A Tiny Fungus With A Big Impact

27:02 minutes

Hawaii’s primary forest tree, the ʻōhiʻa lehua, is under attack by a microscopic fungus—bringing an ecological change to Hawaii that could reshape the islands’ landscape. The tree, with blossoms that resemble a red explosion of fireworks, is one of the forest’s keystone canopy trees.

[Will a new education program in Utah convince fewer people to forego vaccines?]

USDA Agricultural Research Service plant pathologist Lisa Keith is working to track down the fungal culprit, to slow its spread across the Big Island, and to try to determine whether resistant strains of the ʻōhiʻa lehua tree exist. Greg Asner, an ecologist at the Carnegie Institution for Science, joins the conversation to talk about mapping tree death from the skies, with sophisticated camera and chemical sensing equipment. Check out some pictures from the process below.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow, coming to you from the Kahilu theater in Waimea, Hawaii.

[APPLAUSE]

The lava flows southeast of here are reshaping the island we’re sitting on, even as we speak. But there’s another stealthier, less flashy force that could affect the island’s landscape in the decades to come. And I’m talking about a microscopic fungus. It’s attacking one of the forest keystone canopy trees, the ohi’a lehua, whose blossoms resemble a red explosion of fireworks.

And as this fungal villain hopscotches across the big island, my next guests are doing the sleuthing to predict where it’s going to go next and how to stop it. Greg Asner is an ecologist at the Carnegie Institution for Science in Palo Alto and here in Volcano. Welcome to Science Friday.

GREG ASNER: Great to be back. Thanks.

[APPLAUSE]

IRA FLATOW: Lisa Keith is a research plant pathologist at the USDA Agricultural Research Service in Hilo. Welcome to Science Friday.

LISA KEITH: Thank you very much. Great to be here.

IRA FLATOW: All right, Lisa. Set the scene for us. How bad is it going here? Listeners, especially across the world, may not be familiar with what’s happening.

LISA KEITH: Well, the disease we’re talking about is Rapid Ohi’a Death. When we discovered it in 2014, I think we thought there would be no forests left.

IRA FLATOW: That bad?

LISA KEITH: Yes. It looked very dire at first. But I’m here to say there’s lots of hope and lots of healthy forests still existing. So while it is definitely harsh plant pathogens, with a group, a good team, it’s definitely being managed.

[APPLAUSE]

IRA FLATOW: Greg, you’re nodding up and down. You’re in agreement that all is not lost here.

GREG ASNER: Oh, no. There’s a lot of hope, a lot of good effort. Hundreds of scientists have come together to do this.

IRA FLATOW: I’ve heard this described as the Ebola of tree diseases. Is that right?

LISA KEITH: That was an early quote by our friend, Flint, yes. He has many of those. But definitely, like Greg mentioned, there’s a lot of healthy forest. There was a lot of studies testing seedlings for resistance to try to get a picture of what’s ahead. It’s very hopeful. Even in areas where 90%-plus mortality is seen, there are trees existing. So it looks a lot better than we thought.

IRA FLATOW: To give a broader picture, we have a slide, actually, of what the devastation looks like, all those dead trees. But they’re not all dead.

LISA KEITH: That’s correct. That’s the bright spot– that you see healthy amongst this mortality.

IRA FLATOW: And Greg, you’re involved in a study that actually looks for these trees from a plane. How do you do that?

GREG ASNER: Well, there’s the plane on the screen. It’s a unique aircraft. It’s our airborne laboratory that we use for flying over forests or whatever we’re flying.

That’s the inside of the laboratory. It’s a high-tech environment, supercomputing instruments that can see the chemicals in these trees. And from those chemical measurements, we can tell you if the tree is healthy or sick. And so we’ve been flying over these ohi’a forests and determining where are the sick ones.

IRA FLATOW: So you wind up with sort of an aerial map, a picture of what the plane sees.

GREG ASNER: That’s right. This is a view on the screen of a single or maybe just a few of the sick trees in brown. And the gray ones are the ones that have already passed away. They died. And the green ones are the ones that are still making it. So we fly over. We find each of these in the forest. And we make maps.

