The Origin Of The Word ‘Dinosaur’

Make no bones about this dinosaur story.

Science Diction is a bite-sized podcast about words—and the science stories behind them. Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts, and sign up for our newsletter.

Science Diction is a bite-sized podcast about words—and the science stories behind them. Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts, and sign up for our newsletter.

Note: This piece has been updated. Please find the original article below.

A combination of two Greek words introduced a creature previously unknown to the world.

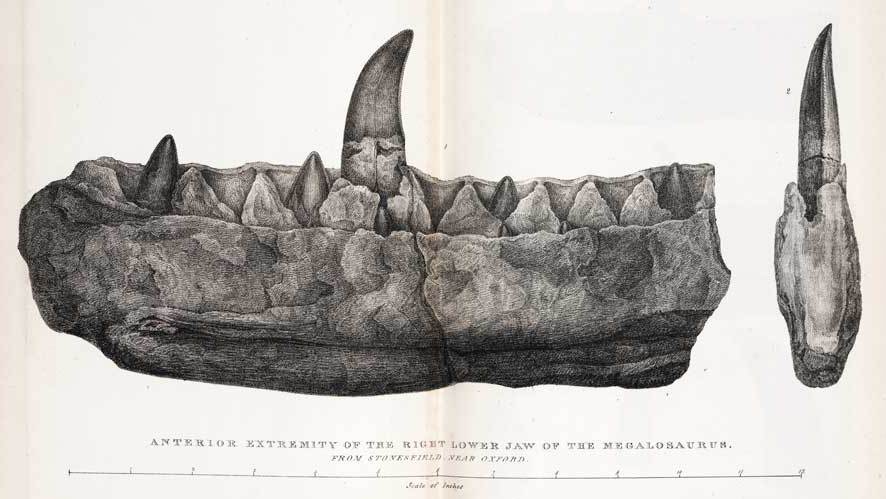

The discovery of dinosaurs didn’t happen all at once—it happened in fits and starts. In fact, larger-than-life bones were unearthed across England and the United States throughout the 19th century. One of these giant fossils appeared to be vertebrae discovered near Oxford, England, a fragment of a lower jaw, and “daggerlike” teeth. A geology professor named William Buckland examined them in 1824, and the source of the bones was eventually called Megalosaurus, named from the Greek words megas, meaning “great,” and sauros, meaning “lizard.”

