A Teen Inventor Builds A Fingerprint Scanner for Gender Equity

10:28 minutes

The World Bank estimates that around one billion people worldwide don’t have official proof of identity. Without legal identity verification, opening bank accounts, voting, and even buying a cell phone is challenging or even impossible. This issue disproportionately affects women—around half the women in low-income countries do not have proof of identity, which limits their independence and the resources they are able to access.

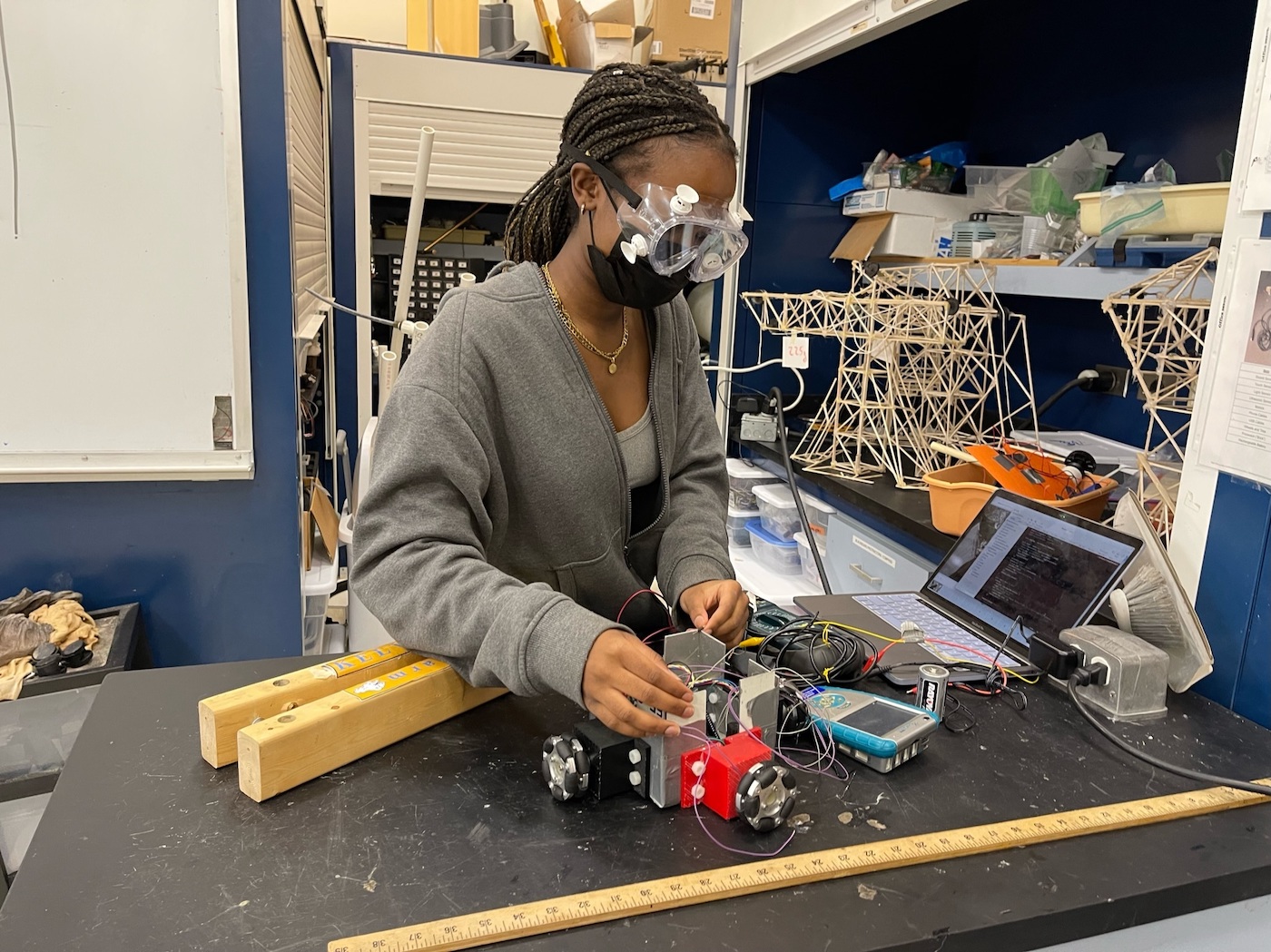

Looking for a solution, 16-year-old Elizabeth Nyamwange invented Etana—an affordable fingerprint scanner that could provide women with a form of digital identity. Her project to close the gender identification gap earned her first place in HP’s Girls Save the World challenge.