IRA FLATOW: If I didn’t know the scale of this picture, I’d think it was a head of broccoli.

GREG ASNER: Right. Those are hundreds of trees right there. And there are a lot of ohi’a trees out there on this island.

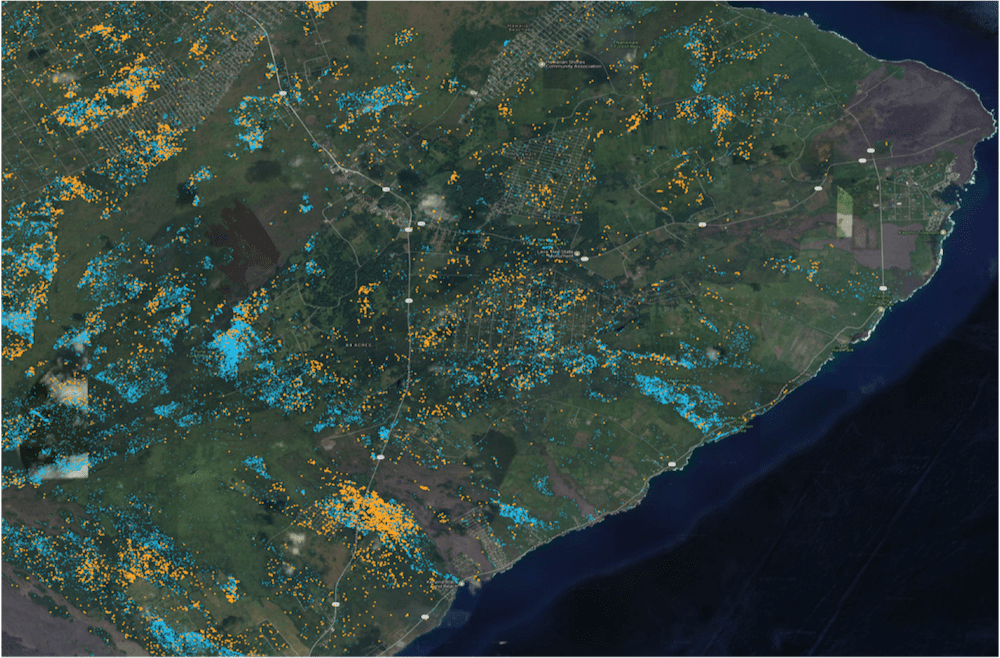

IRA FLATOW: If we zoom out a bit, you can actually see a forest covered in blue and orange dots. What do those dots mean?

GREG ASNER: This is the southeast corner of the big island. And the blue dots are areas where the trees have already died. And the orange or yellow dots as you see them are the trees that are sick at the time of over flight. So this is a part of the island that was particularly heavily impacted by this pathogen.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Keith, how does the disease spread? How does it move from tree to tree, I guess is what I’m asking?

LISA KEITH: That’s a great question. And that definitely is the subject of much study– how it gets into the tree, these fungi. So actually, we’re talking about two new species of fungi of the genera Ceratocystis. And they need wounds to get in. So that could be something caused by hurricane-force winds. Or that could actually be something where you weed whack the trunk of your tree.

