Subscribe to Science Friday

Bearded vultures build giant, elaborate nests that are passed down from generation to generation. And according to a new study, some of these scavengers have collected bits and bobs of human history over the course of centuries. Scientists picked apart 12 vulture nests preserved in Spain and discovered a museum collection’s worth of objects, including a woven sandal that could be more than 700 years old.

Host Flora Lichtman talks with study author Ana Belen Marín-Arroyo, an archeologist who studies ancient humans, about how the nests are giving us a glimpse into vulture culture as well as the lives of the people they lived beside.

Sign Up For The Week In Science Newsletter

Keep up with the week’s essential science news headlines, plus stories that offer extra joy and awe.

Donate To Science Friday

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Segment Guests

Dr. Ana Belen Marín-Arroyo is an archeologist and professor of prehistory at the University of Cantabria in Spain.

Segment Transcript

FLORA LICHTMAN: Hey, it’s Flora Lichtman, and you’re listening to Science Friday.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Today on the podcast, bone-eating vultures that are stashing some surprises in their nests.

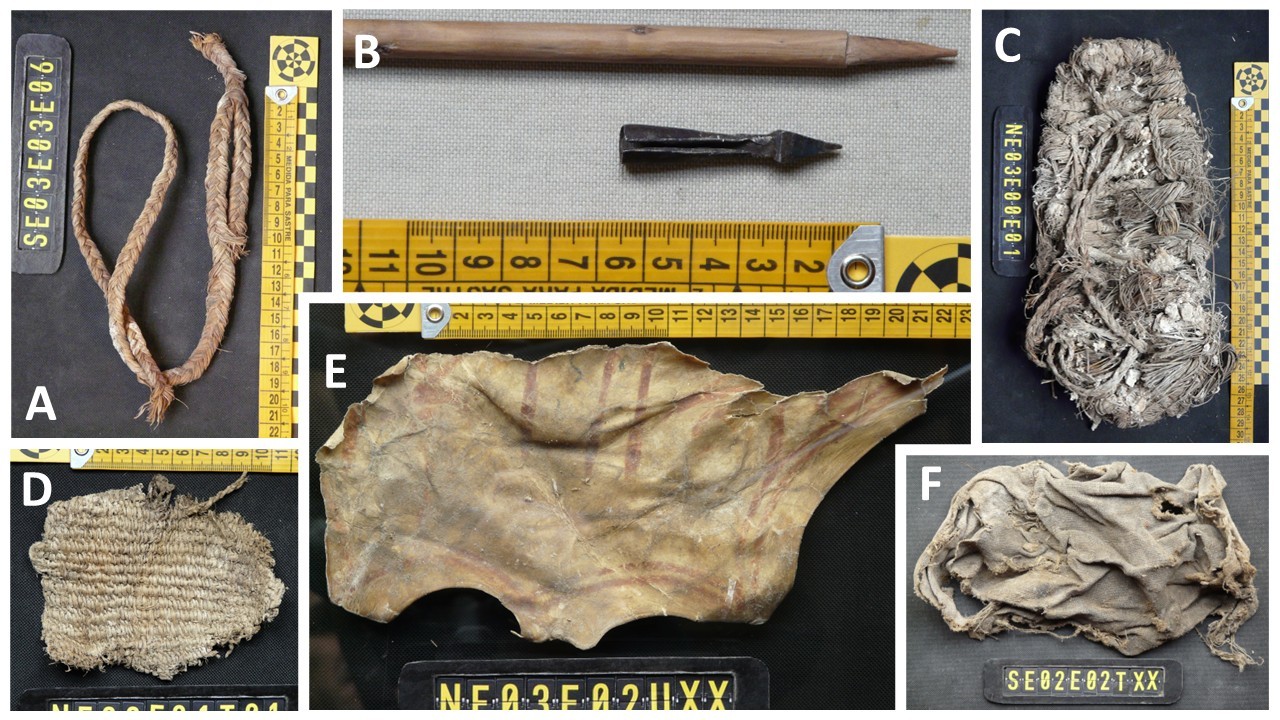

ANA BELEN MARÍN-ARROYO: So we were expecting to find bones and a stick, which is the main element of the nest. But who will be expecting to find an 800-year shoe? Nobody.

