How The West Is Battling COVID-19 And Valley Fever

11:49 minutes

Listen to SciFri’s Lauren Young and Valley Public Radio’s Kerry Klein give a new update on valley fever treatment during the pandemic on KVPR’s Valley Edition on March 12, 2021.

Anna Antonowich is an avid rockhound: She knows where to find petrified wood, amethyst, opals, crystalline clusters of Desert Rose, and Nevada’s other gemstones. In July 2019, Antonowich and her sister were rockhounding in Washoe Lake, southeast of Reno, Nevada, when they encountered gusty winds, strong enough to pelt them with rocks and sand.

Three days later, Antonowich started to feel short of breath. She brushed it off as allergies or a bout of asthma, and decided to go on a planned solo backpacking trip a week later. But as she hiked up nearly 11,000 feet, a feat she can normally take in stride, she felt like she couldn’t breathe.

“I was like, this is crazy. I’m in good physical shape for my age,” says Antonowich, who is 62 years old and a nurse practitioner now working at an oncology clinic in Fort Bragg, California. The day after her backpacking trip, she began to have rigors, where the body gets shaking chills.

“It feels like you have an earthquake in your bones.”

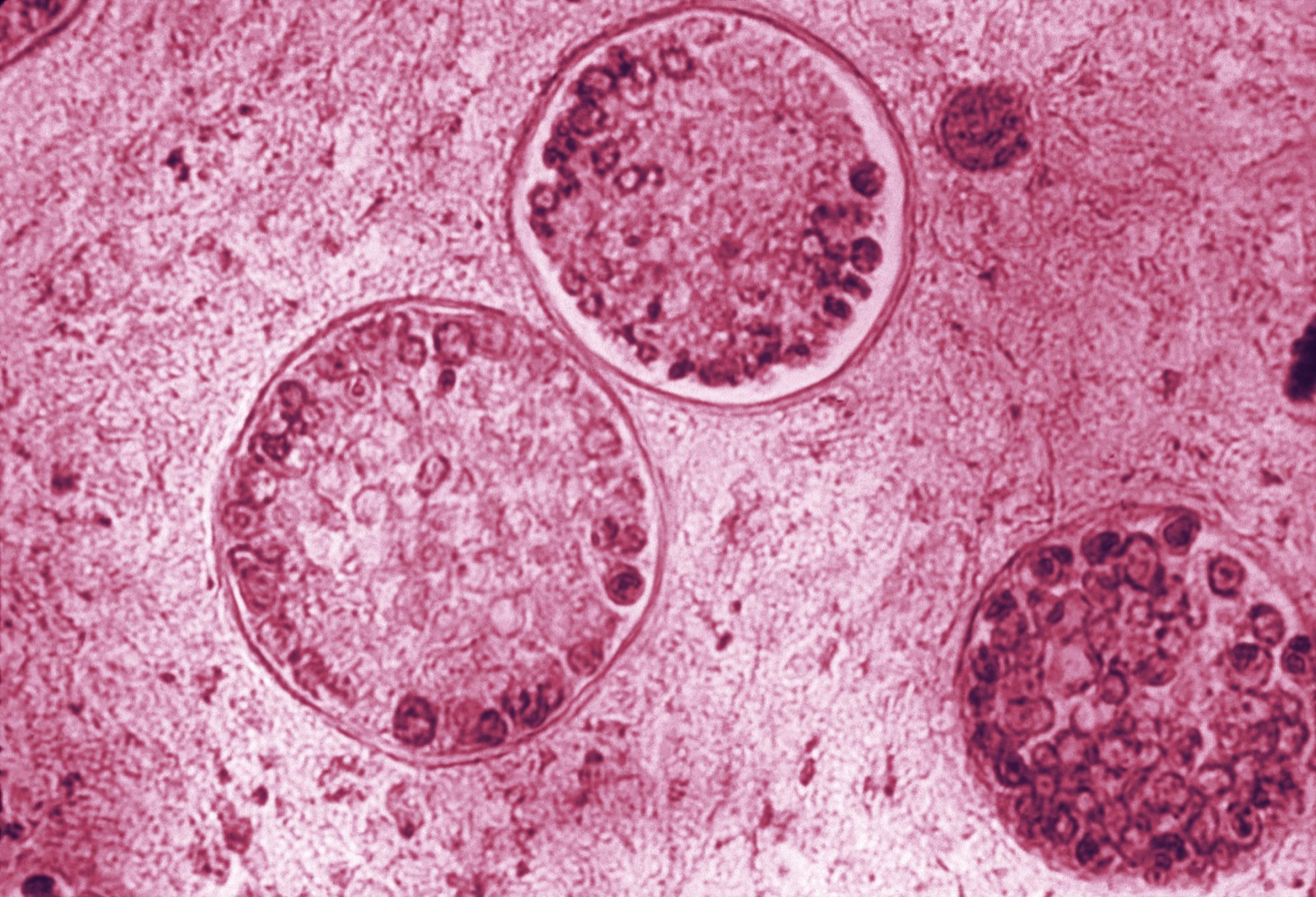

For months, Antonowich experienced a persistent fever, dizziness, and chills. In December 2019, Antonowich was diagnosed with valley fever, a respiratory illness caused by breathing in the fungus Coccidioides, which commonly grows in arid regions of the western United States, Mexico, and Central and South America.

In these desert hot spots, communities are now facing what doctors at Kern Medical’s Valley Fever Institute in Bakersfield, California are calling a “triple threat”: COVID-19, valley fever, and the flu.

Rasha Kuran, infectious diseases physician and associate director of the Valley Fever Institute, says distinguishing between influenza and COVID-19 has been challenging enough. “But for us here, it’s three things instead of two.”

Most valley fever patients have symptoms similar to the cold or flu—some can even clear the disease without knowing they had it at all. But in others, it can manifest into a long term, disseminated illness, where the fungus leaves the lungs and invades the rest of the body. In rare cases, valley fever can cause death. There are certain groups that are at higher risk of getting severe disease, including people who are immunocompromised, Filipino, and Black.

Arthur Charles, a Bakersfield resident who was diagnosed with valley fever in 2017, is one of those high risk patients. Charles is still battling valley fever—continuing to take his antifungal medications—and the pandemic has not made it any easier. Earlier last year, he was scared when one of his sons got COVID-19.

“If he touched the doorknob, my wife was behind him with Clorox and Lysol,” Charles says. “She made sure that I stayed clear of all of this, because the last thing I needed on top of valley fever is COVID-19.”

