An Abrupt Departure For Biden’s Science Adviser

11:58 minutes

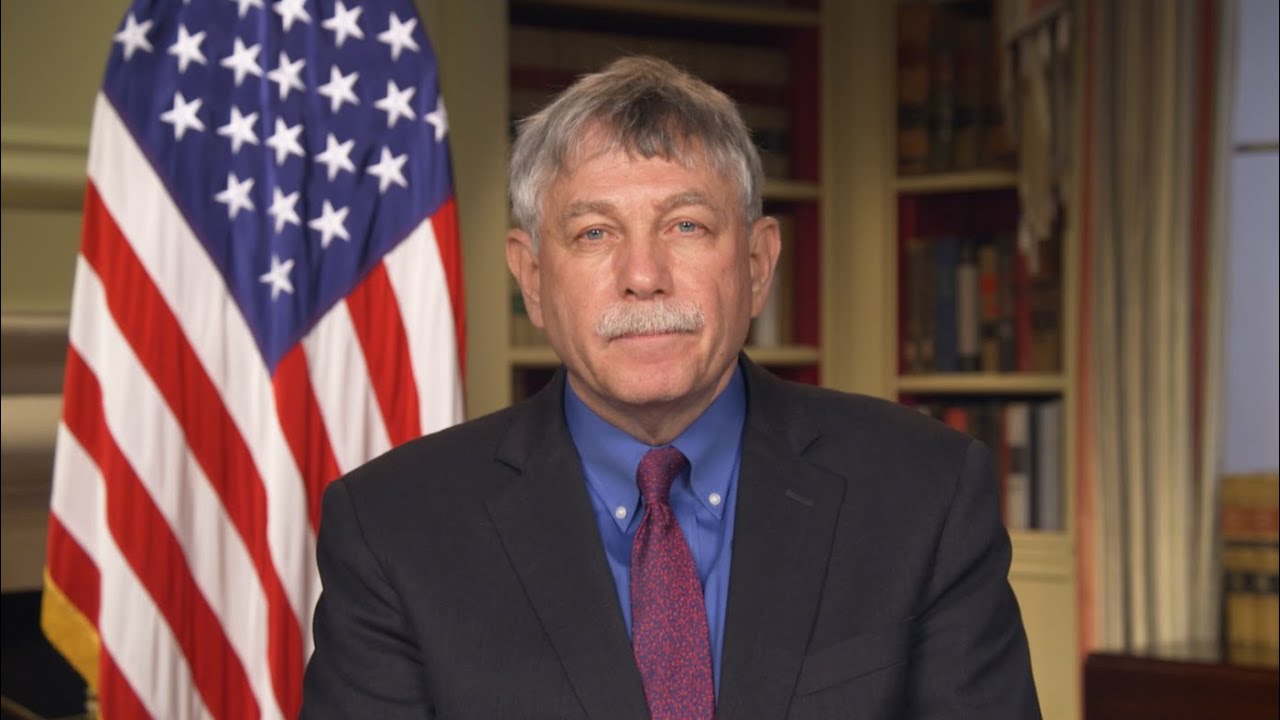

This week, Eric Lander, the Presidential science advisor and head of the Office of Science and Technology Policy, resigned following an investigation into bullying behavior towards his subordinates. In an apology, Lander acknowledged being “disrespectful and demeaning” towards staff.

Lander, a mathematician and genomics researcher, was previously the head of the Broad Institute at Harvard and MIT. Nsikan Akpan, health and science editor for WNYC Radio in New York, joins Ira to discuss the resignation and what it might mean for the president’s science policy initiatives.

They also talk about other stories from the week in science, including an advance in fusion research in Europe, concerns over the increasing saltiness of Lake Michigan, and the question of whether sequestering urine from the sewage stream might have environmental advantages.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Nsikan Akpan is Health and Science Editor for WNYC in New York, New York.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Later in the hour, we’ll talk about the tricky task of developing antiviral treatments for COVID-19, and we’ll meet the drag queens popularizing STEM.

But first, news this week that the world’s largest fusion reactor, called JET, near Oxford in the UK, smashed the record for producing controlled nuclear fusion energy by some 2 and 1/2 times. And while it only amounted to about five seconds of fusion and not a whole lot of total energy, it is notable for being a sustained, highest-powered controlled reaction for the longest time on record. We’ll have more on this landmark in the weeks to come.

There were so many other news stories this week. And joining me now to talk about the week in science is Nsikan Akpan, health and science editor for WNYC Radio here in New York. Welcome back, Nsikan.

