Complex Human Behaviors May Have Evolved In Our Earliest Ancestors

11:40 minutes

Scientists have been trying for a long time to piece together a question: When did traits of modern humans—like complex thinking and behaviors—first develop?

Our earliest human ancestors appeared around five to seven million years ago, and Homo sapiens, our species, came onto the scene around 200,000 years ago. Recently, anthropologist Alison Brooks and her team analyzed tools and soil samples from sites in Kenya that date to the Middle Stone Age, which began 280,000 years ago. They found that the tools at these sites contained non-local materials, indicating that early humans developed social networks and advanced technology tens of thousands of years earlier than previously thought.

[In a noted food lab, the glass may be half empty.]

Their results were published this week in three studies in the journal Science. Brooks joins guest host Flora Lichtman to explain what these findings mean for our understanding of human evolution—and how climate change may have helped to push these technological and behavioral innovations.

Alison Brooks is a research associate in the Human Origins Program and a professor of Anthropology at George Washington University in Washington, D.C..

FLORA LICHTMAN: This is Science Friday. I’m Flora Lichtman. Ira Flatow is away.

This week, at South by Southwest, Elon Musk said his BFR– his big rocket capable of reaching Mars– might be ready for testing early next year. Later in the hour, we’ll imagine what a Martian civilization might be like with some space futurists. But first, we’re talking about another technological revolution. It was a period when new ways of social networking were developing, and innovation was totally changing how folks lived.

And no, I’m not talking about Silicon Valley. I’m talking about the Middle Stone Age around 280,000 years ago.

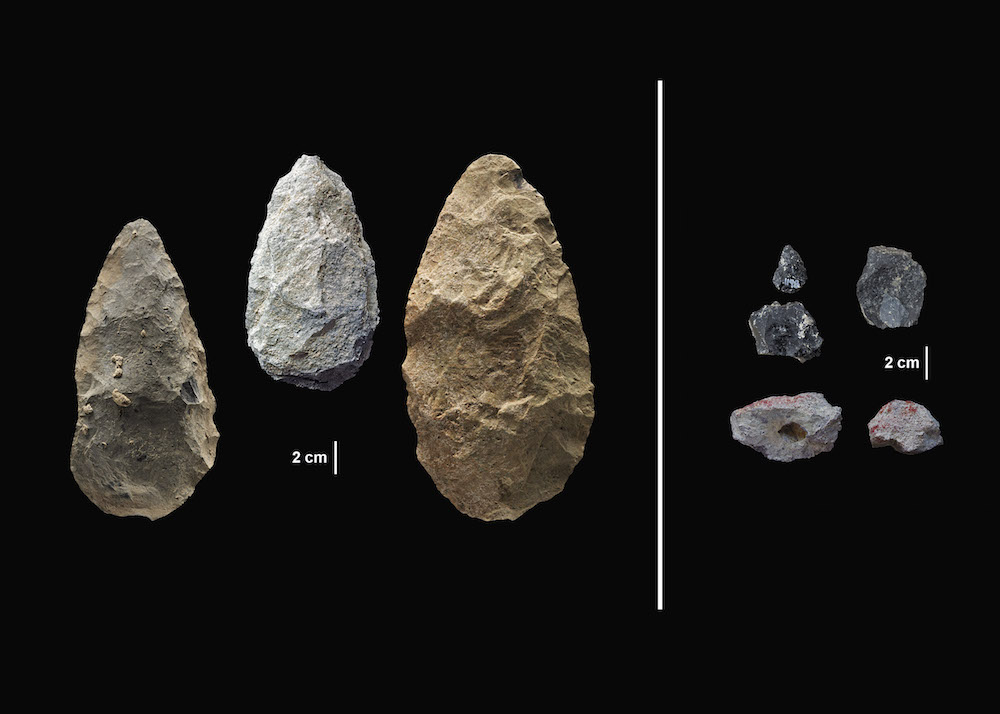

This week, researchers report in the journal Science that our early human ancestors were making advanced tools far earlier than we thought. Forget about that clunky hand axe. We are talking about tiny intricate spearheads. And these ancient humans may also have been trading with each other. This would push back the first evidence of trading by 100,000 years.

So what do these findings tell us about how we became the complicated humans that we are today? Here to talk about that is my next guest. Alison Brooks is the author on the study. She’s also a Professor of Anthropology at George Washington University. Welcome to the show.

ALISON BROOKS: Thank you.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Alison, tell me about these tools.

ALISON BROOKS: Well, they are very carefully made. They required a lot of planning to make them because you had to prepare the block of stone to get off a flake that was just the right thinness and the right shape so that you could then make that flake into a point or a scraper or whatever you wanted to make it into.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Yeah, what did they look like?

ALISON BROOKS: The tools– the points are triangular. And sometimes the tip is so sharp that we think maybe it was designed to make holes, rather than slice into animals. And they are made preferentially on a black stone that comes out of a volcano and cools.

It’s a volcanic material that cools so quickly. It doesn’t have time to form big crystals. And it is more like a glass.

So if you’ve ever broken a glass, you know how sharp the bits are. And this is the sharpest material that we know of Actually. And sometimes gets used in surgery today because it’s so sharp.

FLORA LICHTMAN: And how did this change our picture of the Middle Stone Age?

ALISON BROOKS: The thing is that we knew that 100,000, they were making points out of this material, and they were importing it from many directions and many sources. But this is 300 to 320,000, so it’s much older than that. We had a publication last year that showed that obsidian was this black glass. It’s called obsidian, that it was being imported from a distance in central Kenya that was even greater.