Listen to Arthur Charles’ full story in an audio feature and special report from Science Friday and KVPR.

Antonowich wasn’t as fortunate. In March of 2020, shortly after she finally recovered from valley fever, she was infected with COVID-19. Her symptoms began with diarrhea, a bad sore throat, and loss of taste and smell. She lives alone and by day three, she says, “I was afraid to go upstairs for the bed, because I may not be able to come back down again.”

Because valley fever is already a commonly misdiagnosed disease, clinicians are now concerned the pandemic could further delay proper diagnosis. Without a diagnostic test, its initial symptoms can be difficult to distinguish from COVID-19 or flu, Kuran says. “Despite being very different, in terms of valley fever being a fungal infection, and influenza and SARS-CoV-2 being viruses, they do present very similarly.”

COVID-19 and valley fever may both be respiratory illnesses, but there are key differences: coronavirus is contagious, valley fever isn’t. The body’s immune system has specific immune cells for handling viral and fungal infections, explains Katrina Hoyer, associate professor at University of California, Merced, who studies valley fever. “There are different immune cells that are important for each of these types of infections, but there’s also a lot of overlap in what those immune responses look like,” she says.

This can also complicate treatment. In Antonowich’s case, she was tested for and diagnosed with COVID-19. She started feeling better, and thought she was in the clear. But then, her symptoms came back.

“Boom, the shortness of breath hit again,” she says. At first, her doctors were uncertain if the symptoms were from the COVID-19 or if the valley fever might have come back. They were able to determine it was COVID-19 and she received further treatment.

Doctors have identified a few symptoms that likely distinguish COVID-19 from valley fever—typically, a sore throat, and loss of smell and taste are indicators of COVID-19. But if you live in a valley fever hot spot, you might want to also rule out a fungal infection by getting tested, says Arash Heidari of Kern Medical’s Valley Fever Institute.

So far, doctors at Kern Medical say that co-infections of valley fever and COVID-19 are rare—the odds of getting both diseases simultaneously are low. While they have had some patients with both infections, the doctors are still trying to understand if patients with severe valley fever are at higher risk of having complications with COVID-19.

“Getting valley fever, at least to our understanding, will not make you more susceptible to get COVID,” Heidari says, but adds that there haven’t been enough cases of co-infection to fully assess what’s going on in the immune system. Doctors are advising patients with histories of valley fever to take extra precautions during the pandemic.