NSIKAN AKPAN: Hi, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Nice to have you. Let’s talk about something unusual. This week, the White House science advisor, Eric Lander, resigned. Tell us about that.

NSIKAN AKPAN: Yeah, it’s interesting. You know, this story kind of started last week. My introduction to it was in a chat group that I have with a bunch of other scientists where we kind of just shoot the breeze about topics. And so somebody popped in and said, hey, had you seen Eric Lander’s apology in Politico? All of us sort of sat up in our chairs, because Eric Lander is a big shot in genetics.

He ran the Human Genome Project. You know, he’s a founder of the Broad Institute, which is part of MIT and Harvard in Boston. And then he was appointed Biden’s director of the Office of Science and Technology Policy last year. And Biden even gave him the extra honor of joining the White House cabinet.

So when that initial story broke last Friday, there was this apology, but it was all kind of clouded in mystery, like we didn’t know why he was apologizing. But given the current moment that we’re in, we could guess that it was probably harassment or bullying. So no one was particularly surprised when the full story came out saying that he had bullied and harassed his counsel. And it just sort of created like a toxic environment in general in the office.

IRA FLATOW: Do we have any speculation about how much this will alter President Biden’s science policy goals?

NSIKAN AKPAN: It’s hard to say. You know, Lander’s office was in charge of the Cancer Moonshot, which was a big agenda item for Biden. It actually predated his days as president as something that he really wanted to do. I think the indication right now– there’s a really good story in Science magazine that came out this week– the indication right now is that that will probably be fine. There was also a biomedical pipeline for funds to prop up advances and really instill support for our biomedical infrastructure. It’s looking like that’ll probably be fine, too.

I mean, I think Biden’s science agenda in general is a little wobbly. You know, he’s having trouble getting through his nomination for an FDA commissioner. And there’s obviously the issues around the Build Back Better bill and what it could do for climate change infrastructure.

IRA FLATOW: Whenever something like this happens, there’s always a speculation about who might be the next for this role. Any names floating around, rumors?

NSIKAN AKPAN: I think people have talked about Alondra Nelson, who had served with the Biden administration for a little while last year. I think the other thing that people are talking about is what this means in general for really big egos in science. So Matthew Herper of Stat News had a really great piece about that, and just wondering how far this reckoning is going to extend and how it could be potentially a good moment for science. I think if you go to any lab, any department, around the country, you’re going to have these sort of toxic personalities that people just kind of let slide by for years and decades. And it seems like everyone’s fed up, like there’s just no room for it anymore.

IRA FLATOW: That’s really interesting. We’ll watch for that. In other news this week, you pointed out a story about information and storing energy. Tell us about that.

NSIKAN AKPAN: Yeah, Tim De Chant at Ars Technica had this interesting story about a paper showing that information could be used as a battery. So he doesn’t mean like a literal battery. It’s not like something that you could stick into your computer or your phone. But it’s more of the idea that the data servers that we use consume huge amounts of energy, but there are also a lot of computations, a lot of processes, that we just do on a regular basis, almost at the exact same time every single day.

And so what this paper was saying is like, oh OK, what if we just siphoned off some energy for doing those routine processes that we know are going to happen at a precise time– so for instance, say every morning you wake up, you pull up Google Maps to find the best route to get to work. That process is probably made up of hundreds, if not thousands, of individual little commuted commands, right? Like, the map pops up, the little lines showing the bike lanes pop up. So let’s just store energy for that, maybe even use renewable energy for that, and then by doing that, you could actually save– I think it was about 30% of the energy waste that kind of goes to data servers.

IRA FLATOW: So things you do over and over again, we could save energy by knowing it’s going to happen over and over again.

NSIKAN AKPAN: Yeah, exactly. And Tim pointed out that, in our smartphones, we have little CPUs that are actually making similar decisions about how to preserve energy and when to do certain computations. So this would just be on a larger scale.

IRA FLATOW: Interesting. Snow is still on the minds of many parts of the country. And you have selected a story that’s really important about this time of the year. That’s road salt and runoff.

NSIKAN AKPAN: Yeah, you know, I think we just got hit by a snow storm, and I kind of just feel like every– around this time of year, I look out at the street, I’m like, oh, the roads have turned white, you know? What’s happened? And it’s just because, yeah, we put–

IRA FLATOW: It’s not the snow. It’s the salt sometimes, right?

