He was, in collaboration with other engineers, talking to people in the city. He had the backing of a lot of business groups in lower Manhattan who were scared that the momentum of business was moving northward toward midtown, which it was. And they were no longer going to be the center of things, but if things went south, they’d remain the center.

And he tried. It was on the cover of The New York Times. It was on the cover of most major newspapers at some point over that 20 years, several times if not if not once on each of those. So this was not a joke of an idea. And it was a time when ideas like this weren’t considered that far fetched amazingly.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah and I noticed there are ideas in the book for making sort of a beach out of the West Side of New York, which I have said all the time. You know, if you’ve got coastlines like you have in Chicago with big cities, why not have a beach or something? What happened to those ideas?

SAM LUBELL: Well, yeah I mean, people have thought of– Manhattan is a very limited space. And it’s one of the most aggressively built areas in the world. So there’s always ideas for how do you make it more livable? How do you make more space in it?

There was an idea by a developer who we like to think of, never built all-star named William Zeckendorf and his sons are still practicing, still developing, for an airport along the entire west side of Manhattan, covering more than 40 blocks and you’d have airport above a giant concrete landing strip. You’d have boats coming in from the side. You’d have office buildings along the other side, kind of using every square inch.

And you have other people that thought of floating kind of infrastructure that was going to create new performing arts spaces. And some of these ideas. Now you have this plus pool, which is going to be building a pool, you know, floating in the river in Manhattan. So these kinds of ideas, these kind of maybe crazy ideas, they keep coming back. And these ideas are not always as foolish as we think they are in retrospect.

IRA FLATOW: There was a very interesting– Bucky Fuller, Buckminster Fuller, wanted to put– and you have it in the book –a giant dome over the middle of Manhattan.

SAM LUBELL: Yeah, I mean, a lot of the ideas we have were very close to happening. That’s not one that was particularly close, although it was very well researched. And Bucky Fuller wanted to build domes pretty much everywhere. And he had been talking to developer about doing one further upstate, a serious plan to do that. And then he consequently came up with this plan to basically shelter New York from all the elements.

And it was a time when people really believed in the power of technology. And they thought well we can do kind of anything. We’re building domes. We’re building spaceships that go to the moon. Why can’t we build a dome over Manhattan to get rid of all this pollution, get rid of all the problems of weather, because as we know New York doesn’t have the best weather. It really was a time when these things were thought that they were possible. It’s both scary and exciting that people were thinking this way.

IRA FLATOW: They also scrapped plans to fill in the East River. There were plans to fill in the Hudson River, plans to fill in the East River.

SAM LUBELL: Yeah, like I said, Kennard Thompson was the most fully fleshed out. Some of those other plans, you have like in different science periodicals, people were coming up with these ideas all the time.

IRA FLATOW: I think Modern Mechanics is for filling in the Hudson in 11934.

SAM LUBELL: Yeah, but some of those again, some of these were engineers. One engineer was working with the city was coming up with this. And you know the idea was, we have two rivers. Why not fill one of them in and you get more space? I mean, we have so many problems of space in the city. And you have these two rivers around here.

You’ve got a backup plan with the Hudson. And why not fill in the East and you’ve got like twice the space. You’ve got twice the tax revenue. Let’s do this. And people had already built the Panama Canal. They were filling in most of Boston with landfill. This wasn’t considered that far fetched.

And I think you subsequently had overreach to an extent where things kind of got out of hand in the mid-century that people now, I think are so hesitant to do this kind of grand thinking, both for better and for worse, I think we have environmental responsibilities and knowledge that we didn’t have then. But also we’re scared to think big and I think people are a little tired of that. So there’s pros and cons to these ideas.

IRA FLATOW: One of the great parts about your book, Never Built New York are the great color photos you have, I mean, the actual renderings, the drawings, the newspaper clippings, everything. How did you find all of these? That’s really what makes the book work, big, beautiful color photos and drawings.

SAM LUBELL: Yeah, well I think one of the things that people really respond to about this book, and we also did a book in Los Angeles, Never Built Los Angeles as well as an exhibition, is these drawings. Because to a large extent, this art of architectural drawing is sort of dying, if not close to dead. And for a long time, this is the way people rendered things and they did it in such an artful, extremely beautiful way.

