How To Prepare Your Healthcare System For A New Coronavirus

22:20 minutes

This story is part of Science Friday’s coverage on the novel coronavirus, the agent of the disease COVID-19. Listen to experts discuss the spread, outbreak response, and treatment.

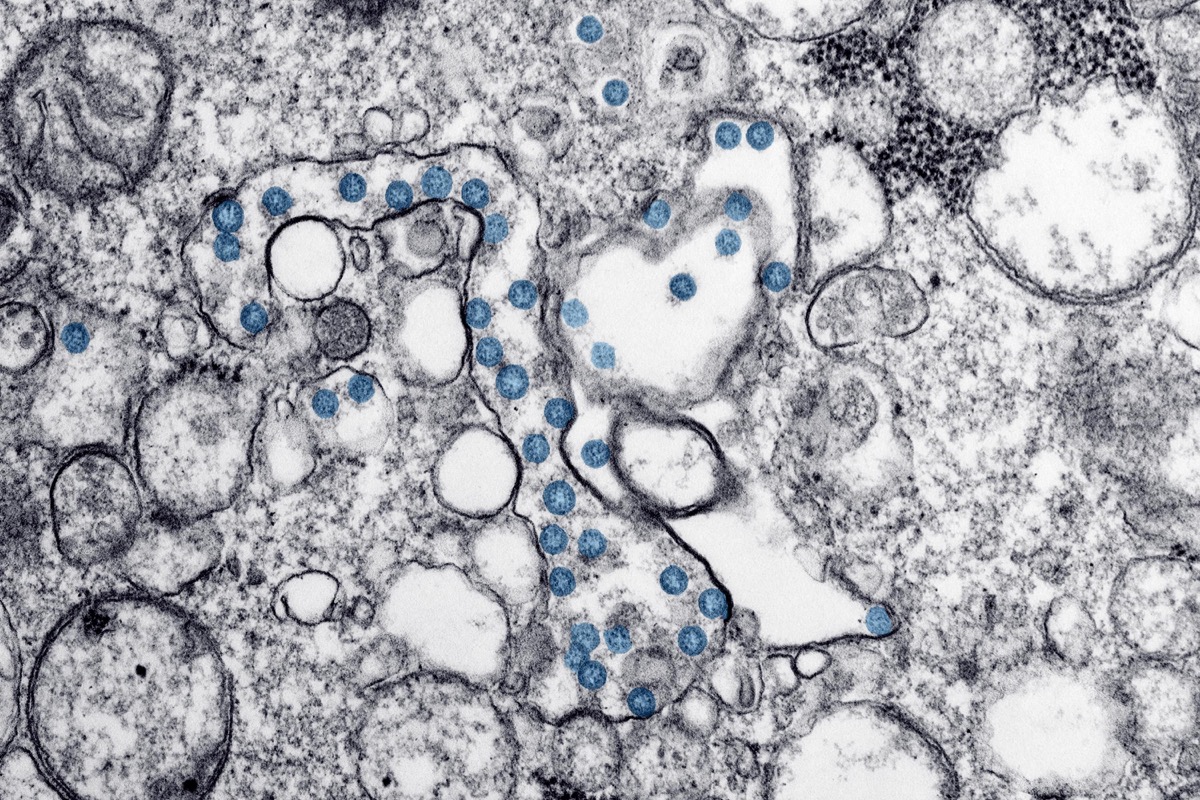

This week, the world’s attention has turned to the spread of the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, that was first detected in Wuhan, China, late in 2019. More countries are finding cases, and in the United States, a California patient has become the first known case of possible “community spread”—where the patient had not traveled to affected areas or had known exposure to someone who had been infected. On Tuesday, the Centers for Disease Control said Americans should prepare for “significant disruption” and “inevitable” spread of the virus in the U.S. And on Wednesday, President Trump announced that Vice President Mike Pence would head the country’s coronavirus response.

But what does preparation actually look like for healthcare systems that will be on the frontlines of detecting and responding to any new cases? Ira talks to infection prevention epidemiologist Saskia Popescu and public health expert Jennifer Nuzzo about the practical steps of preparing for a new pathogen, including expanding testing and making sure healthcare workers have necessary protective equipment. Plus, they address why childcare, telecommuting, and community planning may be more important than face masks for individuals who are worried about what they can do.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Saskia Popescu is an infectious disease epidemiologist and assistant professor at the University of Arizona College of Public Health and George Mason University based in Phoenix, Arizona.