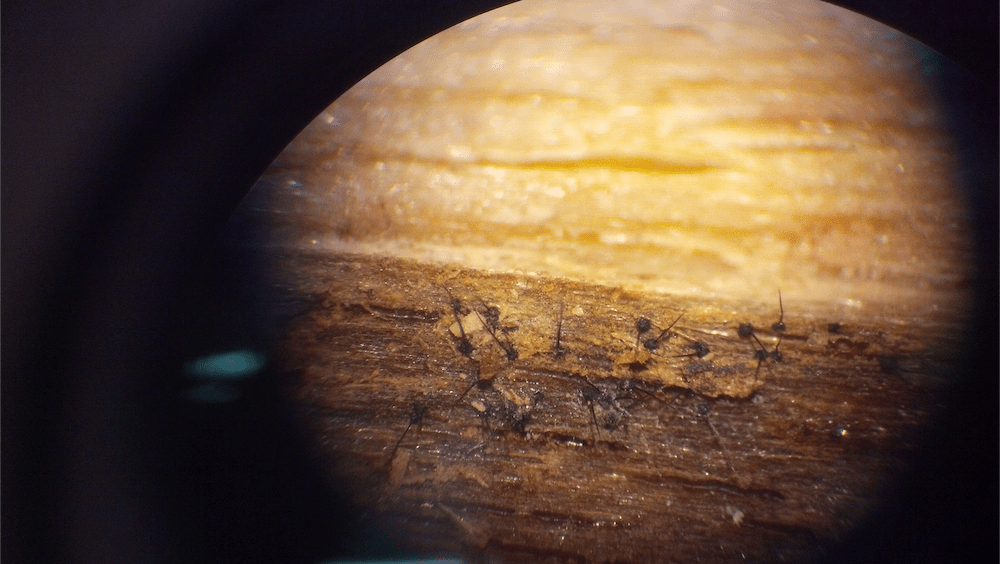

Once there is a wound, the fungal spores get in. They germinate and start to infect and then rapidly move throughout the tree. And what’s really tricky with this disease is there’s not a telltale sign. There’s not purple spots on the leaf that you can say, oh, that tree is diseased and has Ceratocystis.

We coined Rapid Ohi’a Death just by what we heard the public say a lot– that the trees were alive. They seemed to rapidly die, hence Rapid Ohi’a Death. We now know that there’s actually two specific diseases caused by these two species.

And that’s what’s so awesome about Greg’s work. The tree that dies rapidly– if you’re just looking from the outside, you see lots of brown leaves attached to a tree. Well, that also looks like, well, maybe the tree just didn’t get enough water and died because of a drought.

Now, if we can go into the sapwood of the tree, we’ll see the signs of the fungus with characteristic staining. But if you want to know before you actually get into the tree, that’s where Greg’s work is so awesome. Yeah. He can start to now tell the difference between was it drought or was it fungal attack.

IRA FLATOW: You can tell that from the air?

GREG ASNER: Yeah. The way to tell it is through its chemistry, just like going to the doctor and getting a blood test. It’s kind of that idea, except we’re flying over with instruments that can see into the chemistry of these trees and do it that way instead.

IRA FLATOW: If you’d like to ask a question, we have the mics open on the outside. Let’s go to this gentleman over here.

AUDIENCE: Hi. We had a family trip last year, an RV trip through the mainland. And we drove through Colorado. And we ran into a big block of trees suddenly that just seemed dead. And I had also heard that the Sierra Nevadas in California were facing a lot of sick trees and some things, too.

I’m just wondering, how common is it that we see these type of diseases that attack trees? As we see them, are they similar? Or are they totally dissimilar across these species?

LISA KEITH: Well, that’s a great question. There’s a lot of microbes in nature. And probably less than 1% actually cause disease. But when an invasive species like this fungus comes into a new area, and the tree and the pathogen has hasn’t coevolved, you tend to see very harsh effects like what we see here.

So 100-plus years, there have been major tree diseases, particularly on the mainland– Dutch elm disease and oak wilt. There’s mortality due to invasive insects. So it seems to be more and more common, actually, seeing major attacks of invasive pests and pathogens.

IRA FLATOW: You know, lot of times we hear stories about how, whether they’re insects, they’re bugs, they’re pathogens– have developed a tricky way of spreading so that they fool. Is this the case here? Has this fungus found a way to make it easier for it to spread somehow?

LISA KEITH: Well, the fungus itself is not airborne. So if you think of, say, a dandelion that gets caught up in the wind, this is not that type of fungus. So in order to spread, particularly from infected trees, if it’s entombed and it stays that way, the fungus won’t spread.

But once either boring beetles start getting into the tree, kicking out boring dust, or you happen to prune, now the fungus can actually start to spread, either in the wind, attached to fine material, or another big way. If you’re moving firewood from one area that has the infection to another area that doesn’t, that’s another way that it’s going to spread– or even if the fungal spores are found in soil. So they can hitch a ride on your cars or your boots and go from one area to the other.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Asner, speaking of spreading, are you going to increase your flyover of different places of Hawaii around the different islands?