And you go to these archives that I was mentioning. You go to the Avery Archive at Columbia. You go to archives at Yale, Princeton, Columbia. You go to the New York Historical Society, pull these things out. They’re the size of a table. And they’re absolutely stunning. They take your breath away.

And it’s a way of seeing the world that we are now losing to this hyper real vision that computers are creating, which is a very limited palette created by programs. It’s not out of people’s imaginations. There’s not this sort of immediate response that we have. We are sort of kind of jaded by the way we see things.

But it’s just so absolutely beautiful. And you find these in archives and then archivists who know the material so well, will find more, and things that oh by the way, there’s this amazing you know, drawing of City Hall. They’re going to knock down City Hall and build this. We did we found that at the Archives at the University of Pennsylvania.

We didn’t know that there was a plan. He just kind of pulled it out of nowhere. And that’s how you find a lot of this stuff.

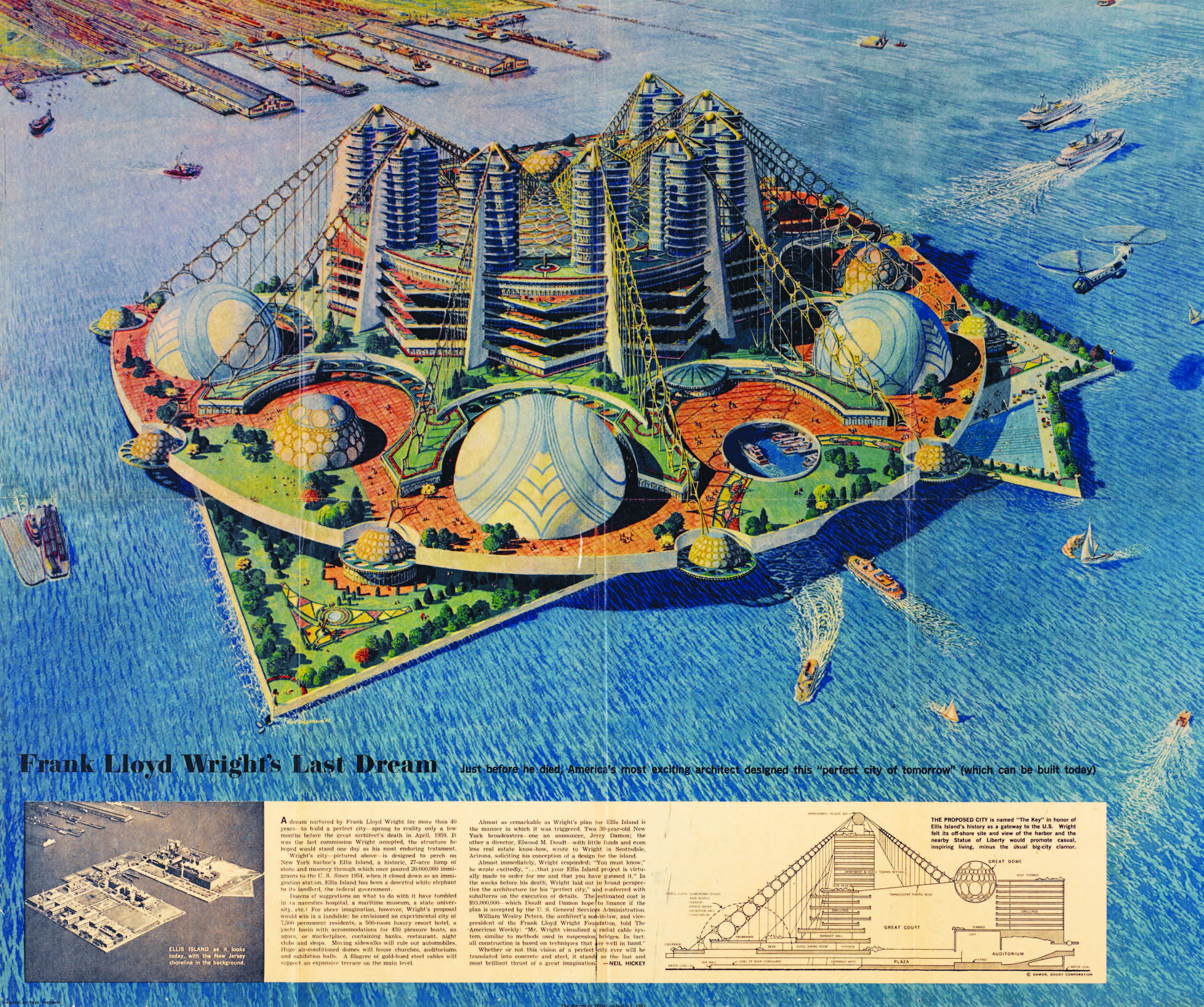

IRA FLATOW: One of the more interesting– I mean, there’s so much going on in this book. And one of the most innovative designs I think is a Frank Lloyd Wright design for recreating Ellis Island. Wow. You have to see it to believe it. You reminded me of that about the drawings. This is not the Ellis Island we have today.

SAM LUBELL: That’s definitely true. And it’s again, the book shows these sites that you think are sort of sacrosanct. You know like, oh yeah, it’s Ellis Island. And it’s like well actually, because Ellis Island you know only served its purpose until the 1950s. And then the national government put it out to bid for developers. And there was a plan for a prison at one time. There was a proposal for this great resort that didn’t happen.

And the highest bid actually came from this group that hired Frank Lloyd Wright to come up with what was called The Key Plan. And it was basically a city within a city.

IRA FLATOW: I love how they describe it here. You say, casual, inspired living minus the usual big city clammer.

SAM LUBELL: Yes, exactly.

IRA FLATOW: It’s Ellis Island.

SAM LUBELL: It’s an escape. It’s not the place to come into America. It’s the place to escape for from New York. I guess. And Frank Lloyd Wright sort of espoused that. He was famous for Broadacre City, which sort of was living away from the city. And you’ve got his organic architecture all around. You’ve got greenery around you. You’ve got these double bubble domes around you that are schools and theaters and he designs every square inch of it, from the boats to the toilet flushers.

