This video is part of “Breakthrough: Portraits of Women in Science,” a short film anthology from Science Friday and Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) that follows women working at the forefront of their fields. Hear Karletta Chief’s interview on Science Friday, and check out the rest of the Breakthrough series.

Throughout her childhood living in a mountainous region of Arizona, Karletta Chief would make a familiar trek. She would take a 10-gallon white bucket to the local well and pump water up to its brim. Then, lugging the large bucket with her small frame, Chief would carry the water up a hill to her family’s home in Black Mesa, a plateau in the Navajo Nation reservation.

“Being a little kid, it was quite strenuous carrying a big bucket of water,” Chief says.

The Navajo people, or the “Diné” people, have a deep connection to the environment. They see water as a sacred entity. Chief is from the Bitter Water Clan—one of the original clans that derives from the four different types of water the Navajo people came upon. Growing up on the reservation, her family lived off the land and raised livestock, such as sheep, horses, and cattle. But, the community went without electricity and running water.

Early on in her life, Chief became aware of the mining presence in the region. Numerous mines dot the Navajo Nation. The land base—about the size of West Virginia and occupying parts of Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico—is rich with natural resources, luring in industries that extract uranium, coal, oil, and gas. She began to wonder why her family went without common necessities, while coal was pulverized and transported with pristine groundwater to produce energy for large cities, like Las Vegas, Tucson, and Phoenix, Chief explains.

[Meet the killer snail chemist.]

“We had a real sense of conserving water, because it was scarce,” she says. Water is “a real part of just my identity.”

Today, as a hydrologist at the University of Arizona, Chief studies the flow of water through the crannies and channels in soil. Through her research, she tries to better understand how industries impact the environment and people of Navajo Nation.

The Path To Hydrology

Science wasn’t a career Chief had considered when she was young. Despite traversing the forest alongside her father collecting and identifying leaves and plants, it wasn’t until she was in high school that she thought about becoming a scientist and engineer. She went to Stanford to study civil and environmental engineering and completed her degree in 1998, becoming the first in her family to attend college and graduate.

But her roots beckoned her back to Arizona. Her grandmother would tell her in Navajo: “My grandchild, come back to our people.”

“That’s what motivates me in my work as a faculty and extension specialist in environmental science, is the motivation of how I can use my science to come back to my community and help my people,” Chief says.