GREG ASNER: Yeah. In 2016, we flew the big island. In 2017, we were asked to add the big island and windward Maui, the force of Maui. And coming up, we’re going to add Kauai, all the way out to Kauai. It is known that the pathogen has been found on Kauai now. So we’re trying to map not only where it might be, but the pattern of spread by remapping and adding more islands as we go.

IRA FLATOW: OK. Let’s go to this side. Yes.

AUDIENCE: Yeah, you were talking about it being an invasive species with these funguses that are coming in. I was wondering if you guys have figured anything out as to where it came from as a new disease or the path that it took to find its target in the ohi’a.

LISA KEITH: Well, there are a lot of Ceratocystis experts.

IRA FLATOW: There are what?

LISA KEITH: There are a lot of Ceratocystis experts, the genus. The fungus is called “Ceratocystis.” And we thought with this extensive genetic database that is available around the world that we could find precisely where it came from and how it got here.

But that hasn’t been the case because they are two new species. So we know the areas of the world where maybe their most genetically related cousins exist. But we’re still working on that million dollar question of where did it actually come from.

IRA FLATOW: Could it be going someplace from here? You know, I’m serious– on a boat or firewood, maybe, loaded on a boat.

LISA KEITH: Yeah, well, there’s definitely the quarantine in place that you can’t ship any kind of product off. Until just recently, it was contained on Hawaii island. We’re really trying to figure out the time frame for both species.

Were both of them more recently introduced? Or did we happen to find one because of the widespread mortality of the other? So hopefully there’s not going to be much more spread. But you’re right. It’s easy to hitch a ride on plant material or with travel, but hopefully not.

IRA FLATOW: Is it correct that you were the one who named these two new species?

LISA KEITH: Myself along with some help, particularly with Hawaiian practitioners and other scientists to try to give it an appropriate name. Yes. It’s common to name fungi after family members.

[LAUGHTER]

IRA FLATOW: Hmm. What signal does that send here?

LISA KEITH: And I do love my husband. And I thought, I’m not going to burden my daughter being known as something so harsh. So we really wanted to describe these two new species– Ceratocystis lukuohia, the destroyer of ohi’a, and Ceratocystis huliohia, the disruptor of ohi’a.

IRA FLATOW: Very dramatic. They deserve that name.

AUDIENCE: I sort of have two questions. One is, are you recommending– you alluded to it. Are you recommending that we not prune ohi’a trees?

LISA KEITH: If at all possible. If it’s not necessary, yes. It’s better not to even create a new wound.

AUDIENCE: Because that word has not gotten out. We know about no transport. Nobody has talked about “do not prune.” Where’s Flint? Is he here?

[LAUGHTER]

LISA KEITH: So actually, the recommendation is if you do prune, you can get just a simple wound sealant, which would temporarily prevent any fungal spores from getting in.

IRA FLATOW: Greg, what would happen if it was successful and wiped out all the ohi’a trees? What would happen to the rest of the– what would it do to the ecology here?

GREG ASNER: Ohi’a is what we call a “keystone tree species.” It generates the habitat for many other species. There are only a few native Hawaiian tree species that do that. And ohi’a is the absolute apex creator of habitat. So if we lose ohi’a, there’s a cascade of effects. And many other species all the way up to birds and the creatures that utilize that habitat are going to be affected.

IRA FLATOW: Is there a tipping point where you’ll know that it’s gone so far that you can’t save them anymore? Or are we near that yet? Or is it the percentage of trees still small enough?

GREG ASNER: We don’t know is the short answer.

IRA FLATOW: That’s a answer. A lot of times that’s the best answer.

GREG ASNER: Science is busy figuring it out today, so that’s where we stand.

IRA FLATOW: OK let’s go on to this side. Yes, sir.

AUDIENCE: The ohi’a tree is a culturally significant tree to the Hawaiian people. So it’s very important that it be preserved. But I have noticed– and I’m a volunteer here with the Kahilu Theater. And I have weed whacked the grass around here, including around the trunks of the seven or eight ohi’a trees that are here at the theater.

