The Ribbon Eel

In this excerpt of the book ‘World of Wonders,’ author Aimee Nezhukumatathil describes the life of the colorful ribbon eel—and how these creatures resurface memories of her son.

The following is an excerpt from World of Wonders by Aimee Nezhukumatathil.

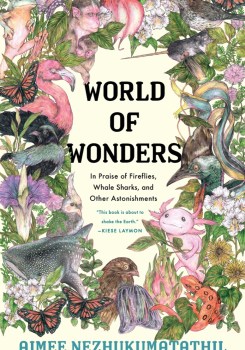

World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Other Astonishments

When this colorful eel, hidden behind coral, detects a guppy swimming nearby and wants to chase down its next snack, it simply unspools itself, as if a piece of ribbon candy has unfolded and softened in the sea. Or no: that’s not right. The wiggle of its body—the undulation to end all undulations—is like my own tongue, excited to tell my husband all the minutiae of a day spent alone with our three-year-old and our infant son, Jasper last baby.

The male ribbon eel’s elongated dorsal fin is a screamy chartreuse-yellow and its belly is an attention-grabbing cobalt. The female is entirely yellow and over a meter long. Ribbon eels are all born jet black males—they are protandric, changing to female only when necessary to reproduce. In the span of a month, these females mate, lay eggs, and die, making it exquisitely rare to see even a single female in the wild. The ribbon eel’s elongated, leaflike “nostrils,” set on each side of its snout, help it detect food scurrying by in the low visibility on the ocean floor. The ribbon eel also has a scruffy yellow goatee on its lower jaw, which stores all its taste buds.

Ribbon eels are mainly content to stay in the same reef hole or coral heap for years, poking their heads out with their mouths ecstatically open as if to say, Wow—look at this spectacular place I call home! Really it’s just drawing water over its gills to help it breathe, though, and that’s how it spends most of its days, most of its brilliant, flat body tucked away. In conditions like these, ribbon eels thrive and live up to twenty years. But the biggest threat to ribbon eels is the home aquarium trade because they don’t survive long in captivity. Inside a tank, they soon stop eating, a silent protest against the ugly hands that lifted their elegant bodies up and into a bag or bucket. Most don’t last even a year.

If while you are scuba diving a ribbon eel happens to wriggle and flick its way over you, you might not even see it—its underbelly is perfectly camouflaged against the refracted sky above. You might feel a small current as it passes, but when you look up: nothing. When I last snorkeled in the South China Sea, I was about three months pregnant and thankful that ribbon eels usually don’t linger near the surface. My stomach dropped at the thought of that ribboned muscle, the movement that mimics a cartoon sound wave. I mostly don’t fear snakes on land, but seeing that mouth wide open would fill me with a tiny terror, as well as joy, to observe a mouth frozen in surprise and delight at each small fish that swims past.

As a baby, my youngest son was famous among our friends and neighbors for constantly opening his wee mouth in shock and surprise and wonder. He never seemed to be tired. If I turned off a lamp, and whispered that it was time to sleep, and slowly let my eyes adjust to the darkness, I would see him still staring at me with eyes as big as malted milk balls in our moonlit room. His pouty mouth parted in a perpetual state of delight. His wispy eyebrows and fine spread of owl-feather hair. The only time he didn’t wear that expression of wonderment was when he blessedly fell asleep, so rare in those early years. But oh—when that finally did happen—how he’d sleep so hard against my chest! We’d both wake in a light sweat, although we were in the middle of a particularly harsh Western New York winter.

And that is how we passed our quiet days at home together during the first cold season of his life, enveloped under blankets while a foot or two of snow fell overnight. Mouths wide open in astonishment at things I’d easily pass over any other time during the busy academic year. I wasn’t able to stay home the semester my eldest was born, so I cherished these slow days with my littlest guy, even though that rascal barely slept more than three hours at a time for his entire. first. two. years. Maybe the only real thing I could do in those blurry months was marvel. Wonder.

How could I forget the constant clock tick after he’d sat up straight in bed between us, face spotlit by the moon, only getting sleepy again if one of us danced with him in the living room or “toured” the house with him in our arms? I had no language for poems then. I barely had language at all, but I could still exclaim, could still show him all the big and small details of this cave full of simple treasures: Here is the laundry room, we wash clothes in this machine. This is a closet, I wonder what is inside—oh, a broom and a vacuum! When you are older you get to play with these things and clean the house! And his favorite: light switches! In every room! The dining room had a dimmer dial, his favorite. I’d save it for last, and he’d kick his footie-covered legs while we slowly approached the dial. But I’d tease him with a quick dash into the kitchen instead: Look at all these spoons in this drawer! Here’s the wedding china we will probably never get to eat off of again! But wait, did we forget this dimmer switch? I wish I knew a baby who knows how to turn this light on! Are YOU that baby?

Perhaps it is because of these whispered nocturnal adventures during the first years of his life that my son’s expressions regularly resemble those of a ribbon eel. Especially here in Mississippi, when our days are mostly spent outside, and it’s all: Mommy! Look at me! Watch this! Mommy, watch me hit a home run! Mommy, did you see that frog? Look! Did you see how high I can jump? A hummingbird! Mommy! When you see a ribbon eel swim, its very expression says, Look! Look at me! Look at that crunchy shrimp!

Perhaps it is because of these whispered nocturnal adventures during the first years of his life that my son’s expressions regularly resemble those of a ribbon eel.

Barring any surprises, this little guy I can still carry on my hip will be our last. Already he is getting too big; I fear this is the last summer I can comfortably carry him around the house. Already he slips out of my arms with such ease. He has finally, finally given up his nocturnal life, and I almost miss it. I miss the winding of our bodies around each other, on those rare occasions when we finally did close our eyes, tangled in such heavy sleep. He is a jolly child, always moving. Almost every picture I’ve taken of him since he could walk captures the same expression of pure jubilation in motion. Mouth open wide and calling out to no one in particular. A blur in a red hoodie. Even now he runs from room to room.

He has slipped from my hip, and my husband and I have to constantly remind him to walk and slow down. But thankfully, he still reaches for my hand when we walk through parking lots or cross the street. When we have family movie nights, he grabs a blanket and jumps into my lap and arranges pillows around us: Look, Mommy! We’re in a cave! He curves his matchstick body against mine so closely I can almost imagine him a toddler again. He has not completely swum away.

From World of Wonders by Aimee Nezhukumatathil (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2020). Copyright © 2020 by Aimee Nezhukumatathil. Reprinted with permission from Milkweed Editions. milkweed.org

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Aimee Nezhukumatathil is a poet, essayist and author of World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Other Astonishments (Milkweed, 2020). She’s also a professor of English at the University of Mississippi in Oxford, Mississippi.