New Virus Paralyzes Chinese Cities

17:05 minutes

This story is part of Science Friday’s coverage on the novel coronavirus, the agent of the disease COVID-19. Listen to experts discuss the spread, outbreak response, and treatment.

A novel coronavirus—the type of virus that causes SARS, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), and common cold symptoms—has killed 18 people, and sickened more than 600. In response, Chinese officials have quarantined several huge cities, where some 20 million people live. In this segment, Ira talks with epidemiologists Saskia Popescu and Ian Lipkin about what we know about the virus, how it appears to spread, and whether efforts to contain it are effective—or ethical.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Saskia Popescu is an infectious disease epidemiologist and assistant professor at the University of Arizona College of Public Health and George Mason University based in Phoenix, Arizona.

Ian Lipkin is the director of the Center for Infection and Immunity and the John Snow Professor of Epidemiology at Columbia University in New York, New York.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. If you’re joining us via web screen today, I want to say thank you for taking time to come to us on a pretty big day for testing out– hoping you’re streaming– and listening to Science Friday.

A novel coronavirus– you’ve heard about this. The numbers just keep growing and not on the good side. It has killed at least two dozen or more people. And it has infected almost 1,000 people, including we now have at least two confirmed cases in the United States.

In China, the disease has now paralyzed a dozen cities with a combined population of 35 million people, as Chinese officials have grounded planes. They have cut off trains, buses, and ferries. Soldiers are reportedly guarding some stations. Tourist sites are shutting down, parts of the Great Wall and Shanghai Disneyland.

And at the disease epicenter in Wuhan, construction crews are furiously building a hospital they say will be ready for additional patients in just a week. We don’t know what that hospital is going to look like. And it will be steel walls or a big tent, we don’t know. But if it’s ready in a week, that will be helpful.

And from a scientific standpoint, this outbreak is very different from the SARS outbreak 17 years ago. Researchers have been encouraged by how quickly they’re getting genetic clues that tell us valuable information about the disease. We talked to one of them yesterday. Trevor Bedford, an evolutionary biologist at the Fred Hutchinson Research Center in the University of Washington.

TREVOR BEDFORD: So basically a week after registering that there’s a new thing, We via a kind of amazing scientist in China have a genome for this novel virus that has never been seen before. And then after the first genome was released on a Friday afternoon, we had five more on Sunday morning. And now nine days later, we’re up to 24, I think it is. And that first genome has been amazing for people developing rapid tests to be able to actually confirm cases. And the subsequent genomes are being very useful to understand the kind of basic epidemiological question.

IRA FLATOW: That’s evolutionary biologist Trevor Bedford talking to Science Friday yesterday. And now here to tell us more about the virus and the measures being taken to contain the outbreak are my guests. Saskia Popescu is a senior infection prevention epidemiologist at Honor Health in Phoenix and an infectious disease writer and researcher. Welcome to Science Friday, Dr. Popescu.

SASKIA POPESCU: Hi, thanks so much for having me.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. Ian Lipkin is director of the Center for Infection and Immunity at Columbia here in New York and the John Snow Professor of Epidemiology. He also assisted the World Health Organization and the People’s Republic of China during the 2003 SARS outbreak. Welcome back, Dr. Lipkin.

IAN LIPKIN: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: And we want to hear from you now that at least two cases have been identified here in the US. Are you concerned about the outbreak expanding? Tell us what’s on your mind. Our number, 844-724-8255. You can also tweet us @SciFri, S-C-I-F-R-I. Let me begin with you, Saskia. What’s the latest we know? Take us up to date about the outbreak.

SASKIA POPESCU: Well, in the United States that it was just confirmed we had a secondary case in Chicago is definitely concerning, and a rule-out case in Texas from what I’m hearing. So the last report the CDC gave was also there are about 63 people under investigation– or under concern, I should say, across, I believe, 22 states. 11 have been ruled out by testing, which is good.

So I think a lot of this really just comes down to really reinforcing preparedness within the front line health care and also public health. And that’s kind of what we’re working on right now. Because I think a lot of people get very concerned when they see airport screening measures. Now five airports are doing that with flights from Wuhan. And I think the biggest thing is reinforcing the knowledge and the skills we already have. We’re good at isolation. We’re good at screening. So we just need to kind of hone in on that.

IRA FLATOW: Well, so what’s the play here if they find somebody, Dr. Lipkin, if they find somebody who might be a candidate or might be ill? How do they know that, and what do they do with them?