Jennifer Nuzzo is an epidemiologist an the Inaugural Director of the Pandemic Center at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island.

IRA FLATOW: This is “Science Friday.” I’m Ira Flatow. It has been a big week in the life of the 2019 novel coronavirus, which causes the respiratory illness now known most simply as COVID-19. The number of countries where cases have been found is up to at least 54, that’s as of today, with more than 83,000 cases confirmed globally.

In the US, a California patient has tested positive. And this is the important part– no known chain of transmission, a sign of potential undetected spread in the community. And the CDC warned Tuesday that Americans should be ready for significant disruption of their routines as the virus spreads.

NANCY MESSONNIER: Ultimately, we expect we will see community spread in this country. It’s not so much a question of if this will happen anymore, but rather more of a question of exactly when this will happen and how many people in this country will have severe ailments. We will maintain, for as long as practical, a dual approach where we continue measures to contain this disease but also employ strategies to minimize the impact on our communities.

IRA FLATOW: That’s Nancy Messonnier, Director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. Then on Wednesday, the president appointed Vice President Mike Pence to head the efforts to combat coronavirus in the US.

And on Thursday, it was announced that government health officials must not speak to reporters on their own but now clear their comments to the media through the White House. Just today, the World Health Organization raised its global threat level to very high, their most extreme tier. Like I said, a big week.

But there is another story here, too, which is the practical, on the ground process of monitoring for further spread, responding to it. Hospitals and clinics, research labs, local health departments, even school systems all have parts to play. You know, we’ve seen this before with the H1N1 flu. And we’ll no doubt see it again.

Health care workers need protective gear and safety protocols. You need guidance on when to get tested and how, and whether you should stay home or go to an emergency room.

And all this talk of politics. What does that chain of command at the federal level actually do for our ability to protect people and communities? So we have a lot to talk about. We’re going to talk about these public health measures with my guest, Dr. Saskia Popescu, a senior infection prevention epidemiologist for Hope Health in Phoenix, Arizona. She’s also an infectious disease writer and researcher. Welcome back.

SASKIA POPESCU: Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. Dr. Jennifer Nuzzo, associate professor and senior scholar at Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore. Welcome, Dr. Nuzzo.

JENNIFER NUZZO: Thanks so much.

IRA FLATOW: And I wanted to ask our audience, if you’re a health care worker, and if you’re preparing for coronavirus in the United States, we’d like to hear from you. Give us a call about what it’s like on the ground. What are you seeing around you? Our number 844-724-8255. 844-SCI-TALK. As always, you can tweet us @scifri.

Dr. Nuzzo, first things first, let’s talk about this thing called community spread. What does it represent? Why is it such an important shift in the progress of the spread of the coronavirus?

JENNIFER NUZZO: Well, what we’re learning about this patient so far is that she did not travel to any of the places that have been reporting cases of the coronavirus and doesn’t seem to have any contacts with any known cases. So that leaves a bit of a mystery as to where she may have gotten her infection.

It’s an interesting shift because, typically, people in this category may not have been tested. So it also raises questions about how many more people like this patient are out there.

IRA FLATOW: Well, that raises an interest more questions, of course. And people have been asking me this a lot. And I’d like to ask you this. How do you identify a person? Let’s say this one, the woman in California who was infected. How do we know? How did she get into the system? Why wasn’t it thought about just that she had the flu or something like that?

JENNIFER NUZZO: Well, she had been hospitalized for quite some time before she had actually been tested but some astute clinicians thought that it was strongly possible that she had the coronavirus infection. Why exactly they thought that we didn’t know. My guess is that they ruled out other infections. But there may have been something about her, or her life or work, or something that also raised suspicions. But those details haven’t been reported.

But nonetheless, they essentially requested that she be tested regardless. And I’m really glad that they did because this is quite revealing. And I think it also speaks to the real value and roll that astute clinicians can play in terms of spotting some unusual situations and sort of being the first notice of it for us.

IRA FLATOW: Well, one of the key issues we want to talk about today is testing. And in this case, was she tested locally? Do local officials have tests or did they have to send her case over down to NIH for the final results?

JENNIFER NUZZO: So CDC is confirming all the tests now. That is supposed to change shortly. There had been some problems with the tests that were being sent out to the state laboratories. The CDC had developed a test and sent a test out to the laboratories.

And it’s required by the FDA that the states go through a test of the tests to make sure they’re functioning properly. And there had been some difficulties there. So they had to figure out why that was.