Ira speaks with Nyamwange, based in Byron, Illinois, about her innovation.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Elizabeth Nyamwange is an inventor based in Byron, Illinois.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Over the next few weeks, we’re going to be bringing you stories from game-changing young innovators who are taking on big problems. To kick us off, a teenage inventor combining blockchain technology and social justice.

Here’s the background. The World Bank estimates that 1 billion people in the world don’t have an official proof of identity. That means that opening bank accounts, voting, and even buying a cell phone is challenging and sometimes even impossible. And this is very much a gendered issue. Around half the women in low-income countries don’t have IDs.

My next guest saw that challenge as an opportunity. Looking for a solution, 16-year-old Elizabeth Nyamwange invented a device called Etana. She recently won first place in HP’s Girls Save the World challenge, in which more than 800 teams submitted their ideas on how to better the world. Elizabeth joins me now from Byron, Illinois, to tell us more. Welcome to Science Friday.

ELIZABETH NYAMWANGE: Hi, thank you for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Elizabeth, I didn’t realize how huge the global identification issue is. 1 billion people is bewildering. How did you learn about it?

ELIZABETH NYAMWANGE: So I really started becoming interested in the gap between women and men in digital identification post-COVID-19, I think, seeing a lot of the effects or the gender gap being exacerbated by the pandemic. And women were staying at home. And the form of gender and inclusivity took a very different approach in other countries, let’s say, as opposed to the United States. So that’s how I started looking at it in specific.

I’m from Kenya, so I have a lot of family back home. And we’d always talk about how a lot of girls were forced out of school, put into work early, things like that– didn’t have bank accounts. And those numbers COVID-19 just made so much bigger. So whenever I was doing research on gender post the pandemic, this is the kind of stuff that I would find. And identity was just something that really, really interested me because I saw how it impacted so many different sectors and shaped these women’s lives.

IRA FLATOW: So the root of inequality, the root of the problem, is not financial. You need an ID before even considering, let’s say, banking.

ELIZABETH NYAMWANGE: Yes. You need an ID for basically everything, and I think it’s something that we in the States take for granted. But to even receive judicial protection, to receive health care a lot of the times, open bank accounts, even work in the formal economy, you need some form of identification.

IRA FLATOW: So women have very limited freedom to do what they’d like without having these IDs.

ELIZABETH NYAMWANGE: Yes, exactly. The reason it’s such a big problem in these areas is because the concept of gender and the cultural restraints that it holds mean that a lot of people don’t necessarily think women should have or want them to have these IDs because, obviously, it opens up a different sector and a different world for them to start to experience. And a lot of people– maybe governments, family members– think that they don’t need it, so they don’t prioritize it. And that’s what also makes this such a big crisis because if people in their areas aren’t prioritizing it, then no one else is really going to notice that there’s even a problem to begin with.

IRA FLATOW: What made you take on this idea? What was the catalyst that finally said to you, I have to work on this problem?

ELIZABETH NYAMWANGE: I had initially actually started with finance, looking at how to give these women different types of banking. And I had seen or attended a lot of hackathons that we’re working with in the financial sector, working to provide bank accounts for women in remote areas or for refugees in crisis– basically humanitarian situations. And from that, I started researching, then, what are the constraints that women already don’t have that are stopping them from getting these bank accounts?

And from that is where I started looking into identification itself, which at the basis of all of this, again, was my family. I do talk to them a lot– quite constantly, actually– and, oftentimes, I hear a lot of stories. They tell me a lot of things that they like, a lot of things that they don’t like. And maybe while it’s not in the intention for me to try and change something, when I hear things repeatedly, and I know it’s something that I may be taking for granted perhaps, I want to see if there’s a way that maybe I can use the resources I have to change it a little bit.

And so when I ultimately started working with using blockchain to build digital wallets and things like that, I then made the move over to identification when I realized that that was the root of the problem. And even if I would do something with finance and banking perhaps later on, each woman first needed to have identification to even start to think about collecting any money to their name at all.

IRA FLATOW: Very interesting. So where did the idea for the Etana come in?

ELIZABETH NYAMWANGE: Yeah, so this was a little bit later after I’d come up with the idea of working with biometrics and identification. I initially was just going to see if I could find a nonprofit organization that was doing what I was interested in and then maybe see if I can help out there. But for all the tech startups that I looked at, I found that most of them were, let’s say, trying to bridge that gap of digital identification. But they were doing it through smartphones and apps and Android devices and things that a lot of the women just necessarily didn’t have.

