Just ‘Topia:’ Moving Beyond The Tropes Of Dystopia

Three science fiction and fantasy writers share their thoughts on the risks and rewards of building “other worlds.”

For Cory Doctorow, dystopia doesn’t always mean all hope is lost.

“You can write optimistic disaster stories,” Doctorow, a science fiction writer and author of the recent novel Walkaway, told SciFri in a recent interview. These are stories “where the lights go out and instead of your neighbor coming over with a shotgun, they come over with a covered dish.”

A dystopia is arbitrary. In fantasy and science fiction, technology—whether a failed system or advanced invention—doesn’t necessarily bring a society closer to a dystopia or a utopia.

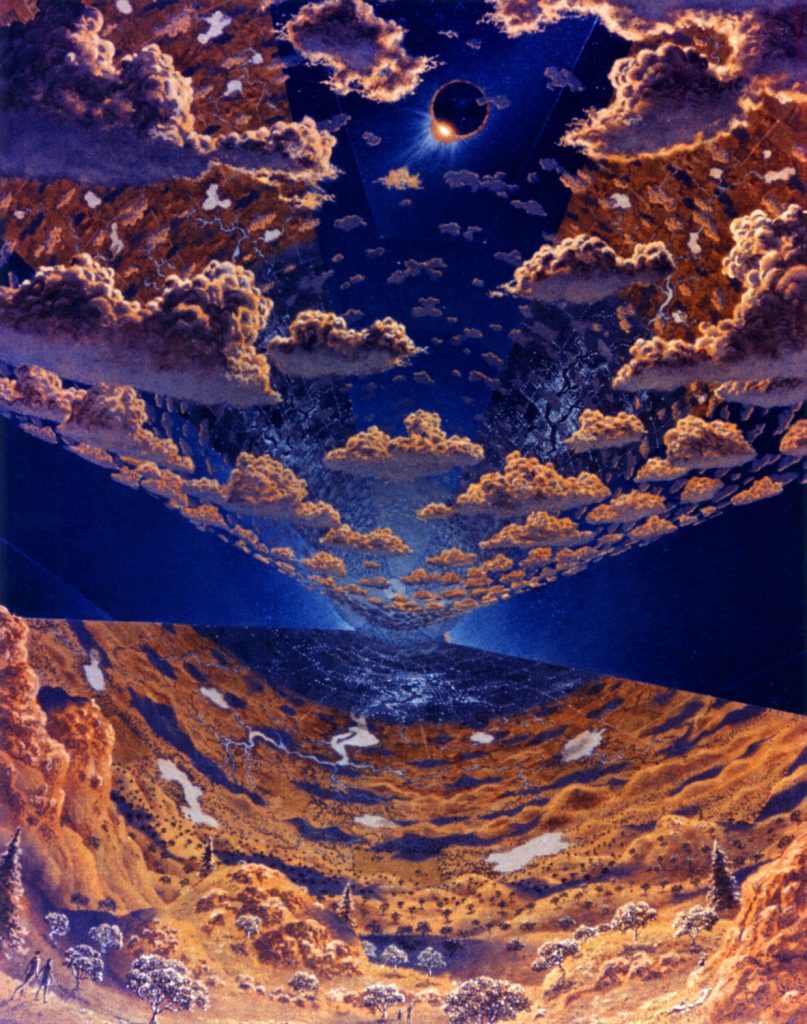

Building “other worlds” allows for more than just depicting what a future or alternate society might look like. For writers, other worlds can be microcosms where they can test aspects of humanity and provide context on today’s issues. In a recent SciFri interview, a panel of science fiction and fantasy writers revealed how they build worlds beyond and outside of our own without falling into the typical dystopian and utopian tropes.

“One of the things that’s interesting about the future is that we can sort of imagine not dystopia, not utopia, but just ‘topia,’” said Annalee Newitz, tech culture editor at Ars Technica and author of the new novel Autonomous. A ‘topia,’ as Newitz described, has a mix of the good and the bad—a world in which some may view as imperfect while others find it prosperous.

