These Amazing STEM Educators Are Going Above And Beyond

Here’s the quick and comforting cup of hope you’re looking for—inspiring educators share STEM lessons and tidbits of wisdom.

Things have been pretty bleak this year, especially when it comes to science and education. Government funding has been cut from many scientific programs, students and communities have struggled with inconsistent access to class materials, and educators face challenges with teaching remotely for the foreseeable future. We all need moments of STEM joy right now—a moment to pause and revel in the wonder of discovery.

And that’s why we’re here, to tell you about exceptional educators who are going above and beyond to make science accessible, fun, and engaging for their students. Each week, for the rest of the month, we’ll profile awesome STEM educators and the lessons they created for Science Friday’s Educator Collaborative, our program that works with teachers to build and share free educational resources based on SciFri’s programming.

STEM teachers are the stuff of magic. Their dedication and hard work every school year contributes immensely not only to the young individuals they teach, but to the larger scientific community. We’re hoping to bring some of that magic and tenacity from the classroom out into the world. Maybe they will inspire you, dear reader, to start a career in STEM education, and make a little magic yourself.

All activities will be coming to you through November. Check back in to try them out!

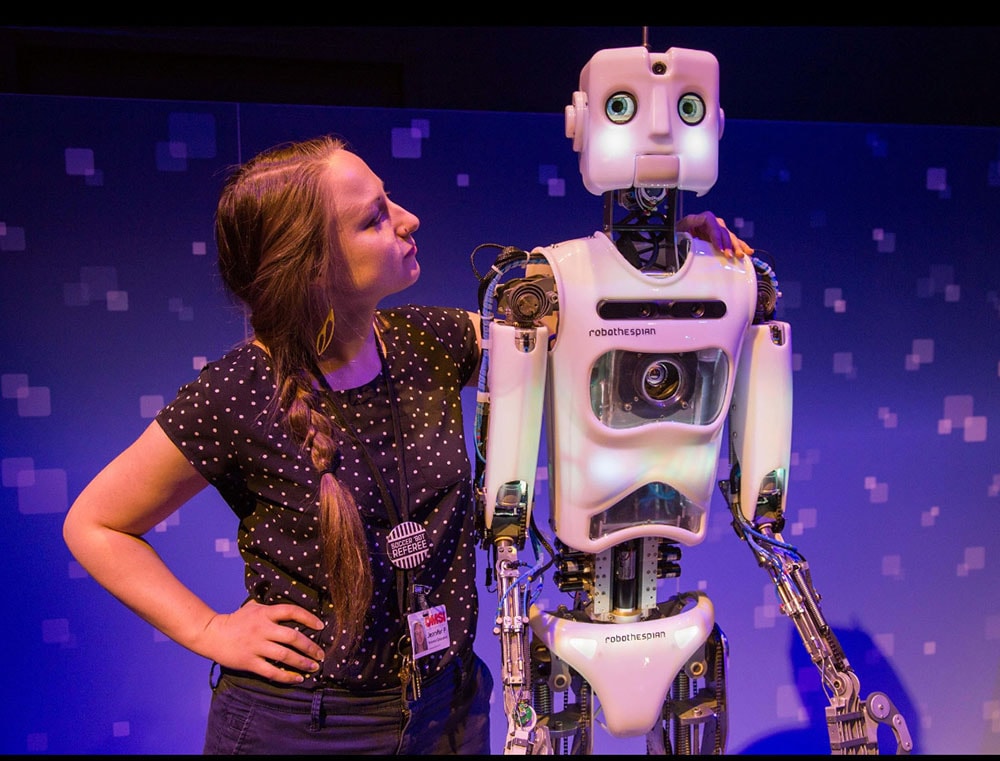

Ever wanted to see a robotic revolution? That’s just one of the incredible interactive exhibits Jennifer Powers creates as a science educator at the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry (OMSI) in Portland. Surprisingly, robot shows weren’t what she thought she’d be doing after studying botany and Spanish in college, but while she was a graduate student researching plant ecology, she began to understand just how large the gap between scientists and the public really was.

“Instead of going into a career as a research scientist, I dropped everything to work in public outreach education,” she says. “Science should be accessible to everyone!”