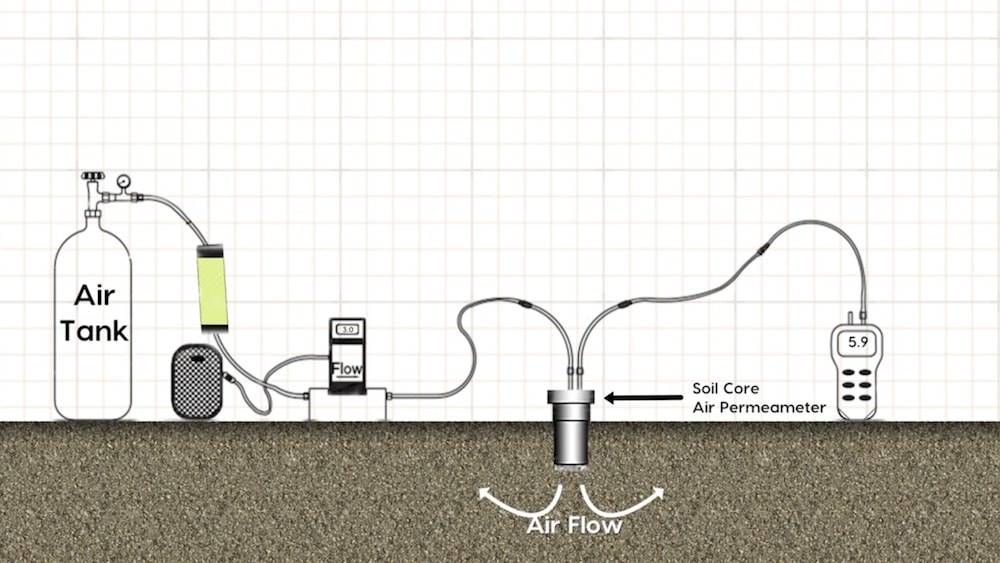

And one of the ways she saw science benefiting her community was through studying the dynamics of water. During her Ph.D. work at the University of Arizona, she invented a new mechanism so scientists could more quickly measure how fast water flows through the soil. Traditionally, hydrologists would use a device that could take up to several hours to take a measurement—but her soil core air permeameter allows for a much more rapid assessment of soil permeability, collecting data in minutes.

Now, as an assistant professor at the University of Arizona, Chief not only teaches students about hydrology, but connects with Indigenous communities to help them understand climate change and how it relates to their livelihoods, economies, and cultural practices—work which put her on the front lines when disaster struck.

A Shock To The River

On August 5, 2015, the naturally clear, pristine Animas River turned a shade of cloudy orange. A crew contracted by the Environmental Protection Agency had been in the process of treating and pumping contaminated water inside the Gold King Mine—an abandoned gold and silver mine outside Silverton, Colorado. But equipment disturbed a plug and unleashed the pressurized water. Three million gallons of acid mine drainage gushed into Cement Creek. The unstoppable torrent of Tang-colored, silty sludge flowed down the creek, through the Animas River and eventually reached the San Juan River, the northern border of the Navajo Nation.

Locals could only watch the spread of the orange plume in horror.

“It was a shock for many people, and people were coming to the river and just crying,” Chief says. “My heart was going out to them thinking about the devastation that they felt as their river was being contaminated. And I just felt a sense of wanting to help.”

For Chief, the spill was personal. Mines have dominated the southwestern region of Colorado since the late 1800s, said Jonathan Thompson, a freelance writer and contributing editor of High Country News, in a Science Friday interview in 2015 when the blowout occurred. “This has been going on really since mining has been here since the 1870s and pretty much most mines leak something out,” he said.

[Gold King, and other abandoned mines plague Colorado.]

Chief’s family had been directly impacted by various past mining operations in Navajo Nation. Once, her grandmother was forced to relocate due to a mine spill. Another time, her family lost 100 sheep after they drank contaminated water.

“It was devastating not only because they lost all their livelihood, but also it was traumatic to our family because we realized how much of an impact the mining could have on our livelihoods.”

It was history repeating itself for Chief. The water from the Gold King Mine created a potentially hazardous mixture: the high acidity dissolved metals from the iron-rich rocks around the area, which caused the orange hue, as well as lead, copper, cadmium, zinc, manganese, and arsenic. If the concentrations of any of these metals spiked high enough, the water could be toxic.

“People were coming to the river and just crying.”

“If there’s metals in these sediment, then that’s a real concern for the people to just do what they do for centuries as part of their culture,” she says. Chief and her team embarked on a one-year study analyzing how the spill may impact the health of the members of the community.

The EPA conducted its standard risk assessment, which only took into account recreational uses of the river, including ingesting the water over a period of time. However, the Navajo people use the river for much more than recreational use, Chief says. Her team surveyed Navajo households along the San Juan River and found that the people use the river in over 400 spiritual, cultural, and agricultural ways—hunting, farming, making baskets out of the riparian reeds, taking sweat baths, and swiping clay on their face for prayers and sunscreen. Members will even put the water in their mouth for prayers, she explains.

Donate To Science Friday

Make an impact with a donation to Science Friday. Your gift will directly support science and journalism.

To determine how much the community members were exposed, Chief’s team measured the levels of the metals in water and soil samples. In the lab, the researchers filtered and processed the water to detect the levels of arsenic and lead. For the sediment, samples had to be pushed out from a PVC pipe, separated into increments, dried, sieved, and then analyzed.