And two of them have died. And I almost feel responsible for having maybe weed whacked the bark of the tree and ultimately killed those two trees. So it’s a very sensitive issue for me. But I think homeowners and people that have ohi’a trees on their property probably need to be aware of how sensitive the trees are to these gardening devices which could kill them.

LISA KEITH: Yes. So actually, that is true, even having that happen without the presence of the fungus. Ohi’a is very, very strong and resilient and sensitive in a way at the same time. So it can only sustain a number of weed whacks or lawn mowing over roots, where it would die.

And just because there is a wound, if there is no fungal pathogen there, that’s the key. Yes, the fungus needs a wound. But it also needs the inoculation. So if it’s not present, it’s not going to get Rapid Ohi’a Death.

IRA FLATOW: Maybe we’ve eased his pain a little bit. I can see you’re very sensitive about that. I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. Greg, did you want to follow up on that? Do you have anything else you wanted to say? Because you wanted to jump in there.

GREG ASNER: Well, both from the scientific perspective and as citizens, we’re seeing that this wounding issue is a big one. And so we actually have to change our practices around ohi’a trees as best we can to protect them. As a homeowner here as well, we’ve seen deaths on our property as well just from our daily routine of mowing the lawn and so forth. So it is something that we have to adapt to and change along with that.

IRA FLATOW: Yes, sir.

AUDIENCE: Hi. How does the airplane instruments work? Because if you need to cut into the bark to identify that it’s not from drought, how can you do that from an aircraft?

GREG ASNER: Great question. I see you have a NASA sweatshirt on, too. I like that. We have unique technology onboard our plane that allows us to measure the chemical signatures of a tree. Just like you sign your name– the letters that make up your name as you sign it– we generally can tell that it’s you. We do that nowadays with trees using their chemical signatures.

And with this pathogen, it changes the chemical signature of the tree in such a way that it makes that tree stand out in our chemical mapping. And these types of instruments are not found in satellites today. They’re only found on certain aircraft. So it’s a new technology. It’s a new way of approaching these types of problems.

IRA FLATOW: Might it find its way into a satellite?

GREG ASNER: We’re working on it. I think if we’re lucky, we’re five years out. So we might be able to get this done everywhere not too long from now.

IRA FLATOW: Yes.

AUDIENCE: Hi. So I understand the significance of ohi’a as a keystone tree species in Hawaii especially. And I understand that there have been a lot of efforts to understand ROD, or Rapid Ohi’a Death, and how it’s spreading and the effects. But what advancements have been made in the prevention and– to be so bold– potential cure for this disease?

LISA KEITH: Well, the first big advancement was even figuring out the fungi killing the disease. We could then establish things like don’t move firewood or the proper sanitation protocols to help reduce the possible spread and also the quarantine.

I guess unfortunately, Ceratocystis diseases around the world– there typically is no cure. But that’s definitely the scientists’ high priority– to look for things which can prevent spread which could protect trees from being infected in the first place.

IRA FLATOW: So just dabbing the wound with something else is not going to stop killing the tree.

LISA KEITH: Correct. Yes. Unfortunately, as soon as the fungus gets into the tree, that’s the beginning of the end, unfortunately. And that’s not just our disease. That’s Ceratocystis diseases in trees.

IRA FLATOW: Is there any natural enemy a fungus has?

LISA KEITH: Some fungi, yes. There’s actually viruses that can attack fungi.

GREG ASNER: That’s it.

LISA KEITH: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: That’s it?

LISA KEITH: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, wow. OK. Over here.

AUDIENCE: So the instrument that you use– so to detect if the tree is healthy or not healthy, how many trees have you detected that were healthy? How many trees that you detected that weren’t healthy? And how many trees that you detected that were sick?

IRA FLATOW: This is going to be a scientist.

GREG ASNER: Send me your resume. That’s right. Great question. So as Lisa said, we think the fungus took hold in 2014 more or less. We didn’t start mapping until 2016. It took a few years for this thing to get to the level that said, OK, we need to make maps of what’s going on.