IAN LIPKIN: Well, the signs and symptoms of this infection are no different than influenza or any of a number of other respiratory viruses. So the travel history at least now is key. If someone has been traveling near Wuhan province at this point, these are the individuals of whom we’re concerned. And we know the incubation period is typically two to five days, but it may be as much as 10 to 14. So those people who are returning from these areas, who have any sort of symptoms of respiratory illness, should report to a health care facility. And they should be treated as infected until we clear them.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Popescu, the World Health Organization has hesitated to declare the outbreak a public health emergency of international concern. I mean, if we’re worried about spreading around the world, why have they resisted doing this?

SASKIA POPESCU: I think there are a lot of factors. I mean, we’re still very early in this outbreak. We’re still learning about it. And you don’t necessarily want to jump the gun on a decision, but also the question about sustained human to human transmission has been really big. As of now, we’ve seen clusters. So we’re not seeing sustained human to human transmission. It’s more in families, health care settings, small groups.

And as this outbreak continues and we’re starting to kind of see from the new data that’s coming out, the new studies are saying, it might be changing. We might start to see sustained human to human transmission. If that happens, it will potentially change that declaration. I think a lot of it also comes into that this is not a global emergency yet. The declaration of a public health emergency of international concern is not one to be taken lightly.

And when we do that, it really brings in a lot of resources, a lot of efforts, which is wonderful. But we also have to really consider is this bubbling outside of borders? Is this truly impacting international health on that level outside of a couple of cases here and there?

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm. And Dr. Lipkin, tell us about this coronavirus. I know they come in many flavors. Is this a pretty innocuous one? Is it lethal? Where does this new strain fit in?