And my understanding is they’ve gotten some new materials to send out to the states and will be doing that. And then they’ll have to go through a retest to make sure they can do the results themselves. And we’re very much looking forward to that because it’ll be quite important to have additional testing partners in this.

IRA FLATOW: Saskia, on a press call today, the CDC’s Dr. Messonnier said that test kits are now on their way to state labs. And the CDC has some ambitious goals for making sure they’re widely available.

NANCY MESSONNIER: Throughout the day today, we expect additional states [INAUDIBLE] to be standing up. And we expect that to be happening for the next week. Our goal is to have every state and local health department online doing their own testing by the end of next week and doing everything we can to try to ensure that.

IRA FLATOW: And Saskia, how important is it that the states themselves have the test kits?

SASKIA POPESCU: I think this is vital, first and foremost, the definition for the patients under investigation for testing criteria expanded yesterday from the CDC, which means that we’re going to be testing more people. There will be more people that meet this definition. So we need to have the lab capacity to match that.

And realistically, we don’t want delays in sending a patient’s test and then having to wait multiple, multiple days because of that. So if we can bring it to the state and county level, that would be huge.

IRA FLATOW: Are the states trusting the CDC with the testing process? For example, New York state said just this week or even today that they were going to develop their own test.

SASKIA POPESCU: I have not heard any concern.

JENNIFER NUZZO: Sorry. I did actually look into that. It sounds like the question is not one of mistrust. I think the states who are looking to develop their own tests are looking for the flexibility that developing their own test affords. It allows them to purchase reagents from other sources.

So I don’t think it’s necessarily a reflection of lack of trust. I do know that they will be going through their own testing of the new kits that are being sent out by CDC. And if they don’t trust those results, then, of course, the tests won’t be done.

IRA FLATOW: So they’re sort of backing up the backup, coming up with the test of their own if they can’t get enough test kits.

JENNIFER NUZZO: Yeah. And this whole process is something that the FDA requires as part of the emergency use authorization, which is how this test– it’s a regulatory term that governs how tests are used in a public health emergency.

IRA FLATOW: Because I think, besides the testing, I think one of the issues that’s on everybody’s mind and was being asked at the very beginning is why don’t we have a vaccine. Right. Everybody wants to talk about getting a vaccine.

And Dr. Anthony Fauci of the NIAI Wednesday addressed the question, basically saying we can’t wait for one. Public health measures remain the best protection for people right now.

ANTHONY FAUCI: At the earliest, an efficacy trial would take an additional six to eight months. So although this is the fastest we have ever gone from a sequence of virus to a trial, it still would not be any applicable to the epidemic unless we’d really wait about a year to a year and a half.

Now that means two things. One, the answer to containing is public health measures. We can’t rely on a vaccine over the next several months to a year. However, if this virus, which we have every reason to believe it is quite conceivable that it will happen, will go beyond just a season and come back and recycle next year– if that’s the case, we hope to have a vaccine.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hm. Saskia, your day to day involves helping hospital workers prevent the spread of infections exactly like we’re talking about. Give us an idea of what the normal procedures are when a new potential infection enters this ecosystem. Let me give an example like the H1N1 in 2009 or even Ebola a few years back.

SASKIA POPESCU: Well, I think the first thing is really honing in on that admission and triage process, making sure those staff are aware and really fluid in their screening questions. Now that the definition has expanded, it’s not just focusing on travel but also wondering in our ICUs are those patients that we don’t have a reason for having a severe pneumonia, looking at them.

But we have to start with triage. And then we really need to focus on health care worker, PPE education reiteration. This is not a new form of isolation. We do airborne contact isolation every single day. But it’s about reiterating that with staff so that they feel comfortable in the process and they’re really just vigilant in their donning and doffing processes. But I think also now we’re really concerned about PPE shortages.

IRA FLATOW: PPE for us means what.

SASKIA POPESCU: I’m sorry. Personal protective equipment. So those masks, gown, and gloves. There has been an international concern with the shortages of the masks, specifically surgical, and then the N95s that health care workers wear.

So part of my process is not just to educate and make sure staff feel secure and informed in all of this but also what are our daily supplies looking like. How do we need to plan if we get a surge of patients? And that definitely takes up a lot of worry because you really need to engage your front line staff but also your hospital leadership.

IRA FLATOW: And so this has fallen to local state or local hospitals to do on their own.