Everything is very Frank Lloyd Wright vision, amazing. I mean the drawing again, I saw that at the Avery Archive at Columbia. And it’s almost like you want to pass out when you see how beautiful it is.

IRA FLATOW: It’s amazing. It is, it’s amazing. One of the key architects of New York was Robert Moses. His highways, the Triborough Bridge is his, highways all around New York City. He couldn’t do, he couldn’t finish. He was called the King of New York at one point. That’s how powerful he was. But he wanted to bring a superhighway right down the middle of New York, didn’t he?

SAM LUBELL: He wanted to bring several highways down the middle of New York. And he was an example of just how powerful bureaucrats had become. And he was the most powerful of them all, as you know. And I think people kind of think he built everything he wanted. But never built show– and the tides of history, and the tide of history started to turn against him and that’s when you get these never built Moses projects.

And I think a lot of people know about the Lower Manhattan Expressway that Jane Jacobs famously helped lead the charge against. And that would have basically wiped out Soho and most of the Lower East, which is terrifying. But not at all, it was part of popular conscience that things like that were happening and it was sort of a normal thing.

But he also wanted to build a highway down actually, about a block from here, on 32nd Street through mid-Manhattan, a raised highway going through buildings, called the Mid-Manhattan Expressway. And that came very close to being completed. I don’t think people realize that that was another one. It’s astonishing.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from PRI, Public Radio International. Talking with Sam Lubell, co-author of Never Built New York, co-authored with Greg Goldin. And the graphics in this, if you’ve ever wondered whatever, you know, hey, why don’t they build that? It seems like somebody had at one point thought of some idea. was? There a period where most activity was going on? Can you narrow it down?

SAM LUBELL: That’s a really good question. Because we obviously can’t find everything. But from what we found, the most fertile periods for what we found were sort of I think, at the turn of the century and the beginning of the 20th century, when the city was really forming its modern self. You start with the Beausart plans that didn’t happen.

And then you move into stuff, the famous, you know art deco buildings. You see the ones that were built, the Chrysler Building, the Empire State. But there are so many that weren’t. And I think the time when we really saw the most of those was during the Great Depression. It’s like the great collector of never built projects.