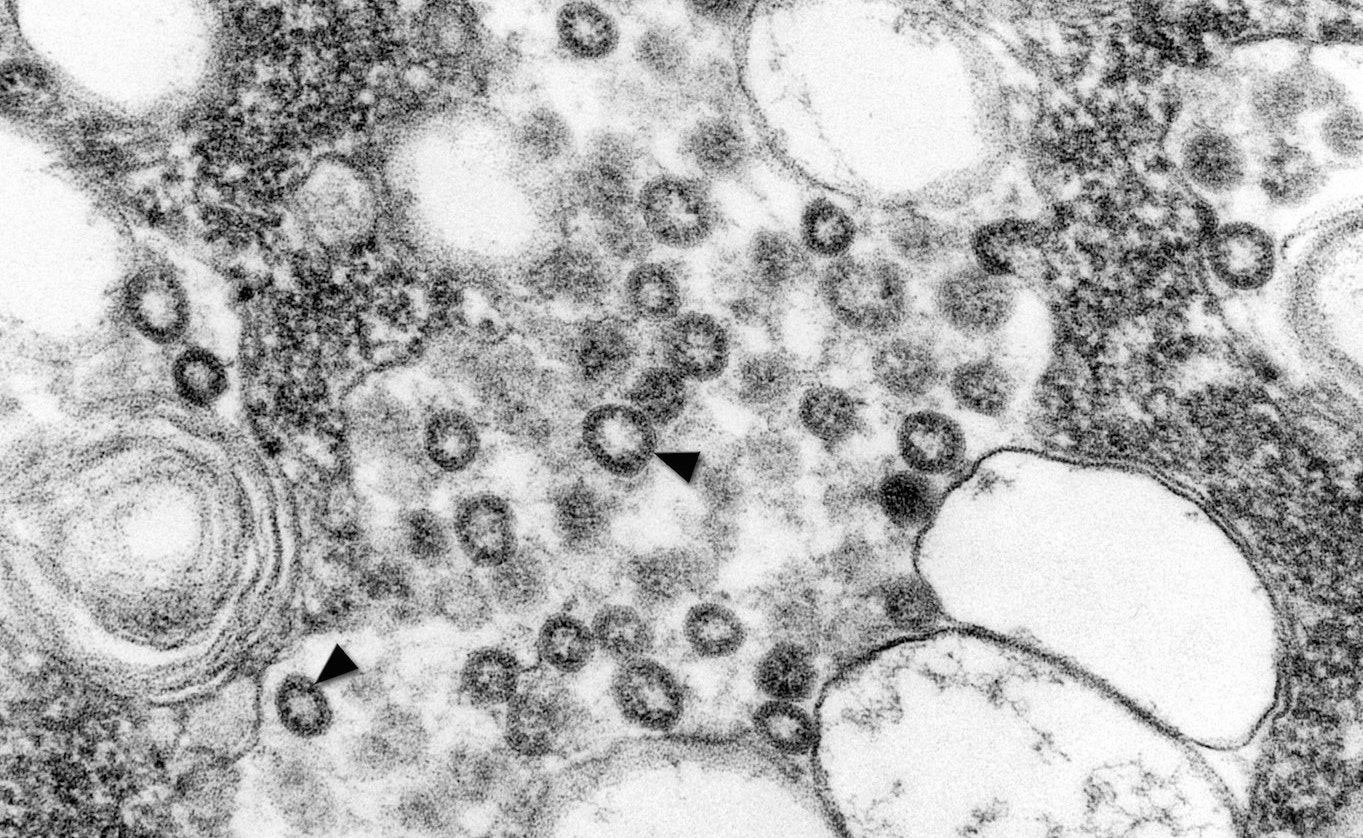

IAN LIPKIN: This particular virus is most similar to SARS coronavirus. It’s not identical. It’s 96% similar to a virus that’s been identified in a bat, which is a reservoir for many of these emerging coronaviruses. Its behavior thus far is more similar to the SARS coronavirus that we saw in 2003 and less than the MERS coronavirus.

I would not call it innocuous. Obviously, there’s a lot of disease already associated with it, and as you’ve heard, a minimum of 26 deaths. I personally believe that the outbreak is going to be much larger. And I would not be at all surprised if the WHO ranking doesn’t change. And this is being reviewed on a regular basis because as my colleague has suggested, it does require a lot of resources to change that designation. On the other hand, we need to move very quickly if we’re going to contain this virus.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s go to the phones. Our number, 844-724-8255. Kendall in Pensacola, Florida. Hi, Kendall.

KENDALL: Hi.

IRA FLATOW: Go ahead.

KENDALL: I have a– it’s a comment and a question. I was traveling around Africa right around the Ebola epidemic. And they were doing the same thing. They had body temperatures in the airports. And I actually came down with malaria when I was in Zambia. And I had to fly back to South Africa. So my friends and I put cooling blankets all over me to lower my body temperature right before I went into the scanner to make sure that my fever was low enough that I could fly. So if I was able to do that during the Ebola epidemic, what’s to say that people can’t do that now if you have the illness and they’re trying to come back to the United States, and they’re just cooling their body temperature down and then fly?

IRA FLATOW: Saskia, do you have a response?

SASKIA POPESCU: Well, first of all, I’m sorry that you were traveling with malaria. That’s a really good point. And part of it is that we know travel screening and airport screening isn’t perfect. It’s not designed to be a catch-all, especially during respiratory virus season, which we’re in. We’re in a heavy flu season. But it’s just one stopgap we can use, but also an education tactic. That’s the way I like to see it.

So even if you might be having a fever and you’re trying to cool yourself down, hopefully providing you with that information and that education should you continue to be sick will encourage you to seek care. That’s what we saw in Washington, actually, where before these airport screenings started to occur, the patient actually knew about the outbreak and sought medical care, knowing that they probably were exposed at some point.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm. Dr. Lipkin, there was a report out this week early. There was speculation suggesting this came from a snake, but that was quickly debunked by other scientists hopping on social media, trying to stamp out that speculation. And one of the reasons, the point I bring it up, one of the reasons they could debunk that is because there’s already so much genetic data available about this particular outbreak, why is that and how helpful is that?

IAN LIPKIN: So before we get into that, I just want to add one more thing with respect to the airport screening. People can be infected and not yet febrile. And there have been people who’ve become very sick without developing a fever. So as we’ve said, this is not as useful perhaps as identifying yourself as having been to a region where there might have been infection and being forthright about the fact that if you develop symptoms, you need to get evaluated.

Now the point of the snake, this is fascinating when this first came out, not so much because it was wrong and those of us who know a lot about these viruses recognize it as such, but because the community policed it so well. Immediately went back and said, this thing is 96% identical to other viruses that have been identified in bats. And it’s highly unlikely that this is something that represented a virus that came out of a snake. Though it made for a very, very good story and there are lots of interesting figures in that paper for those of you who want to look at it.

But it illustrates the point that today with social media and rapid sequencing, we can learn so much so quickly. In 2003, the genome of SARS coronavirus took a team of people working around the clock for over a week. With modern sequencing methods, we can generate these sorts of data in a matter of hours. So it’s social media and it’s also improvements in technology that allows us to get a handle on this so quickly.

IRA FLATOW: So how far away then– and I’ll ask both of you, and let me start with you, Dr. Popescu. How far away if you know so much about the genetics is a vaccine for this?

SASKIA POPESCU: Whew. I am not a virologist, so I applaud those that are working on them. I would imagine a couple of years, to be honest with you.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Lipkin, you agree?