A lot of these women don’t have any sort of internet, electricity, and those are the women that need identification the most. So from that was where I developed this code for it, which was ongoing before. And then, afterwards, that’s when I decided I wanted to make a device itself that would be able to give these women identification without a need for internet or electricity. So that’s where it all came from.

IRA FLATOW: So what does the Etana look like? Is it like a device we would recognize?

ELIZABETH NYAMWANGE: It looks almost like if you would think of a phone maybe 15 years ago. Pretty bulky because a lot of the technology technically had to go– I had to go a little back in time to figure out what exactly would work in these remote situations. It functions almost like a 2G phone, but it looks much, much bigger. And it has a screen, some other attributes on the side for if I ever want to use any different type of biometrics. But I think of it as kind of like a bigger, bulkier phone.

IRA FLATOW: And so how do you work it?

ELIZABETH NYAMWANGE: And so the device itself prompts the woman to enter her fingerprint, enter her identification. And from that, that’s all basically front-end stuff, kind of the same way you would use an app. From that, it takes the fingerprint, and Etana itself converts it into a cryptographic hash. And that hash is then uploaded to a public blockchain server.

And the reason in specific we use blockchain is because it’s immutable. It’s decentralized. It keeps the identification there, but no one can alter it. No one can change it. And that was really important for these women in specific. And from there, for countries that are able to use digital identification, you can then pull the identity, basically, from this central database, and it’s logged as identification.

IRA FLATOW: Elizabeth, talk about this cryptographic hash. What does it do? What’s it for?

ELIZABETH NYAMWANGE: The cryptographic hash is– it could never be duplicated or replaced because it’s honestly just a bunch of nonbinary numbers, so ones and zeros, but organized in such a way that it’s individual to every single person. So there’s never one that could be duplicated between people. And then the way that it’s also sent– think of it like SMS messaging.

So the cryptographic hash is the biometric fingerprint converted into binary. And that is what’s sent through SMS to the public blockchain, which then is altered a little bit. But it keeps the same components of what was then the fingerprint. And it keeps the same exact identification stable in there and secure.

IRA FLATOW: So this is really interesting. So you store your fingerprint up there in blockchain, which is a really, really secure server up there in the cloud. That’s really a cool idea. And how do you use it to prove your identity then?

ELIZABETH NYAMWANGE: For countries that can use digital identification, all you need is something that’s basically verifying that you are who you are– so some type of biometric footprint. And in this case, we use fingerprints. But you can also use something like– and this a little bit more, I guess, complex– but facial recognition, iris sensors, also voice recognition, things like that.

So in countries that you can use digital identification, all of these are stored in a database, which then they can access and verify in their own way or just look at and see you are who you are. But then there’s where other startups can technically help out because they are implementing different ways to verify identification in these low-resource settings but obviously not create identification. So this can be verified in a multitude of different ways. The biggest problem, I guess, was just making sure that these women had identification that could be verified in the first place.

IRA FLATOW: This is really cool. Do you have a prototype yet?

ELIZABETH NYAMWANGE: We do have a prototype. I guess from the money that I’ve won within the past, I think, six-ish months, we’ve been working basically entirely on prototyping since the code was almost entirely developed before. And from that, right now, what we’re trying to do is create a prototype and then hopefully do a research and small pilot in Kenya at the end of this year.

IRA FLATOW: And then how do you go about distributing the device? How do you get the women to use it?

ELIZABETH NYAMWANGE: This is a big part of what our research is going to be when we go and visit these areas in specific. But we are looking for hotspots– places where these women would be able to go a lot– so like churches, schools, markets. And in this, it would be easier for women within a specific community to go and use this device.

The device itself is only $50. That’s the price we’re looking at right now. So in that it wouldn’t be too difficult if you have a large pool of money to be able to spread it out throughout separate different areas. But we want to make it pretty accessible so every woman has an opportunity to see it in at least one of where they venture out locally.

IRA FLATOW: Well, Elizabeth, we wish you great luck and good fortune. And congratulations on winning your prize.

ELIZABETH NYAMWANGE: OK, thank you so much again. Thank you for having me.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. 16-year-old Elizabeth Nyamwange invented a device called Etana, and she was joining us from Byron, Illinois, to tell us about it.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Rasha Aridi is a producer for Science Friday and the inaugural Outrider/Burroughs Wellcome Fund Fellow. She loves stories about weird critters, science adventures, and the intersection of science and history.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.

Mackenzie White was Science Friday’s 2022 AAAS Mass Media Fellow. Her favorite things to talk about are space rocks and her dog, Rocky.