There was a tower near Madison Square Park that was going to be 100 stories and got knocked down to about 29 because of the Great Depression, although you can see it still has the width for that tall of a building. And those projects go on and on. And then, I think the next time when there was another iteration of the city, which was mid-century, which we were just talking about. Which is when I think the city was in a lot of ways trying to rethink itself and sort of save itself from its decline.

And you had people like Robert Moses trying to build these gigantic schemes that would have, they think saved the city. I don’t think they would have.

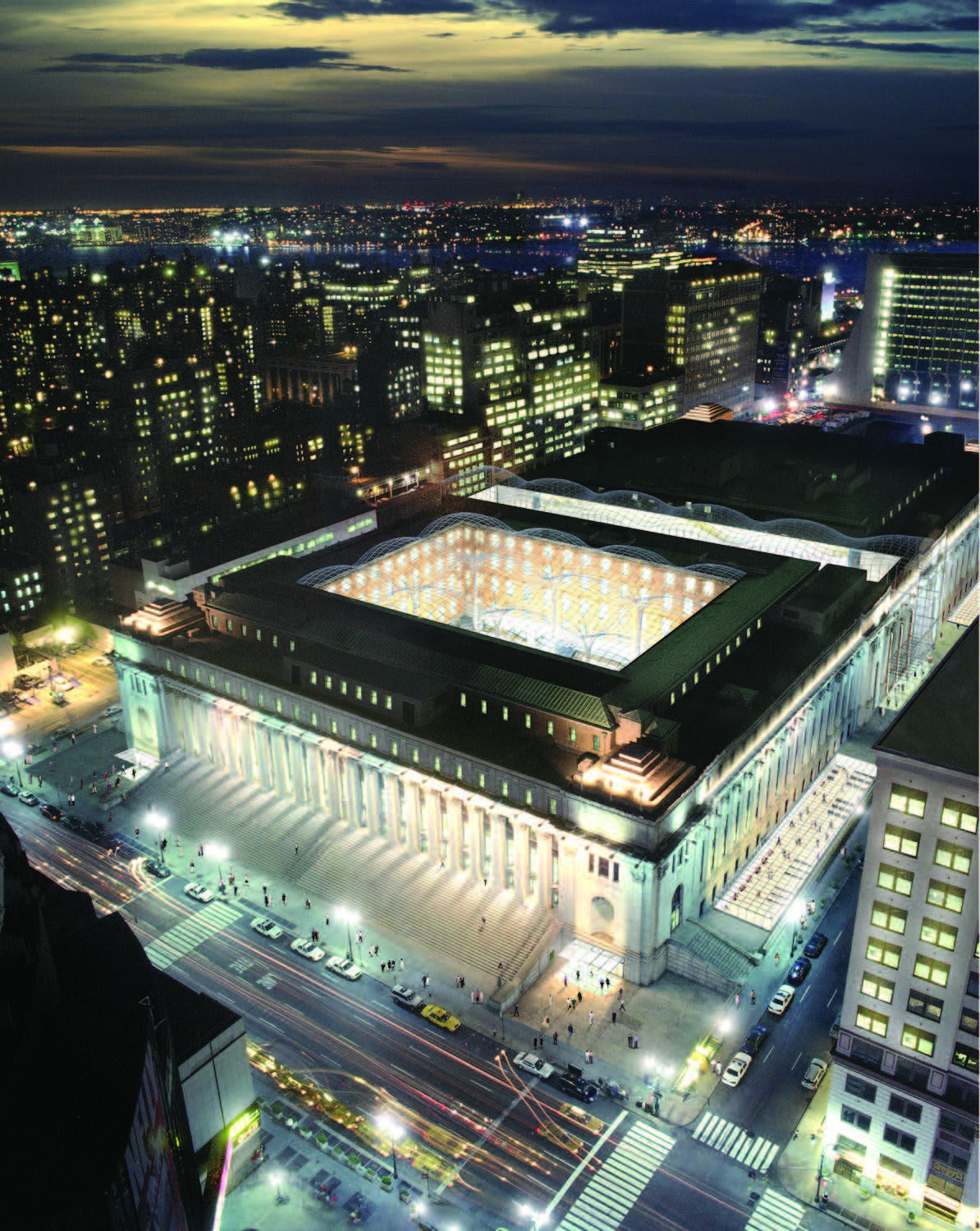

IRA FLATOW: And then you have some things that have never still been built, right, or used to be built? And I’m thinking especially about Penn Station. Penn Station used to be this gorgeous thing that they took apart, what in the 60s? They took it down, and they still have not figured out how to put it back.