“We found low levels of arsenic and lead that are not of concern to human health,” Chief says.

Safer Waters For The Future

The initial study provided a holistic view of the conditions a year after the Gold King Mine incident, but potential dangers still linger. Spikes in levels of metals in the water do occur, Chief says. The study found elevated levels of manganese in certain concentrated pools, while other research by scientists report that high-flow periods from snowmelt can stir up the sediment and re-suspend the metals, including lead and arsenic, in the river. Complicating matters, the mine continues to leak acid.

“It’s actually something that is a problem daily because acid mine drainage is continually going into the river,” says Chief. “So there’s a need for the Navajo Nation—and many other communities—to constantly monitor their river and their soil to make sure that there are no spikes. And if there are spikes, to protect their people from using the river.”

Chief’s research and her heritage go hand in hand. Her perspectives as a scientist and as a Navajo woman synthesize into her work.

“When you’re a scientist or an engineer, you’re trained to be very objective and to just look at the water mathematically and scientifically, which really takes the person out of that equation,” she says. At the same time, “my identity is water-based [from the Bitter Water Clan]. And so that motivates me to do the work that I do.”

Chief is filled with happiness when she sees her grandmother turn on the faucet and clear, clean water spews out. No more laboring over buckets of water every day.

“In her elder age, it’s wonderful that even though she survived a lot of the impacts negatively from the mine, that now [my grandmother] can have water without worry and have healthy, clean water.”

Video Transcript

KARLETTA CHIEF: When the breach occurred, it was this yellow plume of water. It was just a torrent of acid, mine drainage, going into the river. It was unstoppable. People were coming to the river and just crying. It brought sadness to my heart and I just felt a sense of wanting to figure out a way that I could help the communities being impacted by the spill.

My name is Karletta Chief and I’m a hydrologist. And I study how water moves through the environment. Water– it’s a real part of my identity. The Navajo people, or Diné people, have this deep connection to their environment. I’m from the Bitter Water Clan, one of the four originating clans of the Navajo people. Growing up on the reservation with no running water, no electricity, and with a very strong cultural upbringing of where my family lived off the land, raising livestock, we just lived a simple life.

We live within an area leased to a coal company. One of the big memories I had was how my grandfather, she drank from a contaminated wash, and a hundred of their sheep died. It was traumatic because we realized how much of an impact the mine could have on our livelihoods.

I was very motivated by my desire to help my family and help my community understand the impacts of the mine and minimize those impacts. Nobody in my family had gone to college, but I got accepted to Stanford.

As a PhD student, I designed this soil core air permeameter to measure the permeability of the soil more rapidly. What hydrologists would do is use infiltrometers, measuring how fast the water goes into the soil. And that could take hours. The air permeameter just uses air in minutes.

My grandmother told me to work hard and pursue learning, but she always told me, [SPEAKING NAVAJO] And so I came to the University of Arizona with that motivation.

The Navajo Nation is a rich in natural resources. There are over 2000 mines including uranium, coal, oil, and gas. Extracting and mining, land surface mining, can contaminate water. And so, my goal was to reach out to tribes and address these impacts and the environmental challenges. Many of my elders, though they’re not miners, they passed away from black lung disease and cancer. So I really relate to the impacts of mining on communities and families.

August 5th, 2015. That was the day the Gold King Mine spill had occurred near Silverton, Colorado. Three million gallons of acid mine drain was released into the Animas River. People were going into the river and just watching in horror. The geology of southwestern Colorado has rock that’s rich in iron, as well as other metals. And so when water and oxygen come into contact with metals in the rock, sulfuric acid is generated, and that starts to dissolve the metals, such as arsenic and lead, into the water, creating the acid mine drainage. And we know that arsenic and lead have a health impact at low concentrations for long periods of time.

The risk assessment that was conducted was only addressing the recreational risk. However, the Navajo people use the river in much more ways than recreational. They use the water for spiritual, cultural, ranching. When a spill like this occurs, it’s devastating to the communities that view it as a sacred being. The Navajo living along this river were very concerned about using the water and they had a lot of unanswered questions.