A “dystopia” is relative, according to N.K. Jemisin, speculative fiction writer and author of the Broken Earth trilogy. What may seem blissful to some may be apocalyptic to others.

“Depending on who you’re talking to in our society, we are in a dystopia right now,” Jemisin told SciFri.

“One of the things that’s interesting about the future is that we sort imagine not dystopia, not utopia, but just ‘topia.’” — Annalee Newitz

The world of the Broken Earth series is in ruin, damaged by catastrophic earthquakes and volcanoes. But at one point in the history of this universe, society got close to reaching a “solarpunk” utopia. However, a holocaust, which loomed large over the society’s past, came back with a vengeance and festered like an untreated wound.

“Even though you can have this really advanced society you still ultimately got to deal with the ugly brutal primitive baggage of the days back when bigotry and so forth were talked about and were sort of fought,” said Jemisin. “And unfortunately this is a world where the attempt to fight bigotry failed and so they moved on with their technology and their society was rotten at the core.”

Often, technology is mistaken as the catchall solution to problems presented in science fiction or fantasy. But Jemisin says that this is one of the main pitfalls of fantasies and science fiction: allowing the idea that a utopian future—without racism, sexism, or bigotry—can be reached without any work on ourselves.

For instance, in a future world where society has reached lightspeed or established artificial intelligence, some might think that it will lead to the perfect democracy, said Newitz. But social progress is not the same as technological progress.

“We can have spaceships and authoritarian dictatorships,” Newitz said. “We’ll have better earthquake control maybe, but we’ll still have people who are social outcasts.”

Set 125 years in the future, the issues inflicted upon her characters in Autonomous are remedied not by technology but by human empathy.

“My characters are all survivors,” Newitz explained. “They’ve been through incredibly hellish experiences they’ve fought for what they believed in and failed. They’ve screwed up. They’ve been enslaved. They’ve had their minds controlled by corporations. They’ve become addicted to horrible drugs but they make it and they make it by forging alliances with each other.

However, they do not overcome these problems by “becoming rugged individuals who go off into the sunset.”

Rather, “it’s by falling in love with each other, it’s by forming a band of people who can work together to try to make things slightly better than they have been before.”

A disaster, technology failure, or system-wide collapse could lead to dystopia, said Doctorow, but that doesn’t mean the end of society as we know it. In our real world, engineers have designed many machines—from the Titanic to the AT&T phone network crash—that have failed, but humanity has gone on, he said. It’s actually in our best interest to consider disaster scenarios and the outcome.

“Engineers who design systems on the assumption that nothing will ever go wrong do not make well-functioning machines,” he said. Therefore, “it is not dystopian to imagine our collapse.”

In the near-future Earth in Walkway, society has had to give up on the sanctity of privacy, as the rich elite keep close surveillance on civilians. A small group decides to resist and walk away, eventually going on to develop a means to end death—which triggers some violent changes.

Imagining what the future may be like is often locked into either optimism or pessimism, Doctorow said. If the future were truly predictable, there would be no reason to get out of bed, he said. So instead, Doctorow likens writing about future worlds to going to the doctor. The depiction is a diagnostic like the results from a medical exam.

“It’s not dystopian to imagine our collapse.” — Cory Doctorow

If you go to the doctor and she swabs her throat and then puts it in a petri dish for three days and then looks at it under the glass, she’s not trying to figure out like an accurate model of your body,” he said. “She’s trying to make this usefully inaccurate model of your body where like one fact about you is the is the totalizing force in this model of your body in the petri dish.”

This is what Newitz hopes to have captured in Autonomous. The world she created “isn’t really about predicting the future. It’s about sort of talking about the present.” Rather than try to forecast the future in fiction, other worlds can be used to surface the issues and aspects in our world today.

“I think the future is contestable; it depends on what we do,” said Doctorow. “And if the future is contestable then what matters is not will the future be better or worse, but what can we do to make the future more better and less worse.”

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.