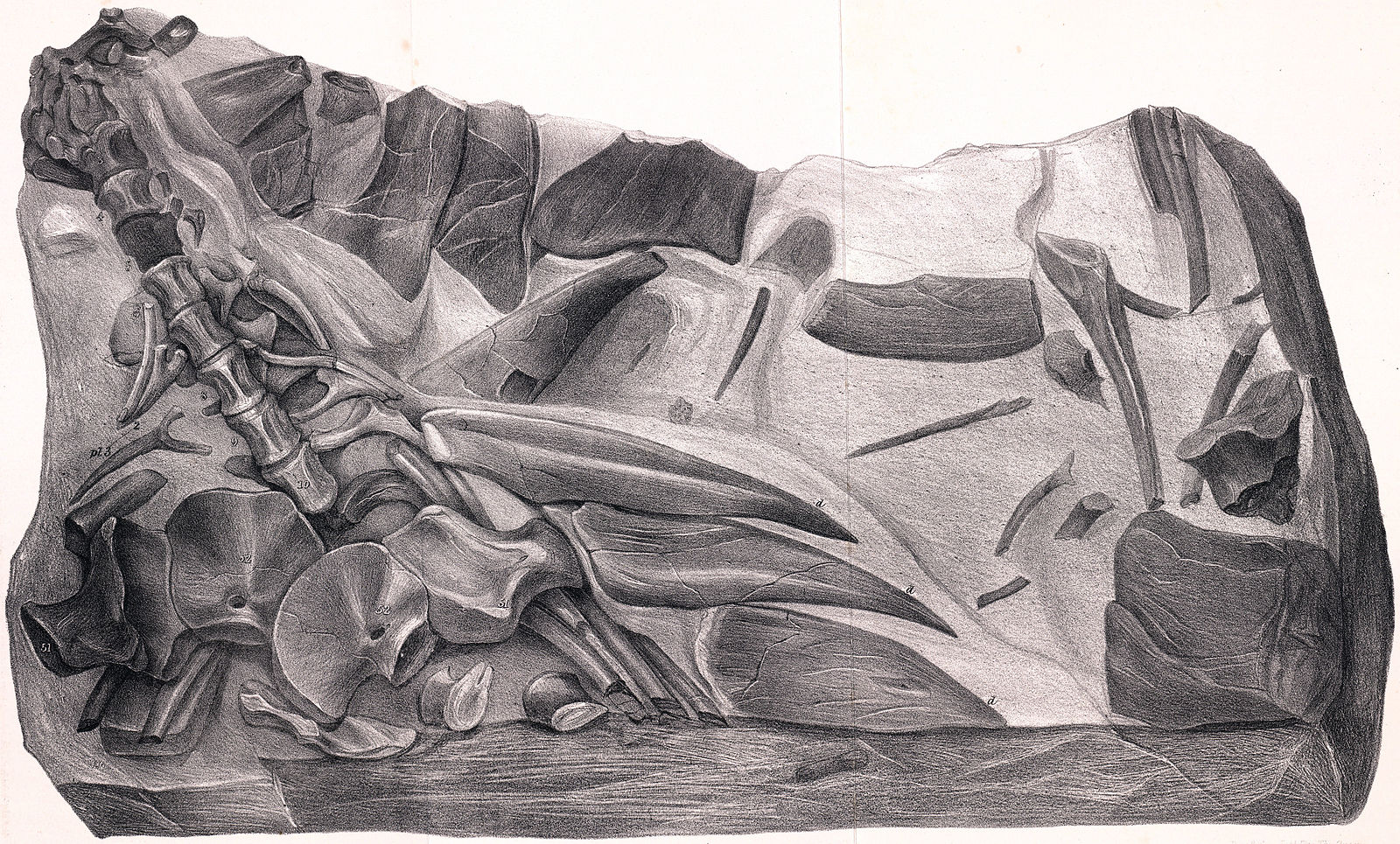

Just one year later, a doctor named Gideon Mantell pondered the teeth and bones of another reptile that had been pulled out of the sandstone in a nearby forest in Sussex. The teeth had serrated edges, were often worn down by chewing, and bore striking resemblance to modern iguana teeth. Mantell named the creature Iguanodon. In 1833, he would describe yet another species—the armored Hylaeosaurus, or a “woodland lizard.”

When Sir Richard Owen, a naturalist and paleontologist, took a look at the three fossils together, he had a stunning realization: Unlike contemporary reptiles, both the Megalosaurus and Iguanodon had five vertebrate at the base of their spine that appeared to have fused together during their lifetime. Owen hypothesized that the same was true of Hylaeosaurus—something that would link the three mysterious species together.

He catalogued his observations in an 1841 edition of Report of the British Association for the Advancement of Science: “The combination of such characters… altogether peculiar among Reptiles… all manifested by creatures far surpassing in size the largest of existing reptiles, will, it is presumed, be deemed sufficient ground for establishing a distinct tribe or sub-order of Saurian Reptiles, for which I would propose the name of Dinosauria.”

Owen had compounded two Greek words: deinos, which means “horrible” or “fearful,” and the previously used sauros. The result: A terrifying lizard.