By then, we have this massive landscape, the big island, huge amount of forest cover. We have millions of ohi’a trees. We have a lot of dead trees already on the landscape that died because of drought. We’ve gone through some drought here in the last decade. We had all these other things going on.

So we had to map all of that first and kind of get the background understood. And then we were able to start finding the ones that are likely to be diseased. So once you get the background out, all the rest of the population accounted for, by 2017, we had about 43,000 trees that were expressing the symptoms that Lisa then goes in and tries to assess as the pathologist. So 43,000 trees in 2017.

We just flew a new mission for 2018. And I don’t have the results today to report a number. But we see that it has continued to spread, even in a quick look of the data. So it’s a big deal. It’s thousands of trees. But we have a lot of ohi’a trees out there. And that’s why I think both of us are pretty optimistic about some survivorship.

IRA FLATOW: Is it possible that some will survive because they have some natural immunity to the fungus, and they might take over?

LISA KEITH: Yes. And actually, that’s what we’re seeing in some seedling trials that we’ve been doing with known varieties inoculated the same way. You put the fungus in, and you wait and watch and see what happens. And typically, the ones that succumb to disease very rapidly– it could be within a month.

And there are seedlings now that are surviving a year and a half being inoculated the same way. So it really shows you that the host genetics definitely can play a role. And that’s why it looks a lot better now than when we first started.

IRA FLATOW: I can see why you’re optimistic. OK. Time for one more question. Yes.

AUDIENCE: I think you started to answer some of my question. What makes the ohi’a tree so susceptible to that particular fungi– and instead of trying to attack the fungi, to strengthen the variety of the ohi’a tree to resist that? That sounds like that’s what you’re doing.

LISA KEITH: Yeah. Unfortunately, we still don’t exactly know why it was so vulnerable. I think because it’s an invasive species that hadn’t been challenged the way it’s being challenged. So the disease is very harsh. But with these pathogens, unfortunately, even the most healthy tree, if inoculated, succumbs to the disease.

IRA FLATOW: I lied. I’m going to take another question.

AUDIENCE: OK. Thank you. I’m looking at this from a regenerative farming kind of perspective. And similar to the other question, what do you know about the soil health and how that affects the plant? Second part of the question, is it true that the ohi’a actually resists the vog and other fallout from the volcanic activity? Thank you.

LISA KEITH: The one-two punch.

IRA FLATOW: You know there’s a microphone right next to your mouth.

[LAUGHTER]

I just wanted to let you know about it.

LISA KEITH: So definitely, healthy soils, healthy plants. That’s the overarching answer with that. But again, unfortunately, if the fungus gets in, even in the areas of the most healthy soil, the healthiest plants, disease is–

IRA FLATOW: But you’ve raised a really interesting point. Me, being a very you know inquisitive guy, wants to know, could there be a relationship between the volcanic action and the fungus? Is it a coincidence that this is just happening in the last few years? Is there more volcanic action? Or is there some sort of something– you’re shaking your head no.

GREG ASNER: Nah.

IRA FLATOW: Nah.

[LAUGHTER]

That’s a good answer.

GREG ASNER: One thing that is interesting is, just anecdotally, scientists are seeing that areas that have elevated vog from the eruption from Kilauea– ohi’a is doing among the better survivors if they’re not getting burned by lava flow. Just from the gas itself, the ohi’a is one of the better survivors, along with a couple of other native species.

Some of the invasive species that are out there are not doing well in the vog. And we have some hypotheses as to why. But ohi’a does pretty well to a point. And then there’s so much vog in some areas that nothing survives. Those are pretty contained.

IRA FLATOW: Did you want to– you’re looking at– OK.

LISA KEITH: No, I definitely agree. I definitely agree.

IRA FLATOW: OK. I could not make a connection. Thank you both. This is fascinating. Thank you very much for taking the time to be with us. Greg Asner is an ecologist at the Carnegie Institution for Science in Palo Alto and here on the big island in Volcano. And Lisa Keith is a research plant pathologist at the USDA Agricultural Research Service in Hilo. Again, thank you both for taking time to be with us today.

[APPLAUSE]

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/