So within the year, we surveyed Navajo households living along the river to ask them how they use the river. And what we found from that is that the Navajo community members use the river in over 400 different ways. They use the reeds for baskets. They’ll put the clay on their face for prayers and for sunscreen. They’ll even put the water in their mouth for prayers. And many more.

And so we needed to understand where are these metals in the environment, where did they go. In order to do that, we needed to take water samples as well as sediment core samples. And so we brought the samples back to the laboratory. The water samples are filtered and for the sediment samples, the sample has to be taken out of this PVC pipe and then categorized according to the depth. Then finally, we can take that sediment and the water sample to an analytical lab to detect arsenic and lead.

For the short term, it was good news in the results that we had. We found from this one year study low levels of arsenic and lead that are not of concern to the human health. However, we did find some spikes in manganese in concentrated pools. And this is something that should be looked at because we do know that manganese leads to some neurological impacts. During the snow melt, the river will increase in flow, and so the metals that are deposited on the sediment will be re-suspended. And we know that the spikes do occur. It’s important to make sure the farmers and the committee members know that they shouldn’t be using the river during these high flow periods.

We report the results to the communities through teach-ins. Sometimes, they ask me, so is it safe? And this is information that we’re empowering the communities to make the decision about using the water on their own. In addition, we train the community members to take samples in areas they were concerned with. Because of that, we were able to directly analyze those samples and address their concerns.

There’s actually a lot more that needs to be done long-term, because acid mine drainage is continually going into the river. Our long-term study actually tries to capture that whole exposure pathways that the Diné people may have as a result of using this river.

So right now, we’re trying to collect sheep samples and corn samples.

We plan to use the air permeameter and the tension infiltrometer to take a closer look at the properties of the soil and get a more complete picture of what’s going on in the sediment through space and time.

Water is very precious. It’s sacred. Growing up, we had a real sense of conserving water because it was scarce. What motivates me and my work is how I can use my science to come back to my community and help my people. And also, try to understand the potential exposure pathways that people have, which can be very diverse. My grandmother charged me with this responsibility. You must come back and help our people. And help our family. It may not be exactly what she envisioned for me, but it’s an honor to bring science to my community.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Credits

A film by Science Friday

Article written by Lauren J. Young

Produced in collaboration with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute

Produced by Emily V. Driscoll and Luke Groskin

Directed by Emily V. Driscoll

Edited by Emily V. Driscoll and Luke Groskin

Filmed by Brandon Swanson

Animations by Luke Groskin

Music by Audio Network

Additional Photos and Video by Hayden Ferguson, Pond5. US Environmental Protection Agency

Project Advisors: Laura A. Helft, Laura Bonetta, Dennis W.C. Liu and Sean B. Carroll – Howard Hughes Medical Institute

Special Thanks to Karletta Chief, Black Mesa United, Shiprock Chapter, Dennis McQuillan, Xiaobo Hou, Janene and Chili Yazzie, Yoshira Ornelas Van Horne, Allison Scott Majure, Danielle Dana, Chistian Skotte, Ariel Zych and Jennifer Fenwick

Science Friday/HHMI © 2017

Related Links

A selection of Science Friday’s podcasts, teaching guides, and other resources are available in the LabXchange library, a free global science classroom open to every curious mind.

A selection of Science Friday’s podcasts, teaching guides, and other resources are available in the LabXchange library, a free global science classroom open to every curious mind.

Meet the Producers and Host

About Emily Driscoll

@emilyvdriscollEmily Driscoll is a science documentary producer in New York, New York. Her production company is BonSci Films.

About Luke Groskin

@lgroskinLuke Groskin is Science Friday’s video producer. He’s on a mission to make you love spiders and other odd creatures.

About Lauren J. Young

@laurenjyoung617Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.