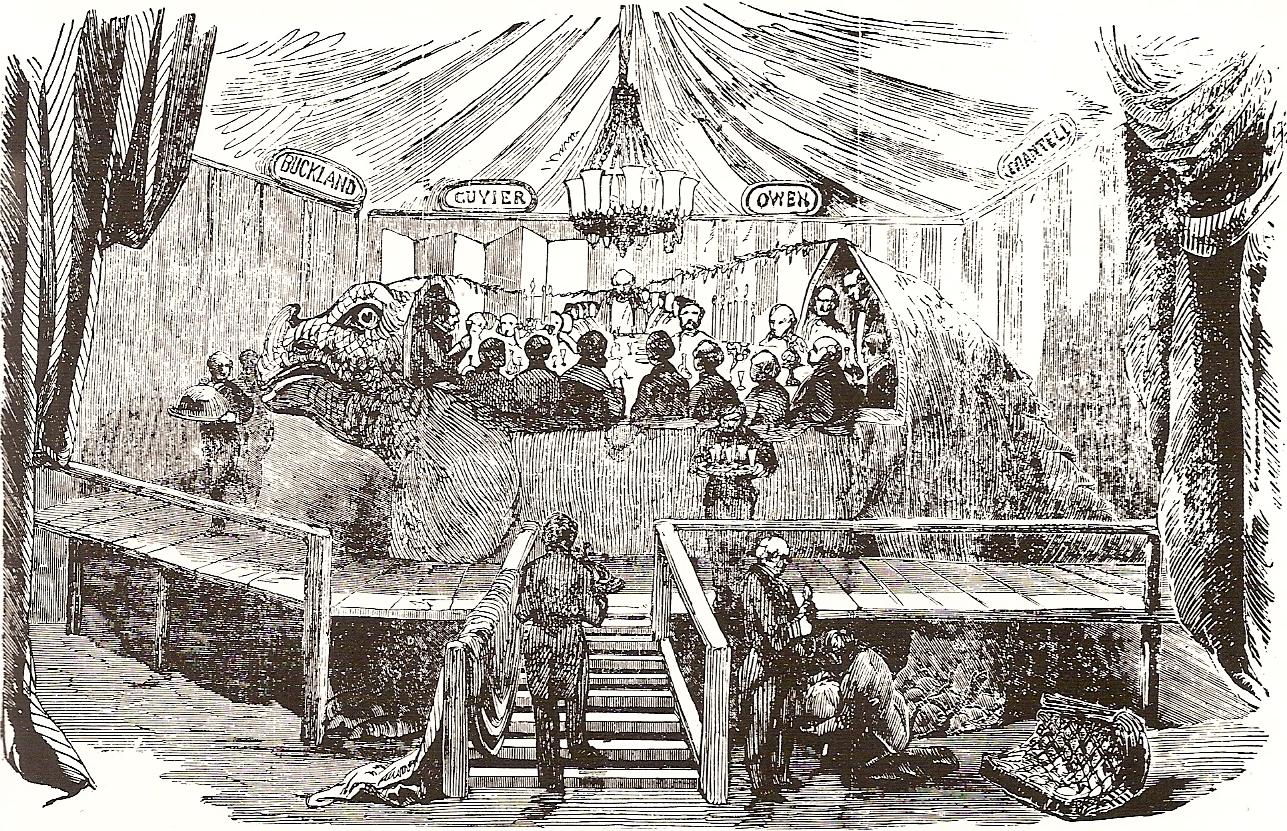

The lizards were not terrifying enough, however, to prevent Owen from eating dinner inside a dinosaur. In the early 1850s, the sculptor and natural history artist Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins was commissioned to construct a series of sculptures for the opening of a park outside London’s iconic Crystal Palace, which was home to exhibitions and festivals. Hawkins decided to create a herd of lifesize, three-dimensional dinosaurs for the park—with Owen as his advisor.

For such a larger-than-life project, an equivocal publicity stunt was due. Hawkins invited a group of scientists, academics, editors, and influential men for dinner… inside the mold of an Iguanodon. On New Year’s Eve 1853, 11 of the guests sat inside the dinosaur’s “shell.” At the head of the table, right inside the noggin of the giant Iguanodon, was Owen.

But the dinosaurs would outlive the man who gave them their name. When a fire destroyed the Crystal Palace in 1936, they were abandoned as foliage from the ruined grounds obscured them, and they were exposed to the elements. While advancements in paleontology rendered the models blatantly scientifically inaccurate, the statues were eventually listed as being historically relevant, and the remaining dinosaurs were fully restored in 2002. Today, 29 dinosaur statues remain, housed in the restored Crystal Palace Park in London—including the Iguanodon.

Original piece by Howard Markel, published July 6, 2015:

Everybody likes a good dinosaur story, but one of the best dinosaur stories of them all centers on the man who gave these remarkably extinct beasts their name.

He was Sir Richard Owen (1804-1892). In his day, Sir Richard was a celebrated naturalist and founder of the British Museum of Natural History. Some time around 1839, Sir Richard began studying the bony remains of extinct races of reptiles: the carnivorous Megalosaurus, the herbivorous Iguanodon, and the armored Hylaeosaurus.