But this is 100,000 years before our finding. So the fact that we have these small points, the fact that the bases are trimmed so that they can be easily inserted into a haft, and the fact that they’re made of this material, which doesn’t occur in the vicinity of the site where we found them. And the fact that we were able to trace the sources of the material in the site and each level of the site to a lot of different sources in the surrounding region. So they weren’t just going to one source. They were going to a whole range of sources.

FLORA LICHTMAN: And in terms of the types of tools, can you give me an analogy for the kind of technology upgrade we’re talking about? When we’re talking about going from hand axes to these kind of pointy or smaller tools?

ALISON BROOKS: Well the technology– it’s much smaller, much more specific. The hand axe was a big tool that was more like a Swiss army knife that you could use in multiple ways, except it didn’t have a lot of different blades, obviously. You could use the long side of it for cutting up animals.

You could use the tip for gouging or picking at things. You could use the broad base of it for pounding things. And so it wasn’t a very delicate tool.

It couldn’t do anything very specific, and you probably couldn’t stab it into an animal. You might be able to throw it at something. Yep.

FLORA LICHTMAN: This sounds like flip phone to iPhone to me. Is that fair?

ALISON BROOKS: I would say it isn’t even a flip phone. It’s more like a princess phone or something from the stone age of telephones.

FLORA LICHTMAN: This obsidian– it wasn’t nearby. It didn’t exist nearby. Where did it come from?

ALISON BROOKS: Well, we have sources in the surrounding region. One of them is almost 100 kilometers, which is about 60 miles away. Others and their sources to the north, most of them are– let’s say 22 to 30 miles away. But the important thing is that these are straight line distances.

This is a landscape like some place in the Western United States that’s full of mountains and mesas and canyons. And you can’t walk anywhere in a straight line. So in fact, these are minimum distances if you could actually fly. These were long tracts for people that probably represent moving into places that were occupied by other people.

FLORA LICHTMAN: So the idea is that maybe these human ancestors traded these materials?

ALISON BROOKS: Well, I think that the idea of trade– I lived with foragers in the Kalahari Desert for many, many months over about 17 years. The problem with foragers is that they experience downtimes when the environment doesn’t provide enough food. There’s been a flood. There’s been a lack of rainfall. And what do they do?

They don’t have a bank, where they can put money. They don’t have a silo full of grain they don’t have a barn with cows in it they don’t have any way to save for a rainy day, except by building up obligations among their neighbors. So people who live in this sort of situation tend to create these relationships.

The most valuable thing you might get on a trip like this isn’t necessarily the obsidian. It might be the relationship with the people who live with the obsidian. And there they consider it a value to meet you because then if things go bad, you can’t move your whole group into that particular person’s territory because very soon, they wouldn’t have anything to eat. But you can move yourself and your children and your wife and so on to go and stay with that person because they’ll have some food that you could survive on. So it’s almost a way of saving for the future.

FLORA LICHTMAN: One thing that struck me as I was reading these studies was does this change our sense of the evolution of language? Like how do you trade with other groups or exchange goods with other groups of that language?

ALISON BROOKS: The thing that I find interesting is at the same time, we have some very early evidence of the use of pigment. And you think, how am I going to signal or show who I am before I can be close enough to actually take some of this obsidian? And we can imagine that people might be hostile to somebody just walking into their territory and taking some of their stone.

So it’s very interesting to me that we also have pigments in this time range. Of two of the sites we excavated, one had brown pigments. One had bright red pigments. And the bright red and this brown, often dry landscape, really shows up.

You can see it very far away– somebody coming with a red hat on or a red shirt. You really notice it.

FLORA LICHTMAN: But this seems like a huge change from how we have envisioned human evolution. I mean, I feel like we hear about these things happening much later, like 100,000 years ago, rather than 300,000 years ago.

ALISON BROOKS: We do. And I have thought for a long time that the roots of the things we see at 100,000 years ago were very ancient. And I’ve been trying to excavate sites in that time range that would shed light on exactly what was going on. So we were really quite amazed to find not only the points but also all this obsidian that doesn’t come from the local area. And I might mention that the pigments don’t come from the site either.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Wow, so is this changing the narrative in a pretty significant way then?

ALISON BROOKS: I think that it goes along. I mean, we’ve been pushing it back for a while. I wrote a paper with a colleague about 18 years ago that said we should push the idea that major aspects of our modern behavior– we should push that back to before 200,000. But this is now before 300,000.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Wow, why are people resistant to that idea?

ALISON BROOKS: Well, what people are struggling with is why did we then take over the world? And it looks as if the people who emerged out of Africa and took over the world may have taken it over that the genetics are telling us that they took it over 50,000 or 60,000 years ago. So there is a search for some tremendous change that took place 50,000 or 60,000 years ago, but we would argue that what happened is actually that maybe there were several excursions out of Africa that didn’t leave any descendants in us, which is given how long ago it was, is certainly possible. And the one that was successful may be successful because they had used the basic elements of what we’re now seeing at 320,000 years to develop even more complicated weaponry. Or even more complicated social relationships or something like that.

FLORA LICHTMAN: It’s so fascinating. I can’t wait to see what you find next. Alison Brooks is a professor of anthropology at George Washington University. Thanks for joining us today.

ALISON BROOKS: Thank you for having me.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.