SASKIA POPESCU: Yes. The CDC pushes out a lot of really helpful information. And then our county and state public health agencies do as well. But ultimately, it is up to the hospital to invest in those efforts and make sure they can adequately identify a patient, isolate them, and then inform the necessary parties.

IRA FLATOW: I want to get into those details. More of that when we come back after the break. Our number 844-724-8255. You can also tweet us @scifri.

We’ll get into the weeds on some of the details about the testing, about what hospitals need to do. Where do they get their money to do this? Is there enough federal money being allocated? There talking about that political football in Washington right now. Stay with us. We’ll be right back after this break.

This is “Science Friday.” I’m Ira Flatow. We’re talking this hour about how the US is preparing for the potential local spread of the novel coronavirus with my guests, Phoenix-based infection prevention epidemiologist Dr. Saskia Popescu, Johns Hopkins epidemiologist Dr. Jennifer Nuzzo.

And our number 844-724-8255. If you’re worried about what to do or you are someone on the front lines, one of the first responders right there in the emergency room, give us a call. 844-724-8255. And you can tweet us @scifri.

Dr. Popescu, we were talking about your day to day involvement with helping hospitals prevent the spread of infections. And you were talking about now the battle is being waged by local health departments, the hospitals and the clinics.

Are they ready for this? What else do they need? You mentioned some kinds of shortages. How do they make up for those things?

SASKIA POPESCU: I think anytime we have changes on testing criteria, that means we have to shift and adapt. So it’s a constant moving target of staying ready. But it’s especially difficult when there are shortages of masks that are necessary for health care workers not only because it’s respiratory virus season but also if we have patients with the novel coronavirus. And that’s particularly difficult because a lot of infection prevention efforts focus solely on hospitals.

But we also have a lot of urgent cares and outpatient clinics we need to consider. So it’s quite a task making sure all of the front line health care workers feel comfortable in these measures, how to identify and isolate a patient, but also, realistically, how are we planning for surges in the future.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm. Jennifer, I mentioned the federal response earlier. This week, there’s been a lot of movement, a lot of moving parts here. The president has put Vice President Pence in charge of the response. He’s requesting $2.5 billion. And all the communications about coronavirus must now be cleared by the White House. How do these political moves at the top trickle down to actual care and containment?

JENNIFER NUZZO: There’s a few ways. First, talking about the resources, I think that’s probably one of the most important. As Saskia has been describing, there is a lot of activities that need to go on at the state and local level. They’re on the front lines of this.

Our health care facilities are just part of that but there’s also the health departments that are doing all sorts of things about planning, planning for what measures we’ll use to try to slow down the spread of the virus, being the interface between the laboratories and the health care facilities.

So there’s a lot of work that needs to be done. And that work is above and beyond all the day to day work that these practitioners have to do. And so that’s where we get into a situation where we need to talk about additional resources to support them in that. So I think that’s going to be an important place.

The other areas where the federal response is important is, first of all, in setting the tone and describing what should come. And so that we’ve seen a shift in the messaging, particularly from the CDC, about what to expect has been very important.

Talking about this event as something that we should expect to see, prepare ourselves for there to be additional cases across the country, that’s really essential because that sets a signal to the state and local health departments and hospitals who have day to day worries that they have to deal with.

But hearing from the federal government that this is coming and this is a priority, that’s very essential, I think. Sending the alternative message of don’t worry, we’ll keep this virus out of our country, I think really undermines our preparedness. So I’m very heartened to hear that health authorities at the national level are speaking in realistic terms.

In terms of the presidential movement and appointing Vice President Pence to oversee this. First of all, I think it’s really essential that there be leadership in the White House on this issue. So for that reason, I think it’s important to have somebody named who’s above the federal agencies who can coordinate the work of the federal agencies and adjudicate any disagreements that come up to be able to move money and make requests of Congress for money. That’s very important.

But I think going so far as to require that all inquiries or messages be cleared from the White House, I think that’s probably an overcorrection. And I think that’s going to hurt the federal response in the long run.

IRA FLATOW: At a press conference on Wednesday, Dr. Nuzzo, the president held up a report from your institute, Johns Hopkins, that said proved that the US was the best prepared country in the world for a global pandemic. And I think that’s the big question. A lot of people are asking, are we ready? Is that report the evidence we need?

JENNIFER NUZZO: Well, as one of the senior authors of that report, it was a bit of a surprise that the president held it up. But that’s the global health security index which we produced in collaboration with the Nuclear Threat Initiative, which is an organization in Washington, DC, and the Economist Intelligence Unit, which is a research arm of The Economist magazine. But they are experts in indices. And what we found was that no country was fully prepared for a pandemic. Yes, the United States does well compared to others. But there are still places where we need to improve our preparedness.