IAN LIPKIN: No, I think it’s a much shorter time frame. I mean, first of all, to make a vaccine against this virus is not going to be that difficult. We know the protein that’s likely to be implicated in attaching to cells and getting into them. The challenge is always with the development, the manufacture, and the distribution. Because this requires different levels of testing, safety, as well as efficacy. And that’s what takes time. It wouldn’t surprise me if we didn’t have a vaccine candidate in a matter of weeks. But it may take as much as a year to roll it out. It shouldn’t take that long, and we’re continually trying to accelerate that process.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s go to the phones, get a call before we go to more questions. Suzanne in Dolores, Colorado. Did I get that right, Suzanne?

SUZANNE: Yes, you did. Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: Go ahead.

SUZANNE: Hi. In 2017, in Wuhan, China, a biosafety level 4 lab was opened to study new pathogenic viruses. And SARS was one of them. There’s an article in the February 17 issue of Nature Journal about this biosafety level 4 lab in China. And it expresses concerns about China’s ability to contain– excuse me– the pathogens in this lab. Can any of your experts weigh in on this?

IAN LIPKIN: I’d be happy to take that, Ira, if you wish.

IRA FLATOW: Go ahead.

IAN LIPKIN: So I’ve been to Wuhan, and I know the investigators who work in that laboratory. And they’re careful investigators. They’re world class. And I’m not concerned about an infraction that would lead to a release. More likely in my view is that there were wild animals in this market in Wuhan, not snakes, but small mammals and bats that transmitted this virus to people who went into this market. And then it ultimately shifted to a human to human transmission. We run into this concern, and I understand it because it seems like you might be concentrating on risk. But in fact, scientists who work in this area are inevitably very, very cautious and very, very concerned.

IRA FLATOW: Let me break in because I have to give a station break. I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. And I want to go to one last question before I run out of time for Saskia. You wrote about how the US just cut funding for the type of hospitals that deal with disease outbreaks of this nature– coronavirus, Ebola, stuff like that. Tell us what’s going on here.

SASKIA POPESCU: Well, after right about 2015, right after– or during, I should say– the Ebola outbreak, there was a tiered hospital approach to dealing with special pathogens. Now this new coronavirus has not been classified as that. So it is important to say that, but something like Ebola that really requires enhanced health care measures and that we’re just not prepared for. So we developed four tiers, and that includes frontline hospitals, which are the most– or the majority, I should say– assessment hospitals, treatment centers, and regional treatment centers.

And unfortunately, the funding for everything but those regional treatment centers– and there’s only about 10– is set to expire. So the concern is that in the face of a new outbreak, it’s always a good reminder of how prepared are we, how well are we supporting our preparedness efforts, especially on the front lines in health care. And with this kind of funding set to expire, it’s very concerning because it doesn’t necessarily encourage hospitals to maintain that increased level of readiness that we know is expensive. And you know if it’s not a very common event, there’s just not a lot of incentive there.

IRA FLATOW: And where did that funding come from?

SASKIA POPESCU: It was through the Health and Human Services, the health care emergency preparedness funding. So they did special Ebola funding just for this.

IRA FLATOW: And so it’s going to expire in a few weeks?

SASKIA POPESCU: Yes, I believe in March and April, it’s set to expire.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Lipkin, do you share her concern?

IAN LIPKIN: I do. Funding for research and public health preparedness is down. In some ways, we’re a victim of our own success. If we do our jobs well, people ignore us. But emerging infectious diseases are unfortunately here to stay. So it’s a marathon, not a sprint.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm, and so we need a larger, longer range picture of this then, is what you’re saying.

IAN LIPKIN: Yes, we need sustainable–

IRA FLATOW: And Doctor–

IAN LIPKIN: –support.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Dr. Popescu, what would you suggest happen?

SASKIA POPESCU: I would love to really focus not just on the top tier, which will likely to continue funding, but also the front line hospitals, because when people get sick, whether it’s from an emerging infectious disease or anything else, they’re going to go to a health care facility. And unfortunately, there’s just not the resources and attention to infectious disease and bio preparedness. So I would love more attention to that and more of that public private partnership.

IRA FLATOW: Unfortunately, it takes a disease outbreak like this one to get that attention, right? And then it goes away, as you were saying. I want to thank both of you for taking time to be with us today. And have a good weekend. Ian Lipkin, director of the Center for Infection and Immunity at Columbia here in New York and John Snow Professor of Epidemiology, and Saskia Popescu, senior infection protection prevention epidemiologist at Honor Health in Phoenix and an infectious disease writer and researcher.

Copyright © 2020 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christopher Intagliata was Science Friday’s senior producer. He once served as a prop in an optical illusion and speaks passable Ira Flatowese.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.