NSIKAN AKPAN: Yeah, exactly. And then after that, I’m like, well, it’s going to wash away. Where is it washing to? Is that bad for the environment? So Robin Donovan at Eos found this really interesting paper looking at about 200 years of records of the salt levels in Lake Michigan and showing that they’ve risen tremendously over time, so from about 1 to 2 milligrams per liter to more than 15 milligrams per liter.

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

NSIKAN AKPAN: It’s a lot. It’s a huge amount.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah.

NSIKAN AKPAN: And how this study did it was they kind of looked at tributaries around Lake Michigan. So they went over to 300 tributaries, and they were able to figure out that, yeah, road salt is a major contributor to what’s going on. And they expect that it’s going to get worse and worse as the years go by.

IRA FLATOW: So they’re worried about a rise in salinity, then, of the lake?

NSIKAN AKPAN: Yeah, exactly. It’s like the salinity, the salt levels, can be a little bit worrisome for the environment. You know, our bodies, and most organisms, they like a very particular range of salt. So one issue that has been pointed out is the danger to zooplankton, or very small organisms. And if you knock those out, then you’re going to have issues with the food chain. Other studies, and there’s a really good story about this in Chemical and Engineering News from 2019 that showed that, oh, yeah, salt levels can actually really impact certain insects, which a lot of fish in these freshwater bodies depend on for food. So our road salt, just because you sort of sprinkle it on the steps and walk away, it can have sort of a chain reaction that can go throughout the environment.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s turn to a different kind of saltwater, and I’m talking about urine recycling and reclamation.

NSIKAN AKPAN: Yeah, this is an interesting story that came out this week in Nature. It’s a feature by Chelsea Wald. And I think it struck me because I’ve been reading Dune. In Dune, they have the–

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, where they recycle all the urine in Dune, right?

NSIKAN AKPAN: Yeah, exactly, have these suits that absorb their water content. And so this feature essentially talks about how there’s an international effort involving a lot of different labs to figure out ways to install toilets in all types of settings, so like apartment buildings, like stadiums, that will reclaim your urine rather than letting it flow into the general waste system with everything else that goes into the toilet. And from that, what you could do is you could start to isolate some of the chemicals that are in urine, like phosphorus, and then maybe you could use that for fertilizer for plants.

IRA FLATOW: It seems like that would take a fair amount of infrastructure change, would it not? Changing all those toilets to make them special.

NSIKAN AKPAN: Yeah, I mean, and that’s the thing. You know, there could be a really big payoff in that certain estimates say that there’s probably enough urine to replace about one quarter of the current nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers that we use worldwide. But it would be a huge investment, right? And there are some projects that are mentioned in this story that are trying to figure out ways to scale it up.

IRA FLATOW: And you know, there might also be some unintended consequences in that when we take drugs, right, we excrete them into our urine. So you’re going to be having a whole bunch of recycled drugs that might be put into the soil and wherever.

NSIKAN AKPAN: Yeah, it kind of depends. I mean, I think there are a few different ways to kind of collect and process the urine. One way is to just take it and put it in a storage tank and then take it from that storage tank and just spray it on your crops. But another way to do it would be similar to running it through like a water treatment facility. And I think if you did that, there probably are chemical processes that you could use to just isolate the fertilizer components and hopefully take out all of the medicines that we pee out on a regular basis.

IRA FLATOW: Finally, we all think about Chernobyl as one of the big environmental disasters of the modern age, right? But there’s new work coming out about its effects on wildlife, and it’s sort of good news?

NSIKAN AKPAN: Yeah, you know, I’ll just point people to this story, because it’s really long and super interesting. It’s in Knowable Magazine, and it’s by a science writer that I really like, Katarina Zimmer. And essentially, what she’s looking at is this debate that’s getting more intense about whether or not Chernobyl was completely devastating to wildlife in the area, or whether or not wildlife is resistant enough to sort of fight off the radiation that spilled out there.

It kind of speaks to a topic that I’m interested in, the replication crisis, this idea that some studies that we published many, many years ago, oh, maybe the methods weren’t that great, maybe the measurements weren’t that great, and now we’re kind of finding the opposite. And the reason I like those types of stories is because science is a process, right? No one study can really prove anything. And so I enjoy sort of seeing these debates and people trying to learn what exactly is happening in the world, which is why we do science.

IRA FLATOW: And we enjoy having you on, Nsikan.

NSIKAN AKPAN: Oh my goodness, I’m blushing. Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: Thanks for coming up early. Nsikan Akpan, health and science editor for WNYC Radio here in New York. We’re going to take a break, and when we come back, a closer look at the antiviral drugs of COVID patients. Stay with us. We’ll be right back after this short break.

This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.