Valley fever numbers are expected to be lower in 2020 than previous years, Heidari adds. That’s because wearing masks and staying indoors to stop the spread of COVID-19 may be helping decrease valley fever infections, too. But Heidari is concerned that the low numbers might also be from data reporting issues and people’s reluctance to go to the doctors’ office to get tested during the pandemic.

“We might get higher than average cases next year, when people come up with complications after the fact.”

Katrina Hoyer at UC Merced has similar concerns. The pandemic has slowed down her valley fever research. She’s shifted toward data analysis that she could still do during the shutdown, but some of her projects have come to a standstill altogether.

“I basically just wrote my progress report to the NIH and had to explain why we have no data for them over the year,” she says. “This is true for pretty much everything that’s not COVID-related. We are not making progress on other diseases right now. I’m concerned about what that’s going to do for the other health problems that we have to deal with when we get through COVID.”

As for Anna Antonowich, she has since recovered from COVID-19, and hasn’t had any additional relapses. However, some of the impacts on her lungs have lingered. “I still have times now where my breath catches. I’ll be talking to a patient, and all of a sudden, I can’t breathe,” Antonowich says.

Her experience with valley fever and COVID-19 has caused her to modify her behavior. “If I’m out in the wind rockhounding, I wear a mask. I’m more careful that way,” Antonowich says, but adds, “I don’t want to live my life in fear of what I’ve been through. As soon as my lungs allow, I’ll be back mountain biking and backpacking.”

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Arthur Charles is a recruiter for the Tampa Bay Rays and a valley fever patient based in Bakersfield, California.

Anna Antonowich is a nurse practitioner at Adventist Health Mendocino Coast in Fort Bragg, California. She is a valley fever and COVID-19 patient.

Katrina Hoyer is an immunologist and associate professor at the University of California, Merced.

Rasha Kuran is a clinical instructor and infectious diseases physician at Kern Medical, and an associate medical director of the Valley Fever Institute. She is based in Bakersfield, California.

Arash Heidari is an infectious diseases physician at Kern Medical and associate medical director of the Valley Fever Institute in Bakersfield, California.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. As you know, for the past year the COVID-19 crisis has taken up much of our attention. The US is still setting record numbers of infections. But COVID can come with complications– in some states, an onslaught of pre-existing diseases. And that’s what’s happening in the West, where doctors and scientists are continuing to battle Valley fever, a disease caused not by a virus, but by a fungus.

Last year, Science Friday producer Lauren Young reported on the patients and communities struggling with Valley fever. You can read her original story up on our website, ScienceFriday.com/ValleyFever. And Lauren is back with an update, the new challenges faced by Valley fever patients and doctors during the pandemic. Welcome back, Lauren.

LAUREN YOUNG: Thanks so much for having me back, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Before we begin, remind us, what is Valley fever?

LAUREN YOUNG: Sure. So Valley fever is caused by breathing in a soil fungus called Coccidioides, or Cocci for short. So this fungus is commonly found in dry regions of the Southwest. Arizona, and California are major hotspots for this disease. In these areas, Valley fever has been around for decades, and anyone can get it, just by breathing it in.

A dust storm or construction can kick up the fungus. Even an earthquake can trigger a Valley fever outbreak. So most of the time, symptoms are pretty similar to the cold or the flu. People can even clear this disease without knowing they had it at all.

But sometimes, Valley fever can be even more severe. The fungus can spread out of the lungs to the rest of the body, and certain groups are at higher risk of getting a severe case. So immunocompromised people, Native Americans, and African-Americans are some of the groups that are more at risk of Valley fever.

And Ira, you might remember, from my original story, I talked to Art Charles. He’s one of those high risk patients. And he told me about his battle with Valley fever.

ART CHARLES: You know, I just felt like I didn’t have a drop of energy at all. That was the first time I’ve ever felt like, I can’t do anything. I just felt helpless. I’ve never felt so weak and so beat in my life.

LAUREN YOUNG: Art lives in Bakersfield, California. And he was diagnosed with Valley fever in 2017. His immune system hasn’t been able to clear it, so he’s still taking antifungal medications. In rare cases, the fungus can even cause death. That’s what happened to Art’s older sister Deborah. She died of Valley fever when Art was only in the sixth grade.

IRA FLATOW: You know, Lauren, this is all sounding so familiar. These Valley fever stories remind me of what some COVID-19 patients are describing.