It was that obsession with accessibility that led Powers to develop an engineering activity to design gloves for a not-so-accessible research locale—space! In an age when current space suit specifications still set limits on who can do a spacewalk, inviting learners to imagine themselves in space, or in any STEM career, is important work.

Powers is reminded of this frequently in her day-to-day routine. An OMSI visitor recently thanked her for showing her grandsons that a female scientist can study and teach about robots, for example. “Her words still make me want to cry,” Powers says. “Representation in science is so important. We have a long way to go, but every little bit, every little robot stage show, matters.”

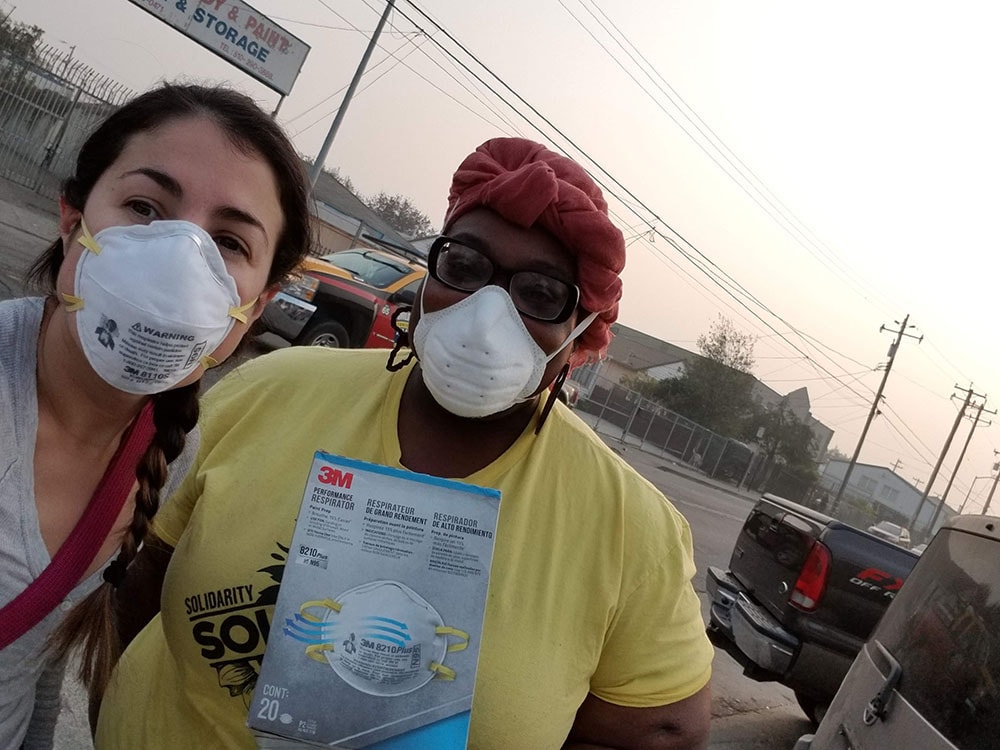

Laura Diaz is a Bay area science teacher, and her deepest science passion is data mapping, which connects issues, social or otherwise, with data—sometimes in map form. While that might not sound like something worth getting all that excited about, it’s core to her work as an educator and activist. “When communities are equipped to address inequities and systems of oppression with data, they can powerfully advocate in a way that is savvy to the system that has been propagating injustices. I strongly feel that education is my calling—and I love using datamaps to engage my students in real-world injustices that happen in their own communities.”

It’s not hard to see this passion in the lesson Diaz has created (which will be available later this month), which uses data mapping to study pollution burden in California. The hope is that this kind of data influences community action and policy changes.

If you ask Diaz to talk about the project, she’ll point you to an even more passionate source: her students. During a recent Science Friday interview with Diaz and three of her students about environmental justice, Diaz let them do most of the talking, an approach very much in line with her teaching philosophy. “I don’t consider myself a disseminator of information. Instead, I view my role as a facilitating co-learner. Adolescents have this fantastic ability to be raw and honest. I just provide them with a foundation of understanding. I strongly believe that they end up teaching me more that I ever can or will.”

