Seeking Algorithmic Justice In Policing AI

AI researchers and advocates discuss abolishing facial recognition tech—and why gradual reforms aren’t enough.

The recent Black Lives Matter protests have triggered a national reconsideration of how policing in America should operate. Practices are being updated, certain tactics like chokeholds are being banned, and some cities are even undergoing the process of abolishing their police departments.

But the power and message of these protests have led to surprising statements from big tech companies that have contracted out AI and facial recognition programs to police departments and government agencies.

In the last week, IBM said they would no longer develop facial recognition technology and their CEO, Arvind Krishna, condemned the use of facial recognition software in racial profiling and mass surveillance. Amazon and Microsoft said they would stop selling their facial recognition products to police, at least for a while.

But the biases embedded within these profiling systems have persisted for decades. AI researchers Ruha Benjamin, an associate professor of African American studies at Princeton University, and Deborah Raji, a tech fellow at the AI Now Institute of New York University, are all too familiar with the flaws in today’s AI. Facial recognition is “very much a part of the fabric of American life in different ways,” says Raji. “I think a lot of people are not aware of the scale at which it’s deployed.”

Private companies, schools, multiple federal departments, and police stations across the country are making facial recognition a staple tool. When a company or the government has your face, it’s essentially like having your fingerprints, Raji says. But, “we do not upload pictures of our fingerprint to the internet,” she says. “We’re very careful about that data and we should be just as careful about face data.”

Many researchers do not support the technology’s ubiquitous use, especially in a context where an authority figure with little oversight could wield it to dramatically alter Black and Brown people’s lives.