FLORA LICHTMAN: The bearded vulture is the only animal on Earth whose main diet is bones and one of the very few to successfully rock a soul patch. But apparently, these vultures aren’t just scavenging skeletons. They’ve been stashing human artifacts in their nests for hundreds of years. Reporting in the journal Ecology, scientists picked apart 12 preserved vulture nests and found a museum collection, hundreds of ancient artifacts, including a woven sandal that could be more than 700 years old.

The nests aren’t just giving us a glimpse into vulture culture, but also the lives of the people they lived beside. Here to dissect the findings is the study author, Dr. Ana Belen Marín-Arroyo, an archaeologist studying ancient human diets at the University of Cantabria in Spain. Ana, welcome to Science Friday.

ANA BELEN MARÍN-ARROYO: Oh, hello. How are you doing?

FLORA LICHTMAN: I’m great. Finding a 700-year-old shoe in a nest seems really surprising to me. But what was it like for you? Were you expecting to find these artifacts?

ANA BELEN MARÍN-ARROYO: Not at all. It was even more surprising for us.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Really?

ANA BELEN MARÍN-ARROYO: Yes, because we didn’t expect it when we were investigating the diet of this bearded vulture. So we were expecting to find bones and a stick, which is the main element of the nest. But who will be expecting to find an 800-years shoe? Nobody.

[LAUGHTER]

FLORA LICHTMAN: Give us a sense. What do these birds look like?

ANA BELEN MARÍN-ARROYO: Oh, it’s lovely. I mean, it’s really nice and really majestic, I will say, because it can be– when the winds are fully open, it can reach 2.4 meters wide. It has a very beautiful orange color. This is very nice. This is very beautiful, the orange color they have in contrast with the black wings.

FLORA LICHTMAN: How big are these nests?

ANA BELEN MARÍN-ARROYO: Well, they are quite massive. So I will say– so. 1.5 meters wide. And it has been accumulated through time. Some of them, they were in deep, like 4 meters.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Wow, OK. So that’s like about 5 feet wide. And they can be 4– did you say 4 meters deep? That’s like over 10 feet deep.

ANA BELEN MARÍN-ARROYO: Yes, they are quite deep. And they have been using through centuries by the bearded vulture.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Wow. OK, so the nests were in use for hundreds of years by vultures.

ANA BELEN MARÍN-ARROYO: Yes, that’s right. We consider that this nest has been accumulated for several centuries. This is what we didn’t know. We knew that these were historical nests, that the bearded vulture left empty or unused for the last 100 years because the species has disappeared in this part of Spain.

But we didn’t know for how many years the desert vulture have been nesting in the same places over and over and over. So no, it wasn’t until we dated by carbon-14. And the most surprising discovery was to find these shoes made on grass that someone used almost 800 years ago. And there are different shoes with different techniques, and they are really, really amazing.

FLORA LICHTMAN: What were some of the other finds? What were the best nest finds?

ANA BELEN MARÍN-ARROYO: [LAUGHS] Well, we access 12 nests. What is the most abundant element in the nest? Sticks, bones, also eggshells, fragments. And the surprising thing for us was to start recovering these iconographic elements like shoes, baskets made with grasses.

Also, we found an arrow with a metal point. Also, we found a leather mask painted with red lines. And we didn’t know which kind of animals’ leather was. So we achieve a proteomic analysis that gave us the result that this leather mask was made on a sheep.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Wow, sheep leather. So it gives you a sense of what the people were doing who were living at the same time as these vultures.

ANA BELEN MARÍN-ARROYO: Yeah, all the material that has been recovered in the nests provide us with various information. So like, what kind of trees were in the environment when they were used by the bearded vulture to make their nests, what kind of animals were living in the landscape.

The eggshells we are planning to analyze will provide us with information about if there was contaminant in the environment, so we will know if there was lead use by hunters in the environment at that time. And obviously, the most interesting thing for us and the most surprising thing is all these various different shoes with different techniques, main on grass.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Yeah, I have to ask about the shoes. Why are birds using these artifacts in their nests? Why is it helpful to have a shoe in your nest?