Hillary Gutierrez was not your picture of a good science student. “From middle school through college, I was that kid in science class where something always went wrong with my experiments,” she says. But those failures didn’t kill her curiosity for science, a lesson she emphasizes with her students.

Gutierrez has taught elementary school science for 15 years in the North Bay of San Francisco. And she uses her personal scientific misadventures to teach her students that there’s no one way to love science. “When I was in middle school, my teacher pulled me aside before a field trip and told me (and nobody else) not to stick my hand in a ground squirrel hole to catch a squirrel or anything else.”

For Gutierrez, science education was built into her childhood. As a kid, she drilled groundwater wells with her geologist father and visited greenhouses at the university where her mother worked. “Being surrounded by and supported in my scientific curiosity led to a lifelong passion,” she says. But when Gutierrez started teaching elementary school, she was shocked to find out that most of her students didn’t have the same kind of science exposure that she did growing up.

Her animal behavior exploration resource (which will come out later this month) does all of these things—it immerses students in real animal behavior data collection, describes adaptations, and designing puzzle boxes to assess animal intelligence. “My students love art and science, so I make sure to find the time to teach both.”

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Chenille Williams nerds out about soil. A lot.

“It’s so unassuming! People don’t really think about the world under their feet, but there’s a lot of chemistry, physics, and biology involved,” says Williams, the education program coordinator for Richland County Stormwater Management in Columbia, South Carolina.

Williams loves getting into the muddy details about pore spaces, interactions between soil and water, and the ways that soil varies across different ecosystems. Wetland soils are her favorite. “They can come in the most beautiful mottled shades of black and blue, and are very smooth to the touch. I even like their sulfuric smell!”

Williams ran quickly down that nerdy dirt path after hearing a Science Friday radio program about the ways that soil is shifting in our changing climate. Her resource has learners digging up soil samples to examine texture, clay and sand composition, and soil-water interactions before forming predictions about how that soil will change with climate change.

Williams credits her interest in science to her undergraduate college, where students were empowered to be anything they wanted to be. She had been majoring in print journalism at the time when she had an epiphany: “During my sophomore year, I thought, ‘It would be really cool to be a scientist. Oh wait, I can do that!’ It felt like an ‘aha moment’ because I wasn’t used to seeing faces that looked like mine in the science field,” she says.

When Jessica Metz visited California in 2013, she was forced to evacuate from her hotel due to a wildfire. In 2016, wildfires tore through parts of her home state of North Carolina. Since then, she has been watching wildfires across the United States in fear and awe as they have continued to intensify each year.

“How many times can you use the word ‘unprecedented’ before it becomes meaningless?” she asks. These catastrophic natural disasters inspired her to take action in the classroom.

In her work teaching science at New Kituwah Academy in Cherokee, North Carolina, Metz builds lessons about wildfire science, climate change, and Indigenous Ways of Knowing. “How Indigenous people once managed the land for fires is a direct connection to my classroom. It is a clear and dramatic way to teach students about the impacts of climate change.”

Working in the community of the Eastern Band of Cherokee, Metz is continually learning about the connections between Indigenous understandings of how the world works and western science. She’s found those connections in the science of firing a pot within a few degrees for perfection, the nitrogen cycle science of the Three Sisters garden, and the physics in the fletching of an arrow. Metz incorporates this practice in the resource she developed for the collaborative, which explores physics through a study of Cherokee fire pots—pots used by the Eastern Band of Cherokee to transport hot coals and fire for thousands of years.

“These understandings and knowledge, especially when shared through story, are something I never ever get tired of learning and teaching about.”

Ariel Zych was Science Friday’s director of audience. She is a former teacher and scientist who spends her free time making food, watching arthropods, and being outside.

Xochitl Garcia was Science Friday’s K-12 education program manager. She is a former teacher who spends her time cooking, playing board games, and designing science investigations from odds and ends she’s stockpiled in the office (and in various drawers at home).

Dee Peterschmidt is a producer, host of the podcast Universe of Art, and composes music for Science Friday’s podcasts. Their D&D character is a clumsy bard named Chip Chap Chopman.

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.