Using AI To Help Find Ancient Artifacts In The Great Lakes

10:08 minutes

This article is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story, by Morgan Springer, was originally published by IPR.

At the bottom of Lake Huron there’s a ridge that was once above water. It’s called the Alpena Amberley Ridge and goes from northern Michigan to southern Ontario. Nine thousand years ago, people and animals traveled this corridor. But then the lake rose, and signs of life were submerged.

Archaeologists were skeptical they’d ever find artifacts from that time. But then John O’Shea, an underwater archaeologist based at the University of Michigan, found something. It was an ancient caribou hunting site. O’Shea realized he needed help finding more. The ridge is about 90 miles long, 9 miles wide and 100 feet underwater.

“Underwater research is always like a needle in a haystack,” said O’Shea. “So any clues you can get that help you narrow down and focus … is a real help to us.”

That’s where artificial intelligence comes in. He teamed up with computer scientist Bob Reynolds from Wayne State University, one of the premier people creating archaeological simulations. And Reynolds and his students created a simulation with artificially intelligent caribou to help them make predictions.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Morgan Springer is the editor of the Points North Podcast at Interlochen Public Radio in Interlochen, Michigan.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: And I’m Sophie Bushwick. And now it’s time to check in on the state of science.

[RADIO CALL LETTER MONTAGE]

This is KERN. For WWNO. St. Louis Public Radio. KQED news. Iowa Public Radio news. Local science stories of national significance.

Artificial intelligence is great at detecting patterns, which means its calculations can help predict the future. But AI can also be used to take a look back into the past. That’s exactly what one research team in Michigan is doing, using AI to track the paths of prehistoric caribou. Why? To see where artifacts from ancient hunters may be located. Joining me to talk about this is my guest, Morgan Springer, editor of the Points North podcast at Interlochen Public Radio in Interlochen, Michigan. Welcome to Science Friday.

MORGAN SPRINGER: Thank you so much for having me.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Help me imagine what we’re talking about here before we get to the AI caribou. Where is this land bridge that researchers are so interested in?

MORGAN SPRINGER: Yeah, so it’s at the bottom of Lake Huron, which, for listeners, that don’t know, it’s one of the Great Lakes. It’s on the East side of Michigan. And the official name of the bridge is the Alpena-Amberley Ridge. And it goes from Northern Michigan to Southern Ontario, kind of cutting the lake at a diagonal.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: And what’s the significance of this bridge?

MORGAN SPRINGER: Yeah, so what I’m going to say– it’s going to sound obvious once I say it– but the Great Lakes didn’t always look the way that they do now. If we go back to the Ice Age, the glaciers are receding. And about 10,000 years ago, lake levels were lower than they are today. So that means land that’s now underwater, it was above water then, including this ridge– this land bridge. And it was continuous.

It was this causeway where people and animals could move and migrate back and forth and leave artifacts, presumably. And so then the water levels rise. It comes up. And these artifacts are submerged and remarkably preserved and protected from development. And archaeologists were skeptical that they’d find anything– that this was going to be an opportunity to find artifacts– but they wanted to look anyway.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: And let’s get into the details of this. Why would someone want to research how animals crossed this long-gone path?

MORGAN SPRINGER: Yeah, so John O’Shea, he’s an anthropological archaeologist. And he’s based at the University of Michigan. And he wanted to find something. And so, basically, he came up with an idea for something he thought he could find– something that would have survived being inundated with water about 9,000 years ago. And so one of the things they knew about that time period was that caribou were the main source of food.