SAM LUBELL: No. And we’ve got more than half a dozen attempts to build a new Penn Station, that may have recreated or at least captured some of the magic of the original, although you never really can. It was astounding. And on the other side of the coin, we have more than half a dozen attempts to knock down Grand Central Station. Again, these things that you think are sacred in the city really weren’t. And that one came within a whisker.

IRA FLATOW: Wasn’t Jackie Kennedy–

SAM LUBELL: She was a big part.

IRA FLATOW: Big part of saving it.

SAM LUBELL: There was a one of several plans, a plan to build a skyscraper by Marcel Breuer, who designed the Whitney, among many other things, was going to basically be chomped right on top of Grand Central Station, and basically destroying it. And that was killed by a preservationist led by Jackie Kennedy. And the fight for that went all the way to the Supreme Court, and really kind of gave the kind of a fledging preservation movement its teeth for once.

IRA FLATOW: Are there projects going on all the time we don’t know about?

SAM LUBELL: Oh yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Somebody wants to do this and that and they’re just sitting on a table. Do you know of any that are really creative, that you’d like to see?

SAM LUBELL: That I’d like to see?

IRA FLATOW: Yeah.

SAM LUBELL: Now?

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, I mean, is there something on somebody’s drafting table now that you came across and said, oh, that would be a great idea.

SAM LUBELL: Well, you’re always coming across really good ideas. You know I think, there haven’t been as many grand ideas, I think to change the city lately as there– I think the one exception is the Highline. And now there’s a plan called the Lowline, which I don’t think is the same scope of that. But it’s interesting. They were trying to rethink subterranean space.

IRA FLATOW: That’s to go under the West Side.

SAM LUBELL: It’s to go under the Lower East Side.

IRA FLATOW: Lower East Side.

SAM LUBELL: And it’s really much more moderate in scale. And I think that the name is a little bit of branding. But it’s an interesting concept, which is how do you bring natural light? How do you bring new life into subterranean areas of Manhattan? It’s like again, rethinking how you live in Manhattan, and how you use this limited space.

I like that plus pool. And we will see if that will be built. We don’t know. But I like the idea of how do you live in the river? And the river, how do you make it a place that’s not a place you’re scared of and a place that you want to embrace. I love the idea of using the city in new ways. And people are always thinking of new ways to do that.

IRA FLATOW: And a lot of new ways that never got built are in Sam Lubell’s book, a contributing writer for Wired and co-author of this book, great book, great holiday book, Sam. Never Built New York. Sam Lubell, thanks for taking time to be with us today.

SAM LUBELL: Thanks, Ira, great to be here.

IRA FLATOW: One last thing before we go, there’s still time to join us for Science Club. And this time we’ve invited our listeners, invited you to break it down, rotary phones, baseballs, complex molecules. You name it, break something down. We’re giving you permission to bust stuff up.

So if you need something to do this holiday weekend, it’s not too late to join the fun. Break something down and tweet it or share it on Instagram with the hashtag I broke it down, or visit sciencefriday.com/scienceclub to submit your project for a chance to be included in our on air wrap it up on December 9th. That’s all the time we have.

Charles Bergquist is our director, senior producer, Christopher Intagliata. Our producers are Alexa Lim, Annie Minoff, Christie Taylor, Katie Hiler. Luke Groskin is our video producer, Rich Kim, our technical director, Sarah Fishman and Jack Horowitz are our engineers. And the controls here at the studios of our production partners, the City University of New York. Have a great holiday weekend. We’ll see you next week. I’m Ira Flatow in New York.

Copyright © 2016 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of ScienceFriday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.