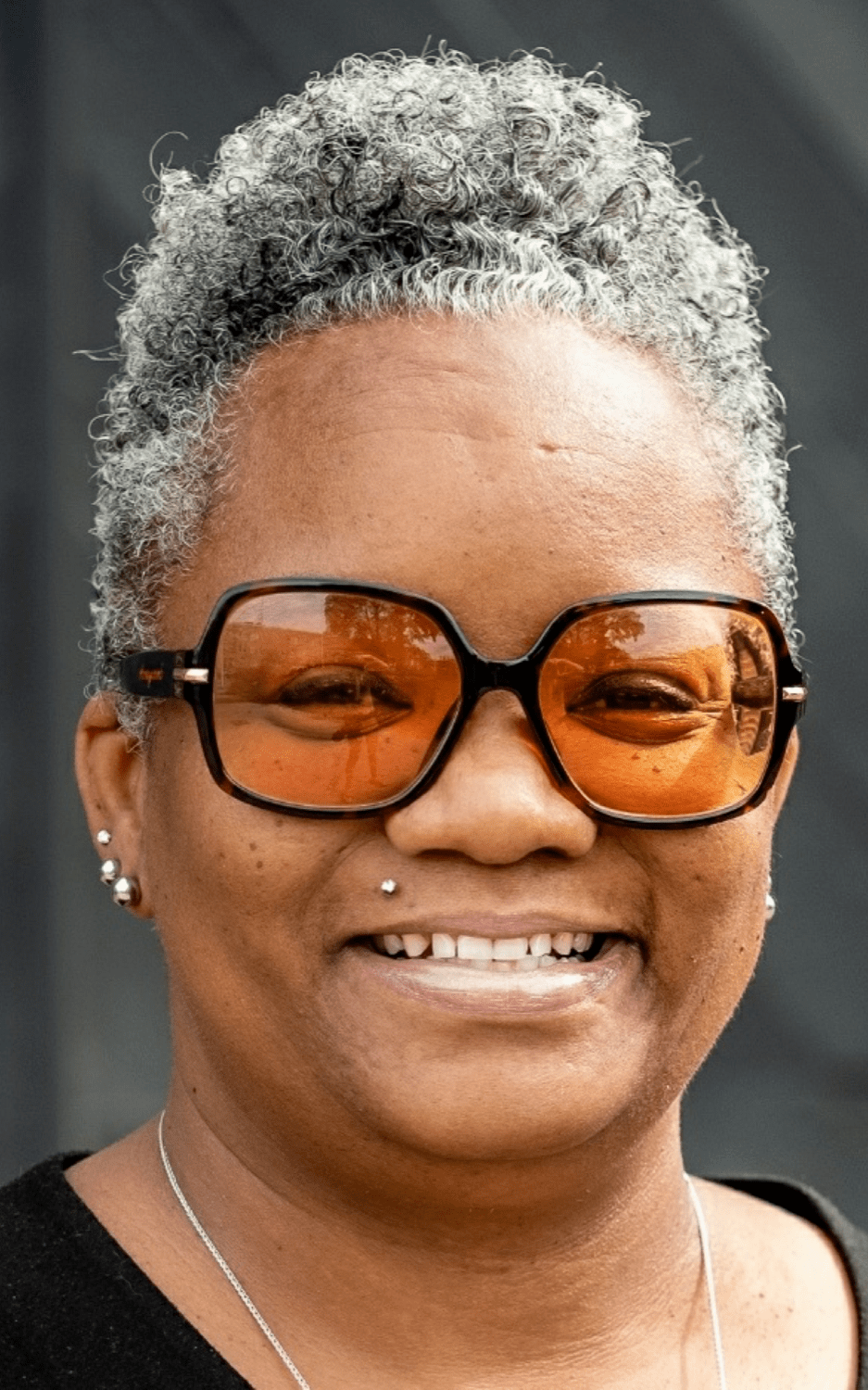

These flawed facial recognition systems have been in use for years. Tawana Petty, the director of the Data Justice Program for the Detroit Community Technology Project and a member of the Detroit Digital Justice Coalition, is pushing back against society’s conflation between surveillance, security, and safety. “These technologies do not make us safe,” she says, “particularly in a predominantly Black city where the technology has proven to unjustly target innocent people through misidentification and predictive policing.”

In 2016, the Detroit police department rolled out a controversial program called Project Green Light, where local businesses could pay the city to install high definition cameras with an associated green light that flashed continually.

Petty describes Detroit’s crime center that receives the live camera footage as “the city’s Batcave.” “You walk in and there are these massive screens that see various aspects of the city.”

Stills from the video images are cross-referenced against 50 million Michigan state drivers license photos, mugshots, and pictures from social media. “Facial recognition is leveraged to flip through all those images and try to make a match,” Petty, who co-authored a report on the program’s practices. The system, which intended to reduce crime, has had the opposite effect for some people, like Petty.

“There are human biases there, human error. There are a lot of folks that look similar,” she says. “The technology is very inaccurate on darker skin tones, particularly women and also children.”

Facial recognition is notoriously bad at identifying Black and Brown faces. A federal study from the National Institute of Standards and Technology found that facial recognition falsely identified Black and Asian faces up to 100 times more than white faces. In 2019, UCLA administrators proposed to install a facial recognition system developed by Amazon to identify if someone coming on campus was an actual student, faculty, or staff.

After student outcry, digital rights nonprofit Fight For The Future fed photos of student athletes and UCLA faculty to Amazon’s AI facial recognition system Rekognition, and cross-referenced those to a mugshot database. Out of 400 photos, “it came back with 58 false positive matches that were largely students of color,” says Benjamin. “So you can imagine that a Black student is walking across campus falsely flagged as an intruder and the police are called.” And in 2018, the American Civil Liberties Union ran Rekognition on images of members of Congress and compared them to a database of mugshots—28 matches were incorrect.

The incorrect matches among people of color is a result of the overuse of datasets that favor White male faces. Raji had experience with that problem up close, when she was working on an applied machine learning team. “I was noticing that a lot of the data sets that I had to work with did not include anyone that looked like me,” she says. “There were not a lot of darker skinned people, there were not a lot of even women.” After her team did an audit of their system and of the facial recognition tools that Amazon was actively selling to ICE and police departments, they found that the systems’ accuracy was 20-30% worse on darker female faces than on lighter male faces, a result that mirrored the outcome of MIT Media Lab’s Gender Shades project, led by Joy Buolamwini. When Raji confronted her former manager about the problem, he didn’t share her concern.

“He was like, this is how it is. It’s so hard to collect data at all.” She was advised to ignore the problem “because it was just too hard.” The systemic attitude that had been ingrained in the field has changed in recent years, and there’s growing advocacy to create more representative datasets.

The glaring inaccuracies and biases, plus the historically fraught relationship between the police and Black communities give Petty pause. She says that police departments are taking the wrong approach to preventing crime: “These residents want to be seen and not watched. If the residents are invested in a way that sees them as fully human, we can reduce crime.”

She points to potential investments that have been proven to reduce crime, like installing more lighting in neighborhoods, providing more recreational space, adequate public school infrastructure, and mental health support. “I just think that [Project Green Light is] a heck of a gamble to take on the lives of residents, especially at a time when even the corporations who are innovating this technology are backing out.”

The big tech companies that have recently placed a moratorium on these technologies have led to a growing conversation about its larger use. Some say it’s not enough to simply include a more diverse dataset, but that society should consider completely banning the use of facial recognition.

“We already know there are a lot of issues around this technology,” says Raji. “Why are we still using it? We should, at minimum, pause its use while we’re having this more nuanced conversation.” Benjamin added: “We’re not questioning simply the scientific merit of these systems, but also their ethical and political merits.”

“We’re thinking about deep-rooted systemic impact that will spread out from neighborhood to neighborhood,” Petty says. “Transforming the hearts and minds of how folks see each other is going to take a little bit of time. It wasn’t done to us overnight. It’s not going to be resolved overnight. But I’m confident that it can happen in my lifetime.”

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Dee Peterschmidt is a producer, host of the podcast Universe of Art, and composes music for Science Friday’s podcasts. Their D&D character is a clumsy bard named Chip Chap Chopman.