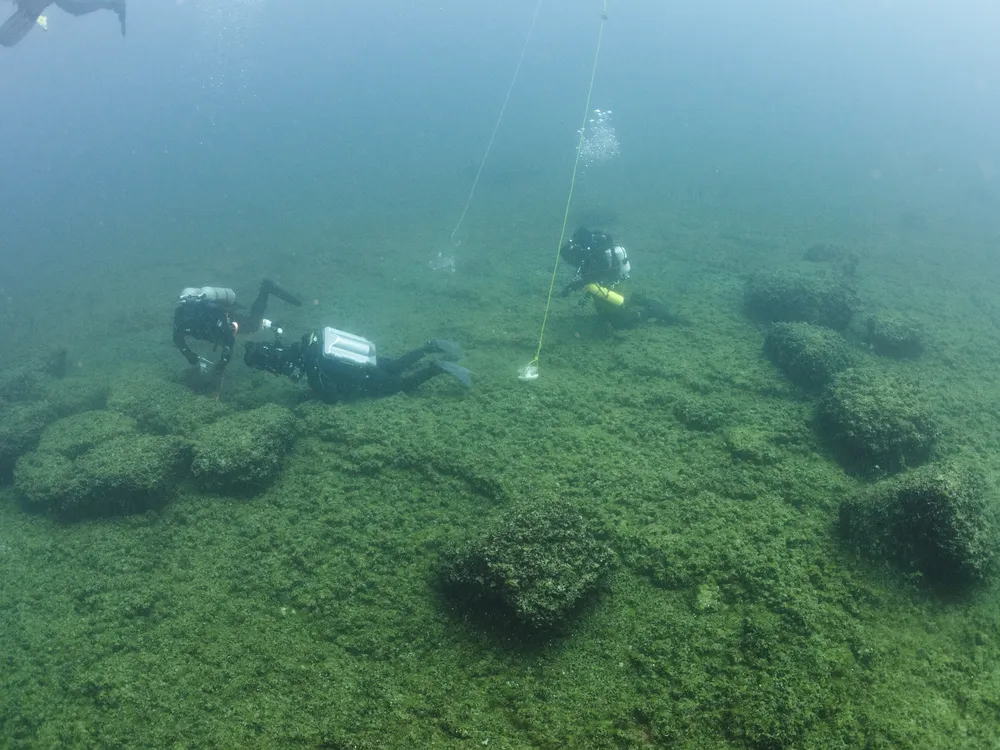

And they also knew that prehistoric hunters made these really cool hunting structures. They’re called drive lanes. And they would guide the caribou to these kill sites. And so John O’Shea, his collaborator, they thought, if they were made of stone back then, maybe we could find them underwater. So it’s all these hypotheticals. But it helps to know where the caribou would go so that they can know where to look for sites.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: So the idea is if the caribou follow a certain path, then humans probably aren’t far behind. And then it’s the humans who are leaving these artifacts.

MORGAN SPRINGER: Exactly.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: And why couldn’t researchers just find these artifacts the old-fashioned way?

MORGAN SPRINGER: Yeah, so, technically, they did find the first one the old-fashioned way, kind of. I mean, they used side scan sonar. I think they had an underwater robot at the time. But there wasn’t any AI. But regardless, the challenge was that Lake Huron is huge. And even though the land bridge offers this concentrated– place this corridor to look– it’s still really long. It’s about 90 miles long. It’s about 9 miles wide. And then on top of that, you’ve got to go 100 feet underwater. And here’s John O’Shea talking about this process.

JOHN O’SHEA: Underwater research is always like a needle in a haystack. So any clues you can get that help you narrow down and focus the kind of places you might look at is a real help to us.

MORGAN SPRINGER: And John happened to know one of the premier people doing archaeological computer simulation. His name is Bob Reynolds. He’s based at Wayne State University. And so their idea was they’ll create a computer model of the land bridge and then use AI to help predict sites.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: And how does this AI actually work? What kind of information were the researchers plugging into the model?

MORGAN SPRINGER: Great question. OK, so the first step is you’ve got to actually build the virtual land bridge, the Alpena-Amberley Ridge. And they use the actual topography. And then they start populating it with digital caribou. And that’s the piece that has the artificial intelligence. So they create these caribou, and they give them instructions. They’re computer algorithms. And the instructions basically tell them how to behave. A really simple one is caribou walk. OK, so the caribou start walking.