To name these creatures, Owen compounded two Greek words: δεινÏŒς (deinós), which means horrible or fearful, and σαῦρος (saûros), or lizard. The result was dinosaurian or dinosaurs. For Owen, the reptiles were “terrible” or “terribly fearful,” a term which still holds great resonance even when staring at their long since petrified skeletons within the safe confines of a 21st century museum.

The word dinosaur made its literary debut in a long monograph Owen wrote called “Report on British Reptiles, Part II,” for an 1841 issue of the Report of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. In 1873, the term appeared again in The Story of Earth and Man, a popular natural history text by J.W. Dawson. Following more and more unearthing of these creatures’ remains, the use of “dinosaur” only grew more entrenched in both the fossil record and our popular imaginations.

The Oxford English Dictionary also describes the origin of the slang use of dinosaur, which refers to someone or something that has failed to adapt to a new environment or circumstances. The O.E.D. notes that the term used in that sense first appeared in the Manchester Guardian (now known as The Guardian) on April 3, 1952. This reference is actually incorrect, however: The article, written by the famed British journalist Alistair Cooke, instead appeared in the newspaper on March 31, 1952. What’s more, the word was used in a quote from a speech by Harry Truman at the Jefferson-Jackson Day Dinner in Washington D.C. on March 29, 1952. Criticizing the G.O.P., “Give ‘Em Hell Harry” railed: “This is the kind of dinosaur school of Republican strategy. They want to go back to prehistoric times…this…would only get the dinosaur vote—and there are not many of them left, except over at the Smithsonian.”

Regardless of its origins, it is never a compliment to be called a dinosaur by a younger colleague or relative.

But let’s get back to the creator of the word dinosaur, Sir Richard. Although a contemporary of Charles Darwin (1809-1882), the influential Owen was a loud critic of Darwin’s transformative book, On the Origin of Species.

Sir Richard is credited by many science historians with writing a devastatingly snarky—and anonymous—review of Darwin’s scientific masterpiece. The scathing essay appeared in the April 1860 issue of the venerable Edinburgh Review. Although Owen did believe in evolution of a sort, he found Darwin’s explanation to be simplistic and incomplete.

[Why do we want to protect some robots, but harm others?]

Owen also took Darwin to task for not respecting the views of “creationists” and making them look one-dimensional and naïve. Initially, the review gravely hurt Darwin’s psyche as he worried about its impact on his scholarly reputation. But with time, success, and more reproducible scientific evidence, Darwin’s career soared.

The two never stopped bickering and carping about the other. But Owen was also involved in controversies with many of his other colleagues. For instance, several researchers accused him of claiming their scientific discoveries as his own.

Britain honored the great Darwin by erecting his statue in a place of pride in the marble and brick cathedral that serves as the British Museum of Natural History in South Kensington, London. Owen’s statue replaced Darwin’s position in 1927 (with the Darwin piece being shunted aside to a secondary room). But as The Atlantic Monthly reported in 2009, on the occasion of the bicentennial of his birth and the 150th birthday of the publication of On the Origin of Species, Charles Darwin was rightfully restored to the main landing of the grand staircase.

In the end, of course, it is Darwin whom we remember, while Owen has been relegated to the so-called dustbin of history. Sir Richard may have “invented” the dinosaur and even dominated the conduct of the world famous British Museum of Natural History, but it was Darwin who changed the world. Which begs the question: Who’s the dinosaur now?

Editor’s note: This article previously stated that Richard Owen was forced to walk past the statue of Charles Darwin every morning as he climbed the stairs to his office in the Museum of Natural History. This is not accurate, as Owen retired from the museum in 1884, before the statue was erected. The sentence has been removed, and we regret the error.

In addition, this article has been updated to include additional information about the etymological and historical origins of the word ‘dinosaur,’ as well as the anecdote about the dinner inside the ‘Iguanodon’ mold.

Howard Markel, M.D., Ph.D. is a professor of the History of Medicine at the University of Michigan. An elected member of the National Academy of Medicine, he is editor-in-chief of the Milbank Quarterly and a Guggenheim fellow.

Johanna Mayer is a podcast producer and hosted Science Diction from Science Friday. When she’s not working, she’s probably baking a fruit pie. Cherry’s her specialty, but she whips up a mean rhubarb streusel as well.