LAUREN YOUNG: Yeah, right. Well, since reporting the story last year, I couldn’t help but notice some similar themes between Valley fever and COVID-19. So hearing all this, I really wanted to check back in with Art, and see how he was doing during the pandemic.

[PHONE RINGING]

ART CHARLES: Hey Lauren, how are you?

LAUREN YOUNG: It’s really great to hear your voice.

ART CHARLES: Aw, thank you, thank you. I appreciate it.

LAUREN YOUNG: Art first told me about his story back in December of 2019, when neither of us could even imagine the devastation of COVID-19. Art is still dealing with his Valley fever, and the pandemic hasn’t made it any easier. He still has to go to the hospital occasionally to check in on his lungs. But a doctor’s visit that used to take an hour now has a four-hour wait. And he is concerned about getting COVID-19. He had a small scare when one of his sons got COVID earlier last year.

ART CHARLES: My wife was amazing. She’d touch the doorknob. She was behind me with Clorox and with Lysol. And she made sure that I stay clear of all that, because the last thing I needed on top of the Valley fever is COVID-19, you know?

IRA FLATOW: Lauren, how are Art and his son doing now?

LAUREN YOUNG: Thankfully, Art hasn’t gotten COVID-19, and his son has recovered. In fact, Art told me that his son is expecting to have a baby soon. But if you live out west, Valley fever and COVID-19 are both a concern.

There haven’t been many cases of people catching both, thankfully, but it has happened. Anna Antonowich is a nurse practitioner in northern California, and she caught both diseases. In the summer of 2019, she got a pretty bad case of Valley fever– you know, bad shakes, persistent fever, short of breath. She recovered, but a few months later, she got COVID-19, too.

ANNA ANTONOWICH: I realized on day two of my sore throat that this wasn’t a cold. Something else was going on.

LAUREN YOUNG: She got treated for COVID-19, and she thought she was in the clear. But Ira, she got those symptoms again. And at this point, she and her doctors weren’t sure what she had.

ANNA ANTONOWICH: And I’m thinking, oh my God. And so my doctor is like, OK, could this be Valley fever?

LAUREN YOUNG: Her lungs cannot catch a break. So Anna’s pulmonologist was trying to sort out her symptoms. Was it due to Valley fever, or was this still COVID-19?

And her tests came back positive, and it was COVID-19. She’s feeling better now, and no longer has COVID, but some of those side effects are still there. And this is a problem when it comes to Valley fever. It is already a commonly misdiagnosed disease. And the pandemic and the flu season are colliding to make a perfect storm. In Valley fever hotspots, doctors are calling this a triple threat.

RASHA KURAN: People everywhere else, they’ve been dealing with influenza versus COVID. But for us here, it’s three things instead of two.

LAUREN YOUNG: That’s Rasha Kuran. She’s a doctor at Kern Medical’s Valley Fever Institute in Bakersfield, California. And Dr. Kuran says this triple threat is making it trickier to diagnose patients.

RASHA KURAN: And despite being very different in terms of Valley fever being a fungal infection and influenza and SARS-CoV-2 infection are viruses, they do present very similarly. And someone coming in before you do the test, they could be sometimes impossible to tell apart at the beginning. So it really is a challenge.

IRA FLATOW: COVID-19 and Valley fever are both respiratory diseases and have similar symptoms. So, how can doctors distinguish the diseases one from another?

LAUREN YOUNG: Right. Well, as you said, they’re both respiratory illnesses. But there are key differences. COVID-19 is contagious, Valley fever isn’t. You only get Valley fever by breathing it in from the soil or dust. And one is a virus, and the other is a fungus. And they attack the body very differently.

KATRINA HOYER: A fungus has two different life cycles.

LAUREN YOUNG: That’s Katrina Hoyer. She’s an immunologist and professor at UC Merced who studies Valley fever.

KATRINA HOYER: So it has a really small form, the spores, that thins and they get bigger. Because they’re bigger, that makes it harder for the immune cells to deal with them. It’s like trying to take too big of a bite.

Whereas virus particles are very, very tiny. In some ways they’re a little bit easier to deal with. But in other ways, they can hide a little bit better because they’re smaller. So there’s different immune cells that are important for each of these types of infections, but there’s also a lot of overlap in what those responses look like. And the trick is trying to figure out, what are those differences so that you can help the clinician diagnose?

LAUREN YOUNG: So there are many types of immune cells that protect us. But their immune response sometimes can result in the same types of symptoms. Doctors have found a few symptoms that are unique red flags for COVID-19– the sore throat, the loss of smell and taste. But as we know, there’s still a lot that doctors are trying to figure out.