And then another simple one is be aware of obstacles and move around them. Don’t bump into rocks or each other. Another one is move in groups and break apart. And they keep refining and refining it until the caribou start behaving more and more like real caribou.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: And what did it look like to watch the AI model in action? I’m picturing a sort of animated video of caribou walking around. But is that what the early models really looked like?

MORGAN SPRINGER: They had some glitches.

[LAUGHTER]

One of the researchers I talked to, she described the caribou look like they were roller skating because they didn’t exactly walk.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: [LAUGHS]

MORGAN SPRINGER: But they’ve kept developing it. And that’s really a whole other story. Now they have an amazing virtual reality where they really look like caribou. But another glitch was– Bob Reynolds, the computer scientist at Wayne State that I mentioned, he talked about this other one glitch that was funny.

BOB REYNOLDS: Literally, the first model we let the herd run across the land bridge. And they did not have edge perception. And so they kept dropping off the sides of the bridge like lemmings.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Oh no! RIP to the AI caribou, I guess.

[LAUGHTER]

MORGAN SPRINGER: I know. I know. And so it’s a perfect example of where they have to introduce a new algorithm. And they basically give the caribou a new instruction, which says, hey, you’ve got to perceive edges. So it’s a lot of trial and error and refining.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: And how well is the AI working today? I mean, have the researchers actually found any real-world evidence based on these computer-generated paths?

MORGAN SPRINGER: Yes, absolutely. They’ve found prehistoric hunting sites. They’ve found artifacts. Ashley Lemke, she’s an anthropological archaeologist also on the team, and she’s currently a professor at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. And here she is.

ASHLEY LEMKE: We get asked as archaeologists, how did you find a site? Or how did you know where to dig? And for me, I can be like, oh, well, artificial intelligence told me, you know?

MORGAN SPRINGER: So how it works is the caribou develop these optimal routes over time. They’re going back and forth and back and forth. And there were a few spots that they went nearly every time. And they call these choke points. And so this was a really obvious place for archaeologists to go and look. And this is just one example of how AI helped. But this one particular choke point led them to this site. They call it Drop 45. It’s the most complex hunting structure found in the Great Lakes to date. And there’s a number of things there. There’s a line of stones guiding caribou to a kill site. There was a fireplace with burnt Earth. Incredible– 9,000 years old.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Wow.

MORGAN SPRINGER: And then there were also these really unusual small tools that were unprecedented for the region. And AI helped them find that, and it saved them time and money.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: And now that these amazing little artifacts– little and large, I guess, artifacts– are being found, what’s next for the team?

MORGAN SPRINGER: Yeah, so keep looking.

[LAUGHTER]

Yes, they’ve found some artifacts, but they’ve just scratched the surface. And with what they’ve found, they’ve started to build an understanding about what the environment might have looked like and how people might have lived. But they’ve also found some totally new and, as I mentioned, unprecedented artifacts. Here’s Ashley Lemke again.

ASHLEY LEMKE: None of this matches the models we had about peoples in this region, which is really fascinating because then you have to go back and be like, all right, well, now we have this new data. What does that mean for what we thought about peoples that were living in the Great Lakes? You kind of have to rewrite the story.

MORGAN SPRINGER: So they keep looking. They keep researching. And they keep rewriting the story.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: And now that it’s been proven that this sort of application for AI works, do you think it will gain traction in the larger scientific community?

MORGAN SPRINGER: You know, I don’t know. I think it should for sure. But Bob Reynolds– he’s the main computer scientist– this is not the only project he’s worked on. So it’s definitely something he’s working on with other archaeologists, other scientists. But it requires a lot of strong collaboration between completely different fields. And I know that Bob specifically, he leans heavily on students at Wayne State to really help make the simulation and the virtual reality come to life.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: That’s all the time we have for now. I’d like to thank my guest, Morgan Springer, editor of the Points North podcast at Interlochen Public Radio in Interlochen, Michigan. Thank you for joining me.

MORGAN SPRINGER: Thank you so much, Sophie.

Copyright © 2023 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.