ANA BELEN MARÍN-ARROYO: This is a very good question. So in order to thermoregulate the temperature in the nest when they put the egg is to bring material to keep warm the nest. But in this case, the bird found these shoes probably abandoned in the nature and considered, hmm, this will be very good to thermoregulate the temperature because it’s thick and stable, and I will take it to my nest.

So we found these different shoes in different nests in different layers, and we dated some of them. And one of the shoes were from the 13th century. So this means they have almost 800 years ago.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Yeah. Wow, 800 years. Yeah.

ANA BELEN MARÍN-ARROYO: And we dated also the fragment of the grass basket. And this is more recent. This is from the 18th century. But here, the most interesting thing is what is coming. Because we have so many shoes to date, we have so many material to analyze that this can still provide us in the future with even more great surprises.

FLORA LICHTMAN: We’ve been talking about their nest building, but we need to spend a moment on their diet. How do they survive on bones?

ANA BELEN MARÍN-ARROYO: Well, this is the most surprising thing of this bearded vulture. 70%, 80% of their diet are composed of bones. This animal is the last one in the trophic chain. So he doesn’t compete with other carnivores or other vultures for getting access to the carrion, so the flesh of the animal carcasses. No. We have videos of him, of his behavior, and he’s just waiting for the others to finish.

And [LAUGHS] when the others have finished, or he doesn’t really compete or fight for food, he selects the bones. And we see that he has a preference for the distal part of the legs, basically the metapodials and the phalanges, because these bones has the highest grease content–

FLORA LICHTMAN: Grease content?

ANA BELEN MARÍN-ARROYO: –on the animal skeleton. So he usually select herbivores’ skeletons, OK? So sheep, goat, deers. This is what the animals they eat, herbivores. So what he does is very curious. So he’s flying. Imagine he’s flying on the nature. And suddenly he saw a carcass and the skeleton of an animal. So he selected the long bones, usually. And what he does is going up, up to 7 to 8 meters and then drop the bone on the mountain on an area where there are stones in order that the impact of the bone on the stones break the bones.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Like seagulls with mussel shells.

ANA BELEN MARÍN-ARROYO: Yes. So in this way, he has this long bone in small pieces, which is easier, easier for him to swallow.

FLORA LICHTMAN: [LAUGHS] Doesn’t seem that easy, though, even in small pieces.

ANA BELEN MARÍN-ARROYO: Well, but this is his behavior. And how he understands that in that way can eat more easily the bones. And his pH is so low that he has the capacity of digesting the bones because neither of us will– even hyenas could really digest the bones. But he does.

FLORA LICHTMAN: The stomach acid just melts those bones.

ANA BELEN MARÍN-ARROYO: Totally–

FLORA LICHTMAN: Wow.

ANA BELEN MARÍN-ARROYO: –melted. And when we see his feces, they are chalk.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Chalk, wow. You write that the bearded vulture nests are natural museums. Tell me about that idea.

ANA BELEN MARÍN-ARROYO: Well, it’s because otherwise we wouldn’t have recovered these human-made artifacts and is opening us a new line of research to investigate all the different vegetable materials and different grasses to make these shoes, to make this basket. So we are planning now to investigate the different techniques used for these humans through time. And obviously, we need to date it, everything, in order for how long this nest has been occupied.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Hmm. I can’t wait to find out.

ANA BELEN MARÍN-ARROYO: Yeah. Me, too. I mean, I am just looking forward to get the funding to send the samples for dating and hear from the results because I think that is going to be really, really cool.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Well, good luck. Study author Dr. Ana Belen Marín-Arroyo and archaeologist and professor at the University of Cantabria in Spain. Ana, thank you so much for joining me today.

ANA BELEN MARÍN-ARROYO: Thank you very much for your interest. And it was a pleasure.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

FLORA LICHTMAN: Today’s episode was produced by Rasha Aridi. I’m Flora Lichtman. Thanks for listening.

Copyright © 2025 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Meet the Producers and Host

About Rasha Aridi

Rasha Aridi is a producer for Science Friday and the inaugural Outrider/Burroughs Wellcome Fund Fellow. She loves stories about weird critters, science adventures, and the intersection of science and history.

About Flora Lichtman

Flora Lichtman is a host of Science Friday. In a previous life, she lived on a research ship where apertivi were served on the top deck, hoisted there via pulley by the ship’s chef.