IRA FLATOW: We’ve been hearing about many diseases slipping under the radar during the pandemic. Is this true with Valley fever also?

LAUREN YOUNG: Right now everyone is on the lookout for COVID-19, especially when you talk about respiratory illnesses. And the pandemic could be causing Valley fever to be somewhat underdiagnosed. Arash Heidari is another doctor at Kern Medical’s Valley Fever Institute. And he and his team say co-infection is rare. The odds of getting both are low. But he is trying to make sure that Valley fever isn’t getting overlooked in communities where the fungus is still present.

ARASH HEIDARI: You’ve got to make sure in our community and any other community that might have fungal endemic infections like ours, they need to be tested for that endemic fungal infections, including Valley fever, which is ours.

LAUREN YOUNG: Dr. Heidari wants to be sure that Valley fever patients are being treated for the right disease. He says Valley fever numbers are actually predicted to be lower in general compared to previous years. And all of this mask-wearing and staying indoors to stop the spread of COVID may be helping decrease Valley fever infections too. But again, the doctors say those lower numbers could be because people are going undiagnosed.

ARASH HEIDARI: So all of a sudden, this year, a significant drop to almost [? another ?] half might be probably collection [? data ?] issues. People are probably not willing to go out and be tested. So we might get maybe higher than ever cases next year when people come up with complications after the fact.

LAUREN YOUNG: And Katrina Hoyer at UC Merced has similar concerns. Her research has slowed down. She had just received funding for a Valley fever study on T cells when everything came to a standstill.

KATRINA HOYER: I basically just wrote my progress report to the NIH, and had to explain why we have no data for them over a year. I say this for Valley fever, but this is true for pretty much everything that’s not COVID-related. We are not making progress on other diseases right now. And I’m concerned about what that’s going to do for the other health problems that we have to deal with when we get through COVID.

IRA FLATOW: Right. Really, one can hope that they will get the resources they need, and can get back to their research.

LAUREN YOUNG: Yeah, so researchers are really eager to fully go back to the lab. But they are using this time to ask questions that they can explore from home. So Katrina’s team, for instance, is currently looking at existing data on wildfires and Valley fever. And after the pandemic, she says that the research will still be waiting for them.

And when I talked to Art, it was interesting hearing how Valley fever had, in some ways, prepared him for today’s health crisis. People used to laugh at him for wearing face masks on a dusty day. Now, it’s an everyday reality.

ART CHARLES: It’s kind of funny. I never thought I’d see that day where everyone is wearing masks.

LAUREN YOUNG: Art stopped working at his recreation center job. These days, he’s keeping busy scouting baseball players for the Tampa Bay Rays– with full health safety precautions, of course. And he’s having fun being a grandfather. I did want to ask him if he felt like having Valley fever made him think differently about COVID-19.

ART CHARLES: You know what? I see people dying. When I see people dying, then that’s a real thing to me. So I think people looked at me like, ah, you’re just like that because you’re sick. It’s serious to me. It’s serious to me. I have a grandchild, and I got kids here. And I don’t want to see any of them suffer or have to deal with any of this, ever.

LAUREN YOUNG: For COVID-19 and Valley fever, you hear the numbers of infections and the deaths and about how stretched-out our health care system is. And for me, Art is a reminder of the actual people who are bearing the brunt of all of this, and finding a path forward.

IRA FLATOW: Great story, Lauren. Terrific story.

LAUREN YOUNG: Thanks so much, Ira. I want to thank my guests. Art Charles is a Valley fever patient in Bakersfield, California Anna Antonowich is a nurse practitioner in northern California who had Valley fever and COVID-19. Katrina Hoyer is an Associate Professor of Immunology at UC Merced. And doctors Arash Heidari and Rasha Kuran, infectious disease physicians at Kern Medical Center and Associate Medical Directors of the Valley Fever Institute.

IRA FLATOW: And you can read a lot more of Lauren Young’s stories, her original report. She later interviewed a number of Valley fever patients. You can read the full report and listen to those stories up on our website, ScienceFriday.com/ValleyFever.

Copyright © 2021 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

A selection of Science Friday’s podcasts, teaching guides, and other resources are available in the LabXchange library, a free global science classroom open to every curious mind.

A selection of Science Friday’s podcasts, teaching guides, and other resources are available in the LabXchange library, a free global science classroom open to every curious mind.

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.