And I think some of the issues we’re seeing now, some of the things we talked about with the health facilities and the lack of readiness there, and concerns and, in particular, some of the issues that we’re having, it just speaks to the fact that even places like the United States will have struggles in a pandemic.

IRA FLATOW: We’re starting to get a lot of tweets in. I’ll try to compress them because they’re asking what do I do as a person. They go with a range from how do I take the tests, and my loved ones are immunosuppressed because they have kidney transplants, things like this.

So let me just throw it out in general. We’re at a point in the story where people are really starting to ask what they can and should do as individuals. You know, it sounds like the story is wash your hands, don’t touch your face, make plans for the possibility of not being able to go to the grocery store for a week or two, to have your kid’s school closed.

Is there anything else you want us to know about our own role in protecting our communities, Saskia? I mean, first thing they’re doing is putting on these masks. And now we’re hearing that the masks probably, the kind we see people wearing, don’t offer any real protection.

SASKIA POPESCU: No. You really don’t want to be wearing a surgical mask unless you’re sick. And that’s a way for you to protect people around you. People that are buying up a bunch of masks, that’s only adding to the shortages. And I think it kind of gives this sense of security that leads to a lot of other infection control failures. I see people wearing masks when they don’t need to. But then they’re touching their eyes. They’re not washing their hands.

So it’s those tried and true flu season prevention strategies people need to be engaging in. But the problem is because this is a novel situation, people want a novel approach. And unfortunately, that’s just not the case. That hand hygiene, staying home when you’re sick, covering your cough, things like that, that’s what’s going to make a difference.

IRA FLATOW: What about we talk about tests. You know, why not have a test that everybody can take it home so you don’t have to go out and get infected or infect someone else? How close are we to that, Jennifer?

JENNIFER NUZZO: We don’t have a test at home we’re still trying to get the test to the public health laboratories. And I think this need to understand who has the infection and who doesn’t is an important one. I think in particular for doctors and nurses who are seeing patients, and treating patients, and know how to deal with them, that will be essential.

I think the idea of doing a test at home will be some time. And I think the main thing that I want to stress to people is that we would be in a bad situation were additional cases to occur in this country if people just kind of flocked to health facilities just wanting to be tested absent any kind of symptoms.

First of all, that would put a stress on health facilities because they just wouldn’t be able to handle that kind of volume of people coming. But also, we don’t typically test people absent symptoms. So the best thing that you can really do is that if you are sick, you should absolutely stay home and don’t go out and infect other people.

If you get to the point where your symptoms worsen, maybe your cold symptoms get to the point where you feel like you’re short of breath, contact your health care provider and find out what’s the best way you can access care in a manner that’s safe. We don’t want people just kind of showing up unannounced. If they can get directed by their health care provider, that would be helpful.

But otherwise, do the things that you need to do like wash hands. I agree it may sound overly simple but it’s probably the best evidence we have right now for how to protect yourself.

IRA FLATOW: And people don’t even know how to wash their hands correctly, do they?

SASKIA POPESCU: No. If my children are a guide, then the answer to that is very much yes. I mean I think the hard part is that everybody thinks hand hygiene is so simple. But then my response is, well, then do it.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. I do the “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star” method.

SASKIA POPESCU: 20 seconds. Whether that is making a grocery list or singing a song in your head, as long as you’re using soap and water for 20 seconds, I’m happy.

IRA FLATOW: And it’s not just you’re turning the water on, rubbing your fingers under the water, and then pulling it out. You have to really wash your hands for a full 20 seconds. And there are a lot of YouTube videos on how to do that.

OK. We have run out of time. So many questions, so little time. I want to thank both of you for taking time to be with us today.

SASKIA POPESCU: Thanks so much.

JENNIFER NUZZO: Thanks so much.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Saskia Popescu, senior infection prevention epidemiologist for Hope Health in Phoenix. Also an infectious disease writer and researcher. Dr. Jennifer Nuzzo, associate professor and senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore.

And now on our Science Friday VoxPop app, we’re going to continue to cover the global spread of the novel coronavirus in coming weeks. So we have a question for you. It’s a question of a question. What questions do you still have about this infectious disease? What questions do you still have about this infectious disease?

Go to our Science Friday VoxPop app. Download it, and get it, and answer that question. You might find your answer or your question on the radio.

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.